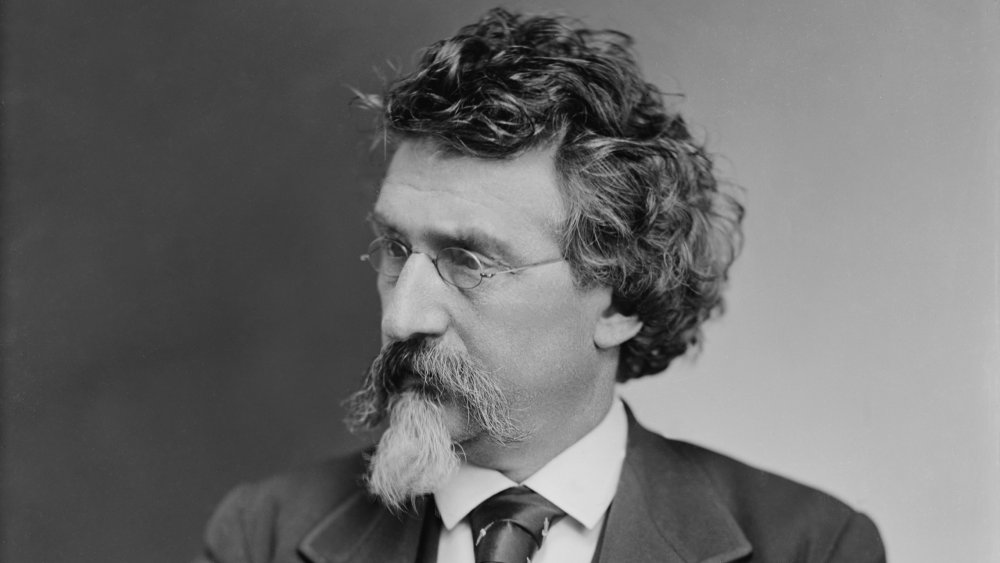

The Untold Truth Of Civil War Photographer Mathew Brady

These days, we take it for granted that we can learn what's happening in our own backyards or even around the world. The 24/7 news cycle, social media, and constant barrages of information keep us informed — sometimes more informed than we want to be.

But for most of history, we had to rely on word of mouth to learn what was going on in the world. Heck, there could be a battle a mile from your house and you might not know about it, to say nothing of a conflict raging on the other side of the globe.

All that changed with the pioneering work of the 19th-century photographer Mathew Brady, who went from taking portraits of the rich and famous to taking death portraits on Civil War battlefields to show people the true cost of the deadly conflict between the states.

Brady's work shaped photojournalism, and war reporting, for the ages. But what do we really know about the man who risked everything to use his art for the greater good?

Who was Mathew Brady?

In the early days of photography, Mathew Brady was an undisputed star. As The Spruce explains, several different ways to capture real-life images for later were developed nearly simultaneously in the mid-to-late 1800s. Brady picked up on daguerrotyping, a method of creating a detailed image on a silver-covered copper plate that was invented in France in the 1830s. According to the Library of Congress, he was one of the first artists to open a daguerrotype studio in the US in 1844, quickly becoming known for his stunning portraits. He expanded to several locations, as Encyclopedia Britannica relates, and made a name for himself as a celebrity photographer.

But Mathew Brady wasn't satisfied with taking snaps in a studio. When the Civil War broke out, he moved to the field and became the most prominent photographer of the Union Army, per the American Battlefield Trust. He documented a series of battles in stark detail, shocking the nation by showing the true bloody costs of battle, as Open Culture details.

Mathew Brady's early life is a mystery

For someone so influential during a key part of American history, we don't know much about Mathew Brady's early life — possibly on purpose. As Mental Floss says, he may have wanted to cover up his humble beginnings or write his own history when he started becoming famous as a photographer. We're not even sure whether he was born on American soil — on his 1863 Civil War draft forms, Brady recorded himself as being born in Ireland, but other records list him as being born to Irish parents in the small town of Johnsburg, New York. Brady himself would go on the record several times to say he was born in the US.

Why would Brady intentionally erase his own past? IrishCentral notes that there was heavy anti-Irish sentiment in the mid-1800s, when Irish immigrants fleeing the famine were accused of stealing work from native-born Americans. Brady may have felt that his childhood in upstate New York made a better story, or would be more appealing to clients, than the truth of having immigrated as a young child. Plus, after his photographic exploits and vehement Union loyalty during the Civil War, Brady may have wanted to polish his nationalist credentials in an attempt to get a gig with the US government, as Jeff Rosenheim, the Metropolitan Museum of Art's photography curator told the New York Times.

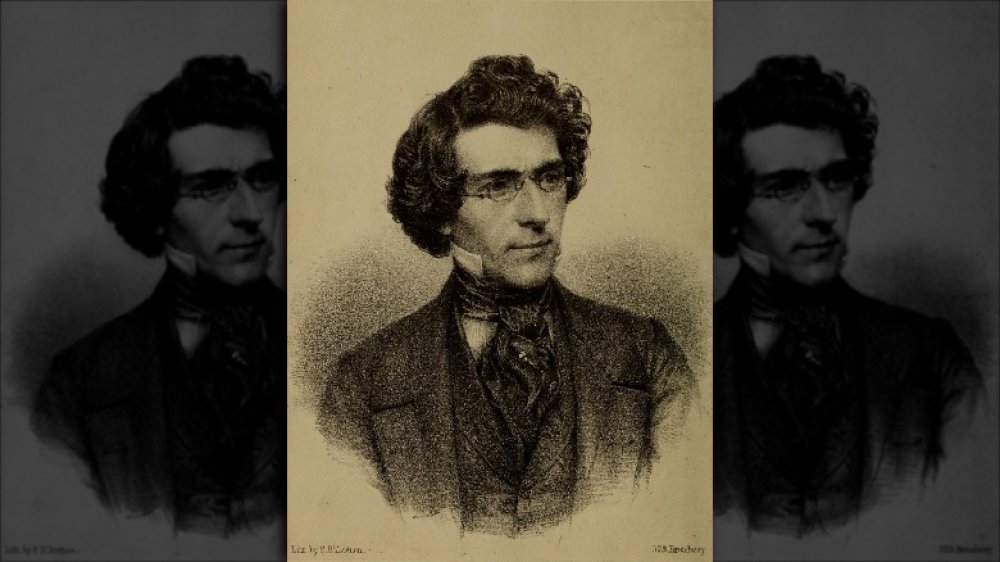

Mathew Brady learned photography from the best

Though we know little about where he came from, we do know for sure that Mathew Brady arrived in New York City in the 1830s, around the age of 16. His official Library of Congress biography notes that he started out as a department store clerk, but he had much bigger aspirations. After learning a bit about daguerrotypes and the newly emerging art of photography courtesy of making some display boxes and other paraphernalia for various New York photographers, as History.com relates, Brady got interested in the new art form. He seems to have taught himself a bit of technique and proved pretty good at it but knew he could get better.

Fortunately, Brady had some art and industry connections in New York courtesy of a chance meeting in upstate New York as a teen, as the American Battlefield Trust points out. So he hooked up with one of the pioneers of the technique for classes: Samuel Morse. As Roy Meredith describes in Mr. Lincoln's Camera Man, Morse wasn't just the inventor of Morse code, but also a devoted practitioner of photography and proponent of various other new technologies. He learned daguerrotyping from its inventor, Louis Daguerre, and soon taught Mathew Brady all he knew. Brady, in turn, was a quick study and opened his own studio right on Broadway within just a few years. In no time, he was winning awards, and becoming known as the go-to guy for fancy portraits.

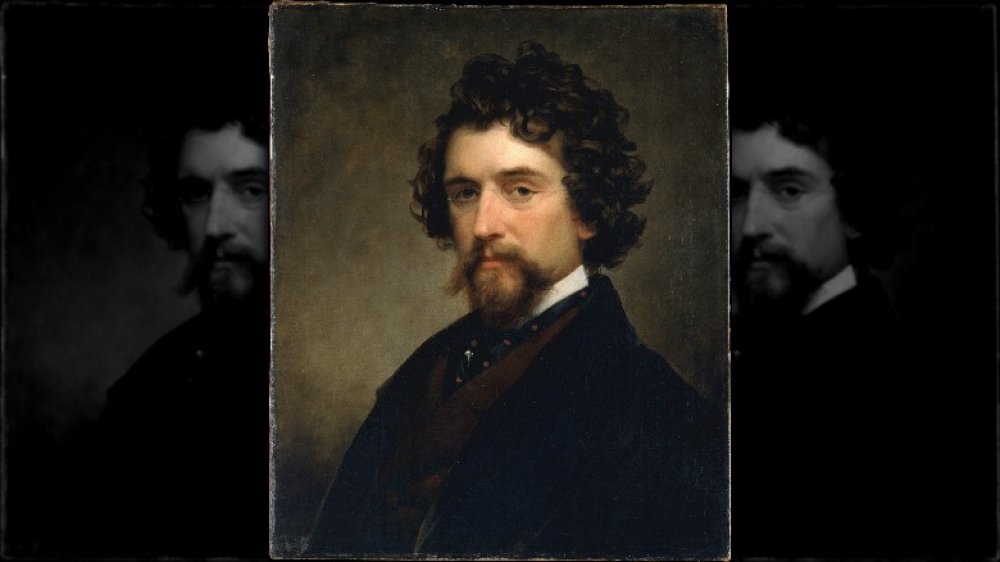

Mathew Brady was a portrait artist to the stars

Less than five years after first picking up a camera, Mathew Brady was not just taking pictures of celebrities, he was becoming a celebrity in his own right: "Brady of Broadway," according to History.com.

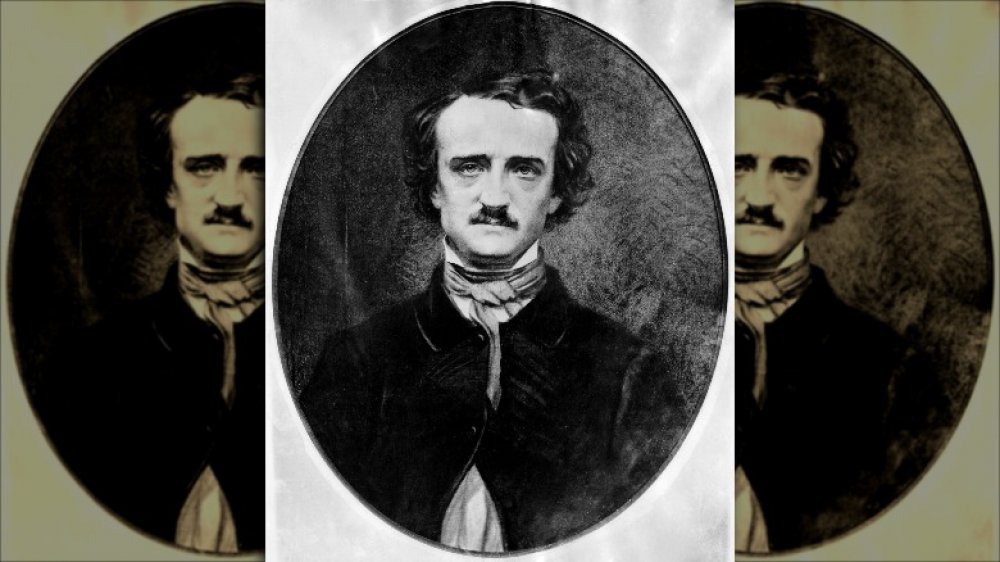

In no time, he was winning awards — he pretty much swept the American Institute's photography competitions for years, as the American Battlefield Trust notes. Perhaps more importantly, he had his studio sessions booked out months in advance by celebs who flocked to work with him. From politicians to writers and actors, Brady photographed anyone who was anyone in 1850s America. If you've seen period photographs of Edgar Allan Poe or Andrew Jackson, you've seen Brady's work, as the Getty Museum highlights.

He also started winning international awards for his work in the 1850s, including a gold medal at a London competition, as History.com notes. But his major accomplishment in that period was publishing a 12-portrait collection he called The Gallery of Illustrious Americans, as his International Photography Hall of Fame biography highlights. The book sold for $15 at the time — the equivalent of $400 today. Talk about a coffee table flex.

Mathew Brady may have helped get Abraham Lincoln elected

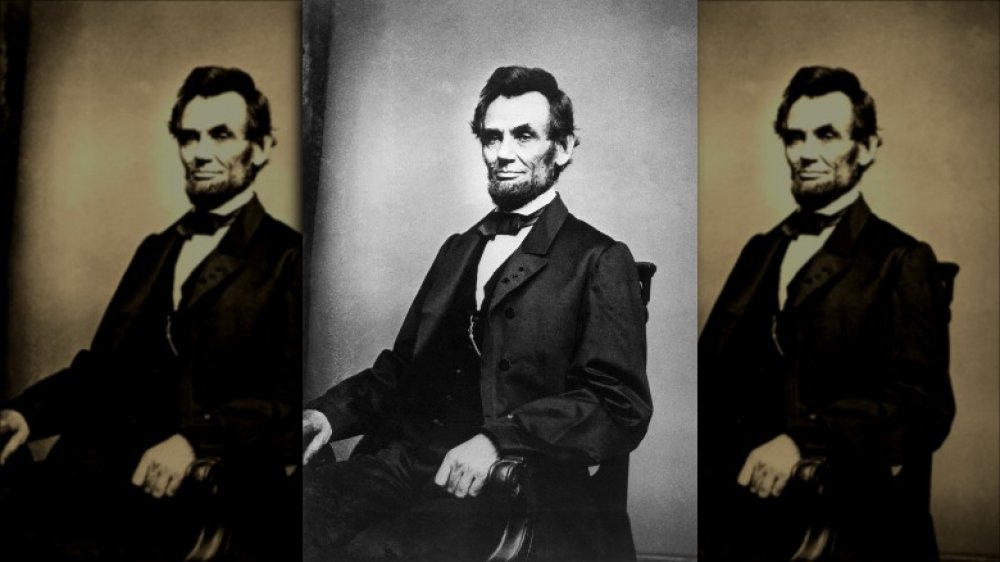

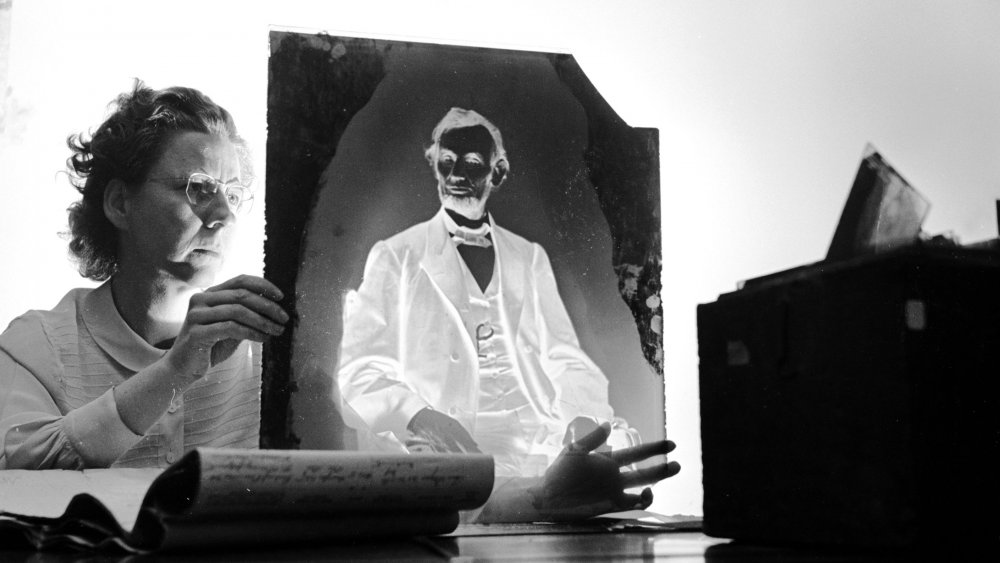

One of Brady's most famous subjects was Abraham Lincoln, and one of his portraits may have actually helped get Lincoln elected. Being a so-called country bumpkin born in a log cabin wasn't actually all that appealing to the movers and shakers of the 1800s political world. Honest Abe was more of a running joke among the New York, Boston, and Washington elite. As Smithsonian Magazine relates, Lincoln knew he had a serious image problem ... and saw Brady of Broadway as his ticket to enter high society.

By portraying the country lawyer as a serious gentleman, Brady helped change media depictions of the presidential candidate to a more positive light. Even Lincoln gave Brady credit for turning around his campaign, saying that "Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me president." The image Brady took, of a tall, slim Lincoln dressed in somber black and looking dignified as all get-out, was reproduced in basically every influential publication at the time and quickly made Lincoln one of the most recognizable men in the country, as the Metropolitan Museum of Art notes.

Brady would remain Lincoln's preferred portrait artist for the rest of the president's life, taking many photos, both composed and slightly more candid. He also took what essentially amounted to crime scene photos of Ford's Theatre after Lincoln's assassination, at the request of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, as the Ford's Theatre relates.

Mathew Brady photographed almost every president of his lifetime

Having established himself as the go-to guy for presidential portraits with his work for Lincoln, Brady ended up photographing or copying portraits of nearly every president who was alive during his own lifetime: a whopping 19 of them. From John Quincy Adams to William McKinley (presidents 6 through 25, if you're counting), Mathew Brady collected nearly the full set, as Mental Floss relates. The only one he missed was William Henry Harrison, president #9, who died of illness only a month into his term and never managed to get his portrait done.

He managed to pull this off by moving his primary studio from New York to Washington D.C. to be closer to the movers and shakers who paid his bills and gave him access to other celebrities. According to the Library of Congress, Brady opened his National Photographic Art Gallery in Washington, D.C. in 1858, quickly establishing himself as an essential stop for any visiting politician or foreign dignitary.

But Brady wasn't satisfied with taking egotistical studio portraits of politicos. He wanted to be part of documenting history itself, commenting: "From the first, I regarded myself as under obligation to my country to preserve the faces of its historic men and mothers," per Politico.

Mathew Brady was the "father of photojournalism"

Being based in Washington D.C. had its perks when it came to accessing the halls of power, but it also had some drawbacks. Namely, Mathew Brady was in the thick of things when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Brady had clearly known that trouble was brewing for some time; "Mr. Lincoln's Camera Man" had access to gossip and intrigue that others likely didn't, as author Roy Meredith highlights throughout his book. Given his fierce patriotic sentiments and devotion to Abe Lincoln as both a client and friend, it was natural for Brady to want to lend his talent to the war effort in some way.

But as ImprovePhotography.com notes, Brady suffered from degenerative poor eyesight and would have made a pretty crappy — and short-lived — soldier. Instead, he threw his energy into documenting the war for the nation to see. Open Culture relates that he started by simply offering to take portraits of soldiers before they shipped out, just in case they never came back. But soon he was making plans to move beyond the studio, shooting in the field and recording the true costs of war for a nation that was largely insulated from the bloodshed.

He received special permission from President Lincoln to document the war and, in 1861, began his efforts. As the International Photography Hall of Fame relates, Brady became the first person to completely document a war in images and, thus, the "father of photojournalism."

Mathew Brady didn't take most of his own war photos

Yet plagued by that lousy eyesight, and possibly just plain concerned for his own life, Mathew Brady didn't actually take most of the pictures for which he became internationally famous. Instead, as the Library of Congress notes, Brady hired a team of photographers to go out in the field on his behalf, as well as filling a shop full of retouchers and developers back in Washington. In essence, he created one of the first journalism bureaus.

Unfortunately, Brady's pursuit of truth in images didn't extend to truth in credit. Almost every photograph was attributed as his own work, even though the images of the First Battle of Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, and more were taken by his corps of 15-20 photographers, as the Encyclopedia Britannica admits.

Still, Brady succeeded in his main aim: bringing the horrors of war to a broader audience. In his 1862 exhibition, The Dead of Antietam, Brady stunned the nation by showing frank depictions of corpses on the battlefield. As a New York Times article of the period related, "Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it."

Mathew Brady went bankrupt from his photojournalism

Attempting to document an entire war wasn't a cheap affair and Brady paid the price, literally. He spent more than $100,000 of his own money — in 1860s dollars, no less — and had to declare bankruptcy, per NPS. Though creating a photo bureau allowed him to gather more images, without risking his own neck in the field, paying all those salaries out of pocket wasn't cheap. Plus, as the American Battlefield Trust relates, Brady was also snapping up prints, plates, and glass negatives from private photographers and pretty much anyone with a battlefield image to sell. His hope was to create the most comprehensive collection of war images possible so that no aspect of the conflict would be forgotten. Open Culture notes that he accumulated more than 10,000 plates by the end of the four-year war.

But war photos aren't like coffee-table books of influential politicians and celebrities. Where Brady had been able to sell his early portrait work for big bucks, he couldn't seem to find a taker for his war archives. According to the International Photography Hall of Fame, his exhibitions were critically acclaimed and well attended, but ticket sales didn't come close to scratching the surface of his investment. And a deal to sell the archive to the New York Historical Society fell through at the last minute, leaving Brady facing bankruptcy just a few years after he seemed to be on top of the world.

Despite his success, Mathew Brady died depressed and penniless

Unfortunately, Mathew Brady had been so sure that his Civil War work would be not only a historical landmark but also a profit center that he'd bought much of the complicated equipment on credit, as the Encyclopedia Britannica points out. Unable to keep up with the payments, he had to sell off his gear, then his studios. Worse still, the financial panic of 1873 took the last of his savings and forced him to declare bankruptcy, and then, to top things off, his beloved wife Julia died in 1884. And although Brady didn't take the majority of his battlefield photos himself, he did witness some of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War and apparently had difficulty recovering from the horrors he'd seen.

Eventually, Brady couldn't even afford to store his archives; the War Department scooped them up at auction for a paltry $2,840, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. That dismally unfair figure was eventually topped up to $25,000 by a Congressional order after some serious maneuvering, as the Library of Congress relates. Still, it wasn't nearly enough to cover Brady's actual debts.

Brady never quite got back on his feet. He slipped into a deep depression, possibly also due to his already lousy eyesight becoming worse and keeping him from the work he loved. Broke and heartbroken, he died after being hit by a streetcar in New York City in 1896, as Mental Floss notes.

Mathew Brady's work appeared on the $5 bill

Despite dying broke, Brady's work ended up worth a fortune, in more ways than one. Available to view at the US National Archives, as well as in collections at the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Getty Museum, and more, Brady's work and collections are highly sought after by historians.

Moreover, that early portrait of Lincoln wasn't the only one Brady took. Several of his snaps were later converted to etchings that would appear on versions of the US $5 bill, as My Modern Met reports.

Of course, there's a swirl of intrigue around even this part of Mathew Brady's life and legacy. According to Dusty Old Thing, there's a strong possibility that Brady was up to his usual tricks in claiming credit for portraits taken by an employee at one of his studios. So although the Lincoln penny and the $5 bill alike may have been modeled on portraits taken at a Brady studio, they may not have actually been staged, photographed, or developed by Mathew Brady himself.

Just one more question about the life of a man who devoted himself to taking stark, incontrovertible pictures of grim reality, but who remains a mystery himself.