The Messed Up Truth Of The Council Of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea is one of the most significant, and as such one of the most famous, events in the history of the Christian church. For the first time, church leaders, assembled by Rome's first Christian emperor after centuries of persecution, gathered together to really, like, hash out the big issues. It was time to really make this thing legit. Time to make a clear and universal statement of faith. The church was in danger, or so the emperor and the bishops believed, and radical and passionate action was needed to save it.

It would be difficult to argue that Christianity isn't still around, so by that measure, the Council of Nicaea was a success. But was it really a success? Did it perhaps ... set an extremely dangerous and violent precedent? Maybe! Here's a look at what did — and didn't — happen at the First Council of Nicaea.

What even was the Council of Nicaea?

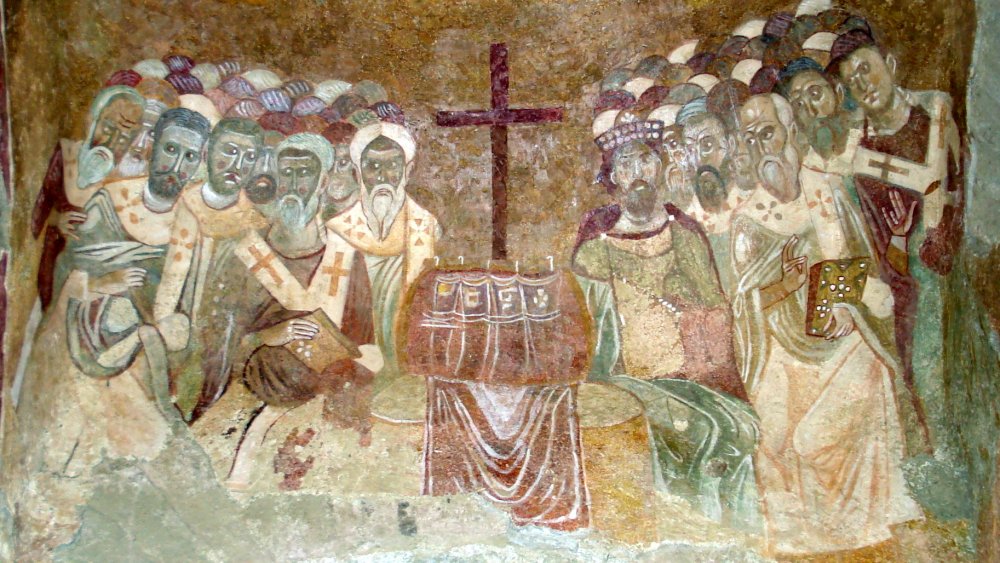

So we know the First Council of Nicaea was historically important and gets name-dropped a lot, but why? What's the big deal about a group of dudes with beards and pointy hats getting together to talk about church rules? Well, as the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, the Council of Nicaea was the first ecumenical council of the Christian church. "Ecumenical" comes from the Greek word oikoumenē, meaning "the inhabited world," and, as such, means it was the first gathering of bishops — overseers of all the churches in a particular region — from the entire known world of Christianity at that time (mostly southern Europe, northern Africa, and the Middle East) to discuss a major issue.

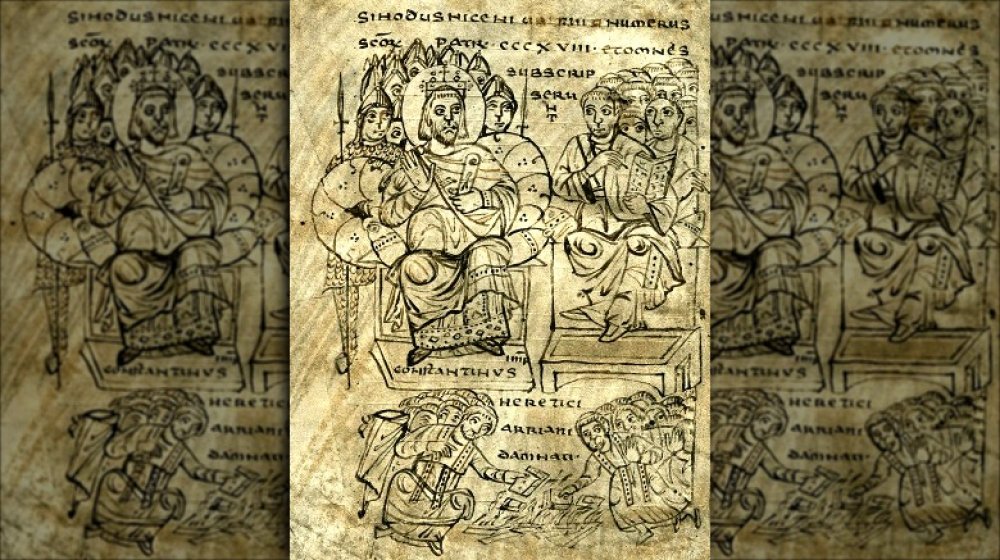

The council was convened in 325 CE by the emperor Constantine the Great, generally regarded as the first Christian Roman emperor, in the ancient city of Nicaea, which is known today as İznik, Turkey. While not literally every bishop in the world was actually present — notably absent was Pope Sylvester I, who did at least send representatives – tradition holds that 318 bishops were present, largely representing the Eastern portion of the church. Constantine called the council together in order to address issues of division within the church, hoping to re-establish peace religiously as he had just done politically by defeating his imperial rival Licinius.

The thing you think happened at Nicaea didn't happen

Before we dive deep into what the Council of Nicaea actually was, let's take a quick look at what it definitely wasn't. A popular and oft-repeated myth is that the emperor and the church fathers decided which books would become biblical canon and which books didn't make the cut. As HowStuffWorks points out, this idea got a huge boost when Dan Brown repeated it in his garbagetown bestseller The Da Vinci Code, which sold a lot of people on a lot of fake ideas. The myth predates Brown by centuries, though, and even the 18th-century French satirist Voltaire said that the bishops picked the books of the Bible by placing all the candidates on a table and seeing which ones fell off.

The fact is that there's no evidence whatsoever that there was any one single council or other gathering at which a bunch of church leaders decided what was real and what was fake. Rather, the canonization of the New Testament was a centuries-long process of debate and analysis in which some texts were believed to have apostolic authority, authentic antiquity, and orthodoxy. Even today, the Protestant, Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Ethiopian Orthodox churches don't agree about which books are canon, so the idea that this was "decided" in 325 is incredibly silly.

The Arian controversy

If the Council of Nicaea wasn't about deciding which books of the Bible were canon, what was it about? Well, a number of different issues were discussed at this meeting, but the primary concern and the main cause for division within the church was the issue of a priest named Arius of Alexandria and his increasing popularity among Christians in Alexandria and beyond. Arius espoused a theological doctrine that got named after him, Arianism, not to be confused with Aryanism (this one's got nothing to do with little blond-headed Nazi children) that was extremely troubling to more orthodox priests and bishops.

As the Catholic Encyclopedia explains, Arianism is an attempt to rationalize the relationship between God the Father and Jesus the Son. If Jesus is the son of God, that means God came first, like, logically, right? The implication of this, however, is that there existed a — well, not a time, as the division of the persons of God is supposed to predate the concept of time — but a circumstance in which Jesus didn't exist, meaning he is not truly eternal. This is counter to the Gospel of John, which identifies Jesus as the Word, who was with God in the beginning and was God. Arius said that if Jesus was begotten, only God the Father exists without origin. To most bishops, this was heresy and absolutely would not stand.

The surprising popularity of heresy

While the distinction between Jesus being "begotten" by God versus being "made" by God might seem like an extremely minor nitpick from a modern perspective, to the early church, which had only just gained legitimacy after centuries of persecution, nailing this one thing down was incredibly important. According to Britannica, Arianism is a Unitarian doctrine, in the sense that it focuses on the uniqueness of God at the expense of the core orthodox doctrine of the Trinity, in which God is expressed as three persons, e.g. three distinct but indivisible aspects. For Arius, the fact that Jesus was not self-existent (that is, that he had to be created) means that he must be subordinated to God the Father. To a mainstream Christian at that time, this was a denial of the divinity of Christ.

Phrased that way, it might seem like Arianism would be shocking to most Christians. And yet, Arianism was incredibly popular in both the Western and Eastern halves of the Roman Empire. The Council of Nicaea wasn't even the first attempt to stop Arius. In 321, the bishop of Alexandria convoked a council of 100 bishops to denounce Arius and his doctrine, but he continued to gain followers until he was driven out of Egypt. Then he just went and recruited more followers in Palestine. It was at this point that Constantine made like Gary Oldman in The Professional and shouted, "Bring me everyone!"

Did Santa Claus deck a guy at the Council of Nicaea?

To a modern audience, likely the most famous name among the bishops in attendance at the Council of Nicaea was Nicholas of Myra. Yeah, that Saint Nicholas. The Santa Claus one. According to the St. Nicholas Center, as Arius was vigorously defending his views on the Trinity (or the lack thereof) on the council floor, Nicholas got so hot at the heresy that he stood up, strode across the floor, and decked Arius cold across the face. It turns out it's illegal to strike anyone in front of the emperor, so the story goes that Nicholas was stripped of his episcopal office and placed in jail. The legend goes on to say that that night, the Virgin Mary and Jesus appeared to Nicholas, freeing him from his chains and returning to him his bishop's robes. When Constantine saw this, he reinstated him as the bishop of Myra.

Now, even if we ignore the part about Mary's ghost busting Saint Nick out of jail, is the striking part of the story true? Well, almost definitely not. While some accounts of the council list Nicholas among the attendees, not all of them do. The ones that include him date much later, and the punching story doesn't pop up until 1,000 years after the council. Also, the original version just says he hit "an Arian," not Arius himself. Still a great story, though.

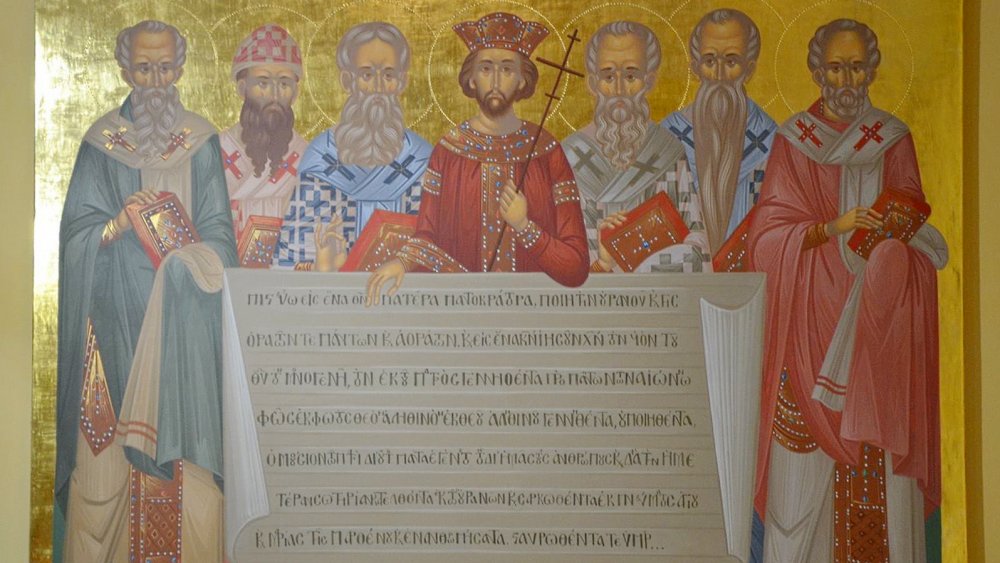

A universal statement of faith

The bishops at the Council of Nicaea wanted to make a definitive statement to make no bones about their denunciation of the Arian belief that Jesus was somehow subordinate to God the Father. What resulted was the Nicene Creed, the first clear and universal statement of Christian belief ever officially issued by the Church. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the creed was altered a few times to respond to newly arising forms of Arianism, but most were variants on the statement from Nicaea, and the version that stuck was confirmed at the Council of Constantinople in 381.

Many elements of the creed exist specifically to counter Arianism: "[I believe in] in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and born of the Father before all ages. (God of God) light of light, true God of true God. Begotten not made, consubstantial to the Father, by whom all things were made." The key ideas here are that Jesus was "begotten, not made," that he was "true God of true God," and that he was "consubstantial to the Father," a term that was at the crux of the arguments at Nicaea: Were the Father and the Son the same stuff? Nicaea said yes, and so do most modern Christians, as the Nicene Creed is still used today in Catholic, Orthodox, and most Protestant churches.

Making Easter less Jewish

While the Arian controversy was the major issue addressed by the First Council of Nicaea, it wasn't the only one. Another big question raised among the bishops was, "How do we know when Easter is?" At face value, this might seem like a silly question, but then ask yourself, "Hey, what date is Easter next year?" Can you do it without Googling? You can't, liar.

Since the beginning, the date of Easter had been tied to the Jewish observance of Passover. However, as Christianity.com explains, the bishops at Nicaea did not want their holy day to be beholden to Jewish observance, because anti-Semitism. So while the church had originally held Easter on the Sunday nearest to Passover or even just on Passover, the new rule was that Easter had to be a Sunday and could not be on Passover.

The solution was that Easter would be held each year on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, which — you are correct — definitely sounds like some Wiccan business and not orthodox Christianity, but here we are. The process of determining these dates in advance is a formula known as Computus, which sounds like a Legion of Super-Heroes villain but is just the Latin word for "calculation." As a result, Easter always falls somewhere between March 22 and April 25. Well, in the Western church. Eastern churches still use the Julian calendar, which is a whole other kettle of fish.

The other church schism

Unfortunately, Arius wasn't the only troublemaker that the early church had to deal with at the Council of Nicaea. The bishop of the city of Lycopolis in Egypt, Melitius (also sometimes spelled Meletius), was causing problems of his own. The Catholic Encyclopedia explains that Melitius was a high-ranking bishop, second only to Peter of Alexandria in all of Egypt, which is what made his misconduct and insubordination so troubling. While the various sources can make it difficult to discern exactly what Melitius' main crime was (including a claim that he was deposed as a bishop for sacrificing to idols), the central issue seemed to be that he was unwilling to readily accept back into the church Christians who had renounced the faith under torture by the Roman persecution. While most bishops were eager to accept those who repented of such action, Melitius refused.

Even after being denounced as a disturber of the peace, Melitius continued to gain support, and he ordained those who supported him, even from outside his own diocese (another no-no). At the time of the Council of Nicaea, the Melitian Schism (the name for his breakaway church, though they called themselves the Church of Martyrs) included dozens of bishops and priests. The council tried to make peace with Melitius by allowing him to remain bishop but said he had to quit ordaining outside his diocese. It, uh, didn't work great.

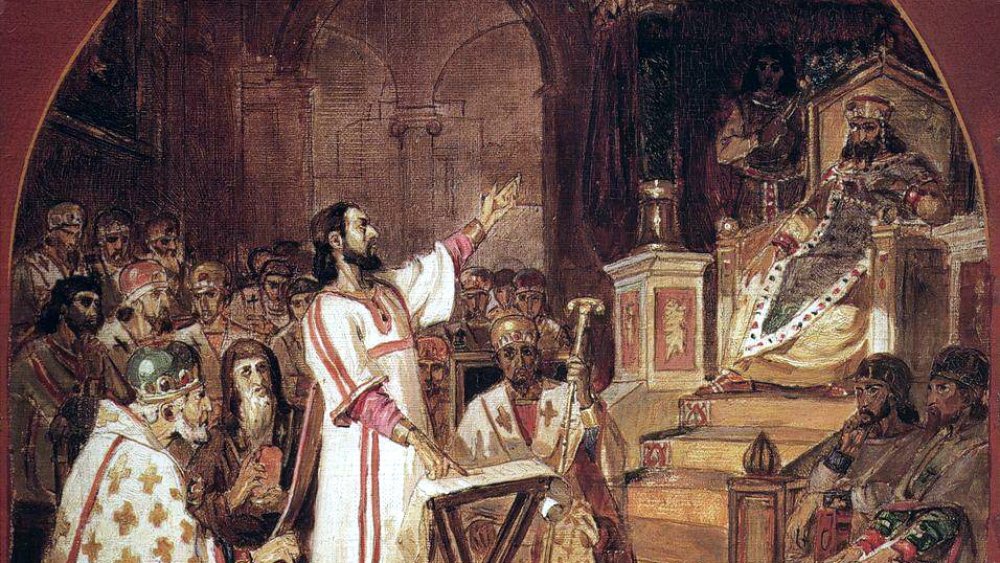

Orthodoxy, or else

The firm conclusion of the Council of Nicaea regarding the Arian controversy was that the church needed to use precise language regarding the nature of Christ. As Pastor Marc Minter explains, the Greek word used in the original statement of belief from Nicaea was homoousious, literally "of the same substance," which is the word that gets translated as "consubstantial" in the English version of the Nicene Creed. The idea that "there was once when Christ was not" and that Jesus was somehow changed from his coeternal being were deemed heretical and anathema, and all the bishops had to sign their names agreeing to the statement that Christ was consubstantial to the Father or else be not only excommunicated from the church but exiled from the empire.

Some theologians present agreed to the terms of the Nicene Creed but then later tried to fudge their statements of orthodoxy by claiming that Christ was not homoousious to the Father (of the same substance) but homoiousios (of similar substance) in order to emphasize distinctions between the persons of the Trinity. This new breed of Arianism didn't fly any better with the orthodox bishops, and the "one letter off" version was considered just as heretical as the pure strain. Nevertheless, even the threat of excommunication and exile didn't dissuade some Christians from leaning toward Arius' way of thinking.

Church and state make a love connection

The results of the Council of Nicaea included Arianism being denounced in no uncertain terms. According to OverviewBible, not only were Arius and the only two bishops who didn't flip on him (he had started the council with 22 bishops in his corner — they didn't hold up to the pressure) exiled to Illyria in the Balkan Peninsula, but Constantine ordered that all of Arius' writings be burned and that anyone found with copies of his writings on their person be put to death. Such steps may seem severe (they were), but they were seen as necessary for the church to keep from self-destructing at a pivotal point in the history of Christianity.

One of the long-lasting consequences of the council, however, is that it set a precedent for the emperor using his authority to establish and enforce church rulings. If Constantine can say, "Believe this specific thing about the nature of God or die," then that has startling implications. It also marks the full swing of the pendulum for Christianity: In a handful of years, it had gone from a religion forbidden and persecuted by the empire to one inextricably intermingled with it, where the emperor himself was ruling on theology. This tangling of church and state would subsequently be at the heart of European history for centuries, where popes and kings would struggle against each other for primacy.

Constantine probably wasn't even really a Christian

The commonly repeated factoid is that Constantine the Great was the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire. To paraphrase the God of Thunder in Thor: Ragnarok, "Was he, though?" As Ancient Origins says, Constantine is certainly well-known for his dream-inspired conversion in which a Christian symbol led him to victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Edict of Milan making Christianity legal within the Roman Empire, and the building of some of the most famous churches in the world, including St. Peter's Basilica and the Hagia Sophia. He also, of course, convened and oversaw the First Council of Nicaea, a pivotal moment in church history. However, by the time of the Council of Nicaea, Constantine hadn't even been baptized yet, despite his professed conversion following his prophetic dream having occurred some 13 years before. Constantine would not, in fact, be baptized until he lay on his deathbed in 337, believing it was best to be forgiven of all his sins as emperor at once.

In fact, there is much evidence to suggest that for most of his life, Constantine worshiped the sun. The Arch of Constantine, a triumphal monument that stands to this day, built after Constantine's official conversion, bears no symbols of Christianity, not even the chi-rho symbol to which he attributed his victory, but rather the god of the sun. Constantine didn't care about the theology of the Council of Nicaea — he just wanted peace.

The Council of Nicaea didn't even work

Well, even if the Council of Nicaea established a knotty link between church and state and was overseen by someone who probably didn't even care about the controversies at hand, at least it succeeded in wiping out the Arian heresy and mending the Melitian schism, the two great threats to the church at the time, right? Uhh, well ... no.

According to OverviewBible, as time went on, Arianism crept its way back into popularity to the point that Constantine even started to tolerate the Arians. (Keep in mind that peace and unity were all he cared about.) In fact, the priest who baptized Constantine on his deathbed was Eusebius of Nicomedia, an Arian. After Constantine, there were a number of Arian emperors, including his son Constantine II and later Constantius II. (These are definitely different people.) Soon enough, the tide turned, and many of the bishops who had excommunicated Arius were themselves excommunicated, including Athanasius, who had been orthodoxy's most stalwart defender at the council. It took until the end of the fourth century for non-Arian emperors Gratian and Theodosius I to finally quash Arianism within Rome.

That wasn't the end of it, though. As Britannica relates, Arianism was extremely popular among the Germanic tribes that ended up sacking Rome, and it remained so until well into the seventh century. The council failed to suppress the Melitian schism, too: His church lasted for over 100 more years.