The Medicinal History Of Sodas Explained

Soda, pop, soda pop, coke, soft drinks, fizzy drinks, tonic ... whatever you call what the Pop Vs. Soda project calls "carbonated soft drinks," you probably know them as unhealthy. Per the Washington Post reporting on research from JAMA Internal Medicine, "regular consumption of soft drinks — both sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened — was associated with a greater risk of all causes of death ... including diseases of the liver, appendix, pancreas, and intestines." The article goes on to quote the American Heart Association's caution that "sweetened drinks are the biggest source of added sugar in our diet."

Early proprietors and drinkers of the earliest versions of soda wouldn't believe the anti-soda stances of today. From their beginnings in the 1760s right up into the 20th century, sodas were conceived, marketed, and imbibed as "health tonics" that were said to cure all sorts of physical, emotional, and psychological problems. They often didn't even contain sugar, but much unhealthier ingredients found their way into soda recipes over the decades and were often advertised as beneficial to human bodies when they were, in fact, downright dangerous.

The beginning: Impregnating Water with Fixed Air

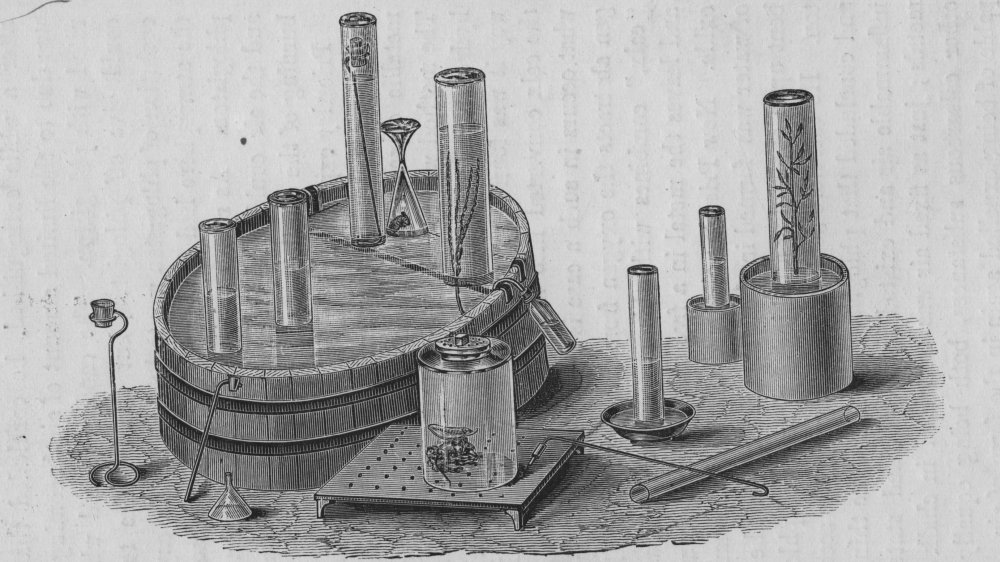

The earliest days of the history of soda can be traced back to 1767. Per Britannica, British chemist Joseph Priestley is best known for his contributions to the chemistry of gases; he discovered the existence of 10 gasses, including nitric oxide, ammonia, nitrogen, and, everyone's favorite, oxygen. Inspired by Francis Bacon's philosophy that "social progress required the development of a science-based commerce" and influenced by "the multitude of diseases that plagued the growing populations in towns," Priestley designed an apparatus (pictured above) that added carbonation to water.

Priestley theorized that carbonated water would provide medicinal relief to patients suffering from scurvy and other illnesses. He didn't market his invention, but offered his recipe to Captain James Cook and his crew when they set off on a Pacific voyage; it didn't work as medicine, but this was probably the first instance of people making and consuming carbonated water outside of a laboratory, according to DrinkingCup.net. Priestley published the results of his experiments in a paper titled Impregnating Water with Fixed Air.

A Bewley's Mephitic Julep for what ails ya

According to the 1991 pamphlet Soft Drinks: Their Origins and History, apothecary Thomas Henry of Manchester, England was "first to sell artificial mineral water to the general public for medicinal purposes, beginning in the 1770s." He had succcess by commercially manufacturing an earlier recipe for "Bewley's Mephitic Julep," which called for adding fossil alkali to water and "throw[ing] in streams of fixed air until all the alkaline taste is destroyed." Henry suggested this concoction be used for relief from "putrid fevers, scurvy, dysentery, bilious vomiting, etc." and recommended that all bottles containing the water be tightly corked and sealed in order to retain carbonation.

By the end of the decade, Henry was also making and selling "Pyrmont and Seltzer waters," which led other apothecaries to create and prescribe their own soda waters, as pictured in the advertisement for Guy's Tonic. According to an issue of The British Medical Journal from 1911, Guy's Tonic continued to be recommended for a variety of ailments, from "disorders of the digestive system" to "disorders of the blood" to "nervous maladies" such as sleeplessness and alcoholism right into the 20 century.

Schweppervescence, then and now

Meanwhile, a German watchmaker living in Geneva, Switzerland read Priestley's paper and was inspired to do some chemistry of his own. According to DrinkingCup.net, Johann Jacob Schweppe learned to "simplify carbonation through the application of two common compounds — sodium bicarbonate and tartaric acid," which made it possible to create more bubbly water in a shorter amount of time via his development of a "hand cranked compression pump," per Collectors Weekly. He called his process the Geneva System and set up mass production in 1783 under the name Schweppes.

Carbonated water was still marketed primarily for medicinal purposes. When Schweppes moved his operation to London in 1792 and started the first Schweppes factory, he marketed "three different strengths of bubbles" for indigestion, kidney disorder, and "violent bladder or kidney stone distress," respectively, DrinkingCup.net says. Schweppes products remain popular to this day, although they are now used strictly for hydration and refreshment purposes, and are remembered for their creative advertising over the centuries. These include their coining of the portmanteau "Schweppervescence" in 1945 to describe the effervescent nature of their sodas and tonics, an running a British campaign for fourteen years featuring the fictional location of Schweppshire, "a fanciful county in Great Britain with its own language, cast of characters and coat of arms."

Benjamin Silliman's Carbonation Nation

Collectors Weekly quotes Anne Funderberg, author of Sundae Best: A History of Soda Fountains: "If I were going to single out one person as creating the carbonated drink industry, I would give credit to Benjamin Silliman, even though he eventually failed financially." Silliman was a professor of chemistry at Yale University and, per ConnecticutHistory.org, studied Joseph Priestley's work and "proposed that the medicinal effects of natural mineral waters could be mass-produced and distributed on a commercial basis." Silliman made and sold both Soda Water for "complaints of the stomach, to correct acidity and indigestion, and as a palliative..." as well to simply enjoy as an "article of luxury" and Ballston Water, so named for the Ballston Spa in Saratoga County, New York, known for its natural, supposedly healing mineral waters.

Because Silliman couldn't find containers to properly contain his carbonated waters, he started distributing them via soda fountains. He opened two pump rooms in 1809 in New York City, "elegant establishments that catered to an elite clientele," according to Collectors Weekley. His mistake was continuing to focus on the supposed health benefits of carbonated water as opposed to the "luxury" he hinted at in an earlier advertisement. Competitors "who had better business sense than Silliman set up their pump rooms like a spa: You came to drink your carbonated water, but you hung around reading the free books and conversing with other intelligent people," Funderberg notes. His own company failed but soda fountains were here to stay.

Are there drugs in this soda?

As in Europe, American pharmacies introduced the public to the carbonated concoctions that would eventually become known as soda. According to sodaparts.com, "as the local drugstore evolved into the central attraction in most American towns and neighborhoods, the pharmacist was integral in providing beverages that were part pharmacology and part refreshment." DrugStoreMuseum.com describes the "drug revolution" of the 1850s, which saw people going to their local drugstore to "procure a fountain drink to cure or aid some physical malady." At this point in history, cocaine was legal and often used medicinally for pain relief; pharmacists would include cocaine and caffeine in their preparations along with "bromides and various plant extracts." Cocaine and caffeine worked well on maladies such as headaches, but of course "rebound headaches would ensue and the patient would be back frequently for another drink to get rid of the pain."

Another popular addition to what would become soda arrived in the United States in the late 19th century. West African people had used kola nuts as stimulants for centuries, due to the fact that they contain natural stimulants caffeine and theobromine, per BBC Future. The medical company Burroughs Wellcome and Co advertised their use of kola nuts and coca leaves in their Forced March tablets, noting that the ingredients' "active principles" served to "allay hunger and prolong the power of endurance."

The miraculous herb and the brain tonic

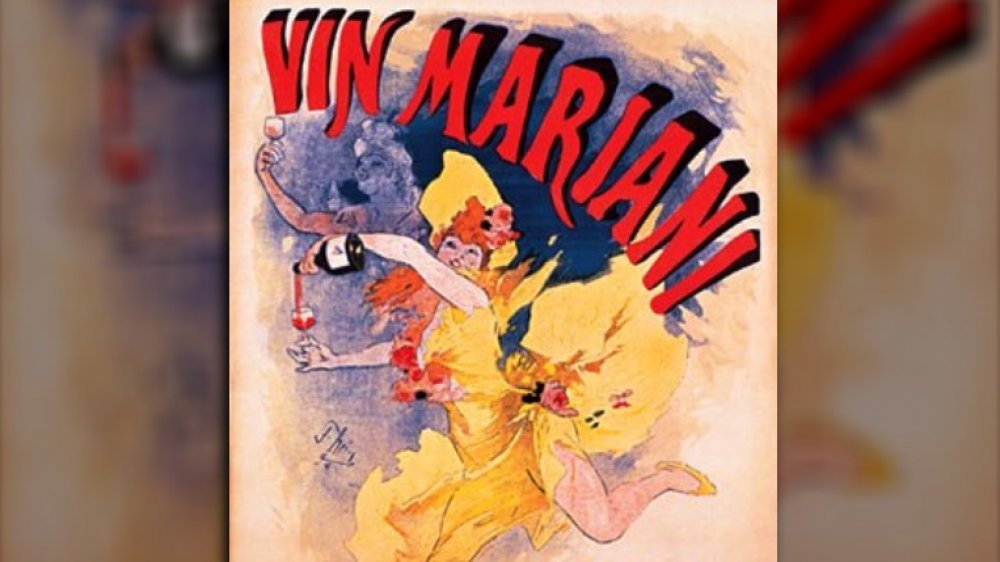

The soda industry as we know it today would not exist without the coca wine fad of the mid-1800s. According to The DrinksBusiness.com, Europeans became aware of the stimulating effects of coca leaves when explorers reached Peru and observed Peruvians chewing the leaves. Publications extolling the "miraculous herb" became available and people started experimenting with coca-infused concoctions. One of the more successful entrepreneurs was Corsican chemist Angelo Mariani, who developed "a mixture of coca and Bordeaux wine, fortified with brandy and sweetened." The alcohol worked to extract cocaine from the coca leaves; Vin Mariani was born and was an instant success, as "it delivered real effects, stimulating and overcoming exhaustion."

Exportation to the United States began and copies started cropping up, including one from Colonel James Pemberton, who had been injured in the Civil War and become addicted to morphine. Pemberton sought to "make a 'brain tonic' which would overcome the addiction and be a general stimulant." Combining coca leaves and wine with the caffeinating power of extract of kola nut, Pemberton debuted Pemberton's French Wine Coca in Columbus, Georgia in 1885.

Always Coca-Cola

Pemberton's French Wine Coca eventually came under attack from local authorities, but at that point, the cocaine wasn't the problem. Predating the United States' Prohibition of all alcohol in 1920, Georgia outlawed "the production, transportation, and sale of alcohol" in 1907, per GeorgiaEncyclopedia.org. Pemberton created a non-alcoholic syrup version of his tonic for use at drugstore fountains; in an apparent tribute to the two stimulants that gave the drink its kick, he named it Coca-Cola. According to TheDrinksBusiness.com, this original recipe contained "5 ounces of coca leaf per gallon," which is, well, a lot of cocaine. Pemberton later reduced the amount by 90 percent to account for the "growing public disapproval of cocaine."

Coca-Cola was first bottled in 1894, and cocaine was removed from the recipe by 1903. However, Coca-Cola still relies on coca leaves as part of its heavily-guarded secret recipe; Business Insider reported that the Coca-Cola Company has a special arrangement with the Drug Enforcement Administration that allows them to import coca leaves from Peru and Bolivia. The cocaine is removed from the leaves and used by another corporation to make cocaine hydrochloride, a legal topical anesthesia. Just like the Pemberton era, the (now cocaine-free) leaves are then added to the syrup that makes the world's most popular soft drink and keeps the Coca-Cola Company the most profitable beverage company in the world, per CaffeineInformer.com.

The oldest American sodas were blessedly cocaine-free

Not all historical sodas touted cocaine as some sort of miracle ingredient. According to LetsLookAgain.com, Irish chemist Thomas Joseph Cantrell is credited with creating and selling the first carbonated ginger ale in Belfast in 1852. In the United States, Detroit druggist James Vernor "first developed the recipe for his ginger ale, in an attempt to duplicate the flavor of the ginger ales from Ireland" at Higby & Sterns drugstore. Per SeriousEats.com, Vernor left ginger syrup in a cask when he left to fight in the Civil War. Upon his return in 1865, he discovered the syrup had improved in taste in his absence and started selling Vernors Ginger Ale, which still exists to this day and is thought to be America's oldest commercial soft drink.

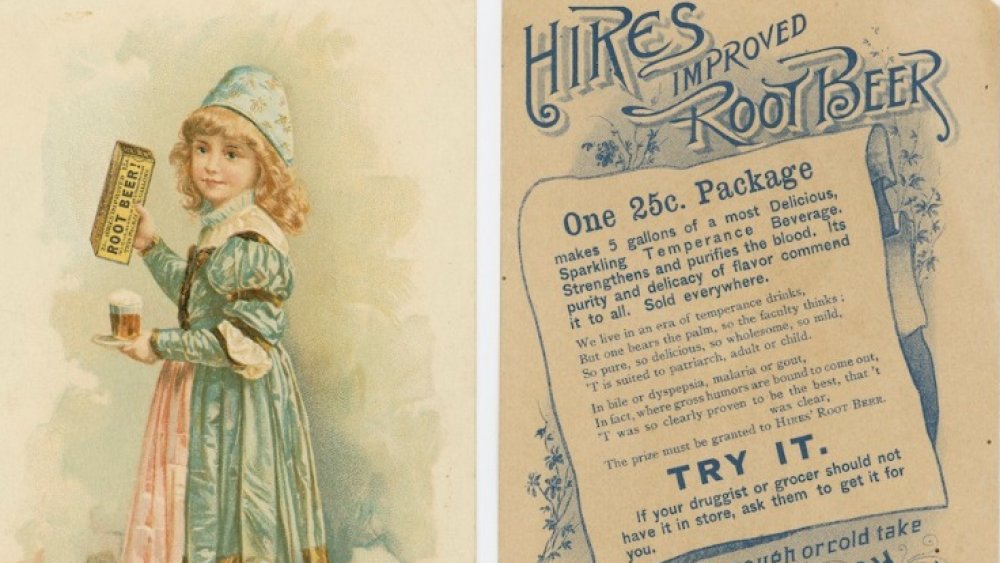

Nearly as old is Hires Root Beer, developed by Philadelphia pharmacist Charles Elmer Hires. According to ThoughtCo, the consumption of root beer "can be traced to pre-colonial times during which indigenous tribes commonly created beverages and medicinal remedies from sassafras roots." Stephanie Armijo's History of the Soda Fountain project notes that Hires tasted root beer on his honeymoon in 1875 and by 1876 had developed his own recipe for a root beer powder and gave away samples at Philadelphia's Centennial Exposition, claiming his drink would "purify the blood and make cheeks rosy." By 1884 he was shipping syrup to pharmacies and by 1890, he was selling bottled root beer, using tag lines such as "the Greatest Health-Giving Beverage in the World."

The creation of Moxie

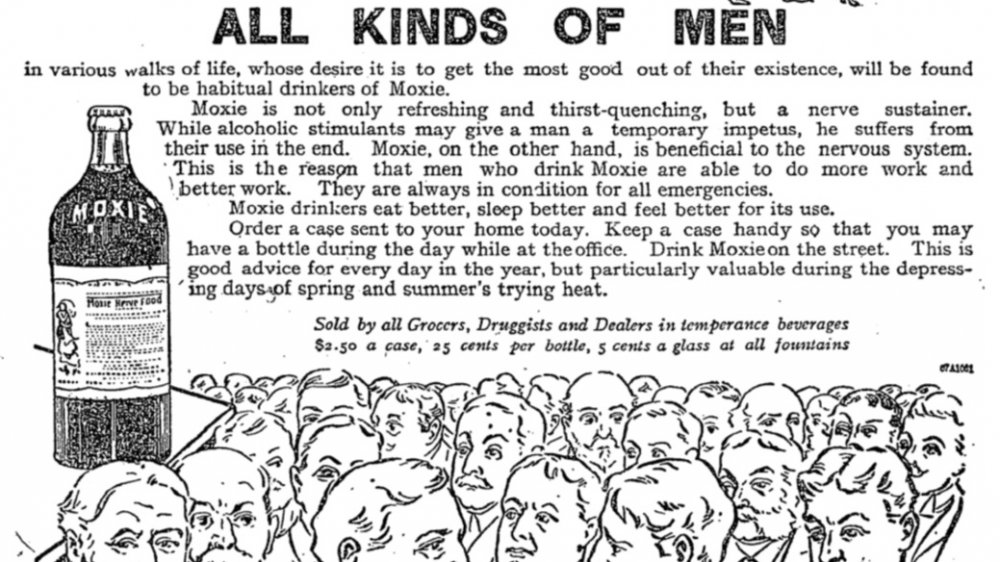

Another claim to old soda fame comes from Moxie, which, according to Matthews Museum of Maine Heritage, was invented by Dr. Augustin Thompson in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1884. With its first bottle sold in 1885, Moxie is, according to New England Moxie Congress president Merrill Lewis speaking to Take magazine, "the nation's oldest bottled soft drink." Like its fellow record-holding old soda brethren, Moxie was originally marketed as medicine. Its original name was "Moxie Nerve Food" and, per Matthews Museum, "was said to cure ailments ranging from 'softening of the brain' to 'loss of manhood.'"

According to New England Today, Moxie was once available in over 30 states and parts of Canada, but is now only found in New England; quite a fall for Moxie, since "by the early 1900s, [it]...was the nation's favorite soft drink, outselling modern-giant Coca-Cola." Perhaps it has something to do with its distinctive taste. New England Today calls it "a subtle, not-too-sweet blend of wintergreen and licorice, but others ... well ... they toss around words like medicine, motor oil, and 'root beer that's gone really funky.'" Nevertheless, Moxie still has a small but adoring public; it has been the official state drink of Maine since 2005!

Is Pepsi okay?

By the mid-1890s, the cola wars were underway. Pepsi started its long history of chasing Coca-Cola in 1893 when, according to PepsiStore.com, pharmacist Caleb Davis Bradham of Bradham's Drug Store mixed up "sugar, water, caramel, lemon oil, nutmeg, and other natural additives" to create "Brad's Drink," which was an "overnight sensation." In 1898, Bradham renamed his drink Pepsi-Cola, which, despite its name, never contained pepsin; the "Pepsi" was seemingly a reference to Bradham's belief that "the drink was more than a refreshment but a 'healthy' cola, aiding in digestion, getting its roots from the word dyspepsia, meaning indigestion."

Bradham formed and served as president of the Pepsi-Cola Company in 1902 "due to the rising popularity and demand for the Pepsi-Cola Syrup" and started selling a bottled version of Pepsi in 1910. Bradham fell on hard times when sugar prices soared during World War I. After failing to successfully replicate Pepsi's taste with substitutes such as molasses, "Bradham purchased a large quantity of the high priced sugar, which would be a factor to the company's downfall." On March 31, 1923, Craven Holden Corporation bought the Pepsi-Cola Company for $30,000; it survived, of course, and carries on to continue its rivalry with Coca-Cola year after year.

Dr Pepper enters the mix

Our last soda record holder is the self-proclaimed King of Beverages, Dr Pepper, which is purported by Medical Bag to be "the oldest major soft drink in America, having been created in 1885 by pharmacist Charles Alderton." Per the Dr Pepper Museum, Alderton was a pharmacist at Morrison's Old Corner Drug Store in Waco, Texas who "spent most of his time mixing up medicine for the people of Waco, but in his spare time he liked to serve carbonated drinks at the soda fountain." His inspiration for Dr Pepper's flavor was the drug store's odor from "all of the fruit syrup flavor smells mixing together in the air." Alderton's first taste tester was Morrison himself, who enjoyed it and began serving it to his customers.

The drink was first known as "a Waco"; Alderton renamed it "Dr. Pepper" for reasons lost to history. Medical Bag reports that the drink was "originally sold as an energy drink and a 'brain tonic,'" but the period in "Dr." was later "dropped in the 1950s for stylistic reasons as well as to eliminate any connotation of a medical link." The Dr Pepper Museum reports that in order to meet the demand for Dr Pepper syrup, "the Artesian Mfg. & Bottling Company, which later became Dr Pepper Company" formed in 1891. Like Hires Root Beer, Dr Pepper made its wide release debut at a fair, this time the 1904 World's Fair Exposition in St. Louis. Dr Pepper lives on today, perhaps paying tribute to Alderton's "all of the fruit syrup flavor smells" inspiration with its tagline "There's just more to it."