The Untold Story Of The Bunker Twins

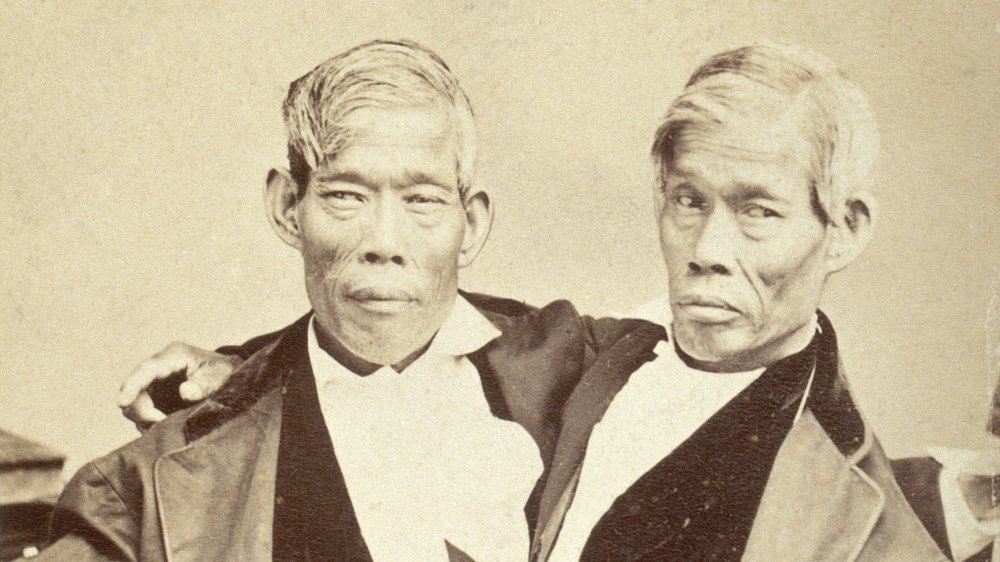

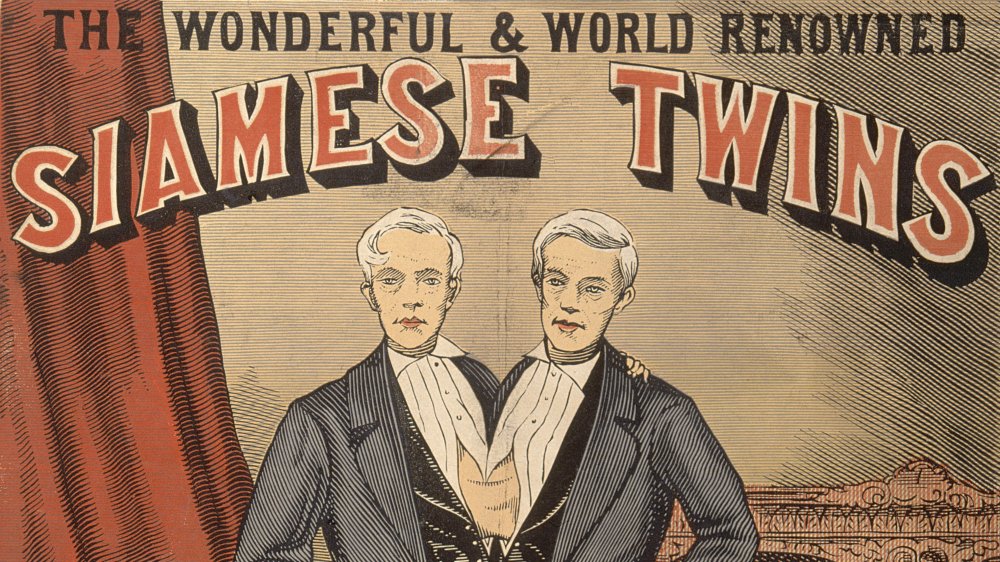

The Bunker twins are likely the most famous conjoined twins in history. At the height of their fame, they toured Canada, the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. Due to the fame and prominence the Bunker twins achieved in their lifetime, they ended up being the first pair of conjoined twins whose condition was documented in detail.

Despite being exploited during their adolescence, the Bunker twins were able to break free and make a name for themselves as an independent act. They were so financially successful that at the height of their career, their worth was equivalent to over $1 million today.

Although the twins never made it back to their home in Thailand, they became naturalized American citizens and made a home for themselves in North Carolina. Marrying a pair of sisters, they had a combined total of 21 children. And now, more than a century later, their 1,500 descendants reunite every year at Mount Airy. This is the untold story of the Bunker twins.

The Bunker twins' early life in Thailand

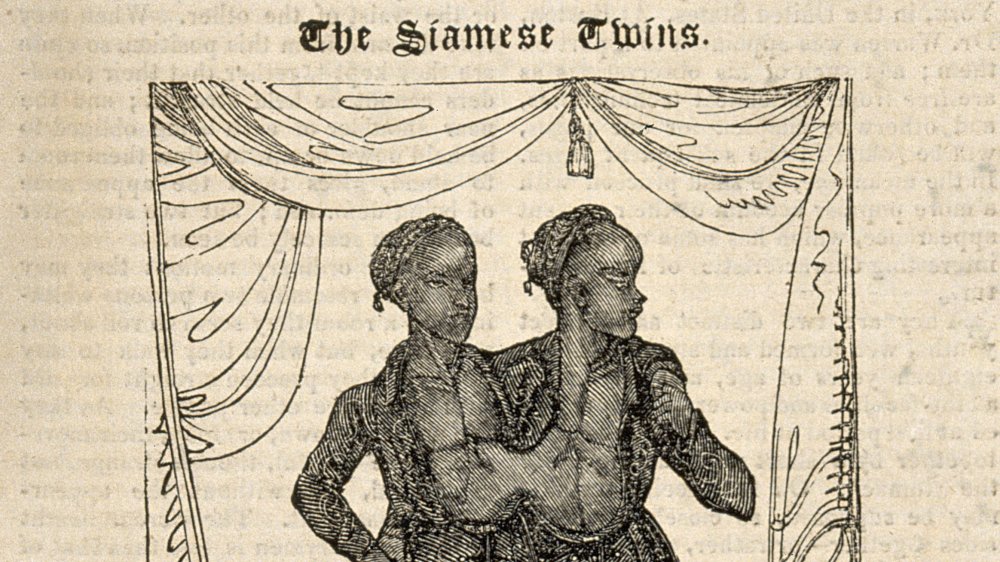

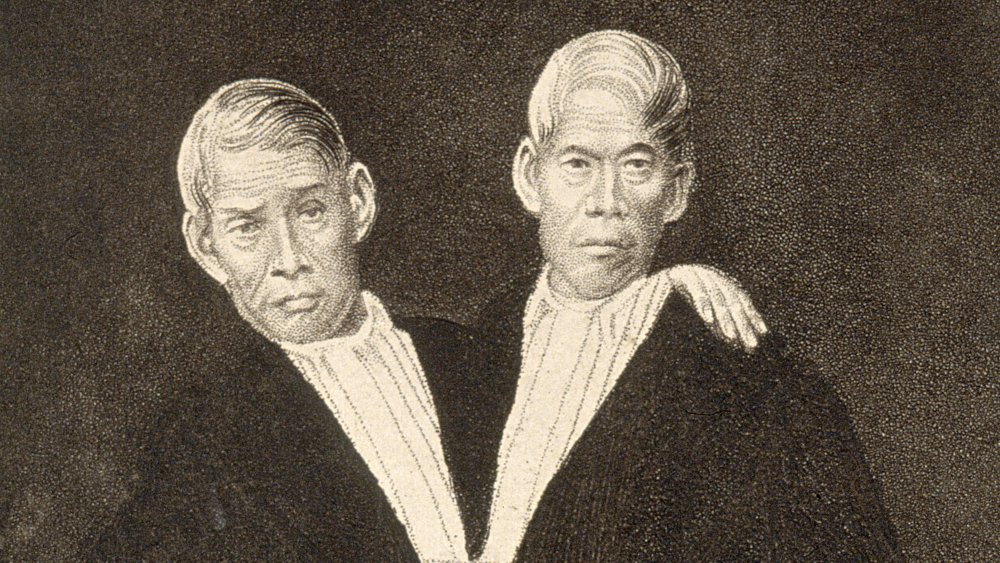

In Meklong, Siam, now known as Thailand, Chang and Eng Bunker were born on May 11th, 1811, to Ti-eye and Nok and were connected by a small piece of cartilage at the breastbone. Although journalists would later dub them "Siamese twins," their father was Chinese and their mother was half-Chinese and half-Siamese. In comparison, locals in Meklong referred to the boys as the "Chinese twins."

News of the twins' birth even reached King Rama II, and as "a dabbler in the interpretation of symbols and signs," he considered the twins a bad omen and put out a death warrant for the them. But something else soon caught his attention, and King Rama II quickly forgot about the "bad omen" in the fishing village.

According to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, at birth, the brothers were face-to-face due to the connecting cartilage. But their mother encouraged them to do exercises while they were young, and soon the tissue had stretched enough — from four inches to five and a half – so that they could walk side by side. Growing up, the boys learned everything in coordination, from walking and swimming to rowing and fishing.

The Bunker twins meet Robert Hunter

In 1819, a cholera epidemic decimated their village, resulting in the deaths of five out of the nine siblings, along with their father, Ti-eye. The 8-year-old twins were soon helping their mother earn money, working in cocoa bean oil manufacturing and raising ducks for their eggs. But the family was financially insecure.

Robert Hunter, a trader from Scotland, was visiting Siam in 1824 when he stumbled across the twins taking a dip in the river after a monsoon. Hunter knew he'd stumbled upon a potential gold mine, and after asking the boys about themselves, he put his plan into motion. According to Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History, by Yunte Huang, Hunter visited the twins repeatedly, "like the suitor returning again and again to serenade the girl he had first sighted at the bend of a country road." Soon he was suggesting taking the twins to America and Europe on an exhibition tour.

Hunter soon wooed the twins by piquing their curiosity about the world. He also offered their mother, Nok, $3,000, along with the promise that the twins would be brought home after the tour. However, Hunter only ended up paying Nok $500, and the twins would never return to Siam.

Hunter also had to convince King Rama II to allow him to take the twins. And although King Rama II initially refused, after Hunter enlisted the assistance of Capt. Abel Coffin, King Rama II acquiesced.

The solo show of the Bunker twins

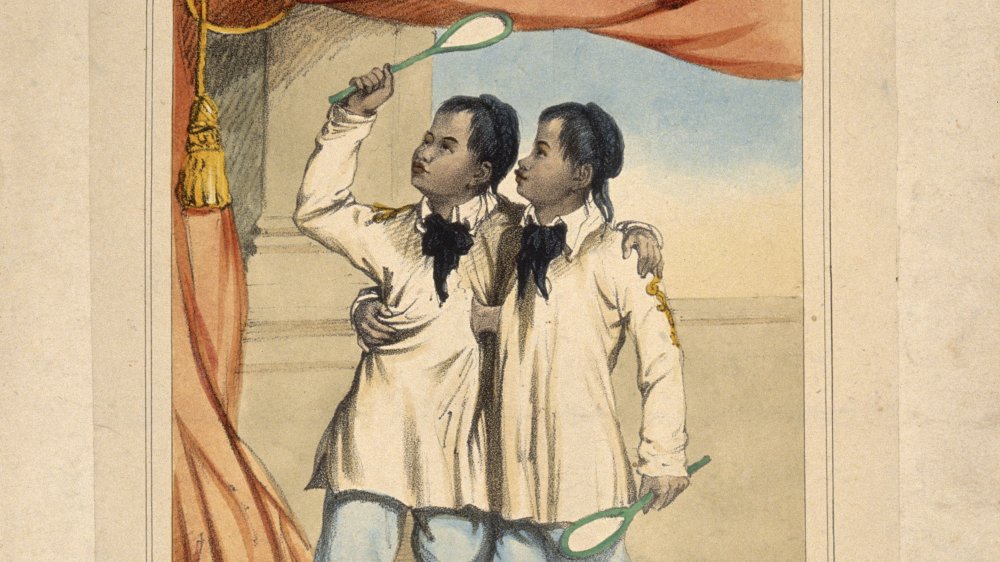

In 1829, the Bunker twins arrived in the United States. The twins spent the 138-day journey to Boston, Mass., learning English. By the time they landed, they were able "to carry on simple conversations in broken English, as well as to do a limited amount of reading."

According to NPR, they performed as a solo show rather than linking up with a larger carnival. But having been tricked into signing a contract with Robert Hunter and Abel Coffin, on April Fools' Day no less, they saw little of what money they earned. And when traveling, the twins were forced to ride in steerage while their owners sat in luxury cabins.

Despite their exploitation, the twins tried to maintain their good humor as they performed their repertoire of somersaults and backflips. Once, upon noticing an audience member who only had one eye, the twins refunded him half of the admission price. A man without legs was given a full refund and a cigar, so the twins could "atone for the fact that they had four arms and legs between them."

When a priest showed up to test the boys, asking if they knew where they were going to go when they died, the Bunker twins pointed their fingers upwards and said, "Yes, yes, up dere." When the priest then asked if they knew where he was going to go when he died, they replied "Yes, yes, down dere," pointing their fingers to the ground.

The Bunker twins' medical examinations

Before long, doctors were brought forth to examine and legitimize the twins in the eyes of the public. The first man to put his "stamp of approval" on the Bunker twins was Dr. John Collins Warren, a leading surgeon in New England and founding editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal.

Robert Hunter and Abel Coffin invited Warren to examine the boys, and Warren was particularly interested in the connective tissue between the twins. He did several experiments in order to elicit pain in the twins, including pricking them repeatedly in order to discern at what point the sensation ceased being mutual.

According to The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Dr. Joseph Skey also performed experiments on the twins while they were in Boston, including one that involved entering the twins' room at night and waking them up by touching just one of them.

Different physicians also examined the twins in London, England, when they traveled there in October 1829. Wherever they traveled, the twins attracted the attention of many different kinds of doctors. Physicians repeatedly verified that the twins were conjoined or sought to verify what the twins shared.

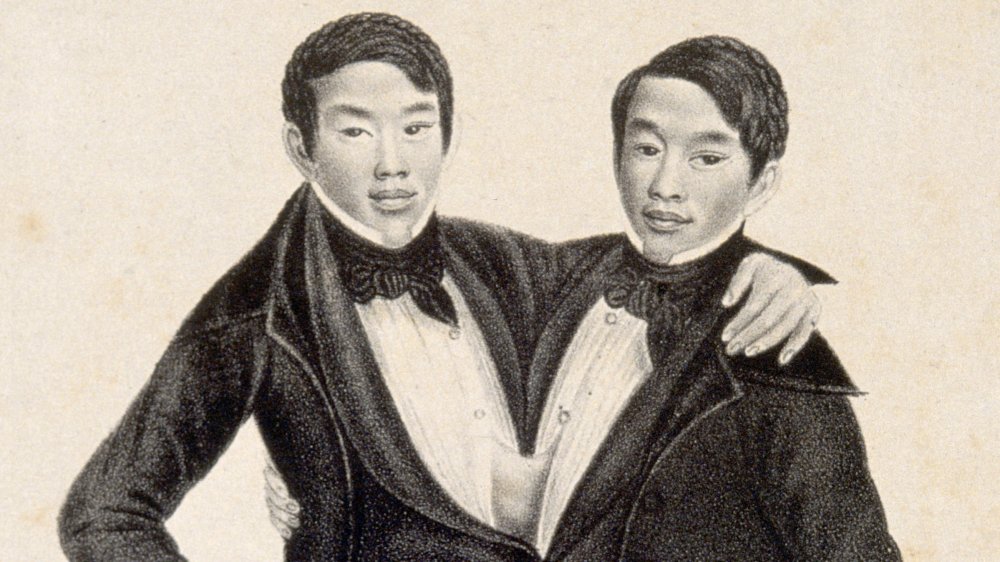

The Bunker twins break away from Coffin

The Bunker twins repeatedly tried to break free from Abel Coffin and finally succeeded in breaking their contract in 1832 when they were 21 years old. By then, Robert Hunter had already sold his share to Coffin, so Coffin was the only one the twins had to deal with.

According to NPR, the twins had repeatedly tried breaking free, but they weren't successful until Coffin was traveling on business overseas. Seizing this opportunity, the Bunker twins wrote a letter to Susan Coffin, his wife, writing that now that they were 21, they were going to go off on their own since Coffin had promised them their freedom on their 21st birthday. When she replied that the boys were ungrateful, they responded by pointing out all the money earned by the twins that the Coffins had been pocketing.

After some back and forth, the Bunker twins wrote one final letter to the Coffins, listing their grievances and describing the mistreatment by the Coffins, ending their letter with the line, "we are on our own." Having broken out of the binds of the Coffins, the Bunker twins soon hired Charles Harris as a manager, "who will work for them, not the other way around," and they continued touring until 1839.

What it means to be a U.S. citizen for the Bunker twins

After spending the 1830s touring independently, the Bunker twins purchased 150 acres in Wilkesboro, N.C., in which to settle down. During their nine years touring independently, the Bunker twins earned $60,000 by the time they retired, equivalent to roughly $1.5 million today.

According to The Lives of Chang & Eng: Siam's Twins in Nineteenth-century America, by Joseph Andrew Orser, their former manager Charles Harris was also especially helpful in opening many doors for them, in the county as well as the nation. In October 1839, the three of them petitioned for and were granted United States citizenship. Chang and Eng didn't actually adopt the last name "Bunker" until they became naturalized citizens. Naturalized citizens needed a last name, so the twins chose the last name of a friend from New York.

And although only "free white persons" were allowed naturalization according to the 1790 congressional act, before anti-Asian sentiments reached their peak later in the late 19th century, a handful of Asian immigrants were naturalized. Because "Asiatic" or "Chinese" weren't official legal categories at the time, the Bunker twins were counted as "free white persons" because they "were not black."

And by using their wealth, celebrity, and connections, the Bunker twins secured a place in American society. Even after "Chinese" became a possible category in 1870, the census continued to list them as "white."

The Bunker twins' marriage to the Yates sisters

Charles Harris also introduced the Bunker twins to Sarah and Adelaid Yates, whom they soon began courting. According to Born Together: The Story of Conjoined Twins, by Michael L. Cox, the twins were welcomed at the Yates household and made many visits. But while Chang was deeply in love with Adelaide, Eng didn't feel much for her sister Sarah but agreed to the double marriage in order to make things easier.

According to The Lives of Chang and Eng, by Joseph Andrew Orser, although historians later wrote that the twins' engagement was met with violent reactions, "none of the twins' associates spoke of mob violence or unrest in their letters that mentioned the wedding." Stories of violence came roughly a century after the wedding itself, with little evidence from newspaper accounts.

The press, however, hardly missed any opportunity to belittle the Bunker twins and their wives. The Louisville Journal wrote, "Ought not the wives of the Siamese twins be indicted for marrying a quadruped?" Abolitionist papers also added to the rebukes. The Emancipator and Free American printed the twins' wedding notice in a column called "Southern Scenes," which typically published stories of murder or robberies. The Liberator claimed that only a priest who was corrupted by the advocacy of slavery could allow for "so beastial a union as this."

But the Bunker twins stayed with the sisters for the rest of their lives, and together, the two couples had a combined total of 21 children.

Slaves of their own

Despite having been treated inhumanely in their youth, the Bunker twins grew up to participate in the act of slavery. According to NPR, the first enslaved person under Bunker control was Grace Gates, who was given to them as a wedding present from their father-in-law.

But within two years, the twins purchased three more enslaved people. Considering that the people they purchased were actually children, aged 7, 5, and 3, it's unlikely that the children were doing a great deal of farming on the land. Instead, children were often purchased because they were less likely to run away and in order to sell them off when they were older.

By 1850, the Bunker twins owned at least 18 enslaved people, most of whom were under 8 years of age. The twins would rarely keep an enslaved man past the age of 25, but enslaved females were kept for the children that they would have, who then became property of their masters.

There are many conflicting accounts regarding the Bunker twins' treatment of the enslaved people on their property. There were stories in the family about the Bunker twins' sons playing with "half-sisters and half-brothers who were enslaved."

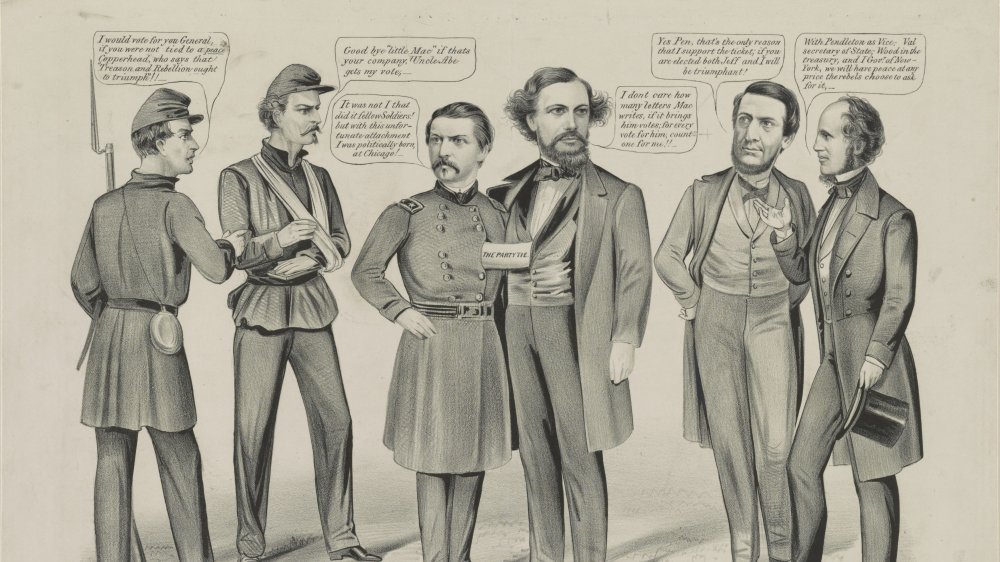

A metaphor for the Civil War

For many in the United States, the Bunker twins were used as a metaphor for unity together with difference, a metaphor that was extended to rationalized American's own national unity and difference after the Civil War.

In 1869, Mark Twain wrote the satirical essay, "The Personal Habits of Siamese Twins," in which the duality of the U.S. is depicted by the twins fighting on opposite sides in the war. After the war, they took each other as prisoners, and in the end, a general army court determined that they were both captor and captive and exchanged them with each other.

According to "Representations of Conjoined Twins," by Claire Marita Fletcher, Twain used the Bunkers twins to underline the potential for collaboration and success, "despite the potential disunity of their situation," speaking to a nation trying to rebuild itself after a bloody civil war. Author Cynthia Wu also wrote how Twain temporarily erased the racial differences of the twins by making them "a symbol of national pride."

But even for Twain, the Bunker twins were nothing more than symbols, "no more than objects of satire." And according to The Lives of Chang and Eng, by Joseph Andrew Orser, the union that the Bunker twins symbolized wasn't a union that was agreeable to many.

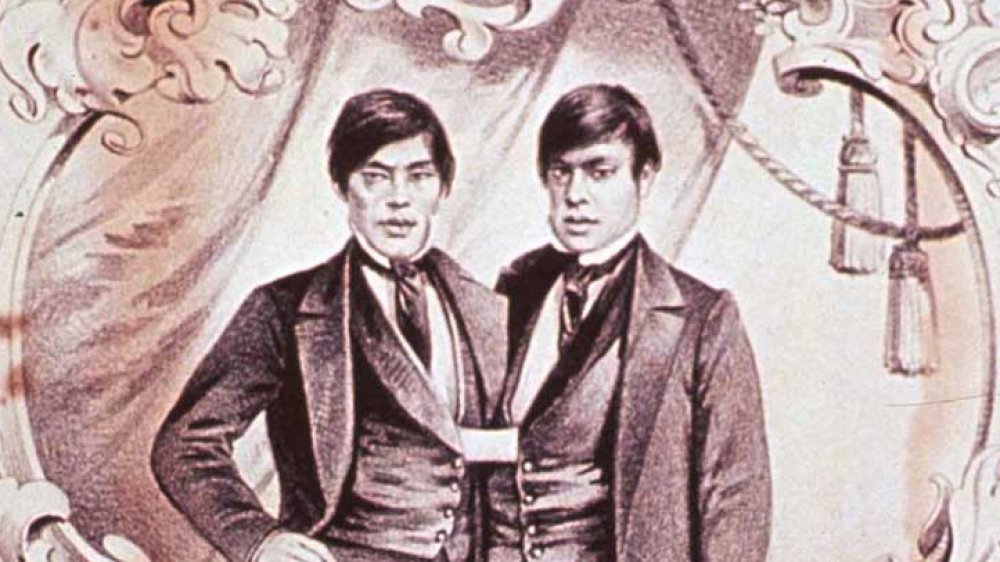

The Bunker twins return to public exhibitions

Although the Bunker twins hadn't completely ceased their touring when they settled in North Carolina, after the Civil War ended and the people they had enslaved were freed, they resumed touring and public exhibitions in order to make money again.

The Bunker twins had invested a great deal of money into the Confederacy, and after the war they lost most of their fortune. According to Our State, after the Civil War, the combined savings of the Bunker twins was barely over $2,000.

At the age of 54, the twins resumed touring, but their time together was less than harmonious. Eng would stay up all night while Chang wanted to sleep, and Chang started drinking more and fell into a depression.

During this time, the twins also sought the opinions of several doctors regarding their separation, fearing the moment when one of them might die. But no one agreed to the operation. One night, Chang threatened to sever their connection with a knife during a drunken rage. They went to Dr. Joseph Hollingsworths afterwards, once more demanding a separation, and the doctor told them instead to cool their tempers.

Chang suffers a debilitating stroke

In 1870, Chang suffered a stroke while the Bunker twins were on their way back from their final tour, leaving him paralyzed on one side. According to Atlas Obscura, in order to help his brother move his legs, Eng was forced to prop Chang's legs with straps and crutches "like a puppeteer."

Pleading with doctors to separate them, Dr. Joseph Hollingsworths finally agreed that in the event of one's death, the Bunker twins would be separated. But tragically, Hollingsworths didn't end up making it in time before Eng also passed.

On Jan. 17, 1874, Chang died in his sleep, and his brother Eng passed several hours later. It was an "unthinkable few hours," while an autopsy concluded that Chang had died from a cerebral clot, "Eng had actually died of fright." However, this was a sensationalized conclusion, and since Chang and Eng shared an artery and a "quite distinct extra hepatic tract," it's likely that Eng's cause of death was blood loss.

A final examination of the Bunker twins

Immediately after their death, doctors were quick to claim their bodies, without providing any compensation to the families. However, it's possible that the widows weren't doing so poorly on their own. According to Beyond the Body Proper, edited by Margaret M. Lock and Judith Farquhar, the widows kept the dead bodies of the Bunker twins in a cool cellar and allowed people "a glance" for 25 cents for almost two weeks. But once a physician from Philadelphia arrived to take the remains to be studied "for science and humanity," the Bunker twins were shipped off to Pennsylvania.

According to Atlas Obscura, their bodies were sent to be photographed, dissected, and studied at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. During the autopsy, doctors discovered that it was unlikely that the twins would've survived a separation, due to the fact that a part of their livers were connected. However, the liver appeared to be the only organ that the brothers shared.

A death cast was made of the Bunker twins' bodies, positioning the brothers as facing one another, and along with their liver, was made a permanent exhibition at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.