What It Was Like Taking Part In D-Day

When it comes to history's greatest battles, there are few that can rival the importance of World War II's Allied invasion of the beaches of Normandy: D-Day. Anyone who knows anything about the war probably knows a bit about this pivotal invasion... but The Atlantic says that something strange has happened with the telling and retelling of the D-Day invasion. They say: "[...] the passing of the years [...] has softened the horror of Omaha Beach [...]"

That's happened, they add, largely because everything about the battle has been documented in a very clinical sort of way, starting with the very first books written by Army historians. We're shown routes and arrows, precise landing spots, the places where German bunkers sat... but that only tells part of the story. What's lost in that kind of telling is the human side: what was it like for the men and boys who headed toward the beach that morning, knowing there was a good chance they were looking at their last sunrise?

Fortunately, some D-Day participants have spoken about what it was like, because remembering? That's important.

D-Day: From rehearsal to the real thing

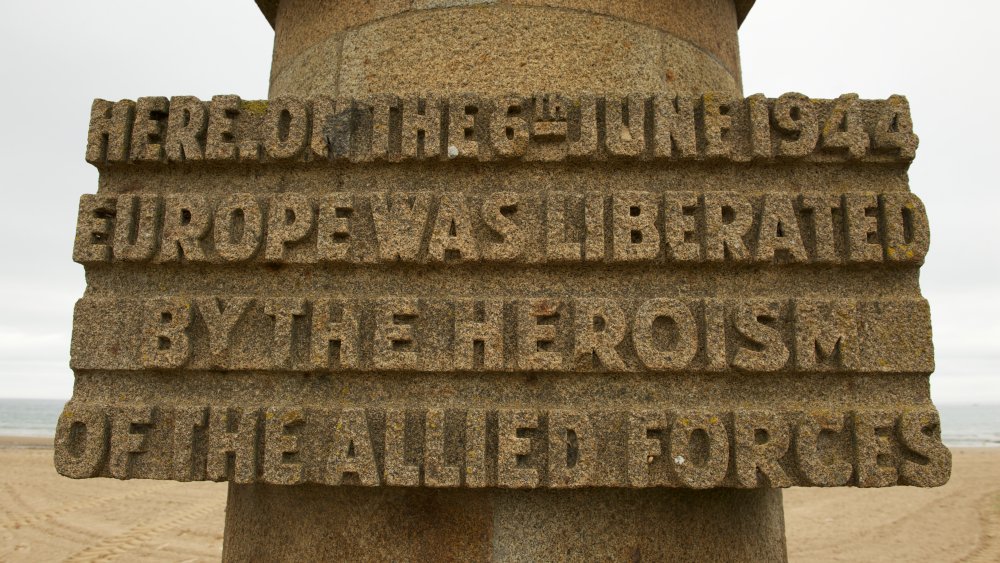

D-Day happened on June 6, 1944. In the months leading up to that fateful day, there was a lot of preparation and planning done, including a practice drill called Exercise Tiger. According to Historic UK, it was April 22, 1944, when those rehearsals were interrupted by the appearance of nine German E-boats. Two of the landing craft were sunk, one was damaged, and men started dying in the cold water. By the end, 749 were dead.

In the middle of the drill was Joseph "Eddie" McCann, who was sent in at the helm of a small boat to rescue survivors. He managed to save 45, and he described a horrible scene (via the BBC). "[...] there were men on fire... men were swallowing their tongues, heads in one place, legs in another place. [...] if [...] I could sense life, we'd brought them out of the water. [...] then I come upon some of my friends. One was Lieutenant JG Saucier. [...] I had to leave him in the water."

McCann went on to take part in D-Day, dropping the men of the 1st Infantry Division onto the beach. He was just 15-years-old. The D-Day Center says he later helped evacuate the wounded, and the carnage haunted him for the rest of his life. McCann died in 2009.

Dead before the beach

The dying started long before they reached the shore. According to The Atlantic, the men of Able Company were being shelled by artillery fire when they were still 5,000 yards out — that's about 2.5 miles. One boat took a direct hit at 1,000 yards, and another made it to within 100 yards before it was hit.

The plan was an orderly march from the boats to the shore, but when the ramp dropped and the men in front were torn apart by machine gun fire, discipline gave way to a struggle for survival and still, many of those who didn't die from enemy fire were drowned under the weight of their own packs.

Ted Cordery was on the upper deck of the HMS Belfast when the invasion launched, and he told the BBC that they had known something big was happening, but they hadn't been given details. The Belfast's role was supporting the troops landing at Juno and Gold beaches — along with being a floating hospital — and from his position operating cranes lifting stretchers on board, he saw a lot: starting with the men who died before they made it to the beach. "I'll die with this memory. [...] and the injuries I saw, I couldn't tell you. There was nothing I could do about it. I looked down at them, and I cried. [...] The injuries — faces, stomachs, legs off — oh, God. [...] Those poor people."

Climbing over the bodies of dead friends on D-Day

It was near evening on that first day, says The Washington Post, that an unknown soldier from the 29th Division's 116th Regiment described the scene in an eerie way: "Thousands of bodies were lying there. You could walk on the bodies, as far as you could see... without touching the ground."

Allied troops soon learned that Omaha was the most heavily defended of the landing points, earning it a nickname: Bloody Omaha. According to The Wall Street Journal, it was another anonymous soldier who remembered, "there were body parts everywhere and the sea turned red with blood." Military historian S.L.A. Marshall says (via The Atlantic) that even as the ramps on the landing craft dropped and men started dying, "Merely to stay alive [was] a full-time job."

D-Day was covered by just a handful of journalists, including, says The New York Times, Ernie Pyle, who reported through the eyes of the sons, brothers, and husbands who were fighting and dying there. He wrote: "Here in a jumbled row for mile on mile are soldiers' packs. Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles, and hand grenades. Here are the latest letters from home... [...] Here are pocketbooks, metal mirrors, extra trousers, and bloody, abandoned shoes."

'I would do it again'

When Russell Pickett returned to Normandy for the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings, he was the last surviving member of Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division. Pickett was 94, reported The Guardian, and most of his fellow soldiers had died on the beach 75 years prior: his company had a 96 percent casualty rate during what was dubbed "the suicide wave."

Pickett was wielding the company's flamethrower, and he was supposed to take out one of the German pillboxes. It didn't happen, though: his landing craft was hit. "It just knocked me coo-coo," he later recounted. Fortunately, another landing craft picked him up. "I saw a lot — too much. A lieutenant on another boat, [...] we thought the world of him, Lt. Fergusson. Well, I saw him running down the beach screaming and hollering: 'I can't see, I can't see.' His whole forehead was down over his face. You couldn't see his face. [...] he ran a few yards, and he was shot down."

Pickett was back in the field six days later, but it was D-Day that haunted him: he'd never gotten to the machine gun nest he was supposed to clear out. "I go over it a lot in my mind. How many could have been saved? But, then, did I want to be the person to use the flamethrower? There were five men in there. [...] But if it came to it, [...] I would do it again."

Overloaded packs and a WWI rifle

Arden Earll (pictured) was 94 when The Washington Post interviewed him in 2019. He was living in a Pennsylvania nursing home, and as he read a list of names of the men who had stormed the beach with him on D-Day, he began to cry. "Sometimes I think, 'Why were they killed and I wasn't?' Why? You don't know."

Earll was 19-years-old when he ran onto the beach in France, so far from his Pennsylvania hometown. He still has shrapnel in his arm, and he calls them souvenirs. And he still remembers what he was carrying, and how he watched his friends die. The year was, of course, 1944. Earll's weapon? A 1903 Springfield rifle. He carried that, six rounds of 81-mm mortar ammunition, and his combat pack. The troops had been promised new rifles, he remembered, but they hadn't come, so they'd made do with weapons dating back to World War I.

He remembered, too, the pride that his squad leader — 21-year-old Noel Washburn — had taken in caring for the weapons his life depended on. He made it a point to never have a dirty rifle, and as they left the landing craft that morning, he made it 20 yards before he dropped, right in front of Earll. "Something had hit him all up and down the front of him," Earll remembered. "He went back down into the water and never got up."

The noise of D-Day

The sights and sounds of D-Day have haunted those who survived for decades, and for those who weren't there, it's impossible to fathom the sounds of battle.

Then, in 2019, a researcher in Florida came across something incredible (via The Washington Post): a 13-minute long audio recording on a terribly obsolete format. It was the voice of a journalist named George Hicks, who was standing on the deck of a ship off the coast at Normandy. The tapes are chilling: gunfire and screams, shouting, cheering, and a blow-by-blow account of what he saw. "Something is burning and falling down through the sky! Circling down... maybe a hit plane. [...] They got one! They got one... A great blotch of fire came down and is smoldering now, just off our port side in the sea. Smoke and flame there."

Hicks was still a bit removed from the action, though, so what about the ground troops on the beach? Combat medic Ray Lambert describes the sounds of D-Day like this (via the Smithsonian): "The noise of war does more than deafen you. It's worse than shock, more physical than something thumping against your chest. It pounds your bones, rumbling through your organs, counter-beating your heart. Your skull vibrates. You feel the noise as if it's inside you, a demonic parasite pushing at every inch of skin to get out."

The Beast of Omaha

Private Heinrich Severloh described the early hours of D-Day as being pretty much like any other day (via HistoryNet). He took up his station in a Widerstandsnest — "resistance nest" — at around 1 am, and around 5 am, he recalled: "...the horizon parted to reveal an endless, uninterrupted band of ships, some of them huge. The sight was eerie. Things were about to get ugly."

Severloh could see almost the entire beach from his position — inside a bunker, with 13,500 machine-gun rounds and 400 rifle rounds. He recounted the morning to All About History: at first, there was complete silence. They watched as troops jumped in the water, as some drowned, and as others slogged toward the beach. "We were well aware that the GIs below us were being led like lambs to the slaughter." For the next nine hours, Severloh fired, alternating between the machine gun and rifle. By the time he ran out of ammo and fled, he had earned himself the nickname "the Beast of Omaha," responsible for thousands of Allied casualties.

And it haunted him. He later said (via The Scotsman): "I never wanted to be in the war. I never wanted to be in France. I never wanted to be in that bunker firing a machine gun. [...] I do not know how many men I shot. It was awful. Thinking about it makes me want to throw up."

The medics at Ray's Rock

In 2019, the Smithsonian called Ray Lambert "the last man standing." Then 98-years-old, he was one of the only surviving members of the first wave of men who stormed Omaha Beach.

Lambert was a 23-year-old medic in 1944, and was shot almost the instant the ramp of his landing craft dropped. His elbow shattered, he took shelter behind a massive rock (pictured) and started dragging wounded soldiers behind the rock. That, says NPR, is when he was shot again. This time, it was his leg that was opened to the bone. Lambert got a tourniquet on, shot himself full of morphine, and turned to another medic to ask him to take over. That medic took a bullet to the head... so Lambert kept going. He lost track of how many lives he saved. Lambert's stint on the beach only ended as he was trying to drag a soldier out of the water, and was caught beneath an opening landing craft ramp. His back broken in two places, he was eventually plucked from the water... after saving the soldier.

The rock is still there, and now bears a plaque with Lambert's name, and the names of his fellow medics. He returned often to remember them, and said he knew 2019 would be his last trip. He said: "The way I'd like to be remembered was a guy that was willing to die for my family and for my country, and a good soldier and a good person."

The 320th Balloon Battalion

It was 2009 when The New York Times tracked down the last surviving member of the 320th Balloon Battalion. William G. Dabney was 17-years-old when he enlisted, and he volunteered for a "special service." It wasn't loading ammunition as he expected but flying massive silver balloons that were designed to interfere with airborne forces' ability to target and strafe ships and ground troops.

It was no simple feat: extensive training was required to learn how to handle the 35- to 60-foot-long balloons in all kinds of weather, and to fill them with more than 3,000 cubic feet of highly flammable hydrogen gas. According to the Smithsonian, there were a handful of barrage balloon units trained during the war, but it was the 320th that went ashore on D-Day.

Balloons were lofted, then replaced as soon as they were shot down — by the dozens. Raised at night for protection and lowered during the day to make way for Allied bombers, it was long, hard, terrifying work in the middle of front line chaos. Sergeant George A. Davidson, who died in 2002, wrote in a letter home that they were "ducking bullets and anything that would kill a man," and they were "too afraid to be afraid." The unit had a medic, too, named Waverly B. Woodson, Jr. He, says Time, was wounded getting off his landing craft, but spent the next 30 hours treating wounded soldiers on the beach.

The codebreakers at Bletchley Park on D-Day

Those taking part in D-Day weren't all on the front lines — the codebreakers of Bletchley Park were front and center, too.

According to the BBC, codebreakers spent the duration of the landing intercepting communications, translating them, and passing them on to Allied commanders. The information was invaluable and contained German chatter about not only the movements of the Axis, but how much they knew about the Allied efforts and locations. For most of the war, the codebreakers received their information through Y stations — silent, off-site listening posts. But time was crucial on D-Day, and it became the only time during the war that Bletchley Park had its own listening station. An average of two and a half hours passed between communication interception and an information relay to the front lines.

Still, The Guardian says that there was still a sense of guilt hanging heavy over the staff. They weren't on the front lines, they weren't in the line of fire, and it was Eric Jones, the head of Hut 3, who sent a memo to everyone, reassuring them that they were, in fact, saving lives. "It's a thought we cannot avoid and it's a thought that inevitably aggravates an ever-present urge to be doing something more active; to be nearer the battle, sharing at least some of the discomfort and dangers. [...] There is no back-stage organisation..."

What happened to the first German soldier to see the D-Day invasion?

His name was Helmut Romer, and the 18-year-old was guarding the Pegasus Bridge (pictured) over the Caen canal when the first glider full of British troops landed 50 yards from him. He fired a single flare before the British troops started firing on them, and Romer "decided to leg it, and we threw ourselves into an elderberry bush."

Romer watched as the invading forces killed his fellow soldiers, then moved through. Pegasus Bridge, says the BBC, was captured in just 10 minutes with two Allied casualties — who were the first of D-Day's many dead. Romer watched from the bushes, and 36 hours later, he and two of his fellow soldiers decided to give themselves up. "We were exhausted and we decided to hand ourselves over to the British, thinking, 'Either they will shoot us or they'll take us prisoner.'" They were taken prisoner, and he told The Telegraph, "Thank goodness for us they didn't kill us. [...] I think we must have looked so pathetic, they quickly realized we were not much of a threat."

Romer ended up spending two years in a POW camp in Canada, and in 1962, he saw himself portrayed in The Longest Day, as a skinny soldier who ran away. "It did affect me," he said. "When I met my future wife, Luise, at a dance class in the late 40s, I warned her, 'Do you really want to marry me? After all, I'm a coward.'"

The French civilians on D-Day

Soldiers weren't the only ones at the beaches in Normandy on D-Day: there were civilians there, too, and those who survived would never forget the things they saw. And many did not survive — the Independent estimates that somewhere around 20,000 civilians at Normandy were killed throughout the conflict.

Then, there were people like Marguerite and Remy Cassigneul. Then teenagers, they had spent four years of their lives living under Nazi rule when the Allied invasion landed at Juno Beach, just a stone's throw from their hometown of Tailleville. Gunfire and explosions had woken Marguerite from sleep, she told DW, and it was 3 am when she and her family went into hiding — first in a trench, then, in a stable. Canadian troops found them the next day, and Marguerite remembered serving them Calvados.

They weren't there long, as the soldiers instructed them to leave their homes in case the Germans came back. So, she went to the beach with her cousin: "That will stay with us. Even today, I don't understand how people can enjoy themselves on the beaches."