The Long And Tragic History Of Artsakh

The conflict in the region of Artsakh, also known as Nagorno-Karabakh, is quite recent compared to the history of Artsakh itself. Artsakh, now situated in Azerbaijan, was known during the Uratrian period as "Urtekhe" and by the fourth century BC, it bore the name "Artsakh". The name "Karabakh" comes from the fourteenth century as a Persian-Turkish fusion of the Persian word "bagh," meaning "garden," and the Turkish word "kara," meaning "black." And the name Nagorno-Karabakh comes from Russian rule, with "Nagorno" coming from the Russian word "nagorny," meaning highlands.

On February 20th, 2017, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh voted to change its name to the "Republic of Artsakh." But people still use the variety of names to refer to this ancient region because no one name can encapsulate the countless identities this region has had over thousands of years.

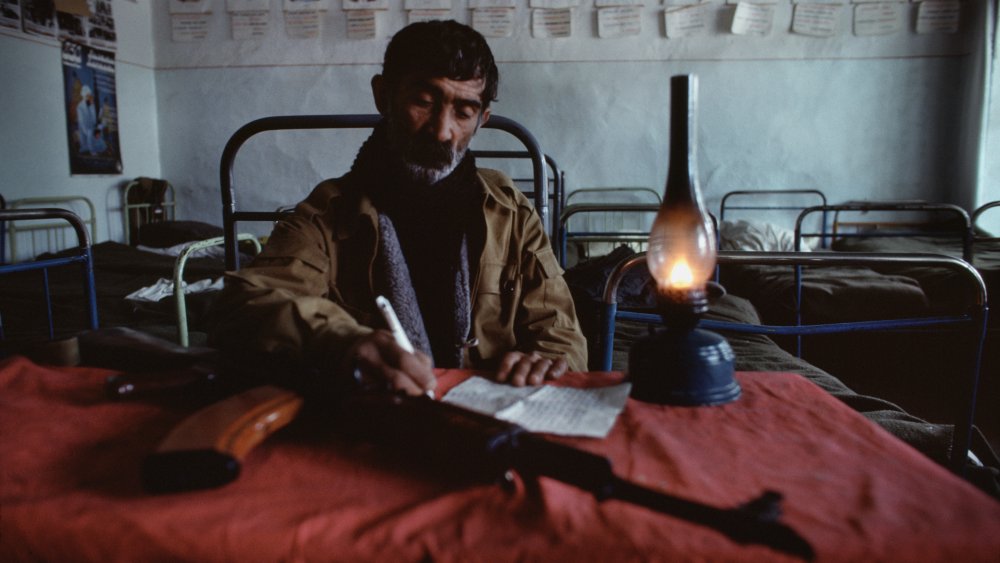

Artsakh has repeatedly declared its independence, and the people of Artsakh have been denied time and time again their right to self-determination. And on September 27, 2020, war broke out once more in the region as Azerbaijani forces started bombing Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh. Backed by Turkey, Azerbaijan is instigating a confrontation in an effort to distract people from its deepening political crisis and mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic. But despite everything, the people of Artsakh continue to fight for their existence. This is the long and tragic history of Artsakh.

Artsakh of antiquity

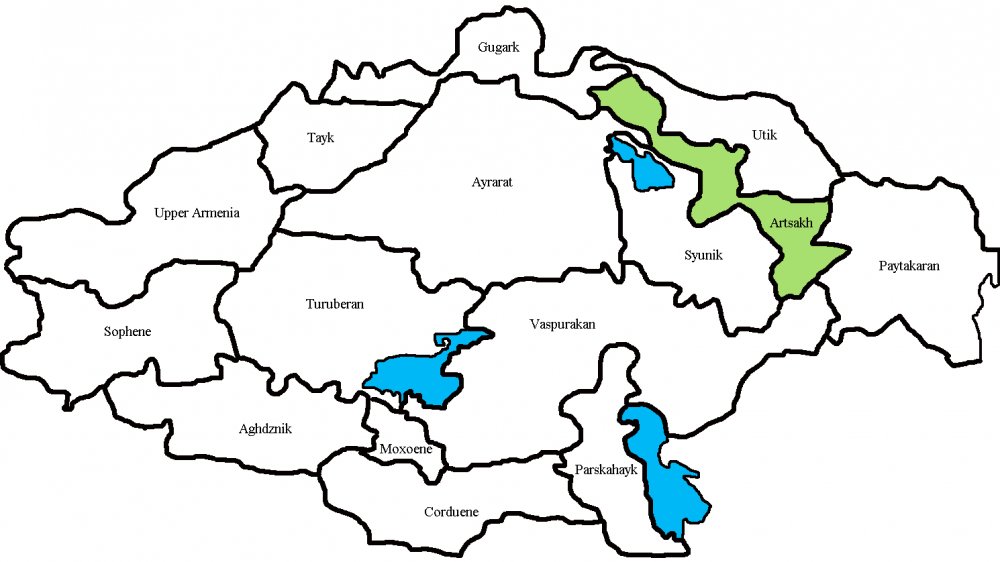

After the Kingdom of Urartu collapsed in the sixth century BC, the Yervanduni dynasty took power and established the Kingdom of Armenia, incorporating the territory now known as Nagorno-Karabakh as the province of Artsakh. But even during the Urartu period, Artsakh is mentioned in various inscriptions.

According to Ancient History Encyclopedia, the Yervanduni dynasty ruled until the second century BC, initially under Persian and then under Seleucid control. But after a coup, likely instigated by the Syrian King Antiochus III, resulting in the murder of Armenian King Orontes IV, King Artaxias came to power, ushering in the Artaxiad dynasty.

Under Tigranes II, who ruled from 95–56 BC, the Kingdom of Armenia became the strongest state to the east of Rome and freed itself from Seleucid rule. During his reign, Tigranes II also established several cities in his name. Tigranakert in Artsakh features ruins and artifacts from pagan and Hellenic eras and was also a hub for early Christianity. But some of Tigranakert's earliest monuments come from the pre-Christian era, including large anthropomorphic stone idols and Sahmanakars, or border stones.

The Greek geographer Strabo, who is estimated to have lived from 64 BC to 23 AD, included Artsakh in his geographic description of Greater Armenia, writing that the entire population spoke Armenian by the second or first century BC, an observation confirmed by archaeological finds.

Fall of the Kingdom of Armenia

When the Kingdom of Armenia was divided between Persia and Roman Byzantium in 387 AD, the provinces of Artsakh and Utik, the tenth and twelfth provinces of the Kingdom of Armenia, were part of the Eastern Armenian Kingdom and fell under Persian rule.

According to Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Conflict in the South Caucasus, the Armenian kingdom was terminated by the Sasanid Persians in 428 AD and the provinces of Artsakh and Utik were reorganized into the marzpanate, or border province, of Aran, also known as the province of Albania, along with the former Kingdom of Caucasian Albania as well as tribes living by the Caspian shore.

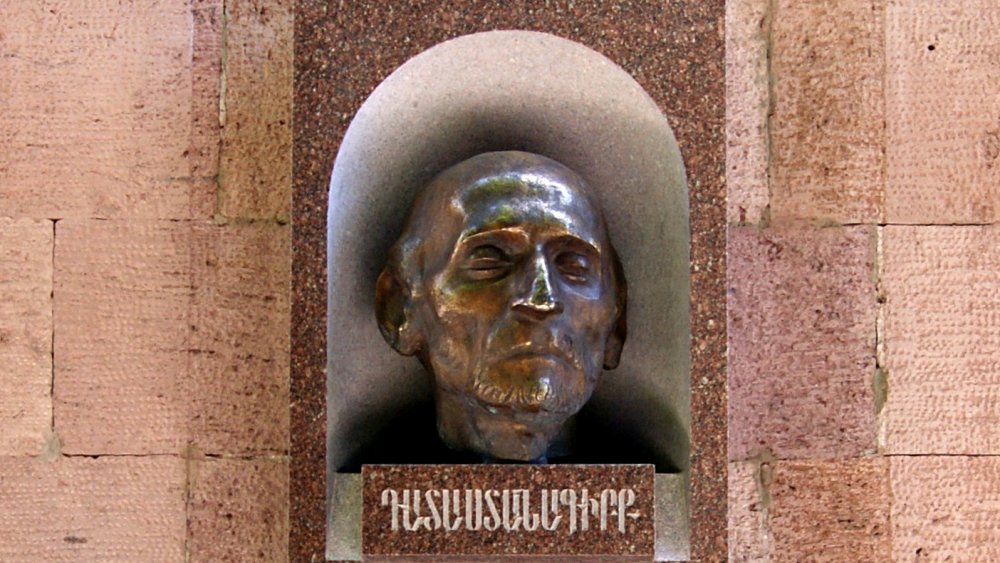

According to "Azerbaijan's Prospects in Nagorno-Karabakh" by Alec Rasizade, Aran/Artsakh remained under Persian rule until the 7th century, when Persian rule was replaced by Arab rule. But the Armenian homogeneity of the region led to the proliferation of the Armenian language and culture, especially after Mesrop Mashtots's creation of the written Armenian alphabet in the 5th century.

The spread of Christianity in Artsakh

The province of Aghvank, including Artsakh and Caucasian Albania, converted to Christianity early in the 4th century and the Albanian Church was considered a branch of the Armenian Church. St. Gregory the Illuminator is credited with Aghvank's conversion to Christianity and his grandson, Grigoris, was made head of the Aghvank Church around 330 AD.

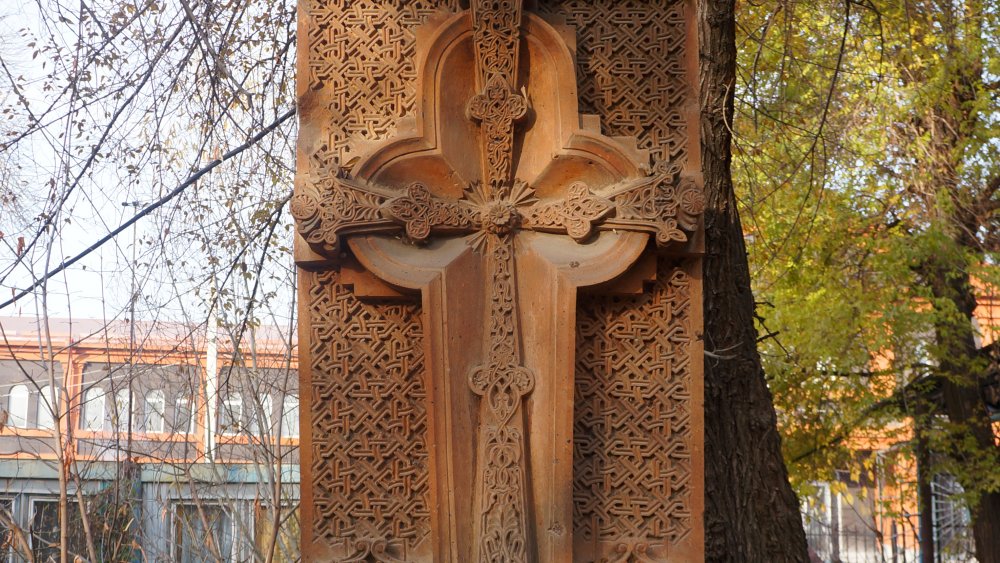

According to The Caucasian Knot, the mausoleum dedicated to Grigoris "stands as the oldest dated monument" in the region. Located in the monastery of Amaras, Amaras is also said to have housed the first religious Armenian school in Artsakh, opened by Mesrop Mashtots. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, over 40 major religious centers and monasteries were built in Artsakh.

Although the influence of Christianity began to wane after the invasion of the Arab Caliphate and the Islamization of parts of Aghvank, Artsakh remained somewhat Christian. While some principalities converted to Isalm, Artsakh "rapidly Armenized," in comparison. By the 9th century, Artsakh was reintegrated into the Armenian Kingdom of Bagratids as the Principality of Khachen.

By the 13th century, there were over 5,000 churches in Artsakh, many of which are now in ruins or have now been destroyed.

Medieval Artsakh

During the Middle Ages, Artsakh was repeatedly conquered. First by Arabs in the 8th century, then by Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, and then by Mongols in the 13th century. However, according to Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Conflict in the South Caucasus, Artsakh was somewhat able to maintain its local autonomy under their local feudal leaders.

From the late 12th through the 13th century, Artsakh's architecture flourished, with monasteries of this time serving as centers of scholarship and art as well as centers of refuge. According to The Uses of Justice in Global Perspective, 1600–1900, it was also in Artsakh that Mkhitar Gosh composed the legal treatise Datastanagirk, or Codex of Armenian Law, in 1184. The law code was used in Greater Armenia and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and in 1519, King Sigismund of Poland also adopted it as law for the Armenian colonies in Lvov.

The Meliks and the battle against foreign domination

"Melik" is a term for the Armenian nobility that existed during the feudal period of the Principality of Khachen. During the various invasions, these noble families were a powerful force for Armenian independence and allowed for the preservation of Artsakh's autonomy.

Meliks ruled principalities called Melikdoms, and according to Brief History of Artsakh, in 1735, five Melikdoms joined forces to form one political-administrative entity known as the Khamsa Melikdoms. For a brief period in the second half of the 1700s, the Meliks were subordinate to the Karabakh Khanate, a Turkish principality.

Lasting until the 19th century, the Khamsa Melikdoms were a strong political force, cooperating with the Mongols and resisting the invasions of the Ottoman Empire from the 16th to the 18th century. But when they couldn't do it alone, they reached out and corresponded with monarchs around Europe.

According to Mountainous Karabakh, after Peter the Great of Russia began his Caucasian campaign in 1721, he encouraged Armenians to secure Artsakh and its surrounding region. But after doing so, he then urged Armenians to abandon Artsakh and move instead to northern Persia or Baku instead. However, they resisted and continued battling against the Ottoman Turks. In 1736, under Persian rule, Nader Shah recognized the autonomy of the Armenian Meliks once more.

Russian influence in Artsakh

After the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, Artsakh was transferred from Persian to Russian rule. The Meliks put themselves in the service of the Russian Tsar, in the hopes that he would assist with Artsakh's reunification with Armenia, but they were ultimately sorely mistaken.

According to The Caucasian Knot, in 1827, the Meliks submitted a plan for the reunification of Armenian lands, including Artsakh and the Karabakh region. But the plan was rejected by Tsar Nicholas I. Artsakh remained in what was eventually named the Elizavetpol province while a separate "Armenian Province" was created in the 1820s, including only the principalities of Yerevan and Nakhichevan.

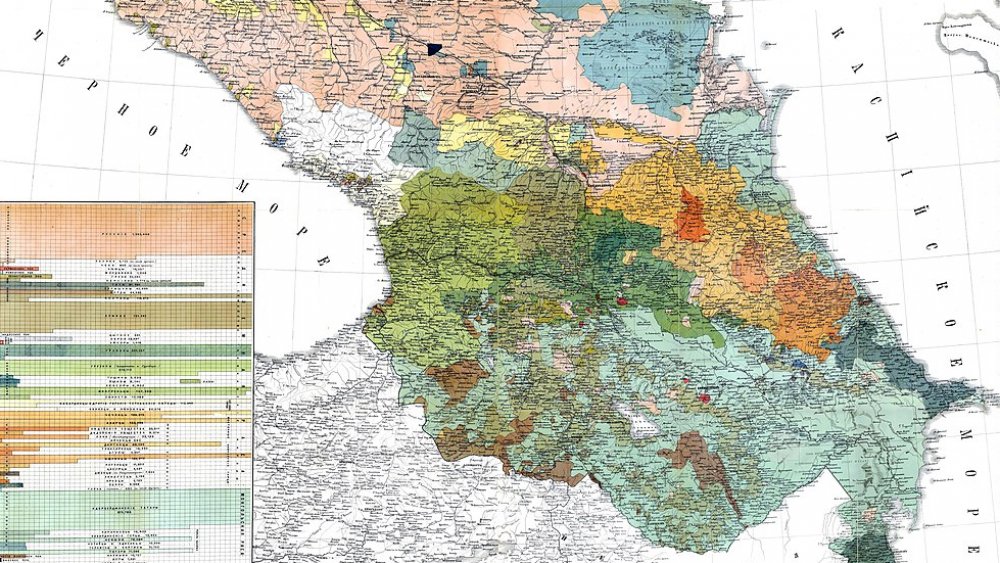

Per the Brief History of Artsakh, during this time, the town of Shushi flourished and Armenian districts were rebuilt after having fallen into disrepair during Persian rule. Multiple printing houses and educational centers were established, and soon Shushi became a key center of Armenian culture and arts. The population included both Tatars, known today as Azeris, and Armenians. The population was split fairly evenly, with 11,595 Tatars and 15,188 Armenians counted in 1826.

Armenians were especially concentrated in the mountainous part of Artsakh, the region currently known as Nagorno-Karabakh. According to Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, fleeing hostilities in Persia, thousands of Armenian refugees migrated to the Armenian and Artsakh provinces after 1828.

The March and September days

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Artsakh joined the Transcaucasian Federation, which broke up the following year into the republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Unfortunately, 1918 was also a year of bloody ethnic cleansings in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.

According to "Creating the 'Enemy Nation,'" the first bloody encounter lasted from March 30 to April 2, when between 10,000 and 30,000 Azerbaijanis were murdered. Beginning as a conflict between the Azeri Musavat Party and the Bolsheviks, the Armenian Dashnaktsutyuns eventually joined on the side of the Bolsheviks after refusing an alliance with the Azeris. The following September, between 10,000 and 30,000 Armenians were killed in retaliation for the massacres earlier in the year. As a result, the massacres are dubbed the March Days and the September Days.

Between these two massacres, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia all declared their independence in late May 1918. Azerbaijan tried to claim the region of Artsakh for itself, but the people of Artsakh held their own congress and declared independence as the Karabakh People's Government in July 1918.

After this first Congress, the Government of Azerbaijan enlisted the assistance of the Turkish armed forces. After the ultimatum issued by Noury Pasha, commander of the Turkish armed forces, was rejected by the Second Congress of Karabakh Armenians, the Turkish forces entered Baku and left thousands of Armenians dead in their wake on September 15, 1918.

1920 destruction of Shushi

In just the month of March 1920, roughly 20,000 Armenians were deported from Shushi while another 20,000 were murdered. Azeri and Turkish forces pillaged the city and set fire to what was left, burning Shushi to the ground.

This wasn't the first time that Shushi had been targeted. According to Terrible Fate by Benjamin Lieberman, in June 1919, roughly 600 Armenians were massacred in Shushi and its neighboring villages. After Armenian militias rebelled in Shusha, Terter, and Askeran on March 22 and 23, 1920, the Azeri government led their forces into Shushi in retaliation.

As noted by Portraits of Hope, Nadezhda Mandelstam wrote in her memoirs that when she and her husband Osip Mandelstam, the Russian poet, were in Shushi, he couldn't bring himself to eat "because he felt Armenian blood in the bread." Some of the damage from the assault on the city was still visible in the 1960s.

Stalin gives Artsakh to Azerbaijan

In 1920, the Soviet army first annexed Azerbaijan and then Armenia. Initially, the Bolsheviks had promised to reunite Artsakh with Armenia, as well as the regions of Nakhichevan and Zangezour. And for a moment, it seemed as though they were actually going to follow through. According to "Undeclared War" by Svante E. Cornell, under pressure from the Soviet government, the revolutionary committee of Soviet Azerbaijan issued a statement in December 1920, that Nakhichevan, Zangezur, and Artsakh were to be reunited with Armenia. But then in 1921, in an effort to placate Turkey, Stalin determined that the Artsakh and Nakhichevan were to remain under Azerbaijan's authority.

In 1923, Stalin formally transferred Artsakh to Azerbaijan, establishing it as the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, a province with its own Soviet administration and legislative body that was subject to the Azerbaijani SSR. Stalin also redrew the map, effectively splitting Artsakh and introducing a strip of land in between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. This strip of land was given to Azerbaijan, as was Nakhichevan, even though it lacked a border with Azerbaijan and has historically been an Armenian province.

Mass appeals for reunification in Artsakh

Between 1920 and 1977, the people of Artsakh repeatedly appealed to Moscow for reunification with Armenia. Thousands of residents from Nagorno-Karabakh signed mass public appeals requesting reunification with Soviet Armenia, periodically also petitioning the Kremlin for protection from Baku's abusive policies. According to the EVN Report, the majority of these letters and appeals came after World War II. Grigory Arutyunov, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Armenian SSR, even wrote to Joseph Stalin himself in November 1945, asking for a reunification, hopeful that Stalin would agree given the recent territorial acquisitions of Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan refused.

Through deliberate discrimination, Azerbaijan simultaneously tried to force Armenians out of Nagorno-Karabakh. The leader of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, admitted during an interview that he did everything in his power to change the demographics of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The government also refused to invest any public funds towards developing the infrastructure in Nagorno-Karabakh. Radio and TV transmissions from Yerevan, Armenia's capital, were banned while Armenian schools and churches were also closed.

Pogroms and massacres in Artsakh

In 1988, Artsakh's independence and reunification movement were revived during Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika policy. There were demonstrations in Stepanakert and Baku demanding Artsakh's reunification with Armenia. And on February 20, 1988, the Karabakh Council of People's Representatives adopted a resolution again asking for reunification. The Karabakh Committee was also created to work towards the goal of reunification.

Although Armenia didn't formally respond, the Azeri government did with a series of bloody pogroms against Armenians in Sumgait and Kirovabad. Some reports say that Alexander Katusev, the military prosecutor of the USSR, "put a match in a tinderbox" when he said that two Azeri men had been killed in Artsakh. However, it was established that at least one of the men who was killed was shot by Azeri police.

The massacre claimed upwards of 360 Armenian and six Azerbaijani lives. The death toll in Kirovabad was over 100 and in 1990, a seven-day pogrom in Baku killed hundreds and displaced thousands. Those who carried out the pogroms even had lists of Armenian names and addresses. By December 1989, the Soviet authorities had also arrested the Karabakh committee members, although they were eventually released the following May.

Between 1988 and 1990, at least 300,000 Armenians fled or were deported from Artsakh and Azerbaijan, and over 150,000 Azeris fled Armenia since the Armenian authorities were unwilling to protect them from discrimination and violence. During all of these pogroms, the Soviet army, which was present, did nothing.

Post-soviet Artsakh

As the Soviet Union crumbled, Artsakh once more declared its intention for independence as the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh on September 2, 1991, three days after Azerbaijan declared its own independence. While the declaration of independence was both a political move that would allow Artsakh to negotiate on its own terms rather than relying on Armenia's negotiations, it was also an act of self-declaration since Artsakh had never entirely aligned with Armenia's agenda.

Less than one month after Artsakh declared its independence, Stepanakert was shelled for the first time and as attacks became more common, this period became considered Azerbaijan's declaration of war. Undeterred, the people of Artsakh voted overwhelmingly (99%) for independence in the referendum of December 10, 1991, although notably, no Azeris took part.

Unfortunately, according to Black Garden by Thomas de Waal, in less than a year Artsakh's "de facto leader of the region" and speaker of Artsakh's newly elected parliament, Artur Mkrtchian, was also found dead in mysterious circumstances. After his death in April 1992, relations with Armenia reportedly improved.

War, massacre, and a farcical ceasefire

Azerbaijan tried to suppress Artsakh's Armenian population in early 1991 through "Operation Ring," which sought to deport the Armenian populations in 24 villages. From late 1991 to mid-1992, Azeri forces also bombed various cities in Artsakh.

According to EAFJD, by the summer of 1992, half of the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh was occupied by Azeri forces and displaced the Armenian population. By 1993, Armenian forces were able to overtake several cities and make land gains while Azerbaijan's offensive had displaced upwards of 40,000 Armenians.

The town of Khojaly suffered a massacre in February 1992, during which Armenian sources claim Azeri armed forces used people as human shields, while the Azeri government insists that this was a genocide perpetrated by Armenians. While the course of events remains contested, according to Europe's Next Avoidable War, "several non-Armenian sources report the existence of pre-attack warnings, the escape of more than 2,000 civilians through a humanitarian corridor, as well as the discovery of most Khojaly casualties in an Azerbaijani-controlled sector." The death toll estimates range from 180 to 600.

On May 12, 1994, Russia brokered a ceasefire that has been violated repeatedly over the years. At the time of the ceasefire, Armenia occupied 9% of Azerbaijani territory, not including Nagorno-Karabakh.

Once more faced with the horrors of war in Artsakh

The ceasefire has been broken repeatedly and little was done to reconcile Artsakh, Armenia, or Azerbaijan. And per Europe's Next Avoidable War, edited by Michael Kambeck and Sargis Ghazaryan, it's never been possible to determine who violated the ceasefire first. By 2007, over 400,000 Armenians and 600,000 Azeris had been displaced by the war.

In recent years, both the president of Azerbaijan and the mayor of Baku have made incendiary remarks regarding the extermination of Armenians and have encouraged the destruction of Armenian khachkars in an act of cultural genocide.

In 2016, Azerbaijan launched a military attack in northern Artsakh and over four days at least 200 people were killed and hundreds more were wounded. In September 2020, fighting broke out with a bombing in Stepanakert once more and the conflict again escalated into war. As both sides become inflamed and accuse one another of breaking the ceasefire, lives are being lost and history is being destroyed.