Upsetting Historical Facts You Wish You Hadn't Learned

Here's a fun game: if you could go back and live in any time period at all, when and where would you go? Would it be the freedom of the Wild West (and the tuberculosis), the excitement of the Victorian era (and the complete lack of health and safety regulations), or maybe the Middle Ages (and more disease than you can shake a stick at.)

History, it turns out, is full of dark, dirty, horrible stuff.

And it's kind of a shame we don't learn more about the grisly parts of human history, because when we talk about our ancestors, it's stuff they had to live through. Some things were voluntary, some ... not so voluntary. But it's all part of the human experience, and there's nothing that'll change your opinion of some of the greatest scientists in the world like the fact that alongside their great discoveries, they were probably eating people to cure their headaches. Do you want to know these things? Maybe not. Will you enjoy sharing these little tidbits at parties, and ruining everyone's night? Absolutely.

When people used to bathe inside dead whales

According to a news story published in 1896, via the Smithsonian, it started with a drunk guy. (Because of course it did.) He was on a beach with some friends when they spotted a rotting whale carcass and he — thinking he was hilarious — took a running start and dove right in. These were different times. His friends waited, and when he finally came out, he reported something strange: his rheumatoid arthritis was gone.

The Australian National Maritime Museum says that once the word got out, the town of Eden, Australia became a sort of a destination for arthritis sufferers, who would be lowered into a freshly dead whale through a hole, which would then be sewn up. If the person could stay inside for between 20 and 30 hours, they'd be cured! Or at least, they'd claim they were because no one wants to say they spent a day inside a dead whale for nothing.

It may have worked, because the rotting whale would have acted like a sweatbox, relieving some of the pain. Thankfully, there are other options today.

Hey, buddy... you're not going to need that skin when you're dead...

Witches, wizards, sorcerers ... they all have a bit of a bad reputation. Look at the rituals of 17th-century Icelandic magicians and, well, ya'll kind of deserve that rep.

Atlas Obscura says that Icelandic sorcery often called for some kind of bodily sacrifice: creating a tilberi (which was a two-headed snake-thing that would steal your neighbor's milk) required the rib of a corpse, for example.

And that's nothing compared to the nábrók, which translates awesomely to "necropants." In order to make a pair, it was said you needed to enter into an agreement with a still-living friend. When the friend (who had to be male, for reasons that will become apparent) died, they had to be buried, dug up, then skinned — carefully. The skin on the corpse's lower half had to be removed in a single piece with no tears, making some skin pants that would absolutely be worn. The sorcerer was then supposed to steal a single coin from a poor widow, put it in the scrotum of the pants, and eventually, the necropants would grow into the new wearer's body. The point of this? As long as the original coin remained, more coins would continue to appear. There's a reproduction of the pants at the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft — if anyone needs some nightmare fuel.

A funeral, a medical college, and a national scandal

You might not know John Scott Harrison, but you know his father — president William Henry Harrison — and his son, president Benjamin Harrison. You should probably also know John Scott's story because it caused a national scandal.

It started with his death on May 25, 1878. He was buried four days later, and Mental Floss says that's when attendees noticed that another grave — one belonging to Augustus Devin — had been emptied. After taking precautions to make sure their father wouldn't suffer the same fate (his brick-vaulted grave was covered with three slabs of stone and a layer of cement), they started looking for Devin's body. The suspect? The Medical College of Ohio, because anatomy colleges needed to get their subjects from somewhere.

They first found a student "chipping away" at the head of a Black woman, and nearby was the body of a 6-month-old baby. But... no Devin. They kept looking, and Harrison noticed a hole, a shaft, and a winch that looked suspiciously like something that might be used to move a body. He pulled on the rope and a body did, indeed, emerge from the darkness. Pulling aside the shroud, he found himself face-to-face with his own father.

The Medical College apologized for stealing the body of such an upstanding citizen. It was necessary, they said: no one wanted doctors practicing on living people, did they? Still, the Harrison family succeeded in getting legislation passed raising the penalties for grave-robbing.

The practice of corpse medicine

Here's a historical fact that'll make anyone grateful for modern medicine: early medicines were sometimes taken from dead people.

For hundreds of years — and reaching a high point toward the end of the Renaissance — European medicine involved a bit of cannibalism. The reasoning behind it was fairly straightforward: the more violent a person's death, the more surprised a spirit was. It would take that spirit a little while to shuffle off this mortal coil and in the meantime, body parts would have just enough life left in them to have healing powers.

Lapham's Quarterly says it goes back to ancient Rome when the blood of slain gladiators was thought to treat epilepsy — a belief that stayed well into the 17th century. Drinking blood was also prescribed for elderly people who needed a pick-me-up (as long as it was blood from an adolescent), and if drinking it isn't your thing, there were also recipes for blood jam out there.

Once Europe started stealing Egypt's mummies, ground mummy started becoming popular for mixing in wound ointments. Not gross enough? Powdered skull was used as a cure-all but was specifically used for stomach issues, while human fat was rubbed on the body to cure gout, and powdered then eaten by anyone who bruised or bled easily. All these body parts and fluids were readily available at apothecaries, or right from the executioner.

The tragic fate of the other couple in the box

Artistic depictions of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln often show another couple who was sitting in the theater with them. Ever wonder what happened to them?

They were Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris. They met the President and First Lady outside the theater, showed up fashionably late, and when John Wilkes Booth burst in and shot Lincoln, Rathbone lunged for him. They wrestled, Rathbone was stabbed, and Booth broke free to make his infamous leap onto the stage. Everyone knows what happened next.

In the following weeks, Clara Harris made an attempt to move on: Emerging Civil War says that one of the ways she did it was by posing for photos in her still blood-stained dress. But Rathbone? For the next seventeen years, he was plagued by chronic illnesses. Depression was constant, and reports say his behavior grew more and more erratic. He and Clara married and had children, but he became convinced they were all going to leave him.

Things came to a head on Christmas Eve of 1883. That's when Rathbone picked up a knife and a revolver, followed Clara into their room, shot her, and stabbed her until she was dead. He then tried to kill himself. He survived, though, and was declared insane. Rathbone was never prosecuted: instead, he was sent to the Provincial Insane Asylum, where he died in 1911.

It's possible to mummify yourself

Self-mummification: at least 24 people have done it, and according to io9, they were the practitioners of a sect of Buddhism called Shingon. Most died between the 12th and 20th centuries, but it's also thought that they're not the only ones who have undergone the process.

First, why? It's done by the most devout, and it's sort of a final demonstration of their unwavering spirituality. Some believed it was a path to immortality, while others saw it not as dying, but entering another state — from which they would eventually be called back. Having their earthly form intact would allow them to return when they were needed, to help those who called on them. And that's pretty noble.

Now, how was it done? There was a 3,000-day process that started with changing the diet to remove moisture, prevent bacterial growth, and improve chances of preservation, so that meant eating things like pine needles, resin, tree bark, and drinking a tea made from sap. Once the person was ready to take the final step, they would go into a small burial chamber, sit, chant, and ring a bell. There was a small opening for air, but once the bell stopped ringing, that meant the person was dead. The chamber would be sealed, and only opened three years later to see if it had worked. If it had, the person was removed, robed, and enshrined.

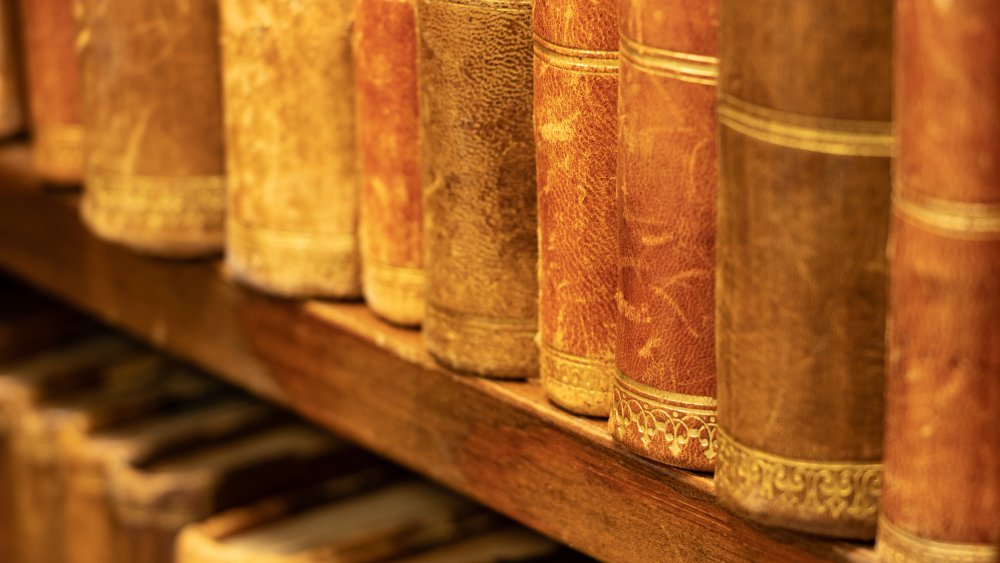

Yes, books have been bound in human skin

The BBC says that the practice of binding books in skin is officially called anthropodermic bibliopegy, and it's not as unusual as you might expect ... or hope.

It was particularly popular in the 19th century (but was done way, way before that), and that means some books come with a sad story. Take Harvard University's copy of Des Destinees de I'ame (or, Destinies of the Soul). That's definitely bound in human skin, and they're pretty sure the original owner of the skin was a female patient in an asylum.

Then, there are books like the one owned by the Bristol Record Office. That's made from the skin of John Horwood, who was 18 years old when he was hanged for killing Eliza Balsum. The book is actually about his crime, and after he was publicly dissected, it was decided to use his skin as bookbinding. The same thing happened with the infamous graverobber William Burke: his skin went missing first, then turned up as the binding of a little pocketbook.

So ... why would this be done? According to Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris of the Wellcome Trust (via Vice), part of the reason is that it's sort of an extra level of punishment. She also says that a number of books were bound with tattooed skin, and it was a way of making a decorative collector's piece. And lastly, to memorialize the person the skin came from. Sure, a photo might be easier, but people are weird.

You've changed ... and I hardly know you anymore

The original fairies of mythology were, well, total jerks. They were evil, demonic things, and they were even known for stealing human children and leaving something unspeakable in their place.

Across Europe, there was an old belief in changelings: creatures that were left in place of the children stolen by the fairies. Blond, blue-eyed boys were a particular target, and here's where it gets worse. Once parents identified their child as a changeling imposter, they would do all sorts of things to get the fairies to come and save it. Exorcisms, beatings, leaving them in the freezing cold, dunking them in rivers, or even giving them poison. According to Richard Sugg of the University of Durham (via Long Reads), there are Victorian records of changelings thrown or made to stand on hot coals, drowned, burned with irons, and outright abandoned.

It was all done in hopes that their "real" child would be brought back, but more often, they died. What was it that made parents suspect their child had been replaced by a changeling? When a healthy baby suddenly got sick, it was a changeling. Any physical or developmental deformities — especially those that only manifested well after birth — were seen as signs of fairy interference. And any behavioral changes — like a baby getting suddenly loud or troublesome — ran the risk of being deemed a changeling, and dealt with as such.

The Civil War kicked off with a picnic?

We now think of the 1861 Battle of Bull Run as the gory beginning of the Civil War. At the time, though, the Smithsonian says that most people thought it was going to be relatively quick. That, they say, is why so many wanted to see the Battle of Bull Run and get a glimpse of the fighting while they could. Contemporary newspapers would write that countless, hoity-toity folks got dressed in their Sunday best and headed out with picnic baskets to watch the festivities and bloodshed — which couldn't have happened, could it?

First, the biggie: yes, there were spectators and yes, they brought food with them, but Jim Burgess of the American Battlefield Trust says that was a necessity — some had traveled a long way, and it's not like there was a nearby McDonald's. And many were being completely realistic, knowing that they were wading into enemy territory.

War correspondents watching from a distance found themselves alongside ladies and gentlemen of all sides, with the London Times reporter, in particular, relaying the story of one woman who watched through opera glasses and squealed with delight at particularly bloody incidents unfolded before her.

Things really got up close and personal when the Union troops started to retreat, right through the lookie-loos. There was just one civilian casualty. She was an elderly widow named Judith Henry, who died when her house caught fire.

When schools required nude photos

For decades, posing in the buff was actually required for students enrolling in Ivy League schools. It all came to light in the late 1970s, when a Yale employee opened a long-locked room and discovered thousands of inappropriate photos. Those photos were burned, but word got out and The New York Times investigated.

What they found was that students from the 1940s to 1960s were required to submit to "posture photos," which were clothes-free photos taken from every angle of subjects with pins attached to their spines. Turns out, there was a lot of dark stuff behind it.

The NYT investigation found that for starters, the photos were used in studies like one done at Wellesley and financed by big tobacco. That one used photos of Harvard students and discovered that the more "manly" students smoked more. (Harvard, it was noted, had been taking these strange photos since the 1880s). Others were used in books, as illustrations in titles like the Atlas of Men.

It gets weirder: One Yale professor came forward with the information that the photos were actually "anthropological research," materials requested by researchers who wanted to study the connection between a student's body type and their intelligence. Sound Nazi-ish? Some thought the goal was to support the very questionable field of eugenics.

Appeasing the weather any way they could

Starting in 2011, archaeologists excavating an area in Peru called Huanchaquito got much more than they bargained for: the skeletons of hundreds of children, all between the ages of four and 14. Head archaeologist Feren Castillo described it like this (via The Guardian): "This is the biggest site where the remains of sacrificed children have been found. There isn't another like it anywhere in the world."

The sacrifices — 227 of them, who were all facing the sea when they were found — were a part of the Chimu civilization, died between 1200 and 1400, and evidence suggests they were executed where they were discovered. Footprints were preserved in the site, too, including small ones that suggest they were marched to the site.

That site was discovered by accident, and after years of digging and documenting, archaeologists think they sort of know what was going on. Children — along with llamas — were sporting the cut marks of ritual sacrifice and were buried in mud. That mud led archaeologists to suspect they were killed in an attempt to appease the gods and bring an end to a chaotic, rainy weather pattern that still exists. We call it El Niño.

The Magdalene laundries: punishment for profit

Between 1922 and 1996, orders of Roman Catholic nuns operated Magdalene laundries in Ireland, and in those decades, at least 10,000 women were sent there to pay a penance for their crime: they were unwed and pregnant. Some were sex workers, others were the victims of assault. Others were sent there not because they were pregnant, but because they were orphans, or simply abandoned by their parents.

It wasn't until 2018 that The New York Times was starting to report on the women who'd lived through the system of orphanages and workhouses who were coming together to try to find each other. And it's no wonder many tried to forget about it: they were put to work in "industrial schools" and told that their hard labor — with no pay, educational opportunities, or medical support — was penance for their sins.

More information has come out about the Magdalene laundries and the horrors that went on there. At the very forefront was a shocking discovery in the small town of Tuam, which was the location of the St. Mary's Mother and Baby Home, a "way station" for unwed mothers and their children. New mothers did a year of labor as penance, then left — usually, without their children. And what happened to the children? Some were adopted. But the remains of 796 of them were discovered in 2012, buried in the home's old sewage area.