What It Was Really Like To Be A Medieval Knight

We modern people like to sit in our climate-controlled homes with our big screen TVs and microwave popcorn and watch movies about medieval knights, and for some reason we think being a medieval knight would be cool. But we are wrong, oh so very wrong. Never mind the total absence of climate-controlled houses (newsflash: castles were drafty) and big screen TVs and microwave popcorn during the Middle Ages, because even if knights did have all those things it wouldn't change the fact that their lives sucked. Sure, there was a perk or two but for the most part it was grueling work, mortal peril, mortal peril, mortal peril, death. And the closest a medieval knight ever got to microwave popcorn was a pie made out of eels, so there's that.

You might be thinking the court ladies and the shiny armor and the giant horse still sounds pretty cool, though, and if you are then you may want to hold off on teleporting back through time to claim your title as Sir Whatever until after you've read about what it was really like to be a medieval knight.

Being a medieval knight wasn't exactly an equal opportunity job or anything

In the early days of the knighthood, a common person might attract the attention of a military commander by being especially brave or agile with a pitchfork. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, such a person could move up through the ranks and become a knight based on merit alone. Often, a noble or even the king himself would bestow the title of "knight" on the battlefield, after that individual proved himself with a lot of bloody impressive violence. That's where the expression "winning your spurs" came from, since new knights who got their title in that way were usually given a pair of spurs as a symbol of their new status.

Shockingly, this system didn't last, because it was super unfair to the spoiled sons of rich nobles. By the 13th century, the only way to become a knight was to have wealthy parents, but wait, there was an excellent reason for that. Because if you let just any commoner become a knight, then it would no longer be this cool exclusive thing that you earned by virtue of birth. See, told you it was an excellent reason.

Even so, being a medieval knight wasn't easy

Boys got to start training to become knights because their dads had money and status, but that doesn't mean they could just pick up an expensive costume at the Spirit Halloween store and then trick-or-treat, knighthood. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, knights started training somewhere between the ages of 7 and 10. That's right, at the age when most modern kids are still trying to get through a whole day without having a meltdown over the pickle they found in their McDonald's cheeseburger, the sons of medieval nobles were already practicing to become metal-clad killing machines.

For some kids, this was probably way cool. At first. For other kids, it was probably a lot less cool, because it's not like they got to choose between learning to be a knight or going to the local Waldorf school or something. Their parents decided early on what their future was going to look like, and they pretty much had to just go along with it even knowing it would be a life full of mortal peril. So take note, kids — your monstrous parents might take your iPad away from you at 6 pm, but at least they're not signing you up for violence and an early grave.

It was a long, long process

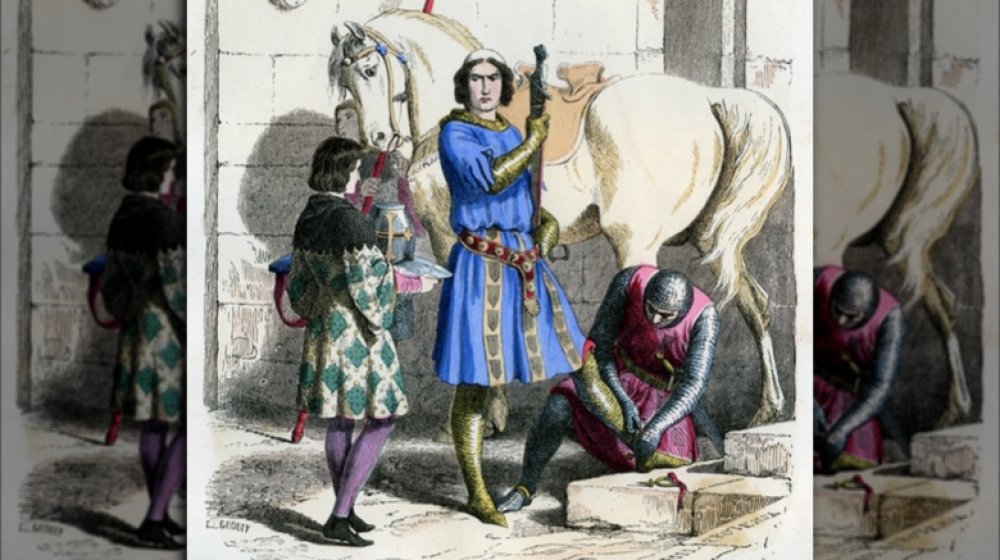

Don't worry, no one put a full suit of armor on a 7-year-old kid and then sent him into the melee on the back of a gigantic stallion or anything. According to Medieval Life, a boy whose parents had aspirations of him becoming a knight would start out as a page, which was basically just a medieval gofer. The page would work in the stables, serve food, pick up some Starbucks for the Round Table, and perform other super menial tasks while also learning to ride horses and handle a sword. After a few years of that, he would graduate to squire, usually around the age of 14.

Being a squire was, um, also kind of like a medieval gofer, only squires were placed in the service of a specific knight. A squire's job was to clean and polish weapons and armor, take care of the knight's horse, and help him put his pants on in the morning. Not really that last one, but the squire did have to make sure his knight was properly outfitted for battle.

If all went well, a squire would become a knight somewhere between the ages of 18 and 21. All didn't always go well, though. Some squires ended their careers without becoming knights (Geoffrey Chaucer is one famous example) and some just kept on being squires their whole lives, which sounds kind of embarrassing, but hey, at least there was a lot less mortal peril.

In between shoveling horse manure and wiping blood off swords, there was grueling training

You might be picturing kids out on the castle grounds with wooden swords learning how to fight, and if you are, well, that's cute. There probably was some of that, but training to become a knight was way, way more grueling than a little play fighting on the lawn.

According to Medieval Britain, once a page became a squire, he had to master "the seven points of agilities," which was really just a long list of sporting events: Shooting, fencing, wrestling, riding horses, swimming and diving, climbing, long jumping, tournament sports like jousting, and dancing. Okay so that's more than seven apparent points of agilities, and dancing was in there, so let's just agree that medieval logic was a bit strange and their math skills were bad and then we can move on.

But that's not all, squires also had to learn how to recite poetry, hunt, play chess, and impress the ladies, because you couldn't have uncivilized brutes running around court being all sweaty and offensive or anything. So there was not a lot of leisure time for these kids, some of whom probably got dubbed as knights and then died in battle like the following Tuesday.

Because God wants you to kill people, amen

How do you raise a kid to become a ruthless killer but also make sure that he behaves nicely at parties? You tell him he's doing God's work. That handily gets you past the whole "thou shalt not kill" thing, too.

For the most part, knights believed that their work was a holy calling, which made it easy to justify pretty much anything done in the name of the king, who was God's chosen ruler. And just to make sure that every knight understood just how cool God was with all the violence, the knighting ceremony (called "dubbing") was full of religious symbolism and ritual. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the squire was required to spend the night before his dubbing ceremony in prayer, and before he was officially dubbed, a priest would bless his sword and maybe stuff a religious relic or two inside the hilt.

It wasn't all about absolution and obedience to the king, though; it was also about killing infidels. By the 11th century, the religious aspect of knighthood also translated into knights serving the Church, which promised them they'd get a comfy spot in heaven if they traveled to the Holy Land and killed a bunch of not-Christians during the Crusades. Knowing they were a shoo-in for that eternal reward probably did make knights a lot braver, especially in a time when everyone believed that death was pretty much a toss-up between heaven and hell.

And you thought that bulky sweater that grandma knitted was oppressive

One thing that especially sucks about winter is the heavy coats that make it challenging to do things like walk normally or move your arms. Now imagine if you were covered from head to toe in metal and you also had to somehow be agile enough to swing a broadsword and, you know, duck.

The good news, according to Lords and Ladies, is that a knight's sword didn't weigh as much as Hollywood says it did. The average medieval sword only weighed around three to five pounds. That makes a lot of sense, actually, since a double-bladed weapon doesn't have to be especially heavy to be lethal, though it does have to be fairly easy to aim.

That suit of armor, though, was a beast. It weighed between 45 and 55 lbs. and included a helmet that weighed between four and eight pounds. That's not actually as bad as it sounds, though. The weight was pretty evenly distributed on the knight's body so mobility wasn't really a huge problem. And yes, it's a myth that a knight needed to be lifted onto his horse with a crane. In fact, modern firefighters are outfitted with suits that are similarly heavy, so you don't need to feel too bad for that knight in shining armor. Unless he was jousting, because jousting armor weighed about twice as much as battle armor and probably was a little on the oppressive side.

Medieval knights had to follow strict codes of chivalry ... most of the time

All that poetry and dancing and lady-impressing was part of a code that medieval knights had to abide by. You've probably heard of it — chivalry is what kept knights on their best behavior and all of the married court ladies in a constant state of swooning. Before chivalry became a thing around the 11th century or so, though, knights kind of had a reputation as being less like Lancelot and more like The Hound, only not quite so polite.

According to History, early knights were given free rein to burn stuff, loot and pillage, and be not-very-nice to the women of whatever town they were plundering. And because of all that, people were quite rightly afraid of them. Eventually, the kings and lords who were in charge of all those knights figured out that they needed to establish some kind of code of polite behavior so all that violence didn't rule pretty much everything that their hired thugs did, from the battlefield to the breakfast table. So the code of chivalry was established to make sure that knights could be members of polite society, when they weren't actually pillaging and plundering. Unfortunately, the expectation of chivalry in the presence of noble ladies did not extend to chivalry in the presence of peasant ladies — the lowborn were still fair game whenever a knight felt like he might want to lay waste to some valley or another.

Early medieval knights got a lot of time off

The good news is, a knight usually didn't have to go to work every single day. In fact, in peace times, early knights only had to serve for 40 days a year. And peacetime service wasn't especially grueling, either. According to Britannica, it might just involve escorting noble people around or standing in front of a castle gate looking intimidating. Like all institutions, though, the institution of knighthood evolved until knights were spending a lot more time in service, and were doing things like mercenary work and bullying tenants.

Wartime service was another story altogether — if the kingdom was at war, a knight might be called up for service pretty much indefinitely, so if you were a knight during, say, the Hundred Years' War, well let's just say you didn't really get much vacation time.

During the later Middle Ages, a knight could simply buy his way out of service by paying "scutage," which was essentially just a tax in lieu of service. So even in those days wealth could keep you out of a war. See, it's a time-honored tradition.

Peacetime didn't necessarily mean medieval knights were safe from mortal peril

It's not like medieval knights spent their leisure time just hanging around the castle binge watching Game of Thrones or anything. During peacetime they still had to meet certain expectations, and one of those expectations was participation in tournaments. Sounds like fun, right? Except in those days there weren't any health and safety committees making sure that tournaments were safe, and no ambulances standing by in case someone got injured. Participating in a tournament was maybe not quite so dangerous as actual war, but it still meant putting your life on the line.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, tournaments usually involved two different events: a mock battle called a "melee" and jousting. The latter, as you probably know, was when two fully armored, lance-bearing knights tried to knock each other off their horses at a full gallop. Knights usually wore heavier armor during jousting, but even so it was a dangerous sport and knights would sometimes die doing it. In 1559, a jousting tournament killed the king of France — Henry II died after his opponent's lance struck him in the face and sent splinters into his eye and brain. Henry VIII received his famous ulcerated leg wound during a tournament, though it didn't kill him until 11 years later. Jousting could also lead to death by trampling, so it wasn't exactly a safe way to spend your time off.

There were some perks to being a medieval knight

Knighthood was grueling and dangerous and not exactly fun, so what was in it for the knights? Well according to How Stuff Works, a knight could be rewarded for his service with a fief, which was essentially just a piece of the king's land that he got to live on for free. As a bonus, his fief was worked by a bunch of peasants who produced food and other stuff that made him wealthy, so having a fief was pretty lucrative — even though technically the king still owned the land you were living on and could take it away if you pissed him off. Fiefdoms were also inherited, so when a knight died the fief was passed on to his eldest son, who also had to be a knight so he could serve the king and maintain his right to hold the fief.

Who you were indebted to also depended on where you lived. In England, a knight was beholden only to the king, but in France, lords who held fiefs could employ knights in their own armies, and it was the lord who gave the knight his armor, horses, weapons, food, and money. The owner of the fiefdom could employ more than one knight, too, so knighthood itself wasn't necessarily a guarantee of wealth and land.

What the king giveth ...

As a knight, you were serving God, but what did that really mean? A knight could go his whole life without ever receiving direct instructions from the lord above, so he had to turn elsewhere for guidance. Sometimes he'd consult a priest but usually he got his orders from the king, who by virtue of royal birth was a direct mouthpiece for God. Being a mouthpiece for God, by the way, was super useful for the king when he wanted to do things like seduce courtiers or chop off people's heads. Anyway, a knight was beholden to his king regardless of whether or not his orders agreed with his conscience. So what happened to knights who disobeyed or in some other way dishonored themselves? Well, a king gave the knight his spurs, so he could also take them away.

According to Noble Dynasty, when a knight who did something treasonous or cowardly (or was just accused of doing something treasonous or cowardly, because there didn't have to be any proof) he got publicly stripped of his knighthood in a formal ceremony. First, he'd have his spurs "hacked from his heels" and his sword broken — if he was lucky, they'd just break it versus actually breaking it over his head. Finally, they'd burn his coat of arms and hang his shield upside down where the whole kingdom could see it. Then they'd execute him, so overall it was not a great day for the knight.

Medieval knights earned a spot in heaven unless they got buried in the wrong piece of dirt

All the infidel-killing and chivalry and holy calling stuff was almost but not quite enough to get you into heaven, which means you could do pretty much everything right as a knight and still spend sleepless nights at the end of your life worrying that you wouldn't make it past the pearly gates. So what's that all about then? Well, even people who were completely without sin could not be guaranteed a place in heaven unless they were buried in a certain kind of dirt. Yes, it's true, not any dirt would do ... it had to be the consecrated dirt of a church graveyard.

In anticipation of solving this problem, a lot of knights — well, those who made it past their youth anyway — would often join a military order, because membership usually came with a plot in a church graveyard. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, an aging knight would sometimes even enlist at the last possible second, so he could be interred beneath a lovely stone effigy in a church forever, without the need to spend a lot of time actually doing churchy things.