The Disturbing History Of Death Photography

You've probably stumbled across an old Victorian picture of a dead person before, whether it's while going through a battered family photo album or just searching for weird things on the internet. These images of corpses, dressed to the nines, surrounded by toys or family members, are extremely disconcerting to modern eyes. Especially when said corpse's own eyes have been propped open and are staring right back at you. Who ever thought this was a good idea? What the heck was wrong with the Victorians?

Well, a lot of things, but death photography wasn't one of them. Taking pictures of loved ones who had passed on became popular almost as soon as rudimentary photography was invented and stayed popular for decades. It was obviously something people at the time not only didn't find weird but were really into.

So why was death photography so important, how exactly was it done, and did it ever really stop? Read on to learn the disturbing history of death photography.

Death photography just continued an old tradition of "mourning portraits"

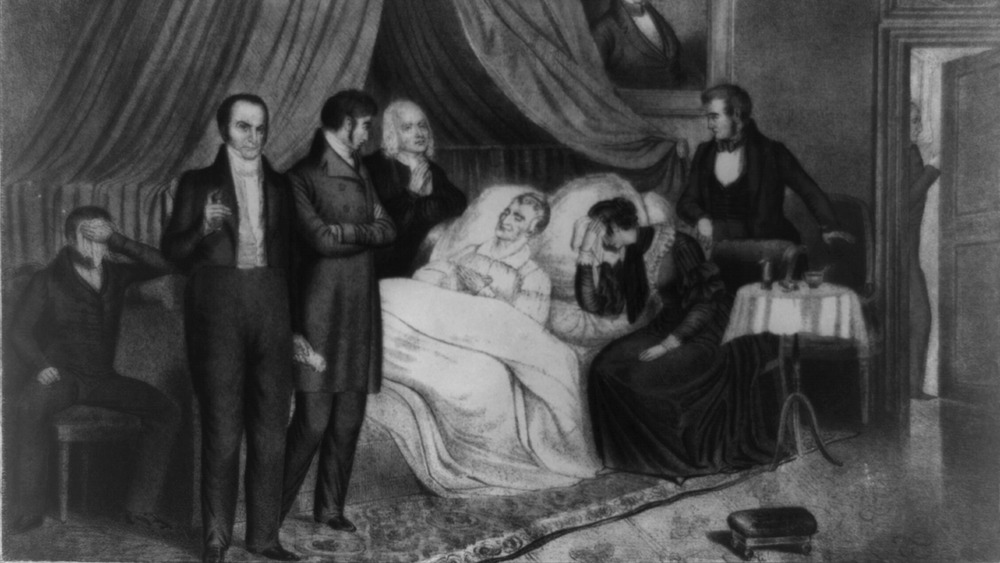

Despite death photography emerging within the first couple years of the invention of the daguerreotype, taking photos of the recently deceased was just a much quicker way of capturing their deathbed moment. While a photo might take a few minutes, before the invention of the camera, someone had to sit in the room long enough to paint a picture of the corpse. These were known as "mourning portraits," and they were incredibly popular.

According to the Guardian, the celebrated Dutch artist Anthony van Dyck was hired by Sir Kenelm Digby to paint his wife, after he found her dead in bed. The family rubbed her cheeks to get some color into them then had Van Dyck paint her "as if asleep." Digby probably cherished the painting forever. You can imagine him looking at it, hoping his wife might yet wake up.

But it wasn't just something artists were hired to do. At the deathbed of a family member, in an intense moment of grief, many turned to their creative outlet. Claude Monet painted his dead wife on her deathbed. Lucian Freud painted his mother. And Gustav Klimt sketched a haunting portrait of his infant son Otto shortly after his death. So really, the only thing cameras did was speed up the process.

A postmortem photograph might be the only memento left of a loved one

Believe it or not, there was a time when everyone didn't have a camera basically attached to their hand, and they didn't take 500 selfies every single day. In fact, when they died, there might not be one single solitary photograph of them at all.

Photography, especially in the beginning, was expensive. It was art, and just like sitting for an oil portrait wasn't something most families could afford, a photographic portrait was another extravagance. But it wasn't as expensive, and if you'd lived back then, it might only have been when your loved one died that you decided it was worth the money to have an exact image of them to cherish forever. As the BBC notes, if you were a parent who had just lost a young child, before you buried them was your last chance to get a picture.

That's why, according to History, rather than being macabre, these images were "taken in love." Dealing with death is difficult at the best of times. But the amazing new invention of photography allowed families to lessen their grief just a little, knowing they would always have a picture of their deceased loved one to look at, carry with them, or proudly frame on the wall.

Dead bodies made great photographs

Taking a look at early photographs, many of them are blurry. This wasn't down to the technology available: Victorian cameras were perfectly capable of taking crisp images. But the technology was slow. Subjects had to sit perfectly still for 20 seconds or more, according to the University of North Carolina. No blinking, no twitching, even breathing made a photograph blurrier. All while sitting or standing straight up, in super uncomfortable clothes, knowing this might be the only photograph you ever have taken. No pressure.

So yes, taking a clear photo of a person was ridiculously hard. An alive person that is. You know what's great about dead people? They don't move. Not even a need to breathe is going to ruin their photos. If you're an early portrait photographer who is trying to perfect the artform and produce gorgeous, clear portraits that will show off your abilities, corpses are ideal clients.

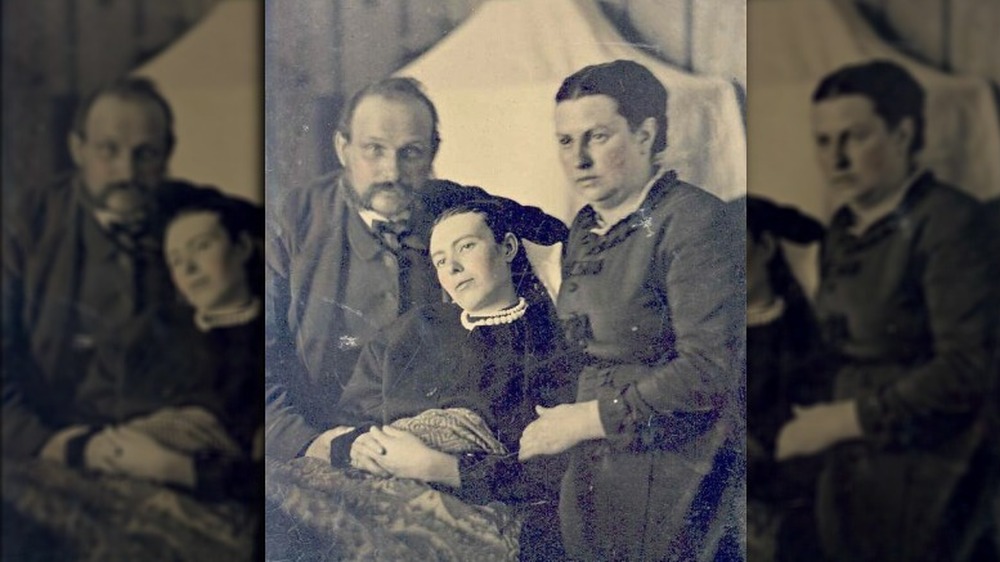

It also makes sense why a family would want a picture of their deceased loved one. Even if they did have one or two photos of them already, the one taken after their death would definitely be sharpest and show their features in the most detail. Family members often posed with the dead body, which was sharpest in focus, surrounded by slightly blurry people.

There were tricks to getting the perfect postmortem photo

While the fact they didn't move made corpses a photographer's best subject, that didn't mean death photography was easy. After all, it is a dead body. Dead bodies start smelling, they don't take direction, and they can't even say "cheese."

Death photography was such a big business, the Order of the Good Death reports that trade journals like the Philadelphia Photographer gave tips to "afford assistance to some photographer of less experience, to whom it might befall the unpleasant duty to take the picture of a corpse." An 1869 edition said to place the corpse near a window, to take advantage of the natural light. (This of course meant actually moving the dead body, which was literally deadweight at that point.)

But even bright sunlight couldn't make a dead body look alive. If that was the photographer's goal, they were going to need to open the corpse's eyes. Fortunately, the January 1871 edition of the Philadelphia Photographer had just the solution for exposing those peepers: "This you can effect handily by using the handle of a teaspoon; put the lower lids down, they will stay; but the upper lids must be pushed far enough up, so that they will stay open to about the natural width, turn the eyeball round to its proper place, and you have the face nearly as natural as life." Death photography may have been an important cultural practice, but it sounds like calling it an "unpleasant duty" was an understatement.

Sometimes the death part of death photography was edited out

Just because a Victorian portrait looks creepy — like something is a bit off — doesn't mean the person in it is dead. There is a prevailing myth that if you can see a stand behind the person in the photo, they are really a corpse, and that's what is holding them up. Susan Marville Cantrell felt strongly enough about this urban legend to create the website Victorian Postmortem Photos: The Myth of the Stand-Alone Corpse. As she points out, dead bodies are heavy and can't support themselves at all. To get one to stand upright would need at least three people to hold the arms and the head, and even then, the person wouldn't look like they were standing at attention. Instead, the stands you see in photos were used on living people, to keep them from swaying during long exposures.

This didn't mean there weren't attempts to make corpses look a bit more lifelike. The BBC found examples where children were propped up in a chair, surrounded by their favorite toys. Or it might be a group photo with various still-alive family members. While tricks like using spoons to hold open a corpse's eyes seem like a lot of effort, some photographers just went old school Photoshop and edited their images. This might mean drawing on some open eyes or adding some pink color to the cheeks. There was only so much they could do and, in most photos, it's super obvious.

Death photography made kicking the bucket look peaceful

Death is rarely pretty. But if you look at Victorian death photography, this reality is completely erased. The photos are actually quite beautiful. And this was absolutely done on purpose.

Not all families asked that their deceased loved ones look like they were still alive, complete with spoons propping open their eyes. One of the most popular styles of death photography, according to the Clara Barton Museum, was making the subject look like they were taking a nice nap. Known as "The Last Sleep," this pose gave comfort to the living in a variety of ways.

One, it made it look like the corpse wasn't really dead and could wake up any time to rejoin them in life. And since zombies weren't a thing yet, that thought wouldn't have been creepy. Two, the restful pose allowed parents in particular to believe that their child had passed on happily into another lovely, peaceful realm. Finally, one historian thinks it probably reassured the living, who might have just seen someone suffer a really horrible death, that actually "the final act of dying is as simple and painless as going to sleep — and practically, we all die daily, without knowing it, when we go to sleep for the night." See? No need to worry about the existentially terrifying reality that you will die. You basically do it every night, and it's fine. Need proof? Here's a picture of a nice, peaceful dead body.

Death was everywhere in Victorian times not just in photos

These days, spending a bunch of money to take a fancy portrait of a dead relative seems crazy. But that's because these days, in the Western world at least, death is hidden away. People ignore its reality as long as possible. But death wouldn't have been as shocking or creepy to Victorians, according to the University of North Carolina. The death rate was much higher and the life expectancy much lower. This meant friends and family would constantly be dropping dead. It was common to lose children or siblings at a young age. Death would have been close by at all times, from childhood onwards.

And when people were dying, they went through it at home, not in a hospital. They died at home, and the funeral was held at home. A house would be full of memories of death, and the occupants would see dead bodies much more often than seen in the modern day. So seeing the image of a dead body wouldn't hold anything like the kind of shock it does today.

Mourning photography was just another element of the death-obsessed Victorian society. Displaying pictures of dead loved ones in a home wouldn't creep out visitors. They would be used to seeing displays made from the deceased's hair, the family wearing full mourning clothes, everything black down to the jewelry, reams of black crepe over every door, and more. Death was just a part of life.

Death photos of celebrities sold like hotcakes

Having a picture of a dead loved one is one thing. After all, you knew them. It makes sense you'd want to look at the image and remember the good times, take solace in how peaceful they look, and remember every detail of their face. But buying a picture of a celebrity on their deathbed? That's harder to defend.

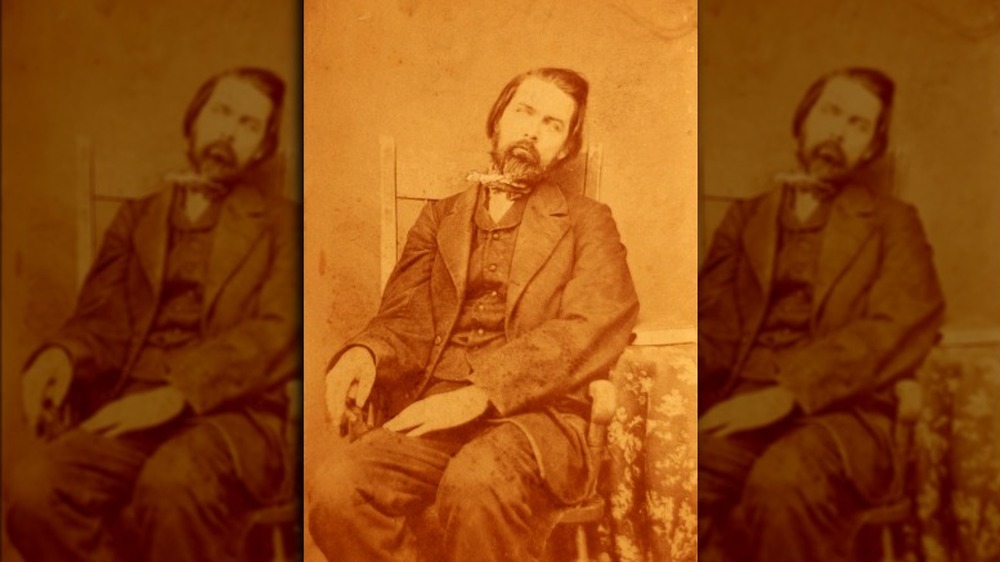

Still, the photography boom saw sales of images of all kinds, so why not throw some death photography into the mix? Victor Hugo, author of Les Misérables, was a massive celebrity in his day, and the image of him taken after he died (pictured) was sold as a card, according to History. But he was far from the only one.

This fascination with the dead bodies of famous people has never really stopped, but by making death more illicit — something not to be seen or talked about — these photos now have a much seedier side to them. Those who are willing to take sneak pictures of celebrities in their caskets can make a quick payday from the sleaziest tabloids, who splash the images across their covers. Assumedly some people then buy those publications, so there's at least a segment of the population that's still fascinated in seeing them. The National Enquirer defended publishing a picture of Whitney Houston in her coffin by saying the image was "beautiful," while a photo of the singer's daughter Bobbi Kristina Brown netted its unscrupulous photographer over $100,000.

The Civil War resulted in a different kind of death photography

Death photography wasn't just limited to the home. Right as photography was becoming more popular, the Civil War broke out. This meant that for essentially the first time in history, accurate images could be taken of generals, moments in battle, and ... the aftermath. Unless war was happening on your doorstep, it had always been a far-off thing. Now, photography showed the casualties of war in vivid detail to every person on both sides of the fighting, and it wasn't pretty.

According to NBC News, the premiere Civil War photographer was Matthew Brady, although he had a large group of assistants, many of whom took some of the famous photos credited to him. A lot of those photos were of piles of dead soldiers or bodies strewn across battlefields. In 1862, the New York Times wrote, "Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it."

These images were first shown in galleries (photography was and is, after all, an artform), and then many of the pictures were reproduced in newspapers or as collectable cards. There is no doubt they were effective. While there is some debate over whether Brady and his team moved bodies to create better images, what they definitely did was remind those on the homefront that death wasn't always as pretty as their photos of seemingly sleeping children made it seem.

Death photography fell out of style, but it never really went away

By the turn of the 20th century, death photography was falling out of fashion due to a confluence of changes in society. A major positive was that infant mortality rates dropped, according to The Order of the Good Death. As medical science was able to make sure most kids made it to adulthood, there was less of a need for postmortem photos of children. But those medical advances also changed how and where people died. When someone, young or old, got sick in the 1900s, they went into a hospital. That meant death and dying was suddenly clinical and behind closed doors, rather than in the comfortable and open realm of the home. Hospital beds didn't lend themselves to peaceful photos so well, and doctors probably didn't want photographers trampling around the place.

But that was the other thing. Photography had become cheaper, simpler, and more popular than ever. You didn't need a professional photographer to take your picture anymore and could afford to do it many times in your life. That meant there wasn't an imperative to capture one last photo, since you probably had dozens of everyone you loved already.

Still, death photography stuck around — it was just a much more private affair. There are innumerable examples of postmortem photos from the 20th and even 21st century (like Pope John Paul II, pictured). But there wasn't the societal craze for sharing them or putting them on display. Instead they became much more personal and intimate. Until the advent of social media and the selfie, that is. Now you can find pictures of bodies in coffins on Instagram, because if you don't share it, did the person even die?