The Untold Truth Of Foot Binding

Body modification has an incredibly long history — as soon as we were aware of the way we look, we were trying to change that for one reason or another. One of the most drastic forms is foot binding, a Chinese practice that Ancient History says started during China's Tang Dynasty (which began in 618).

Perhaps. It turns out that it's a little more complicated than that. NPR dates the origins of foot binding to 961, while other stories put it somewhere around 1700 BC. That's a lot of wiggle room and just goes to show how fuzzy history can get sometimes.

We do know that it wasn't until 1874 that a British priest started the first anti-foot binding society, and while it wasn't outlawed for almost another 35 years, the practice continued long beyond that. The numbers are almost unthinkable: In the 19th century, nearly 100 percent of upper-class women had bound their feet, and half of women overall had gone through the agonizing, crippling procedure. Estimates suggest that as many as two billion women have had it done ... so what is it, how did it start, and why on earth would they go through something so painful and permanently life-changing?

Foot binding started with dance

There are a few different versions of just how foot binding started, and NPR says one of the oldest dates back to the Shang dynasty. That story suggests that it was a Shang empress who had a clubfoot and ordered everyone to bind their feet in solidarity that started the practice, but that's not the only tale.

Fordham University says that while historical evidence is lacking, there's textual evidence that small feet were prized as a standard of beauty as far back as the Han Dynasty — between 202 and 220. By the time of the Tang Dynasty, the upper classes were lauding the beauty of court dancers, who were known for their little feet and the tiny shoes they could wear. Small feet became a mark of beauty and elegance in the upper classes, and lower classes began to mimic that.

According to the Smithsonian, Yao Niang was a dancer in a tenth-century court who wrapped her feet and shaped them into the form of "a new moon." It allowed her to dance on her toes inside of a golden lotus, and the Emperor fell in love with her. In another version, it was the emperor who ordered her — his favorite concubine — to bind her feet and dance. Her famous golden lotus went on to give its name to the most desirable of feet: the very tiniest of them all.

Foot binding was widely practiced and widely condemned

According to the Huffington Post, the practice was widespread by the 12th century. The idea was that girls born in a lower class would have the opportunity to marry up if they had tiny feet, and some weren't afraid to say just why little feet were so desirable.

Zhu Xi was (via the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) one of the most important philosophers of the Southern Song, and in terms of influence, he was second only to Confucius himself. That makes him a pretty big deal, so when he started writing that foot binding would prevent women from going on and partaking in all kinds of "unchaste" and "immoral" behavior, people listened. This proverb became a way of life (via the Hong Kong Medical Journal): "If you love your daughter, bind her feet; if you love your son, let him study."

Not everyone was a fan of that train of thought, though. Even as the practice started spreading through the countryside, teachers of Ruism spoke out against it. Some (like Che Ruoshui) wondered why anyone would want to "torture" their daughter "with so much pain," while others said it was a vanity that made a woman incapable of working to her full potential.

They also taught that it was a matter of respect: Everything we are, we got from our parents. Respecting them meant not harming this gift that they gave us, and that meant not breaking, binding, and reshaping feet.

There were different styles of foot binding

Foot binding, says Fordham University, was not a standardized practice. There was no one way to do it, or a single, idealized way to re-form the shape of the foot.

Researchers say (via LiveScience) that at first, many women were trying to create a narrower foot by wrapping it, and these early attempts didn't do too much to distort or damage the actual bone structure of the foot. By the 1600s, there was a difference in the preferred style in the north and the south of China.

The Wall Street Journal says that with the "cucumber" foot, the four toes were folded under and broken, while the big toes were left straight — which was popular in the south. Others would have their foot bent and compressed lengthwise as well, and that served to make the foot even less stable. It also meant that many upper-class women were so crippled by it that they were assigned a companion when the process was started who would help her care for her feet and carry her when she was unable to walk.

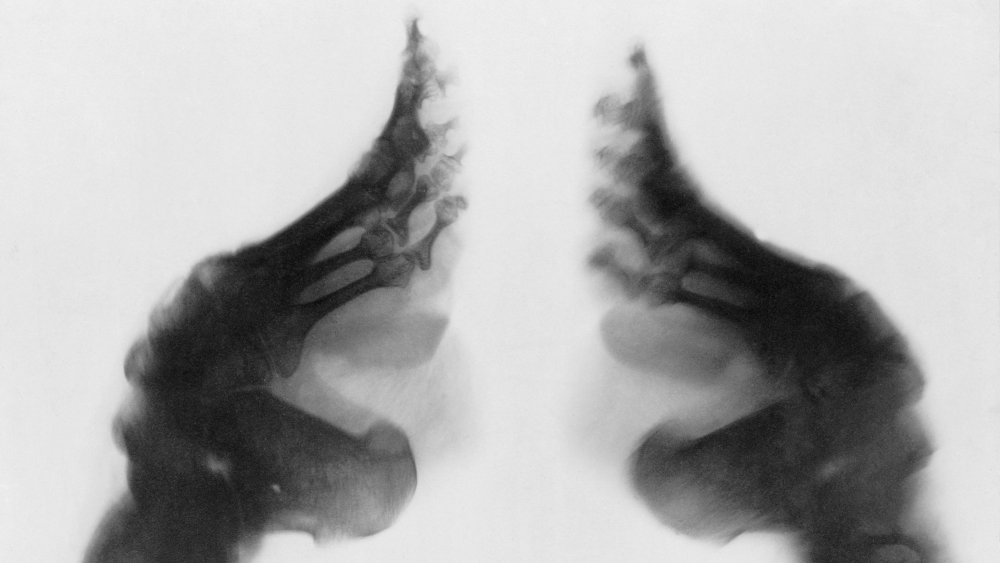

Skeletal remains of women with bound feet have shown that at their most extreme, the process "dramatically altered" the bones of the foot. Few toe bones have actually survived.

Marriage prospects and the lotus feet

The tiny shoes worn by some women with bound feet are called lotus shoes. They're so named, says The Wall Street Journal, because in the most extreme form of foot binding, the final shape of the foot was said to resemble a lotus bulb.

And this is where it gets a little strange. It's sort of understandable as a status symbol, for women who have the luxury of having others do all their work for them. But John Vollmer, an expert on Asian fashion and museum curator, says "Almost every class of woman had some kind of foot-binding." And it makes less sense if you're, say, working in the fields or chasing animals around all day.

It's still disputed as to just why it became so widespread, and one part is that it was believed to increase a woman's marriage prospects and the likelihood of a sort of Cinderella story. Once the process was done, the ideal was the golden lotus: a foot just three inches long that showed in a very physical way that a girl had desirable characteristics, like "obedience and restraint." The Smithsonian says that a silver lotus — a foot that was just four inches long — was still respected, but anything longer than five inches was deemed an iron lotus, and then? Well, a good marriage was pretty much out of the question, and girls who protested — or tried to unbind their feet — would be reminded of that.

How was foot binding done?

The pain of the foot binding process is unfathomable, and if it was going to be done, it would be started when a girl was just five or six years old. According to the Smithsonian, it started mildly enough: with a soak in hot water, a pedicure, and a massage. Then, all the girl's toes would be broken, folded under her foot, and bound so they lay flat against her sole. Then, the arch of her foot was bent as far as possible and also bound tightly with long strips of cloth.

After all that, they were forced to walk. The idea was to speed up the process of breaking the arch of the foot so it could be bent even farther. Bindings were regularly tightened, and the foot would eventually heal into a form that — ideally — crushed the toes and the heel together and formed a deep cleft along the sole. The entire process could take from two years or well into a girl's teenage years, says Ancient History, and while there were professional foot binders who would do the process for some, for others, it was just done by a mother, grandmother, or other older family member.

In addition to the breaking of the bones and the reshaping that was done with the bindings, those bindings had another purpose: They were wrapped so tightly that they restricted the amount a foot would grow.

Horrible things could happen while the process of foot binding was being done

Once the foot binding process was started, The Atlantic says that women would keep the bindings on their feet for the rest of their lives — and if it seems like the trauma of having toes broken and bent over and over again then walking on them is a recipe for all kinds of problems, it absolutely was.

While it was being done, the bandages would come off every two days so the foot could be cleaned, and any buildup of pus or blood could be removed (via the Smithsonian). Infection — and sometimes, the onset of gangrene — wasn't uncommon, and that's not entirely surprising, considering that sometimes, skin deemed "excess" was cut off, and further rot was actually encouraged.

Ancient History says that bandages also needed to be removed to treat regularly-occurring skin ulcers. All the bending and breaking of the foot interfered with a girl's circulation, and skin ulcers, Healthline says, are open sores that develop because of poor circulation. As if that all isn't bad enough, it also wasn't uncommon for girls to lose a few toes in the process, which The Guardian calls "auto amputation."

Some girls dealt with punishment in addition to the bindings. Su Xi Rong was 75 years old in 2008 and told photographer Jo Farrell (via The Guardian) that she had tried to unbind her feet. When she was caught, her grandmother cut some of the skin off her toes.

Foot binding wasn't always forced on girls

It's easy to see the women who went through foot binding in an excruciating process as victims of social and cultural norms, as beholden to beauty. But when British photographer Jo Farrell started interviewing some of the last women to have it done, she found that wasn't always the case.

She said (via The Telegraph): "They were proud of what they achieved. Most will show the size of their feet and explain that they used to be smaller. They were the most beautiful in their village because of their small feet."

She also found that it wasn't always forced on young girls — in fact, the opposite was true. "Some women bound their own feet as their mothers and grandmothers would refuse, and they wanted to fit in with those in their village. They had watched their mothers binding their own and copied."

Guo Ting Yu — who was 83 in 2010 — was one of those women (via The Guardian). Her mother refused to bind her feet, so when she was 15 years old, she did it herself. Decades later, all her toes remained folded under her feet, but she hasn't reduced the length of her foot — the ultimate goal.

There were economic reasons for foot binding

The motivations behind foot binding haven't always been 100 percent clear, says The Wall Street Journal. While it's long been accepted that an attempt at becoming more attractive to the opposite sex and enhancing a girl's likelihood to marry well is part of it, that's the thing — it's just part of the story.

Fordham University questioned why women in poor or rural communities were willing to go through the pain of foot binding and risk disability and death. They say that some estimates suggest about ten percent of the girls who went through the process didn't survive. And poor communities, they say, "could not afford the luxury of helpless women." So, why do it?

Researchers have found (via The Atlantic) another motivation: economic gain. While photographer and historian Jo Farrell found (via The Guardian) that some of the women who had the procedure done got around perfectly fine, others suffered "debilitating, lifelong physical effects." And that may have been the goal, as a girl who had her feet bound was more likely to stay at home and engage in the sort of work that would have made a major economic contribution to the family, like making crafts, processing tea, and spinning cotton. It makes sense, then, that the process was also about economics — and not just beauty.

Some women were able to unbind their feet, but damage had already been done

Putting an end to the practice of foot binding proved difficult. When the Qing Dynasty came to an end in 1912 and the Nationalists established their republic, The Wall Street Journal says they also outlawed the practice. By 1928, though, 18 percent of women reported having bound feet, and it remained a common practice in Yunnan.

When the Communist government took over in 1949, they added a stigma to foot binding and pressured families to stop the practice and even reverse it. Women were encouraged to unbind their feet and burn the bindings, and some — like Pi Guiqiong — were able to. She got married when she was just 15 years old, and while her husband originally told her that he liked her beautiful, tiny feet, he later encouraged her to unbind them. It was a big decision — the elders in the village told her that the ban was just a temporary thing and that she'd regret it, but she unbound them anyway, and eventually, the swelling and pain went away.

Under Communism, women with bound feet — who usually couldn't go outdoor work or walk as fast as others — were shamed. Still, The Guardian says that for many who did finally unbind their feet, they found the damage was permanent.

Foot binding persisted long after it was outlawed

When The Wall Street Journal spoke with Wu Liuying about foot binding in 2009, the then 90-year-old explained: "When the Nationalists came here we would undo our feet in the daytime. Then, at night, we would bind them again."

She wasn't alone: The practice lasted for a long time after it was officially outlawed. NPR spoke to some women who — with the help of their mothers — went out of their way to trick government inspectors into thinking that they were complying with the law.

"When people came to inspect our feet, my mother bandaged my feet, then put big shoes on them," Zhou Guizhen recalled. "When the inspectors came, we fooled them into thinking I had big feet." She continued: "I regret binding my feet. I can't dance, I can't move properly. I regret a lot. But at the time, if you didn't bind your feet, no one would marry you."

Even into the 1960s and 1970s, The Telegraph says government officials would inspect women's feet — if they were found to be wearing bindings, they'd take them off and hang them in the windows as a mark of shame. And that means it's a tradition that's been changing women's lives for at least a thousand years.

Foot binding caused a lifetime of pain and problems

According to The Atlantic, there's long been a massive gap in our knowledge of foot binding, and that's the long-term consequences. Foot binding essentially forces a person to walk not on their whole foot but on only the heel bone and the big toe, which changes gait and posture. But what does that mean as a woman ages?

In 1991, University of California professor Steve Cummings headed to Beijing. He wanted to find out why Chinese women had fewer hip fractures than their similarly aged American counterparts, and the second study participant was the first woman he had ever met with bound feet. After first assuming it was rare, he saw more and more study participants with bound feet and realized there was something else at work.

When he investigated further, he found that women with bound feet were much more likely to have fallen than those without, but at the same time, Chinese women overall had a lower rate for fractures for one simple reason: They rarely left the house. "The way these women avoided injury," he wrote, "was by not doing anything."

He found other problems, too: Women with bound feet tended to have a lower bone density in their spines and hips, more trouble getting up and down from a seated position, and severe difficulties when it came to managing things like a cane at the same time as, say, a shopping bag. Consequences, he found, were lifelong.