Why Paul Revere's Midnight Ride Didn't Actually Happen

Everyone knows the story. Paul Revere rode at midnight from Boston, Massachusetts, yelling, "the British are coming!" His warning helped the revolutionaries prepare for the upcoming skirmishes against the British. But Revere's midnight ride, and the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem it inspired, didn't happen as many believe. Longfellow's poem describes Revere seeing a signal that the British army was coming by sea, so he saddles up his horse and rides like the devil, shouting and ringing a bell to warn everyone throughout Middlesex County. In reality, Revere didn't complete the whole ride, wrote Smithsonian Magazine. Nor was he the only rider.

He was, however, a real person. According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, he was a silversmith and an engraver, as well as an American revolutionary. His father, Apollos Rivoire, was a French refugee who had come to the United States as a child. Revere received schooling and followed his father into metal works. He focused not just on making things with silver; he also made surgical supplies, crafted eyeglasses, and famously created a copper plate etching depiction of the Boston Massacre.

Revere always had a deep sense of duty to his country and freedom. As PBS reports, Revere volunteered to join the British army in 1756 to fight the French, where his family is originally from. He was a member of the Sons of Liberty, and allowed the printing of Revolutionary propaganda in his workshop. Revere was also involved in the Boston Tea Party, helping dump tea into the harbor.

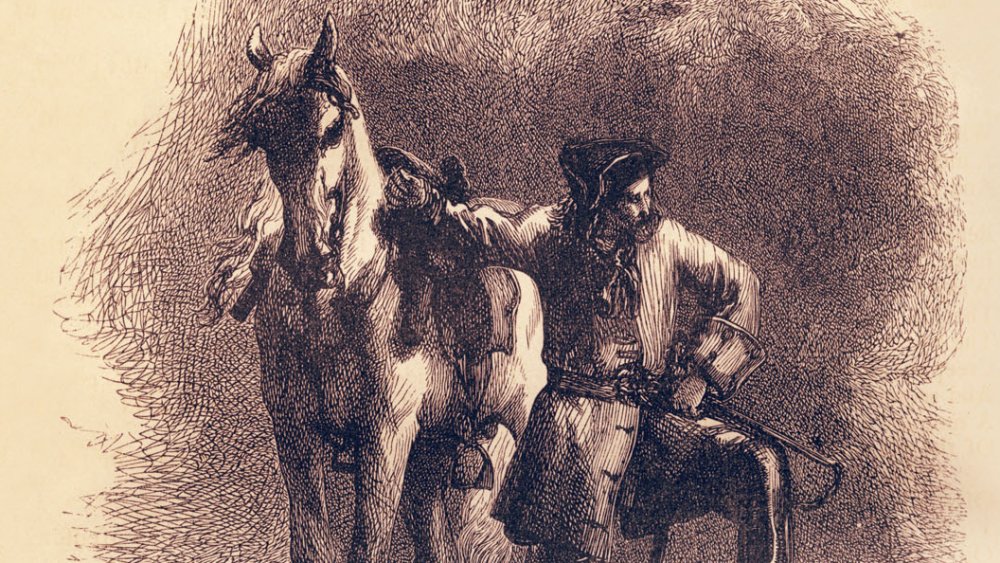

Engraver, silversmith, and revolutionary

During the Revolutionary War, Revere worked to bring intelligence information to American freedom fighters. It is this work that laid the groundwork for what would be his most famous act.

According to Biography, Revere was asked to meet with Joseph Warren, one of the few remaining Revolutionary leaders in Boston, on April 18, 1775. Warren informed Revere that British troops were making their way to Concord to destroy military garrisons in the area and perhaps arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock. To get word to both Adams and Hancock, Warren asked Revere to go to Lexington. Warren also told Revere that another messenger had also been dispatched.

Revere started his ride, not by waiting for a signal from a friend, but because he was ordered to do so. By Revere's accounts, reports Biography, he asked a friend to bring lanterns into the Old North Church to signal other revolutionaries that the British were either coming by land or sea. Unlike the poem, it was Revere who ordered the signals. Revere then began to ride toward Lexington. But first, he met up with other conspirators who rowed him across the Charles River. He borrowed a horse, then made his way to Adams and Hancock. Smithsonian Magazine explains that Revere dodged several British troops while riding toward Lexington, so he changed his route and arrived around midnight. Once he reached the house where Adams and Hancock were staying, he made some noise.

He didn't even make it to Concord

By the time Revere reached Lexington, the house was asleep, Smithsonian Magazine said. He fought with a guard outside the home where Hancock and Adams stayed, who told him to keep the noise down. He said, "Noise! You'll have noise enough before long! The regulars are coming out!" The ruckus awakened Hancock, who invited him in. Before long, Dawes, the other rider Warren dispatched, arrived. Together, Revere and Dawes prepared to ride to Concord in hopes of warning people about the British troops marching toward them and making sure the military supplies were safe. On the way, they met another rider named Samuel Prescott, who agreed to help spread the word about the British. While the three were riding, it was Prescott and Dawes who would awaken houses to warn them as Revere pushed forward as an advance party.

Biography wrote that Revere noticed some British soldiers and warned the other two riders. Dawes and Prescott were able to escape, but Revere was captured. The British released him soon after, but without his horse. Revere walked back to Lexington to help Adams and Hancock escape. In the end, it was only Prescott who managed to make it all the way to Concord.

Why is Revere the only one mentioned by Longfellow? Smithsonian Magazine posits it's because he was the most politically active of the three. The famous person gets the glory, and generations of children learn an historically inaccurate poem.