The Untold Truth Of Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer started her life as the 20th child of Mississippi sharecroppers and ended it as a leader and a hero for civil and voting rights. According to the National Women's History Museum, she was born in poverty in 1917, started picking cotton alongside her family at the age of six, and was forced to leave school when she was 12 in order to work full time. In 1944, she married Perry "Pap" Hamer. Together they worked on a plantation owned by B.D. Marlowe. Hamer was unique — she was literate — and so also functioned as the plantation's timekeeper. BlackPast reports that Hamer became an activist in the 1950s after she attended several of the annual conferences of an organization called the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. There she encountered Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP, who in 1967 became the first Black Supreme Court justice, and Michigan Congressman Charles Diggs.

According to PBS American Experience, in 1961, a white doctor performed a hysterectomy on Hamer without her knowledge or permission during unrelated minor surgery, a notorious practice inflicted upon Black women so often that it was known as a "Mississippi appendectomy." In 1964, Hamer told a Washington D.C. audience that "[In] the North Sunflower County Hospital, I would say about six out of the 10 Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with the tubes tied." PBS says the tragedy propelled Hamer on her way to "the forefront of the Mississippi Civil Rights movement."

'This Little Light of Mine'

The Hamers adopted two daughters.

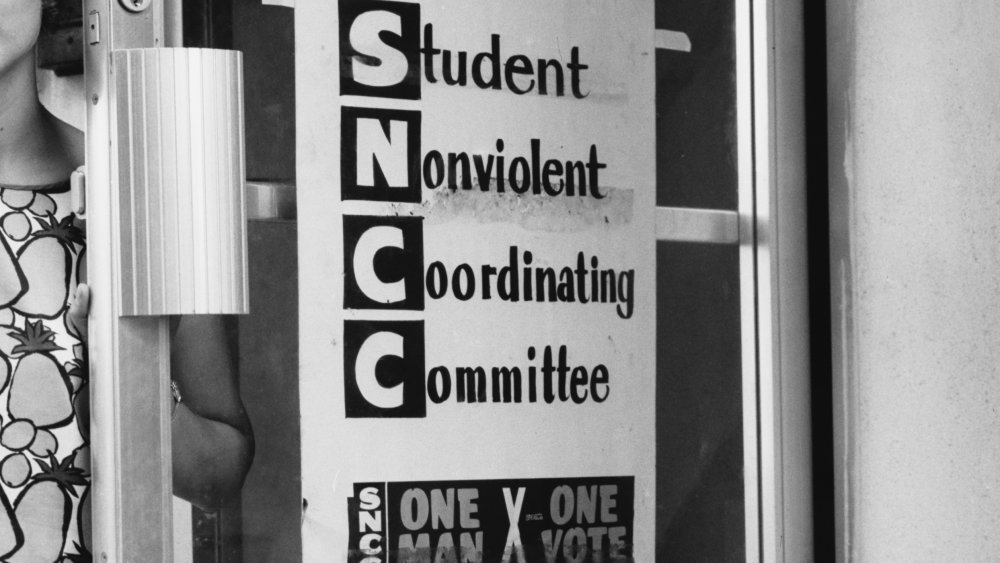

In 1962, per BlackPast, Fannie Lou Hamer heard a sermon by Reverend James Bevel, an advisor to Martin Luther King, Jr., and was inspired to volunteer, serving as an organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, helping register Black Mississippians to vote. In August 1962, Hamer and 17 neighbors took a bus to the county seat in Indianola to register; according to PBS, officials kept everyone but Hamer and one man from filling out the application and taking the required literacy test. They both failed. On the way home, officials stopped the bus for "being too yellow"; Hamer "began to sing spirituals" such as "This Little Light of Mine," which became "became one of the defining features of her activism." When she returned home, the plantation owner Marlow "demanded that she withdraw her application" to vote. When Hamer refused, he kicked her off his land.

In 1963 Hamer and other organizers were once again traveling by bus, relates BlackPast, when they were arrested in Winona, Mississippi and taken to the infamous Montgomery County Jail, where they were "beaten mercilessly." Hamer suffered a blood clot and kidney damage that affected her for the rest of her life. After recovering for a month, she returned to organizing. In 1964, she co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, as Mississippi's Democratic Party prohibited Blacks from participating.

"I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired"

Leaders of that Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) made their way to Atlantic City, New Jersey, site of the Democratic National Convention, to argue that they should be "the official delegation from Mississippi." There, Hamer spoke before the Credentials Committee, decrying the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party delegation, an action that scared President Lyndon Johnson so much that he "gave an emergency presidential press conference to prevent her testimony from going live over the three television networks." Her speech, which aired later, told listeners about the "oppressive conditions" faced daily by Black Mississippians. Hamer urged recognition of the MFDP "to encourage Blacks to register to vote."

In early 1964, reports PBS, Hamer ran for congress as the MFDP candidate, setting a precedent. Her opponent won, but Hamer's candidacy had challenged entrenched Mississippi politics and brought national attention to the MFDP. In June 1964, Hamer became "a statewide leader in the Freedom Summer Campaign which brought hundreds of volunteers ... to Mississippi to help with voter registration." By 1968, she was part of the regular Mississippi delegation to the National Democratic Convention, where she spoke out against the Vietnam War. That was also the first year that the Democratic Party required equality of representation in state delegations, which surely came to be in part because of Hamer's 1964 testimony.

Fannie Lou Hamer died of cancer in 1977; her epitaph reads: "I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired."