Mysterious Fossils Science Still Can't Explain

Fossils capture the imagination, giving us a glimpse into the distant past. They've given us our most comprehensive looks at long-extinct plants and animals, and helped us understand how life on our planet has evolved and adapted over millennia.

But some fossils have raised more questions than answers. While many of the more mysterious specimens have been explained away by now — sometimes forcing us to rethink the timeline we've pieced together for the development of life on Earth — a few remain a total enigma, with theories ranging from missing-link humans and sea-floor cacti to microscopic life forms from outer space. From strange aquatic creatures that don't seem to fit into the tree of life to the earliest records of life on Earth, here are some of the fossils that scientists just can't explain.

ALH84001 (the Martian bacterial fossil)

Countless science fiction stories revolve around life on Mars, and more than a few pseudo-scientists have found "proof" of life in odd Martian rock formations and camera glitches. But scientists take possible life on Mars seriously, and actually might have proof in the mysterious meteorite known as ALH84001.

The little meteor fell to Earth in 1984 and seemed like an interesting, albeit normal, meteor sample. With more study, scientists came to a shocking conclusion: The meteor was from Mars and was 4.1 billion years old. It was blown off the planet during a collision and traveled space since then, finally coming down to Earth. Even more shockingly, it had what looked like features of fossilized bacteria in it. Overnight, ALH84001 became the most famous meteor on Earth.

Since then, scientists have debated the nature of the rock. Sure, it looks like there are bacteria embedded in it, but further study has proven inconclusive. It could just be remnants of mineral structures found on Mars all those years ago, or a fluke of geologic formation. What makes ALH84001 so amazing is that, even after 30 years of study, it's still a mystery. Scientists still take it very seriously, with groups even proposing that ALH84001 provides evidence that the moon and other worlds could be "littered with fossils" knocked away from Earth by asteroid collisions. Possibly, the planets are constantly trading rocks through this mechanism, and maybe even trading life as well.

Homo naledi

Since the discovery of early hominid fossils, most researchers focused in small geographic areas where they felt certain they'd find fossils of our ancestors. All that changed in 2015, when researchers in South Africa found hominid fossils that didn't relate to any of the known hominid fossil families. Named "Homo naledi," the fossils were from a new family of human predecessors.

Homo naledi fossils occupy a weird place in the human family tree, falling between hominids and apes both structurally and behaviorally. This has led some researchers to propose that they're not truly hominids, but instead some sort of evolutionary middle child that defies classification. Oddly, the specimen was less than 350,000 years old, meaning it lived right before Homo sapiens appeared. Yet, their bodies are more similar to older hominid specimens. This would be like finding out that neanderthals were still alive somewhere in our world today.

More mysteries crop up when analyzing their behavior. All the fossils were found in a large burial hole, but it seems like the Homo naledi might have just dumped the bodies there without any ritual. All this adds up to a puzzling picture, especially when you consider that this species might have survived up until the development of Homo sapiens. This means that our ancestors probably had contact with small-brained hominids, contrary to what was previously thought, forcing us to re-evaluate the timeline of human development. How Homo naledi developed at all, and whether our ancestors actually interacted with them, is still a mystery.

[Featured image by Berger et al. 2015 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

Tully Monster

Discovered in 1955 by collector Francis Tully, the first Tully Monster fossil completely defied explanation. Paleontologists eagerly attempted to place the fossil within well-known classifications, but nobody could figure out what the "monster" was actually related to.

Looking at reproductions of the monster show why it was so confusing. The main part of the creature had a body like a cuttlefish, with vertical fins sticking off the top. It had no bones in its body, but could keep a rigid shape like mollusks or worms do. Eye pods stuck out from the sides of the body. Most unusually, the monster had a long, segmented proboscis with a "head" on the end. Unlike the proboscis found on animals like butterflies, the Tully Monster's proboscis ended in a set of jaws with teeth. Adding it all up, the Tully Monster looked like something a child would draw.

When trying to set it into classification, researchers were completely stumped about where it fit. They thought it might be related to a worm, mollusk, arthropod, or a conodont. Unfortunately, all those classifications are unrelated to each other. Finally, some samples showed up with a rudimentary spinal cord, letting researchers know that they could at least classify it as an early vertebrate. Aside from that, the Tully Monster remains a baffling evolutionary turn in our planet's history. Researchers are still trying to decide how it evolved and what place it held in the prehistoric ecosystem.

The dinosaur fossils found in the frozen Arctic

When we imagine dinosaurs, we usually picture them in tropical climates, or in the warm oceans. Since most dinosaur fossils are discovered in these types of environments, that image makes sense. But scientists have discovered a new species of dinosaur living in the most unlikely of places: Arctic Alaska.

The new dinosaurs have the fun name Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis, and lived 70 million years ago in the frozen North. The discovery of these duck-billed dinosaurs has created countless questions, forcing paleontologists to completely rethink what they believe about dinosaurs. Since these giant lizards lived in polar climates, they must have created their own heat, undermining the idea that dinosaurs were only cold-blooded creatures. Most likely, their blood systems were much more diverse than originally thought.

But the biggest mystery is how these frigid dinosaurs made it up there in the first place, so far removed from the biggest populations of their scaly cousins. Something had to get them up there, and scientists are hard-pressed to figure out what made them migrate north. Whatever the case, these dinosaurs lived a rough life, combating months of snow and darkness since they lived in the Arctic year-round. With the mystery of their migration, blood chemistry, and the other gnawing question of what exactly they ate in the frozen tundra, Alaska is rapidly becoming the last frontier of paleontology, one of the last places where mysteries about these scaly creatures still abound.

Klerksdorp Spheres

The Klerksdorp Spheres were first discovered in Ottosdal, South Africa, during mineral deposit excavations. The spheres became an intense curiosity among the miners and geologists as more cropped up during the dig. As the name suggests, they're spherical in shape and made out of an extremely hard mixture of metals. Most of the spheres have a groove running around their equator. These spheres' grooves date back to 3 million B.C., which quickly led to conspiracy theories about ancient aliens or highly advanced prehistoric civilizations. The spheres just seemed too perfect for any natural process. Ancient-astronaut theorists quickly latched on to the story and speculated that these were out-of-place artifacts left by aliens.

Of course, party-pooper geologists were quick to shoot down the idea. They pointed out that the fossils could have occurred due to natural volcanic activity. Certain types of volcanic metals are apt to form spherical shapes, and weather could have created the equatorial groves. Geologists point out that spherical rocks are not uncommon, but conspiracy theorists hold onto the idea that the spheres are part of the fossil record of ancient alien contact with the Earth.

Honestly, neither group has an airtight theory about the spheres' origin. Geologists have remained skeptical but have not yet come up with a solid explanation, and ancient-alien conspiracists still cannot explain why aliens would come down to Earth just to scatter metal spheres all over South Africa. That's an awful long route to travel just to relieve boredom.

Godzillus

Amateur paleontologists are often the ones digging up mysterious and surprising fossils. In 2011, Ron Fine and his team found an incredibly unusual fossil just outside of Covington, Kentucky. Finding various chunks with plant-like patterns during a dig, Fine realized they had discovered a broken-up fossil. After excavating the chunks, they reassembled the fossil to reveal its mysterious form. Oblong in shape, the fossil was gigantic, coming in around 7 feet long and consisting of multiple lobes organized in an elliptical shape.

Further research dated the fossil to 450 million years ago, a time when life on Earth thrived in the water. Fine's dig site was underwater during that time, so the team assumed they had found some sort of strange sea monster. The fossil structure was unlike anything paleontologists had seen before. It consists of layers and oblong surfaces, much like a flattened cactus. Fine believes the creature stood up to 9 feet tall (which explains why he and his team named their find Godzillus), and had arms or branches radiating from the side.

Oddly, nobody knows if Godzillus was a plant or an animal. Fine's team theorized that it was a soft-bodied animal, which means 450 million years ago, there were 9-foot-long, slug-like giants wandering our oceans. Others believe it is merely a mat of algae, which sounds far more plausible, but also way less fun.

Homo floresiensis

Discovering new ancestors of modern humans is always fascinating, but sometimes completely baffling. When an Australian-Indonesian team discovered the fossils of a small hominid in 2003, they realized they would open new mysteries and questions about the human family. Indeed, their discovery, named Homo floresiensis, has forced researchers to rethink the human family history and the place of modern humans in it.

The hominid was diminutive, with samples averaging only a little over 3 feet tall, with big feet. Researchers began calling them Hobbits, which caused the Tolkien estate to threaten legal proceedings. Still, the nickname persisted, because what else are you going to call them?

So far, Homo floresiensis has only been found on one island in Indonesia, and records indicate they lived as recently as 50,000 years ago. Since the Hobbits are so close in the timeline to our own species, researchers are utterly baffled by them. Some contend that it's a totally separate species from humans, meaning Homo sapiens were not the only hominid species inhabiting the planet back in ancient times. This completely flies in the face of the old consensus that Homo sapiens were the only hominid species remaining when they took over the world. Others believe that the Hobbits were actually Homo sapiens who settled on Indonesia and, over centuries of inbreeding, developed dwarfism. Oddly, it seems like the second option has captured more steam among researchers, though if anybody digs up a shiny gold ring and dubs it their precious, all bets are off.

Chandra Wickramasinghe's meteorite fossils

Fossils don't just come from underground — now they can come from outer space! On December 29, 2012, a meteorite allegedly fell in Sri Lanka. We say "allegedly" because the International Meteorite Society did not record the impact, yet fringe scientists began studying the meteorite sample anyway, which was in good shape once recovered. While studying the dusty space rock, Chandra Wickramasinghe made a startling discovery: The meteorite had signs of fossilized life.

Wickramasinghe and his team published a paper outlining their discovery of diatom in the sample. These are microscopic phytoplankton that scientists use to monitor environmental conditions from the past. Diatoms preserve extraordinarily well in even the most extreme conditions. Wickramasinghe supposedly found multiple samples in the meteorite, which were in turn studied by diatom expert Patrick Kociolek, who verified that the microscopic creatures were diatoms, but noted that they shared similar evolutionary traits to diatoms on Earth. That means either the rock wasn't a meteorite, or life out in space took a similar evolutionary route to life on Earth.

Other scientists threw out the claim, believing that lightning actually formed the rock. Another hypothesis came forward that the rock was from both space and Earth, having been blasted into orbit during a bombardment event in the remote past. Among mainstream astrobiologists, Wickramasinghe's results are not taken seriously, but so far nobody has come up with a definitive explanation.

The Nampa Stone Doll

Most people don't think of Idaho as a hotspot for archaeological mysteries, but it's actually the home of a mysterious figure that remains unexplained. The figure was dug up in 1889 when workers were digging a well in Nampa, right outside Boise. Resembling a human doll but made of stone and clay, the figure was buried 320 feet below the surface of the Earth. Finding a stone doll is weird enough — finding it that deep is a spine-tingling mystery.

The rock around the doll dated to 2 million years ago, far before any hominid made it to Idaho. This was also millions of years before Homo sapiens or comparable species walked the Earth, period. Paleontologists believe only Homo sapiens have the ability for this sort of workmanship, but they only appeared 200,000 years ago. Here is a stone doll that was at least a million and a half years older, with ornate designs that were clearly carved by hand. The right arm is even cemented to the doll, showing clear signs of artistic workmanship. This was certainly created by ancient humans who should not have existed at the time.

So, how did it get in the rock? Of course, skeptics have proposed a variety of mechanisms, including that it's fake. If it is evidence of ancient humans in Idaho, it would completely rewrite the evolutionary timeline of humanity, showing that Homo sapiens — or a currently unknown, comparable species — existed way before we expected it. (It could also just be a fake.)

UC Riverside's mysterious circles

In 1986, scientists at the University of California-Riverside found a mysterious rock in Wisconsin, dated to back when the state was covered in water. The rock had mysterious circles on it, raised above the surface and perfectly circular. Scientists studied the weird rock for awhile and then, stumped, filed it away as an unsolved mystery.

Jump forward to 2015, and the fossil was still a mystery. Nobody could explain what could make perfect circles in the sea bed 450 million years ago. At a complete loss of ideas, U.C. Riverside scientists did what scientists rarely do: They opened it up to the internet and asked Reddit users to propose theories. Ideas ranged from sarcastic (typical for Reddit) to shockingly well-thought out. Some theorized that these were the work of prehistoric snails. Others though that jellyfish or sea sponges could have caused the shape. Overall, while the social media involvement was a success in brainstorming possible angles, none of the theories perfectly fit. All we know is what we already knew: 450 million years ago, something was making perfect circles on the seafloor in Wisconsin.

End-Permian mass extinction fossils

Everyone knows that the dinosaurs died out from a giant asteroid collision, but few people know that the dinosaur extinction was not the only — or even the worst — mass extinction that our planet faced. There have been five, with the largest being the end-Permian event, which happened 252 million years ago. It is also the most mysterious. Fossil records show that 95% of all marine species and 75% of all terrestrial species went extinct during the event. The biodiversity loss was catastrophic, and it took millions of years to get back to pre-extinction levels.

But here's the weirdest part: Nobody knows why it happened. You'd think that such a traumatic event in the Earth's history would leave pretty definitive clues about what caused it, but that's not the case. For years, scientists have struggled to figure out why so many species died, seemingly out of nowhere. One leading theory is that intense global warming caused the extinction, leading to wide-scale ocean acidification that was absolutely deadly to marine life.

But other theories are much more exciting. Geologist Gregory Retallack has discovered microscopic fractures in quartz crystals that date from the time of the extinction, implying that some sort of massive force shook the Earth. According to Retallack, it could have been an asteroid collision, just like with the dinosaurs. An even more exotic theory held by many scientists is that coal in Canada and basalt in Siberia might have blown up out of nowhere, causing a huge ash cloud and making almost all life on Earth go extinct.

The Atacama 'alien'

There's no denying this one's weird enough to make the most determined alien denier stop and rethink their position. According to the Smithsonian, a 6-inch-long skeleton was discovered in a Chilean ghost town in 2003. Found in the Atacama Desert, the mummy has been nicknamed "Ata." Despite looking vaguely human, there are other oddities. (Besides, of course, the size.) There's the pointed skull, the giant eye sockets, and two missing ribs. Surely, that's all the proof you need that aliens are real, right? The tiny mummy provided some serious fuel for believers, but in 2018, scientists revealed part of the puzzle.

The mummy's DNA confirmed she is very human, and she's even a local. But researchers from Stanford University kept digging and got more questions than answers. Initially thought to be ancient, scientists eventually determined the remains were only around 40 years old at the time of discovery, according to The Guardian. They also found that, while her skeleton appeared to indicate she was 6 to 8 years old, her bones had probably been prematurely aged by a congenital disorder.

She also had a shocking number of genetic mutations, a list that included variants linked to things like dwarfism and scoliosis. But the list also contained mutations that scientists were confused by — in all, 54 rare mutations that possibly describe diseases and conditions modern science has never seen and can't explain. So Ata isn't an alien, but it might be less weird if she were.

Amphicoelias fragillimus

The late 1800s is known within paleontology as the time of the Bone Wars, when rival scientists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope engaged in a fierce and bitter contest to find and classify as many new fossils as possible. The two men spent fortunes on expeditions to the American West — expeditions prepared to sabotage the other side.

Out of the Bone Wars came the discovery of what Cope named Amphicoelias fragillimus, a long-necked dinosaur related to the genus Diplodocus. Cope described A. fragillimus from a single, incomplete vertebra found somewhere near Cañon City, Colorado. The fragment was measured at almost 5 feet tall, which would make the complete bone 8.5 feet and belonging to an animal 190 feet long (per FiveThirtyEight). Based on that, A. fragillimus has been proposed as not only the largest dinosaur, but the largest known animal to have ever lived next to the blue whale, according to Annals of Carnegie Museum.

But that's assuming the bone was that big, and A. fragillimus really was a diplodocid. Some paleontologists suspect Cope invented the find to get one up on Marsh, though Marsh, never shy on such matters, never challenged it. Others think Cope made a mistake in his measurements. It's recently been reclassified and renamed Maraapunisaurus, with a smaller size estimate. But with the only known bone lost since Cope's time, and no others discovered since, nothing can be said for certain. What even happened to the vertebra is a mystery itself, though it may have simply crumbled away.

Bahariasaurus

The dinosaurs may have been killed by an asteroid, but if some of their fossils have escaped our knowledge, it's sometimes been on account of other objects falling from the sky. In 1911, German paleontologist Ernst Stromer led an expedition into the Bahariya oasis in Egypt. Stromer was unable to stay long, and World War I frustrated any return trip. He was dependent on shipments of fossils back to Germany, and a particularly significant one from 1922 was badly damaged by customs.

From what was left of that shipment, Stromer gradually identified and named three new species of dinosaur. According to William Nothdurft and Josh Smith's book "The Lost Dinosaurs of Egypt," one of them was Bahariasaurus, described from a small number of hip, spine, and rib bones. Stromer connected his new species to fossils he'd first found in 1911 and proposed that Bahariasaurus was a theropod dinosaur of a size to rival Tyrannosaurus rex.

But Bahariasaurus has rarely been noticed by later paleontologists and occupies an uncertain place in the dinosaur family tree. No other remains positively identified as belonging to the species have been found, and a 2020 paper in ZooKeys (via PubMed Central) suggested the name should be folded into another, Deltadromeus. No more answers can be found in Stromer's fossils either. They, and every other fossil from the Bahariya region, were destroyed by objects from the sky — specifically, Allied bombs in World War II.

[Featured image by The Royal Society via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

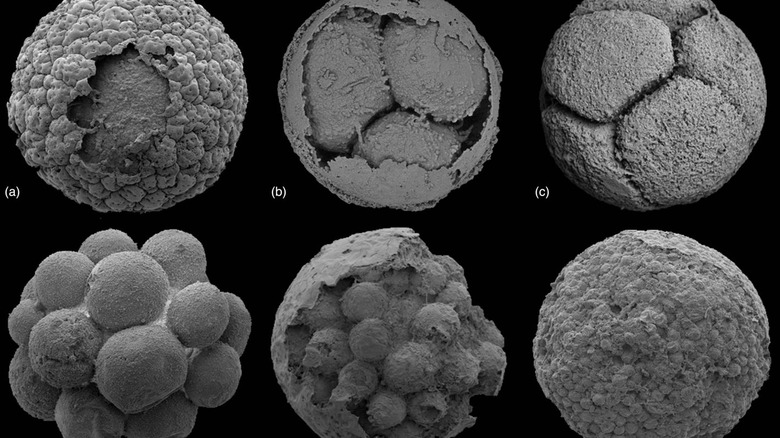

Acritarchs

Paleontology has a large number of what are known as "problematica", fossils that cannot be confidently identified or placed on the tree of life. Whether it's on account of incomplete remains or unusual features that defy easy classification, these plants and animals fill the drawers of museums, awaiting answers.

Many problematica come from very early in the history of life, when a large number of organisms unlike anything alive today existed. There's an entire category designed for such fossils: acritarchs. According to the geosciences department of the University College London, the term "acritarch" was first coined in 1963. Literally translated as "of uncertain origin," acritarch is a catch-all for microscopic fossils that don't fit anywhere else in the evolutionary chain.

It's been suggested that acritarchs represent stages of growth, or organic material discarded from single-cell plants and animals. Whatever they are, the oldest of them date back to 1900 million years ago. Their fossils are some of the earliest records of life.

[Featured image by John A. Cunningham, Kelly Vargas, Zongjun Yin, Stefan Bengtson and Philip C. J. Donoghue via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 3.0 ]

Amiskwia

There's not much mystery around Amiskwia as far as its existence and appearance are concerned. There are multiple species described under the genus, and the fossils we have for some of them are of such high quality that some scientists think an impression of the brain has been preserved. But for how well represented it is in the fossil record, there is one mystery hovering over Amiskwia: What is it?

Amiskwia dates to the middle Cambrian period, some 505 million years ago. If that's not quite the dawn of life, it's still ancient, and it has traits in common with a number of later classes of animal. It's like an arrow worm in some ways, a ribbon worm in others, and a mollusk in still others. A paper published in Nature in 2019 argued that Amiskwia belonged in the clade gnathifera, but the authors couldn't confidently place it within the group, and a later study from 2022 rejected this classification (per the Journal of Systematic Paleontology). Some scientists have even suggested Amiskwia doesn't fit anywhere among still-existing groups of animals, but represents an unknown group that died out completely over time.

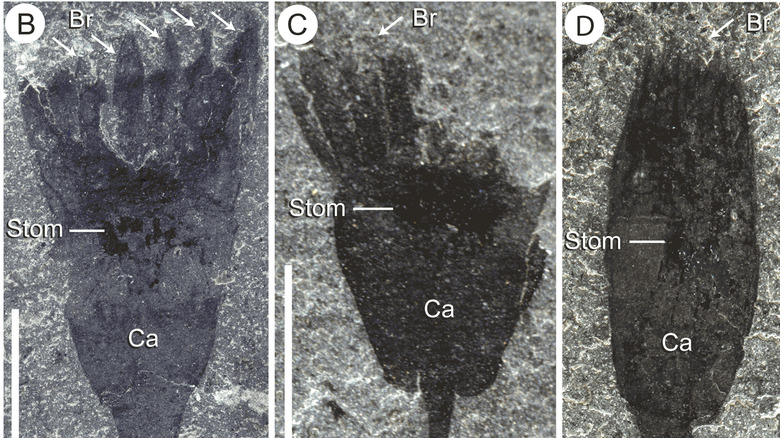

Dinomischus

Among the most prized sources of fossils in the world, particularly from the Cambrian period, is the Burgess Shale of British Columbia. First observed scientifically by paleontologist Charles Walcott in 1907, it's the place where many microfossils have been found and described, including a large number of problematica.

Among the organisms found in the Burgess Shale is Dinomischus, first described in 1977 from a fossil Walcott found decades earlier. To look at it, Dinomischus seems like a flower. But it is an animal, though what kind has been an open question since it was named. We know that it was a species that attached itself to the seafloor and filtered food from the water through the ring around its mouth. Linking to a specific group is frustrated by its superficial similarities to a number of still-living species.

The closest known relative of Dinomischus may not be an extant animal, but another fossil. In 2012, PLOS One (via PubMed Central) published findings from a Canadian team on another stalked filter feeder, Siphusauctum gregarium. Its best match in the known fossil record was Dinomischus. But the two animals' resemblance to one another doesn't help place either one of them confidently in the evolutionary chain. Even the traits they share aren't enough to conclusively prove that they're related.

[Featured image by Lorna J. O'Brien, Jean-Bernard Caron via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

The cat gap in the fossil record

Some fossil mysteries have less to do with an individual specimen than the absence of specimens where paleontologists would expect to find them. Cats and their closest relatives reached the North American continent during the Oligocene epoch, around 33 million years ago. They were represented by the nimravidae, also called false saber-toothed cats. Around 28 million years ago, the nimravids died out. They were succeeded by the barbourofelidae around 11 million years ago, and by direct ancestors of today's cats. But that leaves a several-million-year period where cats and their kin are almost entirely absent from the fossil record of North America.

One proposed explanation for this cat gap is that no one's looking for cat fossils from that time period. Another is that conditions in North America during that time didn't favor fossilization. But other mammal species in North America are well-represented in the fossil record through the cat gap. So what's behind cats' seeming long absence from the continent?

One theory is that global cooling changed large swaths of North America from forest to grassland. This would have seen the nimravids' favored prey die out, according to Chelsea Whyte of New Scientist (via Science Friday). And the new grasslands wouldn't have been the most welcoming to cats from Asia that had various chances to cross into America as land bridges appeared and disappeared over the Miocene. But for some scientists, any explanation from the available evidence is speculative.

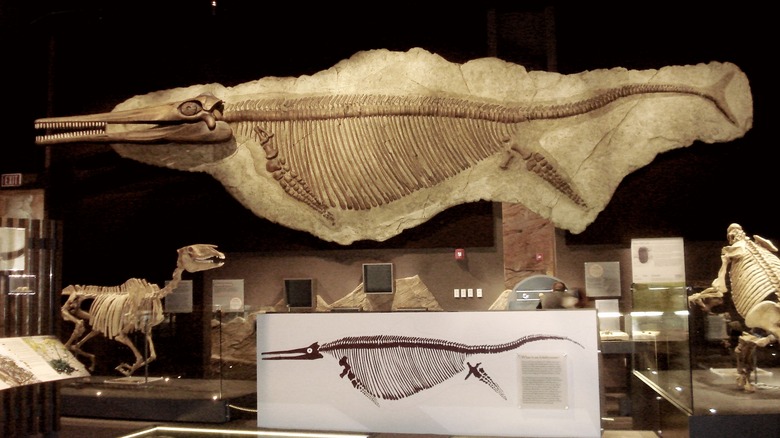

Nevada sea graveyard

Some fossil sites hold more than one specimen in their rocks. One such site gave its name to a preserve, the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. There, multiple skeletons of Shonisaurus, Triassic marine reptiles that somewhat resemble modern-day dolphins, have been found together in one of the park's quarries. The first collection of Shonisaurus at the site was found in the 1950s, and later research in 2014 found repeat gatherings at the same location spanning thousands of years.

Since the first mass find, paleontologists have wondered why so many Shonisaurus died together. Adding to the mystery was the seeming absence of any juvenile animals; all the known fossils were adults, and Shonisaurus was the only species found in the area. Theories have ranged from toxic algae blooms to the reptiles becoming stranded on land en masse. What is now Berlin-Ichthyosaur was then a shallow area of the ocean, and the Shonisaurus could have ended up beached like modern whales.

A study published in Current Biology in 2022 (via The New York Times) examined the rocks the fossils were found in and seemed to rule both causes out. Looking through the bones, the research team found the remains of embryos and newborn Shonisaurus. Based on this, the team suggested the spot was a birthing site. But while this study seemed to explain why the Shonisaurus were there en masse, it still doesn't explain why multiple gatherings died together over millennia.

[Featured image by Kenneth Carpenter via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

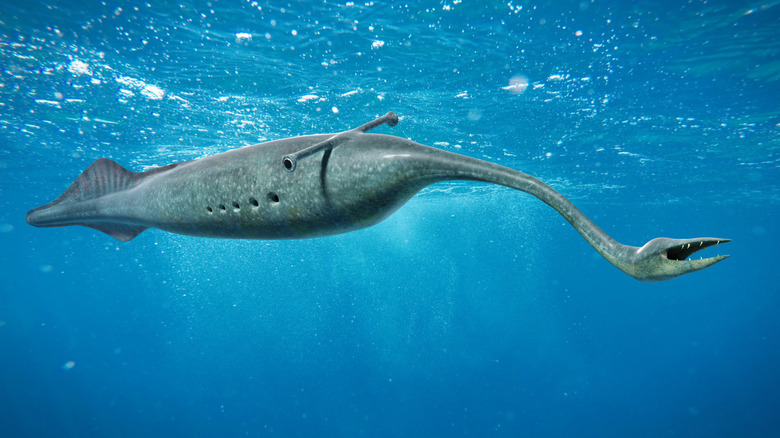

Typhloesus

Its formal name is Typhloesus, but this football-shaped animal has picked up a more catchy nickname: the alien goldfish. Typhloesus lived 330 million years ago in the waters that covered what is now Montana. It had a mouth but no anus, no backbone, no shell, and only one fin, on its tail. The first fossils of Typhloesus were found in the 1960s, alongside other organisms that have since been definitely placed in the tree of life. But the alien goldfish has eluded a firm classification.

Part of the problem in classifying Typhloesus is that other fossils found with specimens have been confused as part of the animal itself. Teeth once believed to be from Typhloesus have since been demonstrated to be from its food. And elements of Typhloesus's own body have been misidentified. A 2022 study concluded that impressions thought to be muscle were actually teeth surrounding a tonguelike organ called a radula.

This finding led the research team behind the study to classify Typhloesus as a mollusk (per Biology Letters). The paper was well-received by peers. But mollusks aren't the only creatures to have radula. And even if that is where Typhloesus belongs in the animal kingdom, it would still be a weird outlier in the gastropod family.

[Featured image by Ghedoghedo via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

The origin of bats

Bats have an unearned sinister reputation. They're handy pollinators and good at pest control. But they are nocturnal animals, often unseen by humans, and that can attract an air of fear and mystery. For paleontologists, bats are mysterious for another reason: They don't know where they came from.

The oldest bat fossils date to around 50 million years ago. Extinct bat species have been uncovered in the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Australia. These fossils have helped scientists track the evolution of bats over time and observe how they developed echolocation and lost the claws on their wings. But every bat fossil known is unmistakably a fully formed bat. The fossils that would represent their immediate predecessor species have never been found.

Bats aren't the only species for which the fossil record has long hidden their ancestry. Whales, birds, and turtles all seemed to turn up without explanation. But fossil discoveries in the 1990s and early 2000s filled in the evolutionary gaps for all three families. Many bats live in forests, which rarely provide ideal conditions for fossilization; if bat ancestors lived in the same environments, that might explain the gap in the fossil record. Professor Emily Brown told the Smithsonian that the hunt for bat ancestors would best be conducted at sites that were once lake beds around the time the dinosaurs went extinct. There, stray animals might have been trapped in mud and been properly preserved.

The Francevillian biota

In 2010, geologist Abderrazak El Albani and his team came upon a large collection of fossils in Gabon. To many, they wouldn't stand out except as strange squiggles or circles within rocks. But those squiggles and circles represent the oldest-known multicellular life forms large enough to see with the naked eye. They are more than 2 billion years old, far older than previous estimates for the development of such life.

Over 400 fossils make up the collection known as the Francevillian biota. They would have evolved during the Great Oxygenation Event that transformed Earth's oceans and atmosphere. Colonial life forms, the biota would have lived in the shallow parts of the ocean. As oxygen levels declined, these relatively large organisms died out, and macroscopic life wouldn't come into full flower until the Cambrian period.

The time period in which the Francevillian biota lived is known as the Proterozoic era, meaning "before animals." According to Scientific American, that is an appropriate descriptor for the fossils too. Just what they are is still unknown, but given their age, it's plausible that they aren't animals or plants as we know them.

[Featured image by El Albani A, Bengtson S, Canfield DE, Riboulleau A, Rollion Bard C, et al. via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 3.0]