The Untold Truth Of 60 Minutes

There are long-running television institutions — The Simpsons, Monday Night Football, Survivor — and then there's 60 Minutes. Since 1968, television's most highly regarded news and information show has provided in-depth coverage of events, politicians, celebrities, and the world at large through impeccable research, thorough and insightful interviews, and all with reporting standards that aim to be both tough and fair. Each episode begins with a now-iconic ticking clock before giving way to a variety of stories both heavy and light, all delivered by veteran correspondents. Among the news luminaries who at some point have worked for 60 Minutes: Mike Wallace, Dan Rather, Diane Sawyer, Anderson Cooper, Ed Bradley, Morley Safer, Lesley Stahl, and Steve Kroft. They all helped pioneer and perfect broadcast journalism, specifically investigative reporting, all to a weekly audience of millions.

Producing such a high-end news show week after week, year after year, and making itself part of the fabric of American life, is the kind of thing deserving of a profile on a show like 60 Minutes. Until the show turns its probing reporters and all-seeing cameras onto itself, here are some off-screen stories about the creation, production, and impact of 60 Minutes.

Don Hewitt created 60 Minutes

Former newspaper editor Don Hewitt joined CBS's news department in 1948, and by 1963, he'd become executive producer of The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. A couple of years later, he'd been relegated to making serious, long-form news documentaries. "I did a series of Town Meetings of the World, in which we linked up world statesmen on the satellite. You could fall asleep in the control room," Hewitt told the Television Academy. At one point, he saw that the documentaries pulled in about 10 percent of the TV audience and he started thinking about ways to double it. "I came up with an idea: make the hour multisubject to deal with people's attention spans, package reality as attractively as Hollywood packages fiction, and use very personal journalism," Hewitt concluded.

According to Vanity Fair, Hewitt developed the idea further with another inspiration in mind: Life magazine. The mid-century publishing phenomenon used bold, striking, and large photographs (along with extensively researched copy) to tell a mixture of stories both serious and light. (In a press release, Hewitt said, "The subjects might be anarchy in the cities, Charles De Gaulle, mini-skirts, or Robert Kennedy.") Hewitt aimed to make a television version of Life, combining visuals with compact, insightful storytelling. Thus, the first "newsmagazine" on TV was born. 60 Minutes followed a magazine format, and still does to this day, presenting segments as chapters and using a magazine cover mockup as its logo.

60 Minutes didn't do well at first

60 Minutes is an integral part of millions of Americans' Sundays, right up there with football and big dinners. The program debuted on September 24, 1968 — a Tuesday night, and in a 10 p.m. timeslot. After correspondent Harry Reasoner gave an introduction explaining the idea of 60 Minutes, "a kind of a magazine for television, which means it has the flexibility and diversity of a magazine adapted to broadcast journalism," the show presented footage of that year's presidential nominating conventions, a piece on police brutality, and the Saul Bass short film "Why Man Creates." (Notably absent: the famous "ticking clock" at the top of the show.) CBS was so unsure if this new TV format — an hour used to tell multiple news stories —would work that 60 Minutes didn't even get to air every week. It alternated the Tuesdays at 10 segment with the more traditional CBS News Hour.

60 Minutes failed to place among even the top 50 most-watched TV shows of the season and went similarly unnoticed for a few years until CBS moved it to 6 p.m. on Sunday evenings — before primetime — in 1971. In 1975, a rule change by the Federal Communications Commission gave the 7 o'clock hour, previously given over to local stations as a way to encourage non-network programming, back to the big broadcasters, provided they use the time for public affairs or news shows, per the New York Times. CBS put 60 Minutes in that spot, where it's remained ever since as a ratings juggernaut.

60 Minutes is the most popular TV show ever. Really.

A lot of factors are at play, but the math doesn't lie: Technically, 60 Minutes is probably the most successful American television show of all time. It's been on television since 1968, and since 1975, in virtually the same time slot, right around Sundays at 7 p.m. in most of the country. It's one of the longest-running programs in primetime television history with 52 seasons thus far.

Also, since it's entrenchment on Sundays, 60 Minutes never fell lower than the top 10 in Nielsen's rankings for 23 consecutive seasons. Also, 60 Minutes was the overall #1 show on TV five times, a feat matched or surpassed by only All in the Family, The Cosby Show, and American Idol. (60 Minutes consistently high numbers do owe something to the fact that on the East Coast, it starts immediately after Sunday afternoon football games, but when it isn't pigskin season, 60 Minutes still rates highly.) Another quantifiable measure of success: awards. As of 2020, 60 Minutes is the recipient of more than 130 Emmys Awards for television excellence — no TV show has ever won more. The show offers such compelling storytelling that in 1979, 60 Minutes earned a nomination for Best Television Series — Drama at the Golden Globe Awards. Amazingly, it won.

60 Minutes was Mike Wallace's baby

The legacy of and style of 60 Minutes is closely tied to Mike Wallace. One of the show's original correspondents upon its debut in 1968, Wallace had worked as a newsman, as well as an actor, announcer, game show host, and pitchman, before re-devoting himself to journalism after his 19-year-old son, Peter, died in a mountain climbing accident. "He was going to be a writer, and so I said, 'I'm going to do something that would make Peter proud,'" Wallace told the New York Times. Wallace quickly earned a reputation as one of the fiercest and most audacious broadcast journalists, unafraid to ask hard questions or even ambush his subjects with a camera crew when they didn't expect it, part of a style that came to be known as "gotcha journalism."

Wallace got the Shah of Iran (prior to the Iranian Revolution of the late '70s) to admit to executing his political adversaries, asked assisted suicide doctor Jack Kevorkian if he was "engaged in a political, medical, macabre publicity venture," and nailed General William Westmoreland for failure to disclose pertinent military information during the Vietnam War. (The General sued CBS and Wallace for libel, and it led to severe depression for the reporter.) Wallace even helped run a phony Chicago medical clinic in the mid-'70s to expose Medicaid corruption. Around the time of his 88th birthday in 2006, Wallace retired from his regular duties at 60 Minutes. He passed away in 2012.

60 Minutes freed a wrongfully convicted man

Reporting is delivering the pertinent information about a news story, as it's made available and discoverable, to the public. Investigative journalism, as performed on a large scale by 60 Minutes, is about probing deep to seek out information — to expose truths, ask questions, and even affect change. In 1983, 60 Minutes' Morley Safer filed an investigative piece that led to the exoneration of a wrongfully convicted man.

The subject of "Lenell Geter's in Jail" was Lenell Geter, an engineer sentenced to life in prison for his role in a 1982 armed robbery of a Balch Springs, Texas, Kentucky Fried Chicken. Safer and his team uncovered numerous inconsistencies and flaws in local police's handling of the case, suggesting everything from poor detective work to racial bias (Geter is African-American) led to a wrongful arrest. When a highly visible media outlet like 60 Minutes takes notice, other outlets do, too, and so much attention came down on Geter's case that by December 1983, his case was reopened. In March 1984, after he'd served more than a year in prison, a court ruled that Geter was innocent and he was given back his freedom.

60 Minutes helped send a man to prison

As exemplified by Mike Wallace's "gotcha journalism," 60 Minutes crews will use whatever tactics it can get away with to reveal misdeeds and illegal behavior. In a 2010 segment, 60 Minutes produced a feature on the modern-day equivalent of snake oil salesmen — self-proclaimed experts selling phony, scam cures derived from stem cells for a number of serious ailments, from cancer to autism to multiple sclerosis.

One such "charlatan," per 60 Minutes: Lawrence Stowe, who ran Stowe Biotherapy in La Mesa, California (according to the Times of San Diego). Stowe, along with accomplice Francisco Morales, offered patients hope in the form of expensive, unproven, and untested stem cell treatments for their fatal or degenerative medical conditions. 60 Minutes caught Stowe in the act of claiming he had the cures for ALS, cancer, and other diseases — by videotaping him on hidden cameras and recording him with hidden microphones. Federal investigations resulted after the 60 Minutes exposé, and Stowe was arrested. He pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy to sell misbranded and unapproved drugs and was sentenced to 78 months in federal prison. (Morales received a five-year sentence.)

The many spinoffs of 60 Minutes

60 Minutes is like any long-running TV show that does well in the ratings year after year. Naturally, its network has sought to replicate its success more than once by ordering up spinoffs. As Cheers birthed Frasier and Happy Days begat Laverne and Shirley, the 60 Minutes format has been adapted and repeated many times since the 1970s. From 1978 to 1982, CBS's Saturday morning lineup included 30 Minutes, a newsmagazine show focusing on topics important to kids.

In 1997, CBS launched what was ultimately a short-lived cable network called CBS Eye on People. Essentially 60 Minutes-style, newsmagazine programming 24-hours-a-day, its signature show was the nightly 60 Minutes More, wherein correspondents from the mother show gave updates on what happened to the subjects of some of their most famous reports. Two years later, when NBC programmed its very 60 Minutes-like Dateline five nights a week, CBS responded with more of the original flavor, creating 60 Minutes II, also known as 60 Minutes Wednesday. 60 Minutes also got in on ill-fated Quibi, which promised super-short programming. The six-minute show 60 in 6 was canceled, along with the rest of Quibi, six months after its launch in 2020.

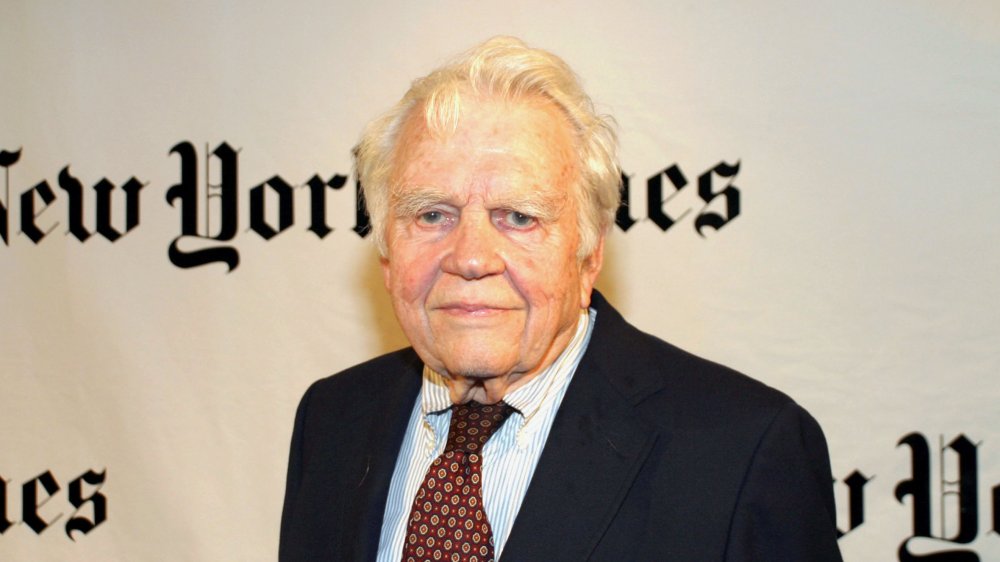

All this, and Andy Rooney

Perhaps the most polarizing feature in 60 Minutes history: "A Few Minutes with Andy Rooney." In 1978, broadcaster and essayist Rooney joined the show to offer three minutes or so of commentary about whatever it was that was aggravating Rooney that week. Topics were generally trivial, and Rooney would crankily complain about it. Initially a replacement for the debate feature "Point/Counterpoint" during summer episodes, it soon usurped that segment's end-of-the-show spot as viewers loved hearing Rooney grumble about nonsense. But as Rooney always spoke his mind, he'd occasionally make an extremely controversial statement. In 1990, he made comments that suggested Black people were less intelligent than other races and he was suspended for three months, a punishment reduced to one after 60 Minutes' ratings fell. That same year, Rooney was suspended for three months again after he said that "premature death" resulted from addiction, overeating ... and "homosexual unions." After Rooney left the air, 60 Minutes viewership dropped quickly and significantly, and so the show welcomed back the commentator, who apologized profusely.

After the death of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain by suicide in April 1994, Rooney was irritated that the news drew more attention than the April 1994 death of President Richard Nixon, that he doesn't understand people who believe "the nonsense about how terrible life is," and dismissed Cobain as a lazy man with a "drug-infested life." A week later, Rooney apologized on the air, mentioned that he should have considered Cobain's history of mental illness.

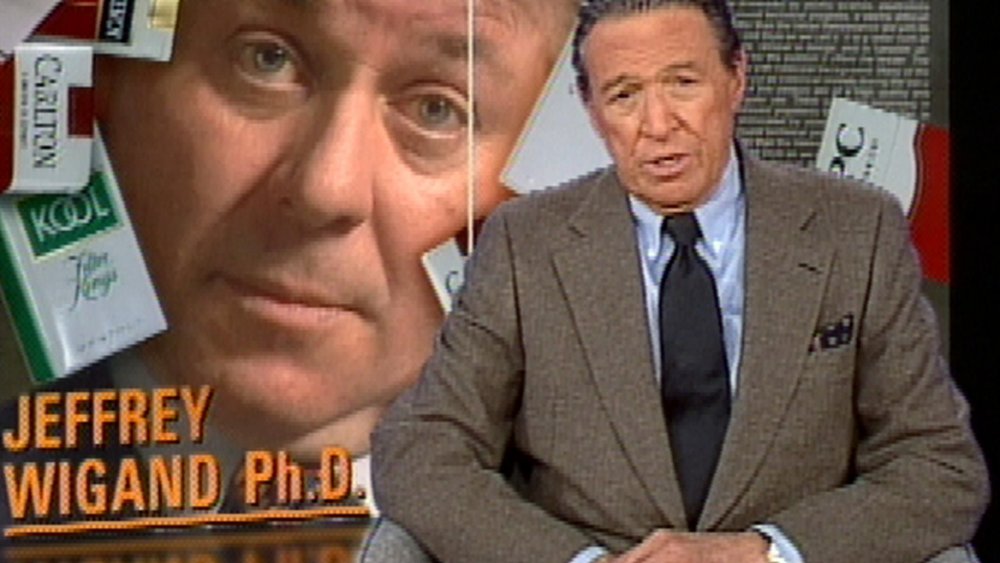

60 Minutes vs. big tobacco vs. CBS

Lots of popular TV shows are made into well-received movies: The Fugitive and Dragnet, for example. 60 Minutes got the big-screen treatment, too, of sorts. The Insider, a 1999 Academy Award nominee for Best Picture, is the dramatic retelling of one of the newsmagazine's messiest and most scandalous moments. In 1995, Jeffrey Wigand, a former researcher with tobacco company Brown & Williamson, who was fired earlier from his job helping to develop a safer cigarette, sat for an interview with 60 Minutes. Contrary to what seven tobacco company executives said in congressional hearings, that the nicotine in cigarettes is non-addictive, Wigand said that his employer knew for years (including from research he'd been a part of) that tobacco smoking was extremely detrimental to human health, and they'd stifled and downplayed that information.

However, Wigand had signed a non-disclosure agreement with Brown & Williamson, which put the 60 Minutes story into murky legal water. Anticipating a potential, legitimate, multi-billion-dollar lawsuit by Brown & Williamson, 60 Minutes producers' bosses at CBS ordered them to kill the story and not air the Wigand interview. After The Wall Street Journal reported on the corporate interference that prevented 60 Minutes from exposing other corporate interference in January 1996, 60 Minutes aired it in full a week later.

60 Minutes interviews are a big deal

Sometimes 60 Minutes doesn't just report the news (and the finer nuances of a story), it makes news itself when it lands potentially bombshell-dropping interviews with prominent public figures in the midst of controversy or on the verge of cultural dominance. (It's arguably in newsmakers' best interests to submit to 60 Minutes reporters' rigorously researched and hard-hitting line of questioning — the show has a pristine journalistic reputation and is regularly viewed by tens of millions of regular Americans.)

On January 26, 1992, millions remained tuned in after CBS's coverage of the Super Bowl for a quickly-produced Steve Kroft interview with Arkansas governor Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, on a 10-minute edition of 60 Minutes. A lounge singer named Gennifer Flowers told a tabloid that she'd carried on a 12-year affair with presidential primary candidate Clinton, and so he and his spouse refuted the allegations on TV. The 60 Minutes interview rocketed both Clintons into the consciousness and rescued their aspirations.

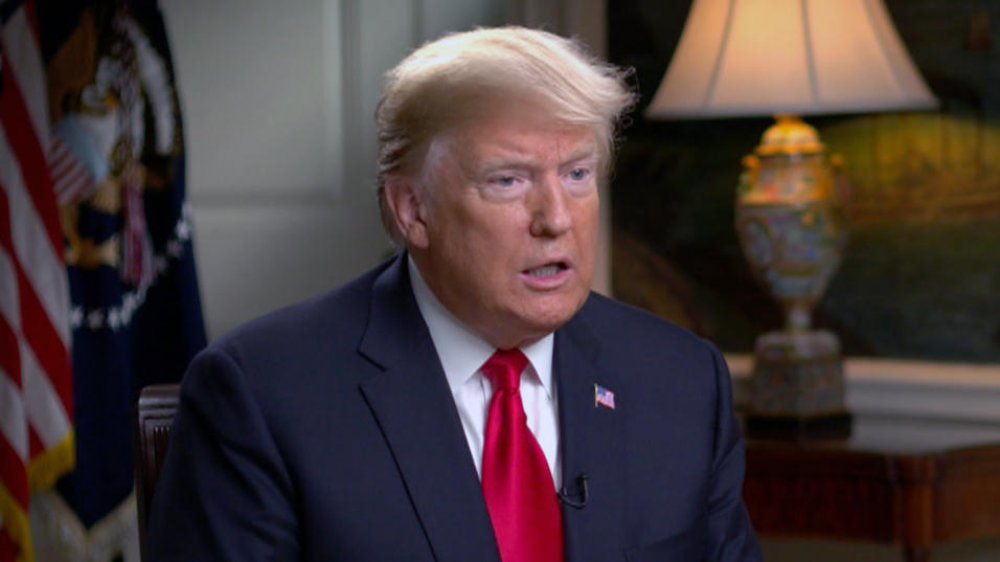

Bill Clinton went on to win the 1992 presidential election while Hillary Rodham Clinton presaged her own political career and public life, memorably telling the world that she's not "some little woman standing by my man like Tammy Wynette." Among 60 Minutes other most-watched interviews: The first post-2008 election sit-down with President-elect Barack Obama and his spouse, Michelle Obama, and Anderson Cooper's 2018 session with adult film star Stormy Daniels to discuss her alleged affair with President Donald Trump.

60 Minutes vs. Donald Trump

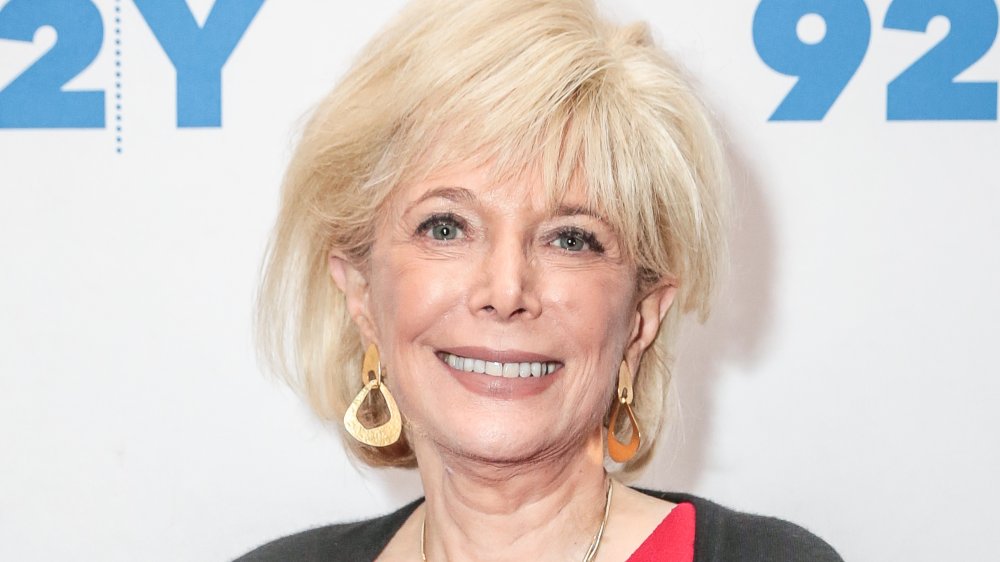

The reporters of 60 Minutes often speak truth to power, but rarely have they ever been engaged in a feud with a sitting American president. In October 2020, the CBS News show prepared an episode set to feature interviews with all four candidates from the two major party tickets: Donald Trump, Mike Pence, Joe Biden, and Kamala Harris. Correspondent Lesley Stahl's sit-down with President Trump at the White House lasted about 45 minutes, according to CNN.

Stahl corrected and fact-checked the president on a few occasions, telling him "you know that's not true" after he boasted that he'd created "the greatest economy in the history of our country" and pointing out that coronavirus infection rates were "up in about 40 states" after he claimed his administration had "done a great job with COVID." Finally, an increasingly frustrated Trump walked out of the interview. Shortly after, as a way to scoop 60 Minutes, the Trump administration released unedited video footage — recorded by a different crew at the White House for official archival purposes. CBS went ahead and aired the 60 Minutes package a few days later.