The Untold Truth Of Charles Curtis, The First US Vice President Of Color

Americans love the word "first," which is why we obsessively track the firsts that occur in our own history. Every first represents progress, and that's never truer than in the field of politics, where representation literally equals power. So it's no surprise that Kamala Harris has captured everyone's imagination. She's the first female vice president, after all—and the first woman of color to hold that position. But note the qualifier: Harris is not the first person of color to be Vice President of the United States. That honor goes to the often-overlooked Charles Curtis, who served as Herbert Hoover's VP from 1929 through 1932.

Curtis' slow fade from our collective memory is both surprising and totally understandable. On the one hand, his status as the first person of color to serve as vice president came at a time when vice presidents weren't considered particularly important. On the other hand, considering the fraught history of race in this country you'd think someone like Curtis would have been a major focus of attention.

Whatever the reason for his low historical profile, Curtis has an assured place in the American story. Here's the untold truth of Charles Curtis, the first US vice president of color.

Charles Curtis was a member of the Kaw Nation

One of the most remarkable things about Charles Curtis is his status as an American of color. As the Encyclopedia Britannica notes, Curtis was one-quarter Kansa (sometimes called Kaw) Indian. That's not so remarkable, but the fact that Curtis rose to become one of the most powerful politicians in the country way back in the 1920s and 1930s—a period of our history not known for its racial tolerance and sensitivity—is remarkable.

Curtis was born in Kansas before it was even a state, in 1860 when it was still known as the Kansas Territory. Curtis' mother, Ellen, had mixed Indigenous American ancestry, including links to the Kansa, Osage, and Potawatomi Indians. That means that Curtis was one-quarter Kansa Indian. When Ellen passed away when Curtis was just 3-years-old, he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents on the Kaw Indian Reservation. The Washington Post notes that the first language Curtis spoke was Kansa.

As you might imagine, life on an Indian Reservation in the late 1800s wasn't a very peaceful or settled life. The Kaw were embroiled in disputes with several other tribes, and Curtis moved back to the city of his birth, Topeka, in 1868 to live with his paternal grandfather. Britannica notes that just a few years later the Kaw were moved to Oklahoma, and today there are only about 2,000 Kansa Indians.

He was the great-grandson of Kaw Chief White Plume

When we think of the history of Indigenous Americans in this country, we tend to think of endless conflict. The 19th century is marked by many bloody battles between the expanding American nation and the native people they were displacing. But not every Indian Chief saw war as the only option when the Americans turned up on their land. Some saw the coming domination of these European invaders as inevitable, and tried to negotiate the best future they could.

One of these was the Kaw Indian Chief White Plume—who was the most famous Kaw Chief, and Charles Curtis' great-grandfather. According to CNN, White Plume met and offered to assist the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804. A few years later, as noted by the Kaw Nation, White Plume traveled to Washington and was recognized as the leader of the Kaw Nation by the U.S. Government—despite not actually having ultimate authority over the tribe. White Plume believed the only way for the Kaw to survive was to make an accommodation with the Americans. He negotiated a treaty that ceded almost all of the Kaw land to the Americans in exchange for annual payments and livestock control.

Today, a large proportion of the Kaw Nation in Oklahoma trace their heritage directly to White Plume—the Native American Chief directly related to one of our Vice Presidents.

Charles Curtis was a famous horse jockey as a teenager

Charles Curtis' early life was unsettled. His mother died when he was just 3-years-old, and he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents on the Kaw Indian Reservation. Life there was chaotic, as the Kaw were feuding with other tribes. According to The Washington Post, Curtis was sent to live with his paternal grandfather in Topeka as a young teenager—and he grew rebellious. His grandfather attempted to discipline him, but Curtis was difficult to rein in. He'd learned how to ride a horse back at the reservation (he could even ride bareback), and Curtis parlayed this skill into a fledgling career as a jockey. He quickly became famous as "Indian Charley."

The local criminal elements in Topeka loved to bet on Curtis. Once when he won a big race a woman who ran a bordello in town bought him a whole new suit of clothes and a new jockey outfit as a token of thanks for winning a race she'd bet on.

His career as a jockey ended when the Kaw Nation was forced to move to Oklahoma—he was still officially listed as part of the reservation, and he tried to move to Oklahoma with his grandparents. His grandmother told him to go to school instead—setting Curtis on the path that would eventually lead him to the White House.

His political career was sensational

It's very unfortunate that Charles Curtis was overlooked for so long, because he was an immensely talented man. Once Curtis settled down to pursue a career in law, his advancement was rapid. As noted by KCUR, Curtis was admitted to the Kansas Bar in 1881 at the age of 21. Just three years later when he was 24-years-old he won his first election, becoming Shawnee County Attorney. The state had strict prohibition laws against alcohol at the time, and Curtis was reportedly very effective in enforcing them.

Curtis was an effective campaigner who kept notes on everyone he met so he could recall personal details about them when they next ran into each other. This discipline helped him be elected to the House of Representatives in 1893. Then, as The Washington Post reports, Curtis was appointed to the U.S. Senate in 1907. He lost his senate seat in 1913, but won the next election in 1914, returning to the senate. He became a force in that chamber, eventually rising to be Republican Majority Leader.

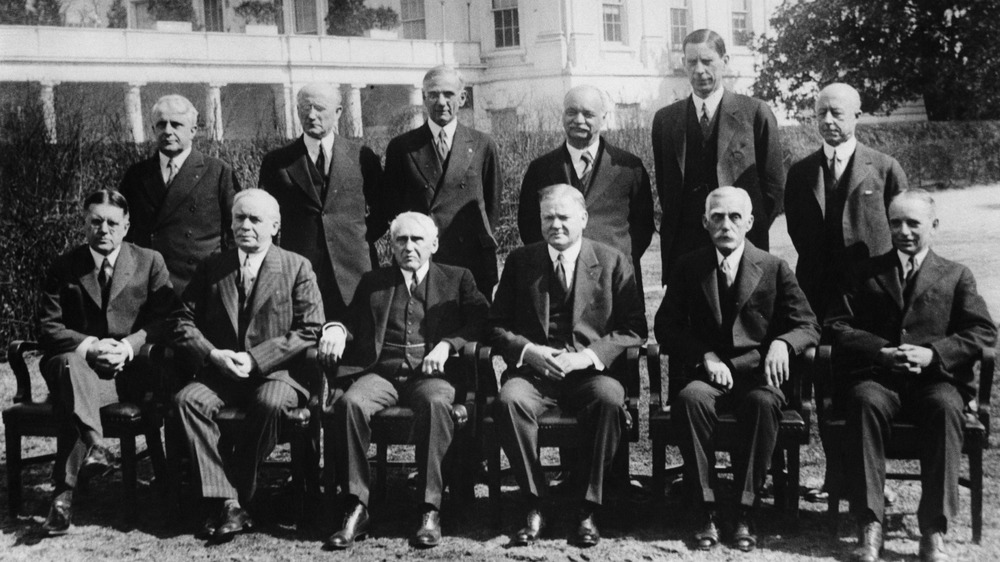

In 1928, Curtis threw his hat into the ring to be the Republican candidate for president. He couldn't gather enough support, but the eventual nominee, Herbert Hoover, needed support from the Midwestern states and knew Curtis could help him with that. He invited Curtis to be his running mate, and in 1929 Curtis became the first person of color to serve as Vice President of the United States.

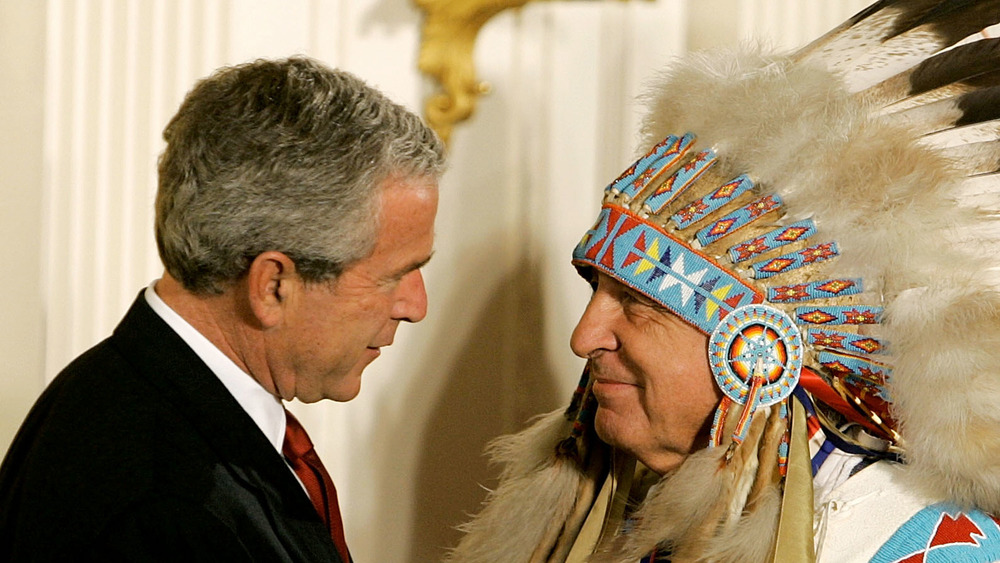

Charles Curtis played up his Indian heritage

It may have come to your attention recently that the United States is not a post-racial society just yet. If things are as bad as they are in 2020 in terms of race relations here, you can imagine how much more terrible they were in 1929. So you might think one reason so many of us were unaware that Charles Curtis was part Indigenous American was because he kept it on the down low over fears of racist attacks.

Not at all. In fact, as The New York Times reports, Curtis flaunted his Indian heritage—and it worked for him politically, despite the fact that people were approximately 110 percent racist at the time. While campaigning for office, Curtis liked to say things like he was "one-eighth Kaw Indian and a one-hundred percent Republican" or that he'd risen from "from Kaw tepee to Capitol," which aren't the sort of things you say when you're worried about racists being racist towards you. He also kept a lot of Indian memorabilia in his office to remind anyone who came in that he was Kaw, and even frequently posed wearing a feathered Indian headdress.

In other words, Curtis made no attempt to hide his status as a person of color, and it didn't hurt his career one little bit.

He was instrumental in destroying many Native American tribes

You might think that as part of the Kaw Nation, Curtis must have been very sensitive to the plight of Indigenous Americans and a staunch defender of their remaining rights and territories. But you'd be wrong—Curtis actually has a very complicated and not particularly positive legacy when it comes to the conquered Indian Nations of this country.

As KCUR reports, Curtis' main legacy from his time in the House of Representatives is the Curtis Act of 1898. This law removed tribal governments and gave authority over the tribal membership to a Washington committee, and broke tribal lands into small parcels that were then sold or assigned to specific individuals.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the Curtis Act was a death blow to the sovereignty of the remaining Indian tribes, as they were no longer able to enforce their own laws. This paved the way for Oklahoma to become the 46th state in 1907, but it came at the expense of the last vestige of Indigenous independence. As The New York Times writes, this law complicates Curtis' legacy as a member of the Kaw Nation, with many modern-day Kaw troubled by his role in the dissolution of their power and lands.

Charles Curtis was a big supporter of women's suffrage

When Charles Curtis was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1893, women could not vote in the United States. When he was elected to the senate in 1914, women still couldn't vote in the United States. While no one would accuse Curtis of being a secret progressive, he was forward-thinking on this particular issue.

As noted by the U.S. Senate's official page on Curtis, he held every single leadership position in the Senate as a member of the Republican Party, and used his growing influence to fight for the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. This included leading the floor fight, the spirited debate in the senate surrounding passage of the law.

If you're tempted to think that Curtis led the charge on women's suffrage for political gain, consider this: According to History, in 1923 Curtis once again led the charge for women's rights by sponsoring one of the earliest versions of the Equal Rights Act—a law that still hasn't been adopted to this day. Whatever flaws Curtis may have had as a politician and a leader, one area where he was far ahead of his contemporaries was in the assumption that women deserved an equal place at the table when it came to choosing our country's leaders and weighing in on the policies that define us.

Charles Curtis wanted to be president

One thing you can say about Charles Curtis: The man was ambitious. After a fairly humble childhood being shuffled between grandparents on the Kaw Reservation and grandparents in Topeka, Curtis launched a stellar political career. He suffered a few setbacks—according to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia he lost his first attempt to become a Representative in 1889 by a single vote—but for the most part achieved a steady rise through the ranks that saw him become Majority Leader of the Senate in the 1920s.

In 1928, Curtis thought he saw an opportunity. The Republican Party didn't have an obvious choice to run for the presidency, and after Herbert Hoover performed poorly in early primaries he hoped a deadlock in the voting would give him the opening to become a dark horse candidate—a strategy that had worked in other nomination battles in the past. When other candidates dropped out, however, support coalesced behind Hoover; according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Curtis placed second in the nomination vote.

All was not lost, though. Hoover wanted to cement support from the farming states of the Midwest, and thought the popular Kansan would be ideal to balance the ticket, so he invited Curtis to run as his vice presidential candidate. Hoover and Curtis won in a landslide in November, 1928—just a few months before the Great Depression crashed into the country.

Charles Curtis wasn't given much to do

As noted by History Collection, there was no love lost between President Herbert Hoover and Vice President Charles Curtis. During the battle for the nomination, Curtis had attacked Hoover mercilessly over his perceived disconnection from the common man. Hoover knew that there was truth in those attacks, which is one reason he put aside personal animosity and invited Curtis to be his running mate. Curtis provided Hoover with a link to those "common folk" that balanced the ticket.

Once in office, however, the relationship soured. According to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia, Hoover gave Curtis very little to do in his official role as Vice President. After attending a few cabinet meetings and coming away with zero authority or responsibilities, Curtis stopped showing up for meetings. Hoover never complained.

When the Great Depression slammed into the country, Curtis went from a nonentity to an active detriment to Hoover. Curtis stubbornly insisted that the Depression was merely a temporary fluke in the world economy, and at one point said that "good times were just around the corner." That phrase was a huge mistake; as the Depression ground on it was used repeatedly to paint the Hoover administration as out of touch and unconcerned about the misery afflicting millions of Americans. In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Hoover for the presidency, and Curtis retired from politics.

He was the first Vice President to open the Olympic Games

When Curtis became Vice President in 1929, he probably thought it was another steppingstone in his career—that perhaps the presidency would be his in four years. As it turned out, it was the last political office Curtis would hold. Not only did the Great Depression come and make any chance that he and Hoover would be reelected slim at best, but his relationship with Hoover deteriorated almost immediately. The President stopped giving Curtis anything meaningful to do. The only duties that came Curtis' way were ceremonial things of little importance.

One of these ceremonial duties remains notable, however. As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, when Los Angeles hosted the Summer Olympics in 1932, Hoover opted not to attend and sent Curtis to open the Games instead. The Olympic Charter stipulates that the Games be opened by the head of state of the host country, which means most Olympiads are opened by monarchs and presidents. Curtis became the first American Vice president to open an Olympics.

While this is not as important a "first" as being the first Vice President of color, it's still notable that as you scan the list of kings, queens, and presidents who have opened the Olympics you'll find Charles Curtis' name.

Thousands attended Charles Curtis' funeral

If you're just now discovering Charles Curtis and the fact that he was the first person of color to serve as Vice President of the United States, you might think the reason he's so obscure is because he wasn't particularly well-known or popular.

Of course, to get elected to the House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and then the Vice Presidency requires a certain level of notoriety and popularity. Curtis was an excellent politician and campaigner. His term as Vice President coincided with the advent of the Great Depression, and his poor relationship with President Herbert Hoover made it difficult for Curtis to achieve much. As a result, he left office at a low ebb in terms of his personal and political popularity.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Curtis went back into private practice as a lawyer after leaving the White House. As often happens when politicians retire, however, he experienced a resurgence of goodwill. He died of a heart attack just four years later. As The New York Times notes, his body was transported by train back to Kansas, where thousands of people turned out to pay their respects.

It was more than 60 years before another indigenous American was elected to the senate

Charles Curtis broke a racial barrier so easily, and with so little drama, that people didn't really notice for decades. Far from a problem for the politician, Curtis made his Indigenous American heritage front and center in his campaigning, somehow defusing any possible racist attacks against him at a time when organizations like the Ku Klux Klan operated openly and had immense influence on politics and public policies.

Charles Curtis wasn't the first Native American senator to be elected in the U.S. As noted by The Dispatch, Robert Owen, a Cherokee, was Senator from Kansas from 1907 until 1925. But to put things in perspective, after Curtis left the senate to become the first Native American Vice president, it was more than six decades before another Indigenous American became a senator.

As KCUR reports, Curtis was the last Native American senator in the country's history until 1992, when Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a Cheyenne, was elected as junior senator from Colorado. Campbell served two terms as senator (switching political parties in the middle), and was the only Native American in Congress during that time. While there hasn't been another Native American senator since, as of 2020, there four Native Americans in the House of Representatives (with a fifth joining the chamber in 2021).