The Untold Truth Of The Yorkshire Ripper

When it comes to notorious serial killers, there's probably none higher on the list than Jack the Ripper. He terrorized the streets of London in 1888, and while we don't know his real name, we know his eerie moniker. But how about the Yorkshire Ripper?

For him, we'll have to jump forward a bit in time, to the so-called "golden age" of serial killers. According to Psychology Today, that's the time between 1950 and 2000, when many children were raised in homes broken — or at least damaged — by World War II, exposed to the brutalization and sexualization of women in countless cheap drug store magazines and struggling to deal with their urges without psychological help.

The first victim credited to the Yorkshire Ripper was found in July 1975, and in the years following, the idea that a serial killer was stalking the Yorkshire counties in northern England terrified residents. But unlike Jack the Ripper ... now, we know exactly who was doing the killing.

The first victim of the Yorkshire Ripper

Every serial killer has their first victim, and on July 4, 1975, there was no way for Anna Rogulskyj to know that she wasn't just going out for the night — she was going out for a night that was going to change her life.

According to the Irish Independent, the woman known as "Irish Annie" was having a bad month: Her partner had moved out, and, worse, it appeared he'd taken her kitten with him. It was late at night when she left her home and headed for her partner's home in order to reclaim her cat, but she never made it. She turned onto North Queen Street when she heard a man proposition her from a dark doorway. She shot back with a wholehearted "Not on your life!" and kept walking, but the man continued to follow her.

At a little after 2:00 AM, she was found by a local youth who was taking a shortcut through the alley. She was unconscious, her skull had been fractured, and a 12-hour surgical procedure was required to remove shards of bone from her brain. Anna was given last rites, but, miraculously, she survived. She was unable to remember anything about the attack or the man who had stalked her, and the only description from witnesses was that it had been a man about 5'8" tall in his twenties or thirties. The investigation went nowhere ... until he attacked again.

The other victims of the Yorkshire Ripper

Over the next six years, the man who came to be known as the Yorkshire Ripper attacked again and again, and here's the first of many tragic footnotes to the case: The Guardian says that police investigators became convinced that the killer was on a personal crusade against local sex workers, and that led to the victims being labeled — at the very least — of "doubtful moral character."

But not all the victims fit that profile. There was Olive Smelt next, a mother of two who had been out for drinks with friends. There was 14-year-old Tracy Browne, a student and the Ripper's youngest victim. Then, Wilma McCann. Her body was dumped not far from her home, and police found not only her but two of her daughters, waiting for their mother at a nearby bus stop.

Emily Jackson, says Crime+Investigation UK, serviced her clients in the back of her company's roofing van in an attempt to make enough money to save the family house. She was stabbed more than 50 times with a screwdriver. Marcella Claxton, Irene Richardson, and Patricia Atkinson were also sex workers, but then the Ripper attacked Jayne MacDonald, a 16-year-old shop assistant.

The other victims? Maureen Long, Jean Jordan, Marilyn Moore, Yvonne Pearson, Helen Rytka, Vera Millward, Josephine Walker, Barbara Leach, Marguerite Walls, Upadhya Bandara, Theresa Sykes, Jacqueline Hill, and Olivia Reivers. By the time he targeted Reivers, it was January 2, 1981.

Police spent a long time chasing a hoaxer

In June 1979, a cassette tape was sent to officers working on the case, and at a glance, it was from the Ripper himself. The recording taunted police: "I see you're still having no luck catching me" and claimed he was planning on killing again, "maybe September or October, even sooner if I get the chance."

The tape was linked to three anonymous letters that had also been sent to police and was played on television and the radio. Thanks to the Wearside accent the tape-maker had, he became known as Wearside Jack. Then, nine weeks after police received the tape, Barbara Leach was killed, just 300 yards from the Bradford police station.

According to The Telegraph, that's when focus shifted from the West to the North East of Yorkshire. Only ... it wasn't the killer. It was a man named John Humble, who — at the time of the killings — was bored. So, he bought a tape, recorded a message, and sent it off. His sister later said (via Chronicle Live) that he had a major beef with the police ever since his stay at the County Durham detention center at a time when offenders housed there were targeted for physical and sexual abuse.

Humble died in 2019, and in a statement to the BBC, former Detective Superintendent Bob Bridgestock suggested that if it hadn't been for the diversion of resources, three lives might have been saved.

Psychics weighed in on catching the Yorkshire Ripper, and they were really wrong

Back in the 1970s, Britain had a super-famous psychic named Doris Stokes (pictured). And sure, people were understandably terrified by the serial killer who was stalking women seemingly at random, so it was at the height of this panic that the Sunday People asked her what her thoughts on the killer were.

She absolutely gave them: The Yorkshire Ripper, she said, was named either Ronnie or Johnny, had a last name that started with "M," lived in either Tyneside or Wearside, was slightly balding, and was clean-shaven. She even worked with an artist to sketch a figure she thought was responsible, and the newspaper ran the story on the front page and asked people to keep an eye out for this guy ... because it was definitely him.

Only, it totally wasn't. It wasn't even close. (But here's a weird footnote: Her description did sort of match Wearside Jack, the Yorkshire Ripper hoaxer who, The Telegraph notes, was named John and was from Wearside.)

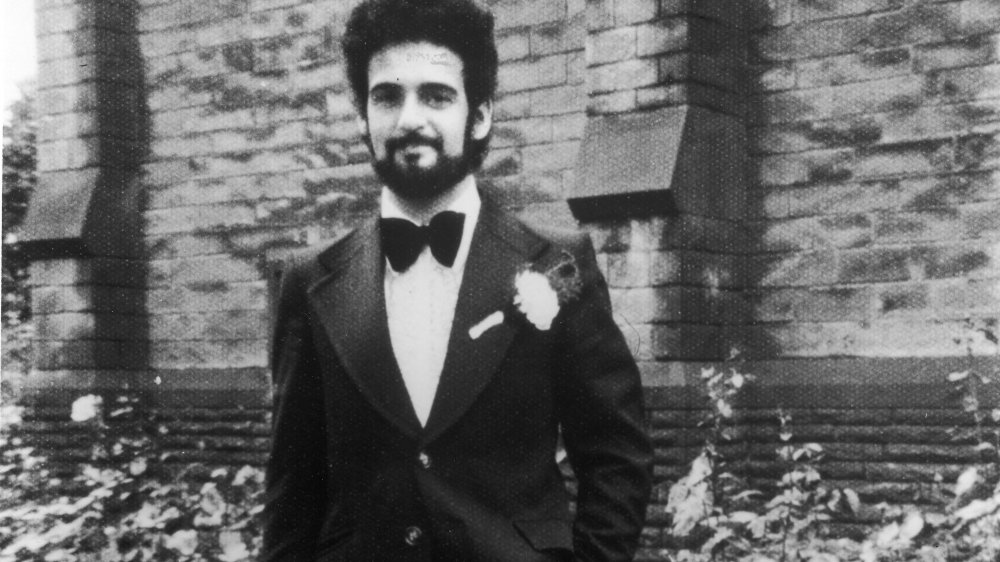

In 1981, police finally arrested the bearded Peter Sutcliffe for the murders, and yes, he confessed to all 13 killings associated with the Yorkshire Ripper. According to The Guardian, the manhunt for the Yorkshire Ripper is just one of the cases that has been held up by the very wrong predictions of psychics and clairvoyants, and the College of Policing says they have discovered "no significant findings through psychics or mediums."

Evidence against the Yorkshire Ripper began to pile up

It's possibly unclear just how many victims the Yorkshire Ripper claimed: The official count is 13 dead and seven more brutally attacked. But some suggest that his attacks went back farther than 1975 — to 1969, and at least four more assaults. Either way, during the Ripper's killing spree, evidence started to come to light.

One victim, Emily Jackson, had been stomped on so hard that her killer left a boot print on her leg. That was in 1976. Then, in 1977, police investigating the murder of Jean Jordan found a £5 note in her handbag. The bill was traced through the bank, and police determined that it had been used as a part of a payroll and could have been given to any one of 8,000 people ... give or take. Marilyn Moore was attacked, survived, and was able to provide a remarkably good description of her attacker. Tire tracks were recovered from the scene of her attack that matched those found at another scene (via All That is Interesting).

And Moore's description wasn't the only one that they had: According to The Guardian, 14-year-old Tracy Browne was not only able to describe her attacker, but she told police that he was a local man.

The arrest of the Yorkshire Ripper

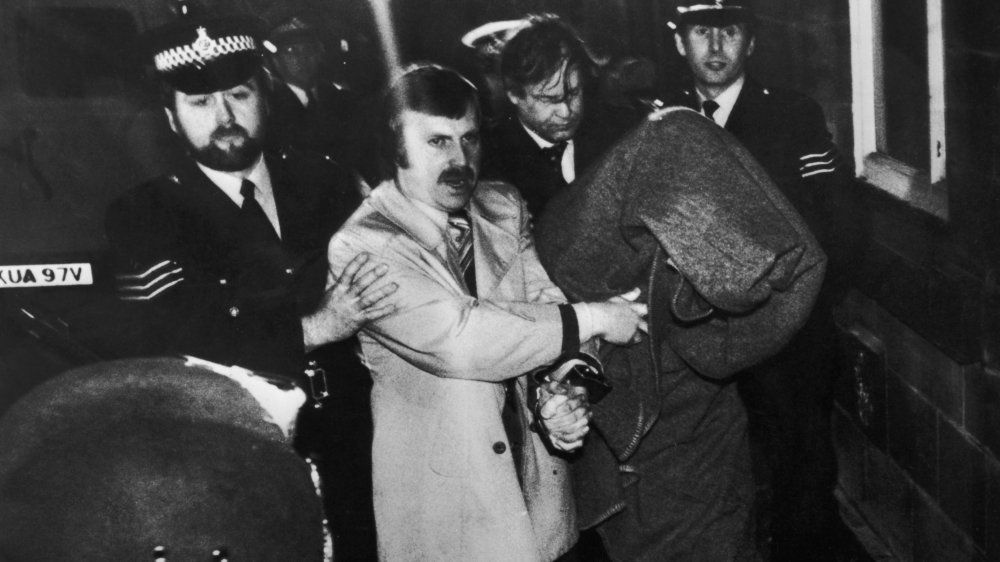

On January 2, 1981, police got what would turn out to be a lucky break. Two officers stopped at an area frequented by sex workers and their clients and approached a car with a man and woman in it. The woman — Olivia Reivers, says I News – claimed the man was her boyfriend. Fortunately, police then ran the plates, which they found didn't match the car. That allowed them to arrest the man, who introduced himself as Peter Williams. First, though, "Williams" asked for a minute to relieve himself, and officers allowed him to go behind a storage tank for some privacy.

It's only when they took him in and held him overnight that they realized (via Crime+Investigation UK) that he matched the description of the Yorkshire Ripper, and his blood type, the relatively rare group B, also matched. When officers returned to the place they'd arrested him and checked behind the storage tank, they found the ball-peen hammer and knife he'd ditched there.

The man — real name: Peter Sutcliffe — confessed on January 4. Once he started talking, what followed was a 15-hour statement in which he explained that it all started when he was 20 years old and working as a gravedigger. The voice of God had commanded him to kill sex workers, he said, so he had embarked on his killing spree.

The Yorkshire Ripper had been questioned a shocking number of times

Peter Sutcliffe's arrest for the non-matching number plates wasn't actually the first time he was in police custody, and it wasn't even the first time he'd been questioned as a Yorkshire Ripper suspect ... not by a long shot.

According to I News, Sutcliffe had actually been questioned a shocking nine times over the course of the investigation. He'd even been one of the thousands of people questioned in connection with the £5 note found on the body of Jean Jordan: He'd spent part of the night at a family party and had been crossed off the list for his alibi.

All That is Interesting says that he was also questioned because of the number of times his vehicle had been spotted around the murder scenes, and in April 1980, he was actually arrested for drunk driving. Sutcliffe was set free while he waited to go on trial for the offense, and during that time, he killed twice and attacked three other women.

The trial of the Yorkshire Ripper

In 2011, the BBC spoke with reporter David St. George, who had worked the Old Bailey press rooms since 1969. As you might expect, that gave him a front-row seat to some of the biggest cases in Britain, and when it came time for Sutcliffe to stand trial, St. George said, "You got a sense at the time that this was something historic."

The trial lasted for two weeks in 1981, and St. George remembered that the court was packed with national and international reporters as well as the families of victims, and when it came to the public gallery, people camped out overnight to get a seat. He said: "Sutcliffe himself was a sorrowful figure in many ways, not very well built and towered over by four prison guards. [...] He really showed no emotion, no smiling, no laughing, and he had this funny softly-spoken voice. [...] He was the most unlikely killer you've ever seen, he didn't fit the bill, but you never can tell."

For the murder charges, Sutcliffe pleaded not guilty. As he was driven to kill by the voices in his head, he claimed, he did plead "guilty to manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility." The trial, St. George said, "was over pretty quickly." The verdict? Guilty of murder, on all counts. The sentence was 20 life sentences, with a minimum of 30 years served before he was eligible to be considered for parole.

The Yorkshire Ripper may be responsible for even more murders

The official victim count for the Yorkshire Ripper is 20: 13 dead and seven more attempted murders. But in 2017, the BBC reported on rumors that he was being questioned in regards to 17 more attacks that remained unsolved. This wasn't the first time there had been rumors that there were more victims out there who hadn't officially been linked to Sutcliffe: An examination into the case that was done after his trial found that the apparent lull in crimes between 1969 (when he first popped up in police reports) and his first official victim in 1975 was unlikely, to say the least.

West Yorkshire police had declined to say what cases they were talking to Sutcliffe about, and in 2018, they officially stated that they had no plans to charge him with more offenses.

According to a report written after the trial (via The Guardian): "We feel it is highly improbable that the crimes in respect of which Sutcliffe has been charged and convicted are the only ones attributable to him." Are there more families out there that should have gotten the closure they deserve?

From Parkhurst to Broadmoor

One of the main issues at Sutcliffe's trial wasn't whether or not he had killed and attacked at least 20 women. It was whether or not he was mentally competent to stand trial ... and that, says The Guardian, is an issue that has lasted far longer than his trial did.

At the trial, there were three psychiatrists called to Sutcliffe's defense. They all agreed on a diagnosis: "encapsulated paranoid schizophrenia." What does that mean? According to an article in the Industrial Psychiatry Journal, "encapsulation" means that a patient can, to some extent, "maintain their original personality and adapt to a normal life." And that kind of makes sense: All That is Interesting looked closer at Sonia Sutcliffe, his wife. She had been struggling with her own diagnosis of schizophrenia and has repeatedly said that she didn't have a clue what was going on ... until Peter was arrested and called her to confess to her directly.

The jury didn't buy it, though, and Sutcliffe was sent to Parkhurst maximum security prison. He was only there until 1984, though, and after being repeatedly attacked himself, he was officially diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and was transferred to Broadmoor (pictured). He refused treatment until 1993, and even then, he was only treated because of an official directive from the Mental Health Commission.

Broadmoor and back again

Incarceration hasn't been kind to the Yorkshire Ripper, who has now taken on his mother's maiden name and goes by Peter Coonan, says the Shropshire Star. He's also been the target of numerous attacks: He is now blind in one eye and has had 30 stitches in his face alone.

And in 2015, his story took yet another turn. The BBC reported that Broadmoor doctors had reassessed his case, and David K. Ho had this to say: "I don't think it's the case that his mental disorder has been completely cured, but I think it perhaps has reached a stage where its symptoms are under control." That meant there was a very good chance that he would be transferred back to prison to continue serving his sentence ... and that's exactly what happened in 2016.

That's when the BBC reported that a health tribunal had declared that the then-70-year-old Coonan was to be moved back to prison to serve the rest of his sentence. Back in 2010, the High Court had decided just how long that was going to be — according to the official statement: "The High Court ordered in 2010 that Peter Coonan should never be released. This was upheld by the Court of Appeal. Our thoughts are with Coonan's victims and their families."

The Byford Report

If you're thinking that it seems like there were a lot of mistakes made in the Yorkshire Ripper case — ones that cost lives — you're not the only one. In 1981, Home Secretary Willie Whitelaw asked Sir Lawrence Byford, Inspector of Constabulary, to conduct a full investigation into, well, the investigation. The high points were published when the report was filed in 1982, but it wasn't until 2006 that the entire document went public — and it was dire stuff.

Byford picked apart the investigation, and according to The Telegraph, his findings involved things like "a catalogue of errors," and the investigation overall was deemed "sadly inefficient." Mistakes ranged from assigning too much credibility to the hoax tape to not confirming alibis that were given and not searching Sutcliffe's car and home when he was investigated early on in the case, when he had already come onto the police's radar for other incidents.

But there's a bit of good news to come out of this, at least: Byford's report didn't just point out problems. It proposed solutions, too. And many of those solutions were taken seriously, from changing some standard investigative procedures to — perhaps most importantly — urging the development and installation of computers in law enforcement offices around the world.