What Really Happened With The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Disaster

As of 2020, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is still considered the worst oil spill in the history of the United States. Located more than 5,000 feet below the water's surface, the well leaked for 87 days until it was capped, resulting in over 3 million barrels of oil pouring into the Gulf of Mexico.

After a bubble of methane triggered an explosion in the rig, numerous errors led to a failure of the safety equipment that would've prevented the successive oil spill. Later, it was also revealed that cost-cutting, time-saving methods used by Halliburton made a blow-out all but inevitable.

Despite unprecedented government fines, BP reinvented themselves and went on to invest further in numerous oil and natural gas projects. Simultaneously, more than ten years later, local wildlife and communities of people continue to suffer from the effects of the oil spill. This is the story of what really happened with the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster.

What was Deepwater Horizon

Built in 2000, Deepwater Horizon was an oil rig that operated in the Gulf of Mexico for approximately ten years before the BP oil spill. Built in South Korea by Hyundai Heavy Industries, Deepwater Horizon was put into service in 2001.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the rig was primarily owned and operated by Transocean, an offshore-oil-drilling company, and through them it was leased to British Petroleum LLC, or BP, under long-term contract until September 2013. Costing approximately $365 million to build, the Deepwater Horizon was leased to BP at a rate of $502,000 per day.

Although the Deepwater Horizon had a rated drilling depth capacity of 30,000 feet, according to Transocean, in early 2010 Deepwater Horizon drilled to a depth of 35,000 feet. And it's not unlikely that the unprecedented depths contributed to the severity of the explosion. Every 100 feet of added depth increases the likelihood of a serious accident, such as fire or explosion, by 8.5%.

The explosion of Deepwater Horizon

The oil well that the Deepwater Horizon was positioned over had been temporarily sealed with a concrete core, and while the Deepwater Horizon was still positioned above the Macondo well, a surge of natural gas blasted through the concrete on April 20, 2010. Traveling up Deepwater Horizon's rig riser, the natural gas ignited on the platform, resulting in an explosion that killed 11 workers, injured 17 others, and capsized the rig. The rig sank two days later on April 22, at which point it ruptured the marine riser. A mile-long pipe, the riser injected drilling mud in order to counteract the pressure from the natural gas and oil. Without the resisting pressure, oil subsequently began to pour into the Gulf of Mexico from the damaged wellhead pipe.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, although the blowout preventer should've been automatically triggered when the explosions occurred, automatic functions failed due to improper maintenance. Subsequent attempts to "operate the blowout preventer with remotely operated vehicles on the ocean floor also failed."

Investigations later revealed that not only did Halliburton know that the cement mixture they used for the concrete core was flawed but that BP had experienced and covered-up "a nearly identical blow-out" two years prior on an oil rig in the Caspian Sea. In the end, both concrete cores installed by Halliburton used a "quick-dry" method that led to the cement being unable to withstand intense pressure.

Attempts to cap the Macondo well

Engineers tried repeatedly to stop the flow but to little avail. According to The Guardian, it took ten different attempts to cap the Macondo well. One attempt involved putting a dome over one of the leaks, an approach known in the industry as a "top hat." Another approach, known as a "junk shot," involved "firing shredded tyres and golf balls into the blowout preventer in the hope of clogging it."

A "capping stack," a cap on top of the blowout preventer, installed on July 10 was ultimately successful. This gave the engineers enough time to pour cement and mud into the well in order to reduce pressure and staunch the oil on July 15, 2010, after 87 days of continuous flow.

During this time, two rigs were also simultaneously drilling two relief wells to intercept the flow of the Macondo well. It was through these relief wells that cement was poured in, permanently sealing the Macondo well on Sept. 19, 2010.

Months of oil and natural gas debris

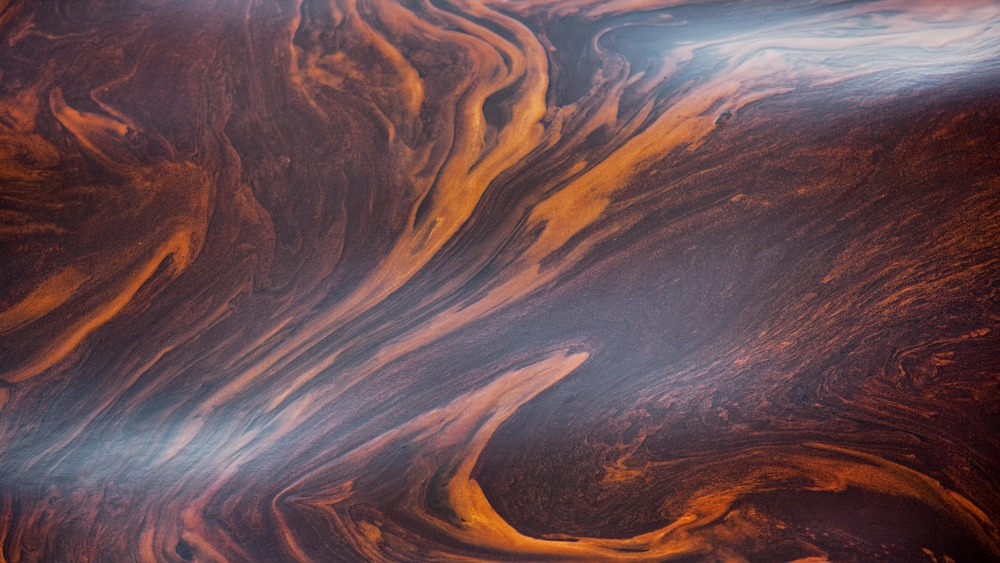

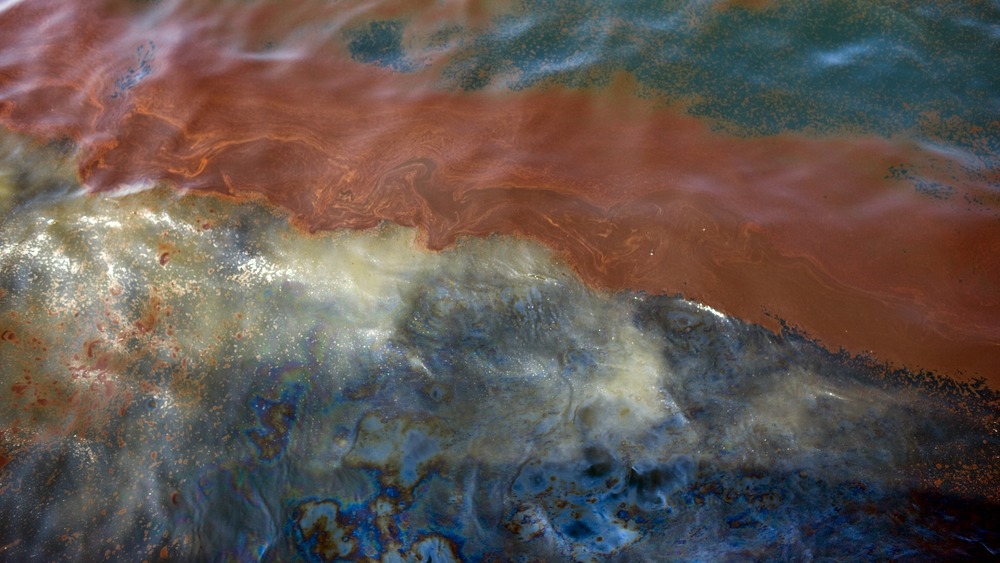

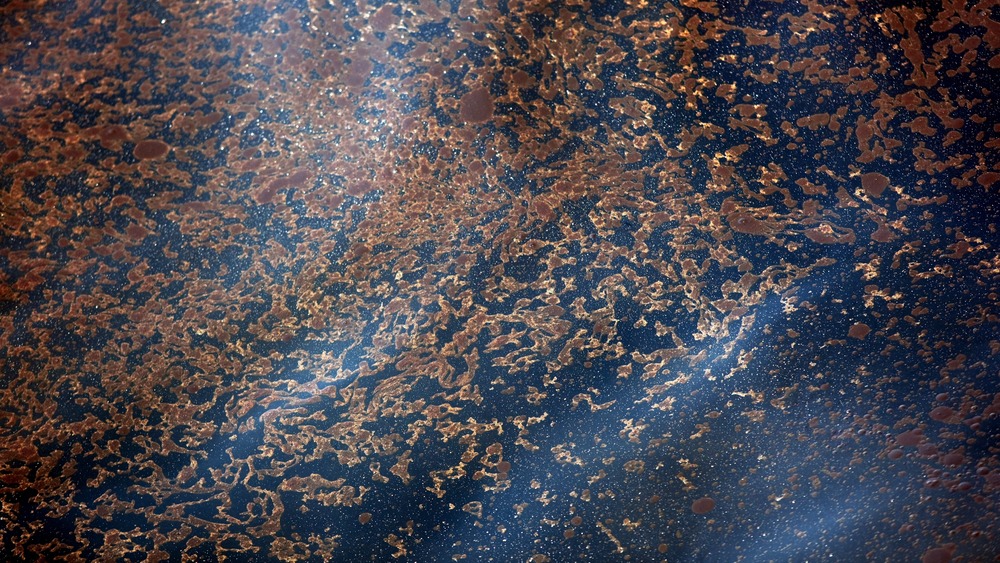

Within one month, more than 3 million gallons of crude oil had poured into the Gulf of Mexico. Five months after the explosion, the well was permanently sealed on Sept. 19, 2010. But by that point, upwards of 200 million gallons of crude oil had been released into the gulf, covering over 15,300 square miles at its maximum extent and affecting over 16,000 miles of coastline, stretching from Texas to Florida.

While some of the oil floated to the surface and formed oil slicks, some oil remained suspended in the water, creating oil plumes. According to PBS, this was the result of several factors, including the depth of the leak as well as the fact that "BP sprayed 1.8 million gallons of dispersants at its source." The use of dispersant also had an "unforeseen consequence" of increasing the spread of the oil by 49%. It's also estimated that 20% of the spilled oil ended up in or on the seafloor. Unfortunately, all of this makes it difficult to determine exactly how much oil spilled into the gulf.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it's also estimated that at least "7.7 billion standard cubic feet of natural gas was also released from the well."

Cleaning up with controlled burns

In an attempt to "clean up" the oil, roughly 5% was burned off between April 28 and July 19, through over 400 controlled, or "in situ" burns. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, fire teams were directed to heavily concentrated areas of oil, and after containing "a sufficient amount of oil using fire boom ... [they] then ignited the oil." Over 11,000 barrels a day were burned, but the most occurred on June 18, when 16 different burns consumed between 50,000 and 70,000 barrels. While some burns were short in their duration, others lasted several hours.

Controlled burns were limited to areas with burnable amounts of surface oil, and despite covering a comparatively small area, large amounts of aerosolized black carbon soot were released into the atmosphere. According to the Yale School of the Environment, between 1.4 million and 4.6 million pounds of black carbon was released into the atmosphere over the nine week period of controlled burns.

Other Deepwater Horizon cleanup efforts

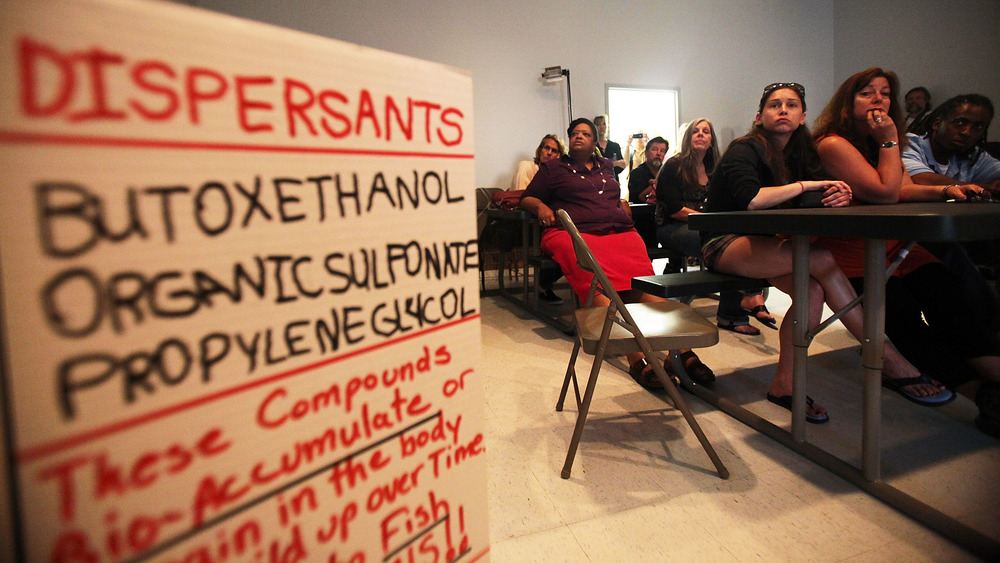

There were various cleanup efforts associated with the BP oil spill. One of the methods often used for oil spills are dispersants, which are chemicals that break the oil down so that it's more easily dissolved by the water. However, in addition to the unforeseen effect of contributing to oil plumes, the combination of oil and dispersant may be almost 50 times more toxic to microscopic wildlife than oil itself.

In addition to the nearly 2 million gallons of dispersant, there were numerous other cleanup efforts for the oil spill. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, mechanical surface skimmers were used to remove oil from the surface of the water, covering both nearshore and offshore waters. Between April and mid-July, efforts increased from 26 skimming vessels to 593 different vessels.

As attempts to stem the flow of oil from the well failed, water from the Mississippi River was released to keep the oil from moving into marshes and shoreline areas. However, this was used for such an extended period of time that the salinization levels of the Louisiana coastal areas were greatly affected.

And unfortunately, according to The Guardian, it's highly unlikely that the cleanup efforts will ever remove every bit of oil. And with oil buried beneath the sand, it ends up remobilizing during every hurricane season.

Downplaying the severity of the Deepwater Horizon leak

Not only was BP aware of the potential failure of its concrete core before it occurred, but after the explosion, they repeatedly downplayed the severity of the leak. According to The Guardian, an internal memo revealed that BP's assessment of the leak was roughly 20 times larger than the estimate that it gave the public. While BP initially said that the leak was gushing 1,000 barrels a day, their internal memo projected a potential 100,000 barrels a day. At its peak, the well was leaking between 60,000 to 80,000 barrels a day.

In addition to lying to the public, BP lied to regulators about their preparation for a spill of this size. And in the end, "everything was guesswork. No one knows how much oil is still down there."

After the oil spill, BP also poured millions of dollars into a publicity campaign to repair their image. According to Campaign, BP spent over $90 million on advertising between April and July, "directed at local and national newspapers, magazines, [and] television."

Whose fault was the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

In the end, a New Orleans judge ruled that BP was most at fault. According to Time Magazine, in 2014, U.S. District Judge Carl Barbier "attributed 67% of the fault to BP, 30% to Transocean, which owned the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, and 3% to Halliburton, the cement contractor." However, BP wasn't alone in their reckless decision making, and the oil spill happened because of years of cutting corners

Although Barbier described their conduct as negligent and reckless, BP was the only one who faced any fines. According to The Verge, the United States government fined BP a record $20.8 billion. But by 2018, BP had paid over $65 billion as various claims added up.

Transocean was also fined $1.4 billion in 2013, despite giving its top executives bonuses in April 2011 for the "best year in safety performance in our company's history."

The oil industry as a whole also tried to distance themselves from BP and "make the disaster appear to be a one-off event." Since 1969, over 40 oil spills have occurred affecting U.S. waters, and even small spills can cause major harm. And spills don't only occur in oil wells. Oil pipelines across the U.S. have spilled roughly 3 million gallons of oil per year since 1986.

BP pays their way out

In 2012, BP pled guilty to "14 criminal counts for its illegal conduct leading to and after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster." This guilty plea also came with a $4 billion fine, but none of the charges resulted in any prison time for anyone. Overall, the counts included felony manslaughter, felony obstruction, and violation of the Clean Water and Migratory Bird Treaty Acts.

However, despite a claimed attempt to hold individuals accountable, manslaughter charges were dropped by 2015. According to The Advocate, the U.S. Justice Department claimed this was because "circumstances surrounding the case have changed since it was originally charged." And according to CBS News, Anthony Badalamenti, a former Halliburton manager, received just one year probation for destroying evidence in the aftermath of the spill.

By 2016, the Justice Department's probe into "four, mostly lower-level BP employees" had come to a close. Rig supervisor Robert Kaluza was acquitted of violating the Clean Water Act. Rig supervisor Donald Vidrine pled guilty in exchange for ten months probation. Former BP Vice President David Rainey was acquitted of obstruction, and engineer Karl Mix received six months probation after pleading guilty to damaging a computer.

Other than some hours of community service and monetary fines, BP, Transocean, and Halliburtan suffered little-to-no repercussions. According to Antonia Juhasz, author of Black Tide, "What is really shocking is that BP has recovered so well."

The health consequences of the BP oil spill

The Deepwater Horizon disaster had short and long-term effects on people's physical and mental health. These health impacts were found in both cleanup workers and people living near the affected shorelines.

According to Frontiers in Public Health, a study assessing the long-term health effects found that those who were involved in the oil spill cleanup suffered from disorders in their heart, lung, blood, and liver function. Symptoms also appeared to persist at least seven years after the exposure to the oil spill. Some oil cleanup workers also assert that BP forbade them from using respirators and didn't inform them about the hazards of Corexit, the dispersant used, resulting in damaged memory and lung capacity.

Out of those living within ten miles of the coast, nearly 20% of adults experienced respiratory problems or skin irritations that they attributed to the spill. And according to the Earth Institute at Columbia University, children living in the area also suffered from physical and mental health problems as a result of the oil spill. Even children with indirect exposure through their parents were found to be much more likely to have physical health problems.

People who've suffered health problems as a result of BP continue to file lawsuits against BP, and residents and workers in the Gulf Coast can continue to find out if they're eligible to join a lawsuit and receive compensation from an existing settlement.

The effect on animals in the gulf

In the first six months after the spill, over 8,000 marine animals and seabirds were found injured or dead. Oil covered the feathers of hundreds of seabirds, rendering them unable to fly, float, or regulate their body temperature. According to the Smithsonian Institute, seabirds that ingested oil suffered from a myriad of health problems ranging from hypothermia to decreased eggshell thickness. Countless eggs were also crushed by workers during the cleanup. In 2014, it was estimated that 800,000 seabirds died as result of the spill, but it's possible that the number is as high as two million.

More than 150,000 sea turtles are also believed to have died because of the spill, and strandings of both sea turtles and dolphins increased in the time after the spill. Deep sea corals also suffered and were found dead and dying up to seven miles away from the Macondo well.

According to the National Wildlife Federation, it could take "decades and decades –- if not hundreds of years" for the coral affected by the Deepwater Horizon disaster to recover. And since coral grows and reproduces so slowly, some of the effects have yet to be seen.

The only animals that seemingly benefited from the oil spill were a select group of bacteria that consume oil, who were able to flourish in the plumes of oil.

The continuing harm of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

Ten years later, many animal and human populations in the area are still struggling against the effects of the BP oil spill. And according to National Geographic, many of the symptoms that are suffered by wildlife communities, like dolphins, are mirrored in the human populations around the Gulf of Mexico — symptoms that include heart issues, lung disease, higher rates of reproductive failure, and death.

More than 100 million gallons of oil is also thought to have landed on the seafloor, and even ten years after the spill, researchers are unsure whether or not the oil is getting "resuspended into the water and affecting cetaceans' food."

Within days of a year-long ban being lifted, BP won 24 oil contracts from the U.S. in 2014. According to The Conversation, as of 2020, there's still no legislation to increase a company's liability for an oil spill, and in 2019, the Trump administration relaxed or completely reversed existing safety reforms.

There was also a complete denial by BP that the oil ever reached Mexico, but ten years after the spill, fishing communities in Mexico continue to feel the impact of decimated fish populations and "have not received a single cent in compensation." In addition to fishing communities being affected around the Gulf of Mexico due to the decreased fish and oyster populations, the oil and chemicals used to disperse the oil killed off the surrounding vegetation, resulting in land erosion, leading to more and more flooding.