The Crazy Truth About The Time When There Were Three Popes

The Western Schism, also known as the Great Western Schism to distinguish it from the Great Schism of 1054, refers to one out of many crazy moments in the history of Christianity. In this case, there were as many as three popes simultaneously. While two of those popes are now referred to as antipopes due to their illegitimacy in the line of papal succession, at the time, each of the popes and their respective successors had their own followings.

Lasting almost 40 years between 1378 to 1417, the multiple popes rebuked and excommunicated one another repeatedly and tried to stake their claim to the papal throne in the hopes that the other would simply go away. Meanwhile, those who followed either pope had to worry about whether or not they were going to get excommunicated as well and lose all chance at eternal salvation.

In the end, the Church had to step in with their own council of cardinals and bishops to decide once and for all who was going to be pope. And even that took more than one attempt. This is the crazy truth about the time when there were three popes.

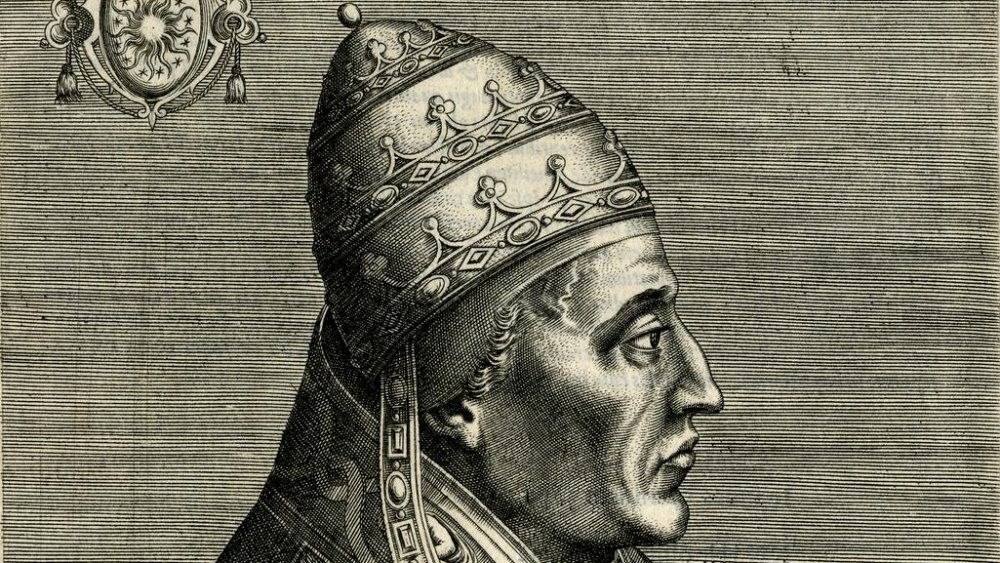

The background of Boniface VIII

The story of the Western Schism begins almost 100 years earlier in 1294, when Boniface VIII succeeded Celestine V as pope. According to Our Sunday Visitor, Boniface wanted to revive the Church's hegemony over secular matters in addition to spiritual ones. Boniface hoped to recreate the papacy in the image of what it had been under Pope Innocent III, who ruled from 1198 to 1216. According to The Age of Schism by Herbert Bruce, just as Innocent had claimed that Peter had been commanded to rule not just the Church but the whole world, Boniface insisted that "all men were subject to the Pope."

The Church also claimed not to be subject to the laws of man. Thus, it was infuriating to the pope when the French king Philip IV decided to impose taxes on church property. Boniface contended that the king had no right to demand taxes from the Church, and in 1296, he issued his own papal bull, Clericis laicos, which forbade the collection of taxes from clergymen unless there was specific permission from the pope, under the threat of excommunication.

The feud between Boniface and Philip escalated over the years. Eventually, Philip escalated it to another level when he authorized Boniface's kidnapping on September 3, 1303. The kidnappers unsuccessfully tried to beat Boniface into resigning, and although he was rescued from his captors, within a month, he was dead.

The Avignon papacy

With Boniface VIII out of the way, Philip IV openly exerted his influence over the new popes. After Boniface, Blessed Benedict XI ruled briefly for a year, but it's suspected that he was poisoned when he refused to pardon those who led the attack on Boniface. According to "The Avignon Papacy" by Lynn Harry Nelson, the corruption of the papal administration in Rome was notable at this time, and many were actively resisting papal rule. Nobles refused to send revenues or military service, and there were recurring mass riots within Rome.

So when Clement V was elected, Philip's influence was apparent, and, according to ThoughtCo, the new pope's election was an incredibly unpopular decision within Rome. In response, Philip suggested that Clement move the papal court to a less oppressive environment. Clement was incredibly amenable to the suggestion and proceeded to move the papal court to Avignon in 1309. The Avignon Papacy lasted until 1377, during which time all the popes were French, seven in all, as were 111 out of the 134 cardinals created during that time.

During this time, the papal court was thought to be a puppet in the hands of the French kings, but the Avignon popes weren't as much under their control as the kings would've liked. However, this perception contributed to the declining reputation of the papacy, which especially suffered during the Black Death due to its inability to provide sacraments to all the dying people.

Gregory XI brings the papacy back to Rome

Also known as the Babylonian Captivity, the Avignon Papacy was a time of greed and corruption and led to a decline in the papacy's credibility. St. Bridget of Sweden and Catherine of Siena were instrumental in persuading Pope Gregory XI to return the papal court to Rome. According to Papal Artifacts, St. Bridget warned Gregory of his dependence on political alliances, while Catherine of Siena spoke to him as "an ambassador of peace."

According to The Great Schism, the city was in a state of turbulence when Gregory returned to Rome on January 17, 1377. Dismayed to find Rome in as much of a state of turmoil as it had been when the papacy left, Gregory resolved to return to Avignon. However, before he could make the trip back to Avignon, he died on March 27, 1378. According to If:Gathering, at the prospect of a papal election, riots broke out in Rome as citizens worried that the next pope would be another Frenchman who'd move the papacy back to Avignon.

O April 8, 1378, 16 cardinals of the conclave elected the Italian archbishop Bari Bartolommeo Prignano to the papal throne. But before they could let him know, a mob of Roman citizens broke into the Vatican palace, continuing to demand the papal election of an Italian. The cardinals fled, and Prignano wasn't notified of his new position until the following day.

Plotting to remain

Ultimately, the cardinals had also wanted to ensure that power remained centralized within Rome, so they had intentionally chosen the Italian Bartolommeo Prignano as Gregory XI's successor. Prignano took the name Urban VI and, unfortunately for the cardinals, began a hostile rule against them, many of whom were still of the French legacy.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, during the years at Avignon, the cardinals had become used to assuming a great majority of power, and while they hoped to continue in this trend under Urban, the new pope had different plans. Urban wanted to reform the Church himself and harshly criticized the cardinals for their idleness and obsession with luxury.

One by one, the cardinals who opposed Urban abandoned Rome or turned against him. On August 2, 1378, 13 French cardinals fled to Anagni and published a manifesto in which they declared Urban's election to have been null and void. Although they declared Urban's election to have been illegitimate at the time, his legitimacy has ultimately been confirmed and is no longer contested. The cardinals claimed to have been under pressure from the Roman populace and elected a new pope on September 20. According to Lapham's Quarterly, the cardinals elected Clement VII, known as the first antipope, who soon returned the papacy to Avignon.

One pope, two pope, red pope, blue pope

After the cardinals denounced Urban VI as an opportunistic usurper and elected Pope Clement VII, the Church was officially split. According to The Great Schism, the two men swiftly excommunicated one another with the hopes of driving the other out of Rome. But Urban refused to be the one to leave Rome, and since Clement VII was already supported by the French king, Clement decided to move the papal court back to Avignon and returned there in June 1379.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, this schism resulted in divisions primarily across national lines. While rulers from France, Scotland, and Aragon supported the Avignon papacy, England, Hungary, and the Holy Roman Empire supported the Roman papacy. As a result, the antagonism between followers of the two popes mirrored and fostered the political antagonisms of this era. In most regions, the populace followed the lead of their ruler and were devoted to whichever pope their king or queen deemed to be legitimate.

However, this schism caused issues when it came to the eternal salvation of the masses. According to "The Great Schism, 1378-1415" by Lynn Harry Nelson, when the two popes declared that anyone accepting sacraments from a heretical clergy would be excommunicated, it meant that half of Europe was doomed to eternal damnation. And apparently the true pope, whoever it was, was unable, or unwilling, to save them.

A history of the antipope

Clement VII wasn't the first antipope in the history of the papacy. According to Papal Artifacts, one of the first antipopes was St. Hippolytus, though he eventually reconciled with the Church, which is why he's consecrated as a saint.

While the Western Schism is likely one of the most famous occasions of there being eventually not one but two simultaneous antipopes, there were many antipopes throughout history. According to Learn Religions, the term "antipope" refers to any person who claims to be pope but whose claim is considered illegitimate by the Roman Catholic Church.

And despite the fact that the Vatican keeps an official list of popes called the Annuario Pontificio, there are still at least four instances where there's uncertainty as to whether or not someone was legitimate in their succession of Peter. For example, those who succeeded Benedict IX in 1044 can perhaps be considered antipopes since it's unclear if Benedict's forcible removal from the papal throne was legitimate. And while Benedict was able to take back power in 1045, he was removed again and this time tendered his resignation as well. But then after being succeeded by Gregory VI and Clement II, Benedict once more returned to the papal throne before being ejected for the third, and final, time. And although the Annuario Pontificio lists Benedict's successors as legitimate popes, it's unclear if any of his removals were canonically valid.

The schism persists

After Urban VI and Clement VII, the two papal capitals continued to elect their own popes and maintain their own papal courts. According to The Great Schism, after Urban's death in 1389, the Roman cardinals were ultimately the first ones who decided to elect Boniface IX rather than rectifying the schism by recognizing Clement VII. After that, the Avignon cardinals followed suit and elected Benedict XIII to their own papal throne.

The rival popes continued to repeatedly denounce each other, which resulted in a severe loss of credibility for the papacy. According to "The Great Schism, 1378-1415" by Lynn Harry Nelson, people who were considered as close to saints as humanly possible (minus the dying part) were consulted about the legitimacy of the popes. But unfortunately, neither pope had a clear majority of favor, and people were distraught at the lack of leadership.

Many called for the Church to revive apostolic poverty, while others argued that maybe the sacraments were merely ritualistic and not essential to the Church's existence. Many others embraced more mystical movements, a majority of which placed the power of the Church into the hands of individuals, a precursor to the upcoming Protestant Reformation.

Papal lines of succession

For several years, the Rome and Avignon chapters continued to elect their own popes who, despite claiming to want to work toward reunification, never made any actual attempts toward such an endeavor. And with each papacy continuing to elect new popes, there existed two lines of papal succession whose legitimacy was debatable. According to The Philosophy of the History of the Church by Jacob Ditzler, the University of Paris was particularly involved in trying to reconcile the schism. There were many renowned theologians at the university, and they were incredibly invested in ending the schism.

According to the University of Oregon, the University of Paris offered three solutions. Either both popes could resign, an independent tribunal could judge the dispute, or a general council of the Church would be the final authority. But neither pope agreed to submit to these options.

In 1407, there was a brief moment when it seemed like the two popes had found a way to reconcile. The Roman popes Innocent VII and his successor Gregory XII had both intimated that they were interested in a papal reunion, so it seemed finally possible. An agreement was made in which both Gregory XII and Benedict XIII of Avignon were to simultaneously resign. Unfortunately, since neither one trusted the other, they both refused to resign, and the schism persisted in its stalemate.

How many popes is too many popes?

In 1409, cardinals from both lines of papal succession decided that enough was enough and convened on their own in an attempt to end the schism. According to the University of Oregon, the cardinals took up the suggestion from the University of Paris to put together a general council, and so they convened the Council of Pisa.

According to The Great Schism, the general council of ecclesiastical dignitaries and theological experts met on March 28, 1409, but neither pontiff accepted the invitation. The two popes tried to call councils of their own, but almost 500 people attended the assembly at Pisa. In effect, the Council of Pisa declared the two existing popes to be illegitimate and elected a third, new pope who took on the name Alexander V. Unfortunately, since neither existing pope recognized the authority of the general council, both Gregory XII and Benedict XIII of Avignon refused to resign, resulting in the existence of three separate popes.

Despite the fact that most of Europe recognized the legitimacy of Alexander V, his election still didn't resolve the schism, and there would continue to be three different popes until Gregory XII's resignation in 1415. After the death of Alexander V, the Council of Pisa elected his successor John XXIII, establishing three concurrent lines of papal succession while all three popes continued to excommunicate one another.

Coming to an arrangement

The schism finally ended up being somewhat resolved at the Council of Constance in Germany in 1414. According to The Great Schism, John XXIII convened the council on November 5 with the intention of allowing all nations to vote for a new pope. But in March 1415, realizing that the council wasn't planning on confirming him as the one true pope, John XXIII fled Constance with the hope that the council would simply dissolve itself.

However, enough was enough at this point, and Emperor Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire intervened in order to convince the cardinals to remain and work toward a reconciliation. On April 6, 1415, the Council of Constance decreed that they represented the universal will of all Christians and that everyone, including the pope, was subject to their decision. With their legitimacy established, the council proceeded to depose John XXIII on May 29, and by July 4, Gregory XII had also abdicated.

Benedict XIII of Avignon refused to step down and instead had to be once more excommunicated, although he held onto his claim of papacy until his death. But in November 1417, after the Council of Constance elected Martin V as the one true pope, every nation except for Scotland recognized his legitimacy.

The Western Schism winds down

After Martin V was elected, the Western Schism started winding down. Considering the chaos that had occurred during the schism, Martin V knew that he had to restore the legitimacy of not only the papacy but the entire Church as well, so he restored the papal capital officially to Rome.

However, the Avignon papacy persisted in their rejection of him, and after the death of Benedict XIII, the Avignon cardinals chose Clement VIII as his successor. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, there was some dispute over the papal succession in Avignon as well. After the death of Benedict XIII, one of his cardinals who hadn't been invited to the conclave to decide the next pope decided to hold his own and elected Benedict XIV on November 12, 1425. Essentially, there was briefly an additional antipope countering a preexisting antipope.

According to the National Catholic Reporter, Clement VIII finally renounced his claim to the papal throne in 1429 and accepted the reign of Martin V along with the few cardinals who remained in his camp. Meanwhile, Benedict XIV ended his rule in 1430 and, having conducted his reign so secretly, became known as the "hidden pope."

The legacy of the Western Schism

The drama between the various popes did a great deal of damage to the legitimacy of the papacy. According to The Great Schism, conciliar theory and the use of a general council rather than dependence on the pope developed during this time in direct response to the failure of papal leadership, especially once people saw that a general council was able to reconcile the Church in ways that the pontiffs were blatantly unwilling to consider.

According to Our Sunday Visitor, people were also simply able to learn how to live without knowledge of the true pontiff, which furthered the notion of individualism that propelled the propagation of the Protestant Reformation. In some places in Europe, hostility toward the papacy also began to grow. Despite the fact that the Catholic Church ultimately survived the schism, their credibility was irrevocably damaged.

According to Lapham's Quarterly, the corruption and extravagance of the papal courts had been laid bare and offered ample examples to clerics and philosophers who were calling for a radical reform of Christianity. Tensions continued to build for almost 100 more years until they came to a head on October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses.