The Messed Up History Of Disco

Disco was arguably the hippest music craze of the 1970s. Derived from the dance-oriented nightclub term discotheque, the music genre-turned-cultural-movement was a fusion of Motown, funk, soul, and salsa. It's known for its interracial music groups, dance numbers, loud and colorful costume-clothing, iconic film Saturday Night Fever, and lots of glitter.

Initially ignored by radio DJs who saw it as an underground fringe movement, the genre ultimately transcended racial and sexual identity, was embraced by the hottest celebrities, and eventually broke into the mainstream.

But disco has a dark side, the movement was never accepted by a large group of people. Many of its brightest stars fell victim to tragedy, and the cultural phenomena would even come to be blamed by some for spreading the HIV/AIDS virus. From the fall of Studio 54 to Disco Demolition Night, those at the top of the disco charts would soon learn that not all that glitters is gold.

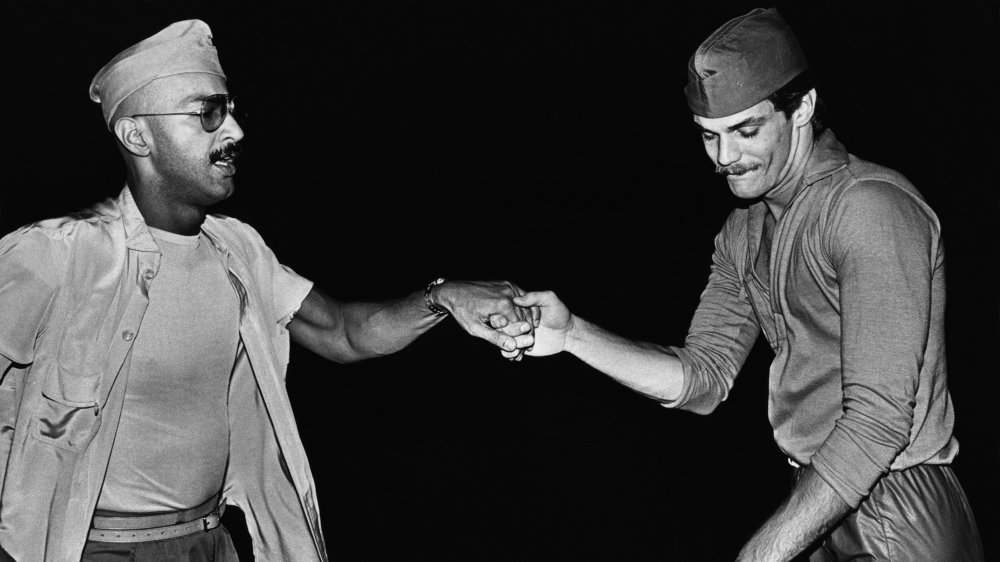

Private underground disco dance parties

In the early 1970s, disco is thought to have emerged from an urban subculture that featured marginalized artists otherwise shut out of the mainstream, such as African Americans, Latinos, and the LGBTQ community. DJs in New York City like David Mancuso created underground clubs to showcase these artists and had to make arrangements with the police not to raid them.

Mancuso, known as one of the most influential figures in nightlife history, threw epic underground parties every Saturday night at his apartment, known as the Loft, until 6 a.m. His secret soirees combined counterculture groups with the latest in sound technology.

In the throes of the gay liberation and civil rights movement, people from all walks of life gathered at similar house parties like Mancuso's before disco counterculture bled into the mainstream as the decade progressed, and marginalized minorities of society could come out and party in public.

Influential NYC sound system builder Alex Rosner remembered the Loft's underground vibe as "about sixty percent black and seventy percent gay. There was a mix of sexual orientation, there was a mix of races." The Loft even provided refuge for many "gay, Black, and Latino youth" after they were kicked out of their houses by parents unaccepting of their lifestyle, according to NPR. Meanwhile, this was at a time when public nightclubs were being raided and members of the LGBTQ community were being openly abused and arrested by the police.

The reign of Disco Biscuits

The 1970s were also the height of the Disco Biscuit. Also known as Quaaludes, Disco Biscuits became a club favorite because they were known to increase sexual arousal. What was originally intended to act as a painkiller and sleep aid soon became known as a drug that released inhibitions and had a euphoric effect when mixed with alcohol. Unfortunately, this also made it easy to take advantage of people while they were under the drug's spell. By 1972, the drug became so popular, it created political panic.

Congress began hearings to debate whether the drug should be classified as a Schedule II Controlled Substance. Medical journals and the media also began to report on its dangers. But if you think that is why the drug was banned by the Food and Drug Administration, think again.

Medically known as methaqualone, "Ludes" were outlawed in the United States in 1982 because the FDA deemed it unprofitable. "Quaaludes accounted for less than 2 percent of our sales but created 98 percent of our headaches," chairman of the William H. Rorer pharmaceuticals company told the press in 1981. Not that making it illegal stopped people from ingesting the drug in nightclubs.

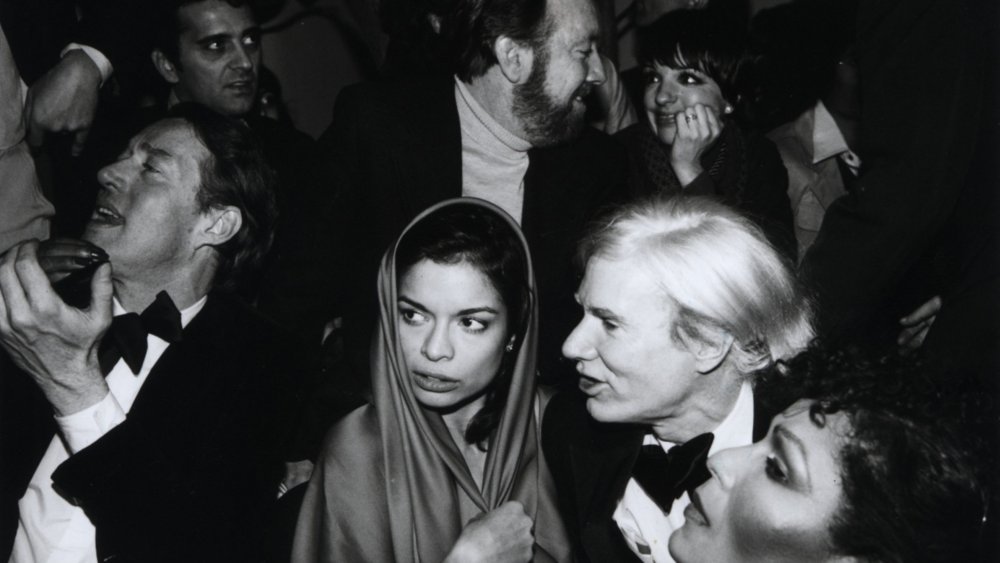

Studio 54 rises and falls

Velvet ropes, doormen, VIP lists, and flashy DJs — these fads started during the disco era. Disco's most infamous discotheque was undoubtedly Studio 54 in New York City, frequented by A-listers like Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger. "Studio was more than a discotheque. It was more than a night club. It was a cultural phenomenon," owner Ian Schrager said in a CBS News interview in 2018.

The nightclub opened in 1977, and some truly crazy stuff happened there. Like the night they unleashed four tons of glitter onto the floor. "You would see it in people's homes six months later, and you knew they'd been at Studio 54 on New Year's," owner Ian Schrager said.

But the fun and games would soon come to an end. In 1978, Studio 54 was raided by IRS agents for drugs and tax evasion. It probably didn't help that co-owner Steve Rubell had said that "only the Mafia does better" when it came to making money. The IRS perked up at that comment. Apparently Studio 54 had paid only $8,000 in taxes in 1977. The feds followed, finding mass amounts of Quaaludes and cocaine stored at the club. But owners Schrager and Rubell got courted off to jail in style. Celebrities, including Jack Nicholson and Gia Carangi, joined the two as they were serenaded by Liza Minnelli and Diana Ross for a proper bon voyage.

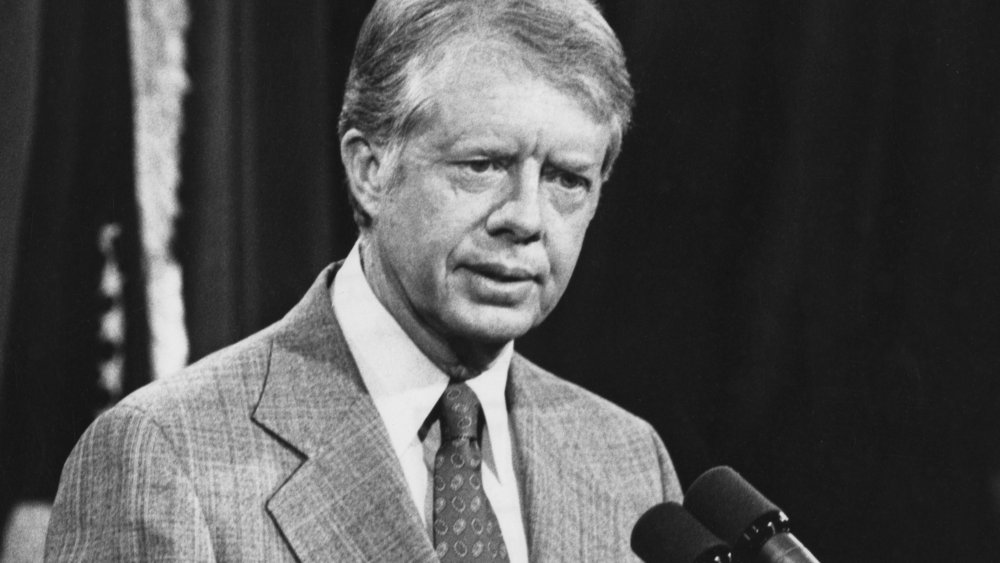

Jimmy Carter's administration and Studio 54

President Jimmy Carter dodged a political and legal bullet when his team averted a drug scandal that could have shaken his already rocky presidency in 1979. President Carter's Chief of Staff, Hamilton Jordan, was alleged to have been spotted snorting cocaine in Studio 54 the year before. It turns out it may have been a setup orchestrated by the infamous conservative lawyer, Roy Cohn.

There was a version of the story that included Carter's Press Secretary Jody Powell, who reportedly may have been with Jordan at the club. The FBI questioned them both, but they denied any wrongdoing. Jordan would later admit to attending Studio 54 briefly but claimed he did not use drugs. According to People Magazine in 1979, 'Ham' Jordan already had "a reputation as a partygoer."

How did Roy Cohn enter into it? Cohn had been hired by Studio 54's two owners to help them with obstruction of justice and conspiracy charges. When Cohn heard through the grapevine that Jordan and Powell had attended Studio 54, he saw an opportunity. He taped a statement from the dealer who allegedly sold drugs to Jordan and tipped off the FBI, hoping to hurt Carter's administration.

Luckily for Jordan, Powell, and the 39th President of the United States, the cocaine use allegations never lead to an indictment.

Grace Jones' breakdown on live television

In November of 1980, disco superstar and Studio 54 regular Grace Jones was a guest on Russell Harty, and we're guessing Russell Harty regretted having her. During the show, Grace kept getting more and more aggravated that Russell kept turning away from her. Then she physically attacked him. "Don't turn your back on me anymore," Jones said before starting to whack him on the shoulder.

In Grace Jones's memoir, she recalls the interview and gives a rather bizarre explanation for her behavior. Nonetheless, it's all very on-brand. According to Jones, she was "covered in pigeon s***" at the time, her sinuses were infected, and she was on some "really bad coke." She also recalls that the rehearsal went quite differently than the live event. "The three of us politely sat all facing each other in a semicircle. There didn't seem to be anything to worry about." Jones also claims she felt provoked.

In Grace Jones's defense, it is rude to turn your back on someone, and then to poke fun at them on the air while they sit right next to you. So maybe Harty was simply getting his comeuppance.

Nevertheless, it's a tad unfortunate that the clip of this interview is the first thing that comes up on YouTube when you search this larger-than-life, signature artist of disco culture's name. In 1975, Grace Jones's "I Need a Man" had topped the Billboard dance chart. But that's show business.

The AIDS epidemic reaches the clubs

Before disco culture, the LGBTQ community was completely underground, and constantly in danger of breaking the law simply for expressing themselves. In the disco era, they finally felt safe to meet up en masse and dance the night away. But around the time of this newfound freedom also came the emergence of a horrifying disease.

As the disco era began dying down in 1980, HIV/AIDS was still an unknown virus and would go unrecognized until 1983 in the United States. In 2016, NBC News reported on a research study that concluded that the HIV virus began to spread in New York City around 1970. "HIV had spread to a large number of people many years before AIDS was noticed," virus expert at the University of Arizona's Michael Worobey told reporters. The findings also suggest that the virus moved from New York City to San Francisco around 1976.

Tragically, there was very little government support for those suffering from the virus, which became a stigma used to further discriminate against minorities. At the time, it disproportionately affected homosexual men. "Club culture inevitably affected and was affected by the epidemic," Steve Weinstein remarked in Vice. "Often, I was relieved to see people at the Saint at Large [club] parties; I had assumed they had died in the interim."

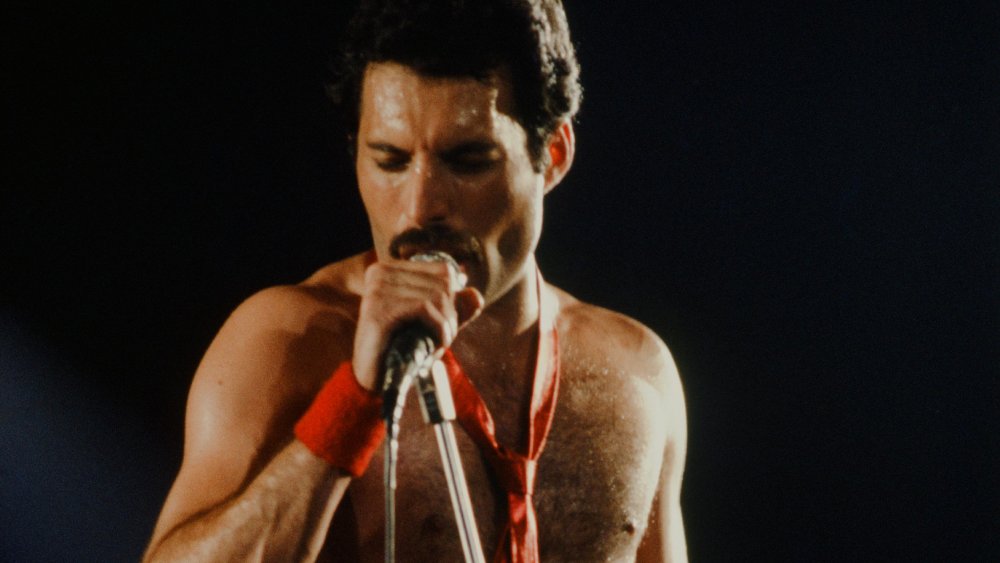

Freddie Mercury's tragic end

Freddie Mercury was a disco hero and gay icon of the '70s and '80s. His band Queen showcased classic disco elements: soaring vocals, catchy bass lines, and empowerment ballads. However, tragically, Mercury's HIV diagnosis in 1987 caused the disco legend to slowly dissipate in the public eye, growing noticeably thin and feeble.

While the HIV epidemic was thought to have been widely spread by the gay community, the virus truly left everyone vulnerable. It was actually more common to contract the virus through hypodermic needles and through people of any sexual preference who practiced unprotected sex — especially those with multiple partners. Mercury was open about having sex often, and with many different partners. "I'm doing everything with everybody," he once said.

Unfortunately, public health information at the time Mercury was diagnosed was lacking, and he tragically died before the development of the antiretroviral combination treatment that could have helped him live longer. There was wide prejudice about the virus. In a Los Angeles Times poll, 42 percent of participants wanted to close gay bars in the wake of the virus. Even the band Skid Row was offensively outspoken about their disdain for the gay community at the time.

Perhaps the most tragic part of Freddie Mercury's last days was the gaggle of paparazzi and celebrity-obsessed people who lurked outside of his home in London while he lay dying to try to catch a glimpse of the rock legend.

Disco star Sylvester speaks out before his death

Sylvester James, known simply as Sylvester, was an openly gay performer in the late '70s and early '80s. He made a splash with his exotic drag ensembles and his trademark falsetto voice that made him a stand-out talent at the height of the disco age. When he was diagnosed as HIV-positive, he made a conscious effort to educate the LGBTQ community about the virus, particularly within the African-American community. Sylvester still sat for interviews to inform the public and remained candid that he was dying of AIDS. Unfortunately, he lost his battle to the virus in 1988.

Known as the "Queen of Disco," Sylvester's biggest disco hits include "Dance (Disco Heat), "Body Strong," and the disco party anthem "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)." All were dropped at the height of disco fever in the late 1970s.

Sylvester's biographer Joshua Gamson said, "You've got the words of a person who is just matter-of-fact about their sexual desires, about the freedom to do with their bodies and their desires whatever they want to do, and you can dance to it!" While he died too young, Sylvester left a powerful, positive legacy. According to AJC, Sylvester requested that he be buried in a red kimono and matching lipstick — what's more disco than that?

Disco Demolition Night

Disco was at peak popularity in 1979. However, the anti-disco movement had finally gained steam and would reach its boiling point in Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois on July 12 of that year. During a MLB promotional event, a giant box of disco records was burned, and a riot ensued. Many believe the anti-disco zealots were motivated by racism and homophobic sentiment. The night symbolized the beginning of the end of disco.

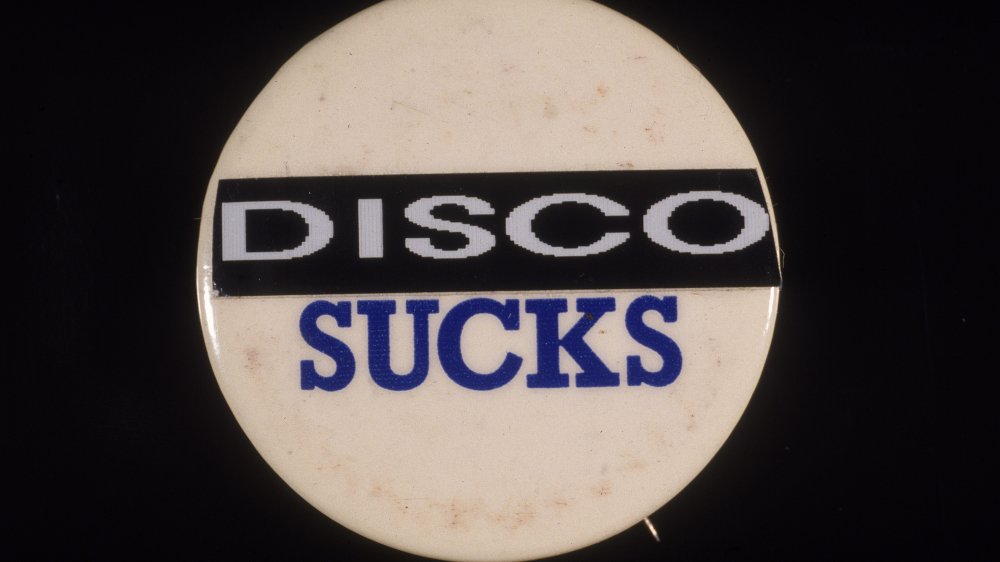

The backlash, which had been steadily brewing for years, came to a head in 1978 when shock-jock DJ Steve Dahl was fired when his radio station began to play nothing but disco. He then coined the phrase, "Disco sucks!" Dahl was the orchestrator of Disco Demolition Night. At the time, fans were asked to bring disco albums in exchange for cheap admission to a Detroit Tigers/Chicago White Sox doubleheader at Chicago's Comiskey Park. The event drew a crowd of about 48,000.

Someone lit a fuse and the compiled records exploded on the field, leaving a smoking crater. Records were "whizzing about like frisbees," and the crowd stormed the field, causing the White Sox to forfeit the game, per Groovy History. Darlene Jackson, who was 10 years old at the time, remembers watching the event on television. "They got really, I would say, violent," she told WBUR. "It was so primal and tribal."

Just last year, the Chicago White Sox actually commemorated the anniversary as a promotional event, to much disgust.

Gloria Gaynor was suspicious of the Death to Disco movement

The Grammy-winning "I Will Survive" legend Gloria Gaynor suspected that the Disco Demolition night in 1979 didn't come out of nowhere, and was supported by some in the music industry. At the time, Gaynor was at the top of the charts. She believed it was a racially-charged monetary decision set up by the record companies. By 1979, the American music industry was undergoing its worst slump in decades, and disco was considered the culprit, according to The Music Origins Project.

Gloria Gaynor, among other disco artists, were suspicious that rock music producers staged the demolition because they were losing money. A representative for A&M Records was reportedly quoted by the Los Angeles Times saying that "radio is really desperate for rock product" and "looking for some white rock-n-roll."

Rock critic Dave Marsh told Today that he was appalled by the events of Disco Demolition Night: "It was your most paranoid fantasy about where the ethnic cleansing of the rock radio could ultimately lead. It was everything you had feared come to life." Meanwhile, producer Nile Rodgers, the guitarist of the disco band Chic, who later became known for his work with Madonna, likened the movement to "Nazi book-burning." "This is America, the home of jazz and rock and people were now afraid even to say the word 'disco,'" Rodgers explained to Independent.

Disco club culture changes shape

After 1980, "disco" saw a sharp decline, Today reports. Donna Summer and Michael Jackson songs still populated the airwaves, but now these disco jams were labeled "dance," "pop," or "electronic" music. "Retreating underground to its original audience, disco became arguably more adventurous and creative than ever," the Guardian notes.

By the 1990s, there was a wave of 1970s nostalgia. The glittery hedonism of disco had inspired a resurgence of nightclub culture. Films like Boogie Nights, Last Days of Disco, and chart-toppers like Pulp's "Disco 2000" proved '90s club culture was a direct descendant of disco.

This mutated version of disco culture was not without its own tragedies. On March 18, 1996, a deadly fire broke out in the Philippines at Ozone Disco, an immensely popular nightclub for students. The fire would kill nearly half of its club-goers that night (162 out of 350 guests) and is known as the worst fire in Philippines history and one of the worst blazes to ever hit a nightclub. "It was like hell," said Ozone Disco's disk jockey Marvin Reyes in an interview with The New York Times.

The 1999 memoir Disco Bloodbath by former club kid James St. James detailed the truly messed up tale of the murder of drug dealer Andre 'Angel' Melendez in 1996. Michael Alig, a party promoter known as the ringleader of a group of Club Kids in New York City, claims he and his friends were on multiple drugs at the time of the murder, which sent shock waves throughout the city, per British Journal of Photography. Many iconic nightclubs closed after the incident.