The Fascinating Story Of 19th Century Paleontologist Mary Anning

The history of science has many hidden stories. The achievements of women in the sciences have often been quietly swept under the rug, especially once we venture further back into history. Yet, with a little digging, we can help bring to light the achievements of those who have contributed to the sciences.

Mary Anning's story was seemingly lost for decades. According to Britannica, she was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, a resort town on the southwestern coast of England. The Anning family was often subject to intense hardships like poverty, disease, and discrimination on the basis of their religious belief, but there was a respite: the seashore.

Not only was the shoreline near Lyme Regis a sometimes pleasant place to walk, depending on the exact stretch of beach, but it was a scientific gold mine. As waves beat at the cliffs, fossils millions of years old were exposed. Those brave enough to venture to the base of these unstable rock formations could uncover scientific treasures. Also, tourists loved to see what could be uncovered here. Fossil hunting became a popular pastime and income stream for many. According to the Lyme Regis Museum, visitors might purchase spiral-shaped ammonites, belemnites, and even coprolites, which are bits of fossilized fecal matter.

Fascinating as coprolites may be, there were bigger things waiting in the cliffs of Lyme Regis. Anning, who devoted most of her life to uncovering and preparing fossils, found some of the most astounding ancient creatures ever revealed in Britain.

Mary Anning's home town was already famous for fossils

Mary Anning was born in Lyme Regis, in a part of southwest England known as the "Jurassic Coast" for its rich fossil deposits. According to the Jurassic Coast Trust, the coastline is made up of many different rock layers deposited over the course of more than 250 million years. Over time, the changing landscape and especially the crashing waves of England's southern coast have eroded this record, creating a unique chance for scientists to uncover fossils from the cliffs without the kind of extensive excavations used elsewhere. It's such an important scientific and historic place that, in 2001, it was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Though UNESCO wasn't around in the early to mid-19th century, many people already understood that the Jurassic Coast was a place rich with scientific possibility. It was also an opportunity for some to make their living. According to the National History Museum, Anning's father, Richard, sometimes collected and sold fossils to supplement the family income. Though he worked more formally as a cabinetmaker, the poverty-stricken family was in need of as much income as they could scrape together. By the time Anning was only about 6 years old, she was already acting as her father's fossil hunting assistant.

The Anning family was in a tough situation

The Annings were set apart from the rest of Lyme Regis, and not in a good way. For one, Anglican and Episcopal History reports, they were religious dissenters. That meant that Mary Anning's parents, Richard and Molly, had split from the Church of England. The family wasn't totally isolated in their belief, as they attended an Independent Chapel in town patronized by other dissenters. However, various laws at the time made it difficult for "Congregationalists," as they soon called themselves, to fully participate in British life. Oftentimes, they were barred from attending universities, were deemed unhireable by some, and couldn't even legally register births or marry in any church other than one run by the Church of England.

Mary Anning's family was also markedly poor. It seems as if they were always teetering on the edge of total ruin, staring the specter of the grim Victorian workhouse in the face. Things grew even more precarious when Richard died in 1810, aged only 44. According to The Fossil Hunter, he was probably done in by a combination of tuberculosis and a fall down one of Lyme Regis' perpetually crumbling cliffs. He left behind £120 in debt, a pretty considerable sum for the time, and especially for the now-alone Molly. This was undoubtedly hard for the then-pregnant Molly, who not only lost her husband but would lose all her children but Mary and Joseph, the only two who made it to adulthood.

Mary Anning taught herself science

Like many other women and poor people of the 19th century, Mary Anning didn't have access to higher education. However, she taught herself subjects like geology and anatomy, becoming so well-versed that she could easily communicate with the top scientists of her time.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the intellectually voracious Anning taught herself subjects relevant to her rambles along the Jurassic Coast, including geology, anatomy, paleontology, and scientific illustration. Her precise drawings of her fossil finds show that she was a careful student who made sure to take down the fine details of her ancient finds.

Anning did such a good job educating herself that she could comfortably write to more famous scientists of her time. These included William Buckland who, according to The Fossil Hunter, was a famed theologian and paleontologist who wrote the first report of a fossil dinosaur. She also corresponded with Richard Owen, who was the one to come up with the word "dinosaur" in the first place. In September 1839, says The Fossil Hunter, Owen made his only visit to Lyme Regis specifically to speak with Anning.

Mary Anning made groundbreaking fossil finds

Though Mary Anning would struggle throughout her life to get the full recognition she deserved for her work, the fact remains that she uncovered beautifully preserved specimens of ancient life, all while working in perilous conditions under Lyme Regis' crumbling cliffs.

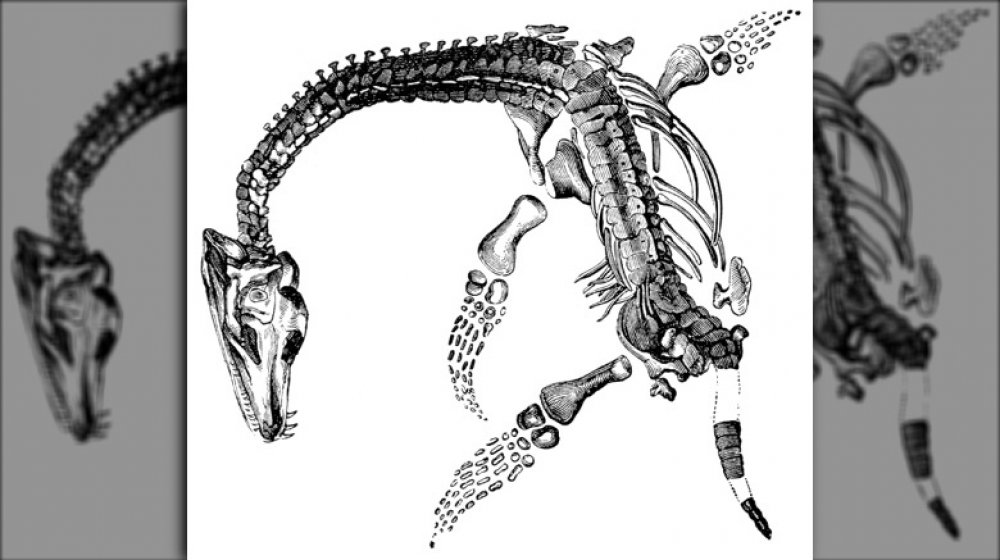

She started while she was quite young. According to the National History Museum, Anning excavated the first known Ichthyosaurus fossil around 1811, when she was only 12. Her brother, Joseph, had been the first one to spot the creature's extraordinary-looking skull, but Anning was the one who put in the work to uncover the animal's estimated 17-foot-long skeleton.

In 1824, she became most famous for finding the first full Plesiosaurus skeleton in the same area around Lyme Regis, says Britannica. It was in such good condition that a number of scientists became immediately suspicious of her find. Could Anning have faked it? Even Georges Cuvier, the very well respected French zoologist, wasn't sure until he saw detailed drawings of the specimen. He authenticated the find and vindicated Anning, leading to her wide renown as a skilled fossil hunter. Soon enough, tourists and scientists were traveling to Lyme Regis to see Anning and her fossil finds.

Mary Anning wasn't always given credit for her finds

In the early to mid-19th century, you could be pretty easily misled by the labels on a museum display. Often, the person who purchased and then donated the fossil was the one who got to see their name in print, says the BBC. Mary Anning and other people who did the actual work of digging these finds out of the ground, describing them, and getting the word out rarely got the sort of credit they deserved.

Even Sir Richard Owen, the well known and highly respected scientist who regularly corresponded with Anning, wasn't above sweeping her name under the rug. According to The Fossil Hunter, Owen presented her work on the Plesiosaurus skeleton she'd uncovered, giving a ton of detail, without ever actually mentioning her name. It was standard practice at the time to give the working class fossil hunters the cold shoulder, though the field would be nothing without them. Still, it's a terribly bad look today.

Mary Anning found the first pterosaur outside of Germany

In 1828, Mary Anning found what, upon first evaluation, looked like an odd jumble of bones. Anning, with her self-taught but still considerable knowledge of paleontology and geology, knew that these were fossil remains. But, it took some careful evaluation and the help of other scientists to understand just what a big deal this find would become.

As per the Lyme Regis Museum, Anning asked scientist William Buckland what he thought these bones were supposed to be. Buckland had already seen hollow bone fragments from other deposits and recognized that this could be the same type of animal.

According to The Fossil Hunter, Anning and her fellows first called this specimen a Dimorphodon. Eventually, that was amended, and it became clear that Anning had uncovered the first pterosaur fossil found outside of Germany. They first appeared about 200 million years ago, long before the first bird evolved from a dinosaur species. Anning produced sketches of this find using ink harvested from fossil cephalopods called "belemnites."

Pterosaurs are pretty fascinating finds for paleontologists even today. These "winged lizards," as their Latin name translates, aren't actually dinosaurs, Smithsonian Magazine says. Pterosaurs, like the massive Quetzalcoatlus, share a common ancestor with dinosaurs, but they're a distinct group of species.

Tourists loved to visit Mary Anning's fossil shop

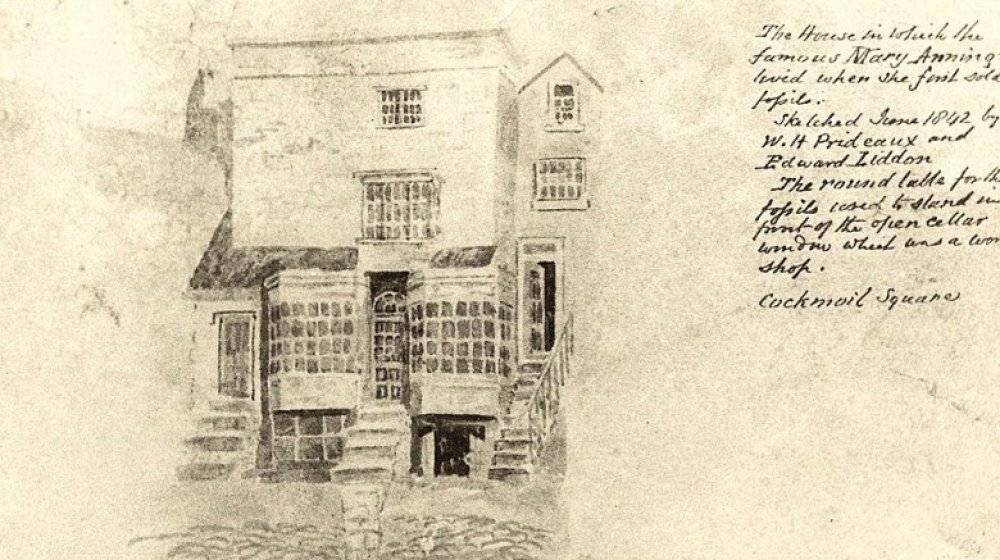

Though she didn't always get credit for her finds, Mary Anning was well-known enough that she became a tourist attraction herself. Visitors to Lyme Regis often dropped into her fossil shop to see her, though, given Anning's shaky finances, they didn't buy as many fossils as they should have.

These visitors were often of a social class considered to be above Anning's own. As per the Geological Society, Lady Harriet Silvester deigned to visit Anning on Sept. 17, 1824. In her diary, she wrote that "It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour — that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed ... they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in the kingdom."

According to Jurassic Mary, Anning proved to be a pretty lucrative figure for the local tourist industry. Though her home and shop no longer stands, its site is now given over to the Lyme Regis Museum, a 113-year-old institution with plenty of exhibits on their long-gone resident and even a new expansion named the Mary Anning Wing.

The first work of paleoart was sold to help Mary Anning

Throughout her life, Mary Anning struggled with money. According to the BBC, horrific poverty throughout the Victorian era was a very real possibility for many people. It wouldn't be until the end of the century that conditions improved for the working class. Until then, it could take only a few unfortunate circumstances or a rough start in life to keep someone in unsteady finances for a very long time. Anning, born into poverty and denied the chance to get formal education, was arguably one such victim of these tough social conditions.

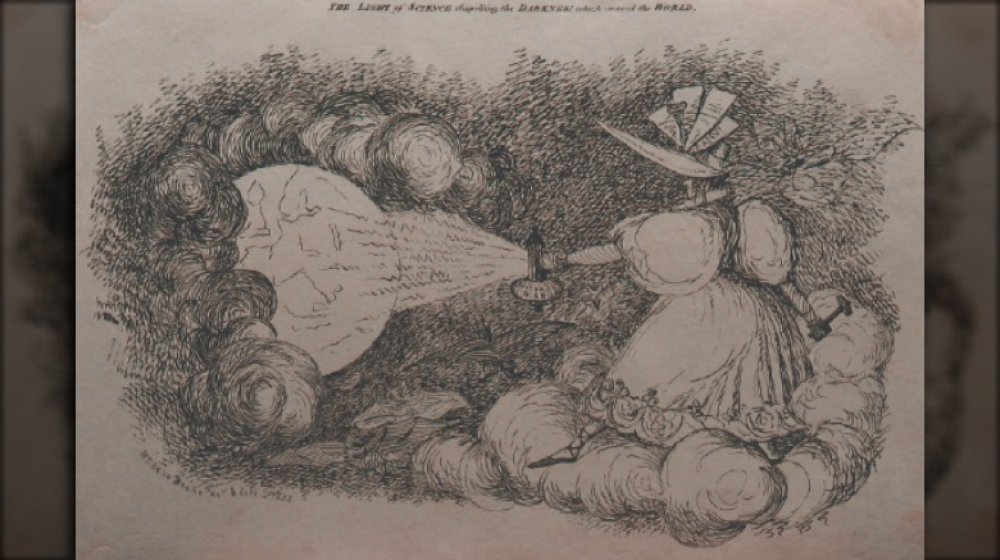

She wasn't without a safety net, however. Her childhood friend, geologist Henry De la Beche, often championed Anning's work. To help support her and bring more attention to her work, De la Beche painted a watercolor he titled Duria Antiquior or Ancient Dorset. According to The Dragon Seekers, this was the first piece of evidence-based art to show what the Jurassic Coast may have looked like. It is a dramatic scene of aquatic and flying animals, with an Ichthyosaur snapping at the neck of a Plesiosaur and various fish hunting each other.

Sales of prints went to help Anning, says The Fossil Hunter, who used the income to supplement the profits from her small fossil shop. Thankfully, it was a popular piece of art, used by intellectuals and members of the public to think more deeply about the ancient world before humans made their debut.

Classism held Mary Anning back

Mary Anning was born into a world that was, in many ways, fixated on hierarchy. According to Britannica, the two factors that most determined someone's place in the world of Victorian Britain were one's gender and class. As a woman, Anning already had a mark against her, socially speaking. Traditionalists believed that women like Anning should stay in the private realm of the home, occupying themselves with childrearing and other domestic duties.

Her class was another major factor that held her back. According to The Conversation, science wasn't merely a male-dominated sphere but one that also hinged on class. The prevailing thought was that gentlemen could be scientists, but the working class folks who unearthed fossils were merely laborers who couldn't comprehend the true value of their finds. Anning, who could not sit easy on a family fortune or gain access to intellectual organizations, had to work for her well-being and therefore tainted her finds, at least to some minds.

Anning was doomed to be seen as an amateur by the most class-conscious Victorians, though at least she had friends like Henry De la Beche who were willing to defend her. As per the BBC, De la Beche read a eulogy for her to the Geological Society of London, after Anning's death in 1847. He wrote that Anning, "though not placed among even the easier classes of society ... contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge."

We know almost nothing about Mary Anning's personal life

Mary Anning left behind very little personal information. Unlike other historic figures, she isn't known to have kept a diary or written anything more revealing than a few letters, many of which were more professional than personal.

Some of those letters do reveal something of her inner workings. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she wrote that "The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone." What that meant for her personal life remains pretty mysterious. We know for certain that she never married, and there's no hint that she ever carried on a romantic relationship with anyone. She did form friendships with other women, including her fellow fossil hunter, Elizabeth Philpot, TrowelBlazers reports.

Could she have been a secret lesbian, as the 2020 film Ammonite proposes? If she were anything other than heterosexual, chances are good that Anning would have hidden this part of herself in what was undeniably a homophobic society. Yet, as The Guardian points out, there's no concrete evidence of anything about Anning's sexuality. There's definitely nothing that says her friendship with fellow fossil hunter Charlotte Murchison was anything other than platonic. That truth will likely remain forever buried.

Mary Anning wasn't the only woman digging up fossils

Though she often worked alone on a day-to-day basis, Mary Anning was actually part of a small but enthusiastic group of female fossil hunters. Their camaraderie likely provided at least some comfort and encouragement to Anning as she continued with her own career.

Anning was preceded by Elizabeth Philpot, who settled in Lyme Regis with her sisters around 1805, according to TrowelBlazers. Philpot, along with her siblings Mary and Margaret, lived in the town for the rest of their life, soon becoming enthusiastic fossil collectors. As their collection and recognition grew, they came into contact with the younger Anning. From the letters exchanged between them, it's clear that Anning and the Philpot sisters developed a close friendship.

Anning is also known to have worked alongside Charlotte Murchison. As per TrowelBlazers, she was the wife of Roderick Murchison, himself a budding geologist. Charlotte, who suffered the effects of a bout with malaria for the rest of her life, was rarely in good health. This may have been why the couple took a trip to Lyme Regis in 1825. There, Charlotte collected and sketched fossils, in the process befriending Anning. Later, she would be credited with helping to open college geology lectures to female students, who were previously barred from attending. Charlotte, whose historical record is often overshadowed by her husband's career, was an accomplished scientific illustrator in her own right who saw some of her work published during her lifetime.

Mary Anning's name went all the way to Mars

In 2020, the team operating the Curiosity rover named a drilling site after Mary Anning. According to NASA, this honor was meant to bring more attention to Anning's work as to "remind us to include everyone in the endeavor of exploration."

Ultimately, NASA reports, the site had made 27 drill holes by the time Curiosity moved on. Anning, who had clearly demonstrated that she was an enthusiastic scientist and student, would have already known about Mars and may very well have wondered what the geology of the planet was like. Britannica reports that Mars has been observed for centuries, with the first scientific observations of the Red Planet taking place in the 17th century.

The Curiosity team didn't stop with Anning's name while they were still at the site. According to the USGS, they named a nearby camera target "Tray," after Anning's beloved dog, who often accompanied her on fossil hunting expeditions.