This Is What It Was Like To Be A Survivor Of America's Last Slave Ship

Until Dec. 6, 1865, it was completely legal for Americans to own another human being and work — or beat — them to death. On that day, the 13th Amendment was ratified, saying (in part), "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude ... shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Less well known is another law, one that took effect on Jan. 1, 1808. That one abolished the African slave trade.

According to History, the first slave ship made its way into Jamestown, Va., in August of 1619. For the next 60 years or so, most of the forced labor actually came from indentured servants shipped over from Europe. As that supply dwindled and the need for workers increased, the slave trade from Africa hit almost unthinkable highs. Between 1680 and the 1770s, it's estimated that English ships alone brought at least 3 million people into a life of slavery in the U.S.

By 1807, there were around 4 million people trapped in slavery. Lawmakers deemed the population to be self-sustaining, as those born into slavery were also slaves, and voted to abolish the African slave trade on Jan. 1, 1808. The law passed, but there was one more ship — and this is the story.

The final journey of the Clotilda

By 1860, the African slave trade had been outlawed for 52 years, and transporting people by ship from their homes in Africa to a life of slavery in the U.S. was an offense punishable by hanging.

Enter Timothy Meaher. Meaher, says The New York Times, was the wealthy owner of a steamship company, and it was on one of these ships that an argument broke out between passengers. The debate was over whether or not it was still possible to bring a ship of slaves over from Africa. Hypothetically speaking, of course.

Meaher made it not-so-hypothetical and also made a bet that he could do it... and he did. The Clotilda set sail under Capt. William Foster and picked up 110 people from an area we now know as the nation of Benin. Those 110 people had been kidnapped from their homes, villages, and families, only to be selected by the captain and his cronies to be shoved onto the ship and taken to Alabama. After they were unloaded, Foster set the Clotilda on fire in an attempt to destroy the evidence of their crimes. Meaher, it turned out, had won his bet at the expense of dozens of lives.

Here's what it was like on the journey

The journey of the Clotilda ended up being one of the best-documented of all slave ship journeys. Capt. William Foster kept a journal, and Timothy Meaher himself later boasted of the whole thing to everyone from neighbors to journalists.

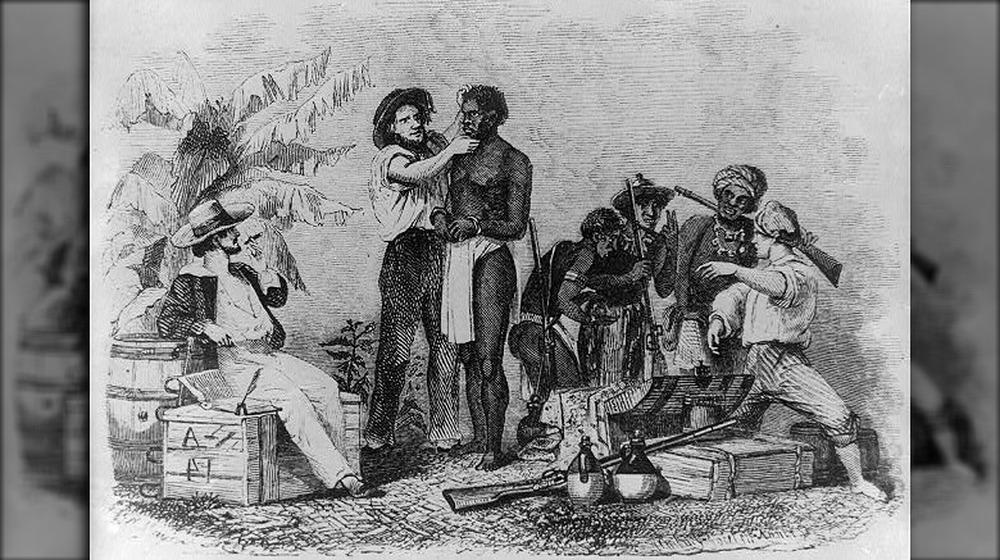

According to National Geographic, the men, women, and children who were selected by the slave traders for the Clotilda were from different regions and ethnic groups across Nigeria and Benin. Most had been kidnapped, some by the slave-trading Dahomey. They were soldiers, traders, farmers, and families, all of whom were examined from head to toe and hand selected.

Then, it was a neck-deep wade out to the Clotilda, where they were ordered to strip. In theory, it was to maintain cleanliness, but in reality, it was a little more about the humiliation.

The journey was horrific. Everyone was kept in the hold for the first 13 days by a crew terrified they were going to get caught. Later, survivors who spoke about the trip remembered the stifling, unbearable heat, the unending darkness, the filth, and the thirst. Every person was rationed a daily, single swallow of water that tasted like vinegar, and meals were nothing more than "molasses and mush." Sickness was widespread, and by the time they spotted land, two people were dead.

Hopes dashed

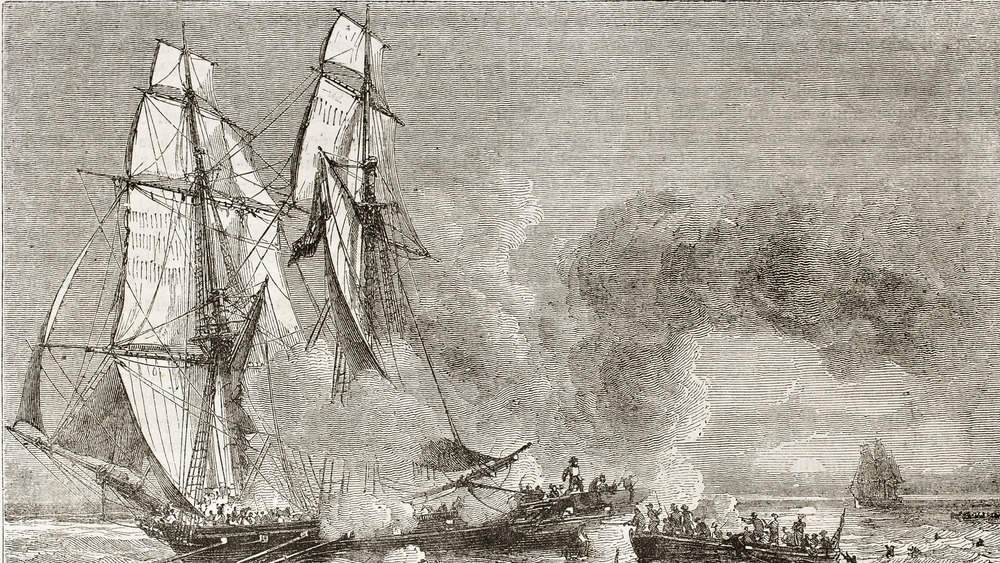

The Clotilda had left the U.S. in either late February or early March, and on July 8, a tugboat was pulling the slave ship up Mobile Bay (pictured). The slavers' human cargo was transferred to a steamboat owned by Timothy Meaher's brother, Burns, and then taken to a plantation owned by John Dabney.

Capt. William Foster took care of the evidence that was the Clotilda, setting fire to the five-year-old schooner that National Geographic described as being in the sort of condition that was unmistakable for anything but a slave ship.

The people it had transported into a life of slavery, meanwhile, where shuffled from one place to another in an attempt to stay ahead of the authorities. They were "clothed" in corn sacks and rags, fed meat and cornmeal that made them violently ill, and were pushed onward ahead of the law. The authorities did know — Meaher and Foster had tried to keep the whole thing a secret, but word had, of course, gotten out.

Federal authorities had dispatched the U.S. Marshals to track down Meaher's newest possessions, but they could never quite catch up. When they hit Dabney's plantation, they had already been moved on to another plantation, this one owned by Meaher's brother. The captives knew, too, and later remembered how close it had been, with one person saying they had "almost grieved themselves to death."

What happened to the survivors when they arrived?

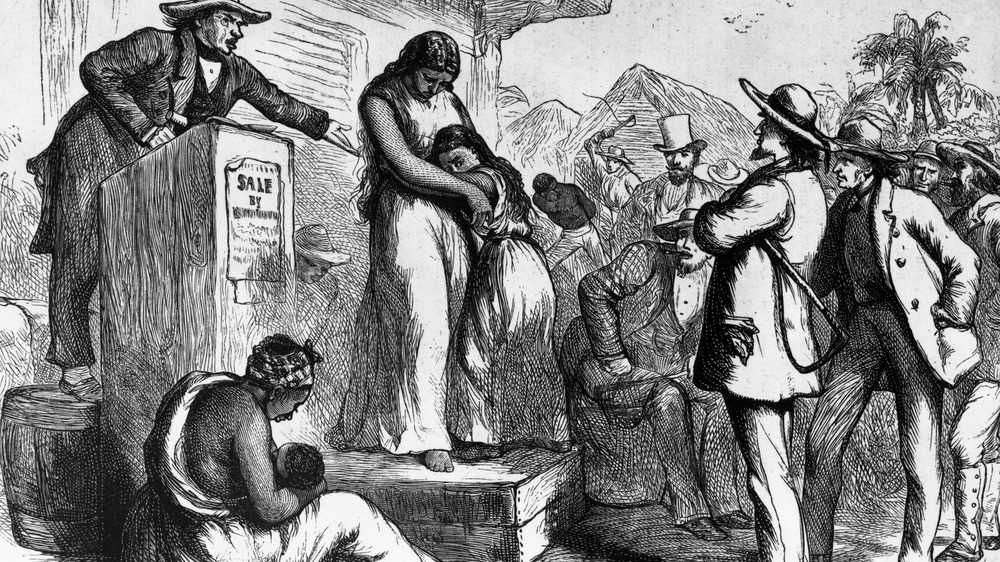

Then, there was the question of what to do with the people Timothy Meaher had won his bet with. There were 80 people taken to Mobile, Ala., and put up for sale in an auction Meaher had organized, and 25 people were spotted — and reported by — the Mercury newspaper. On July 23, 1860, the paper reported that a group of people of "pure, unadulterated African stock" were seen walking through the Alabama countryside, and there's a heartbreaking footnote here. Along the way, they passed a circus, and when they heard the trumpet of the elephant, they started screaming in their native tongues, "Home! Elephant!"

National Geographic says Meaher kept 16 men and 16 women for himself, while his brother took 20 and Capt. William Foster was given 16. They were also arrested for running an illegal slave ship, but since the slaves in question weren't found, Meaher, his brother, and the plantation owner John Dabney were cleared of all charges. Foster was ordered to pay a $1,000 fine for not paying the duties on his ship's "imports."

The survivors stood together in solidarity

The people of the Clotilda were often sold in groups, and for some, that meant they continued to share a special kind of strength and solidarity, formed on board the ship.

Noah Hart was another slave who was working on Timothy Meaher's plantation when he brought in his new group of slaves from the Clotilda, and he remembered (via National Geographic) that this new unit never fought or argued amongst themselves and never started any trouble or fights with anyone else in their new home. They did, however, make it clear that if trouble happened, they were going to end it. When Meaher's cook slapped one of the young Clotilda girls, her scream brought her new family running... with sticks and garden tools in hand. The cook ended up quitting. Another instance of resistance happened on the plantation belonging to Meaher's brother. When his overseer went to whip a young Clotilda woman, he very quickly found the lash was taken away and used to beat him bloody.

They also helped each other observe traditions — from burial practices to tattooing — that their people had long practiced, which allowed them to hold onto pieces of their identity.

Not everyone was sold in groups, though, and for the individuals who were sold alone, they would later remember they were treated particularly badly. They didn't speak English and couldn't understand what was wanted of them.

Born to be loved by all

In 2020, National Geographic profiled the last surviving member of the Clotilda. Her name was Abake, which meant "born to be loved by all," but she was renamed Matilda when she was sold to Alabama state representative Memorable Walker Creagh.

Her story started long before that. She was only a 2-year-old toddler when she, her mother, and her sisters were taken captive by Dahomey warriors, dragged to a nearby slave port, and selected for the Clotilda. While she didn't remember the trip, her mother spoke about it often — and never forgot the death of her nephew. The family was separated when they reached the U.S. — Matilda and her sister, 10-year-old Sallie, stayed with their mother. Her two older sisters were sold separately, and she never knew what happened to them.

Freedom came for her, her family, and the rest of the South's slaves in 1865, and she soon gave birth to her first baby — the child of a white man. She was just 14. Two more children would quickly follow. After settling in Martin Station, Ala., Matilda, later known as Matilda McCrear, had seven more children with a German bookbinder-turned-deputy sheriff. Eventually, she was able to afford to rent her own farm. She watched her children grow up, settle around her, and took a stand — she demanded recompense from the government for her abduction. She was denied.

She moved to Selma in 1937 and died in 1940. She was the last known survivor of the Clotilda.

Sold as a child bride

Before scholars uncovered the story of Matilda McCrear, there was another woman who had been thought to be the last survivor of the Clotilda. Her name was Redoshi, and she was 12 years old when her father was murdered, and she was taken from her home in West Africa by his killers. From there, it was the Clotilda, America, and chains.

Her name was changed to Sally Smith, and she would eventually tell her story to Zora Neale Hurston (via The New York Times). Once in the U.S., she was put up for sale, paired up with a man who had also been taken from his family. They were auctioned as husband and wife, and she started her days as a slave on a Bogue Chitto, Ala., plantation.

The 13th Amendment was passed five years later, but Smith chose to stay with the Smith family — the family who had bought her. It wasn't uncommon, and she later explained in a newspaper interview that she had opted to stay where she knew the people were going to treat her kindly.

Near the end of her life, she was filmed for a Department of Agriculture film called The Negro Farmer: Extension Work for Better Farming and Better Living. That makes her the only known person to have lived through slavery to also have been filmed. She never saw it. The film was released in 1938, and she died in 1937.

Cudjo Lewis: Finally telling his story

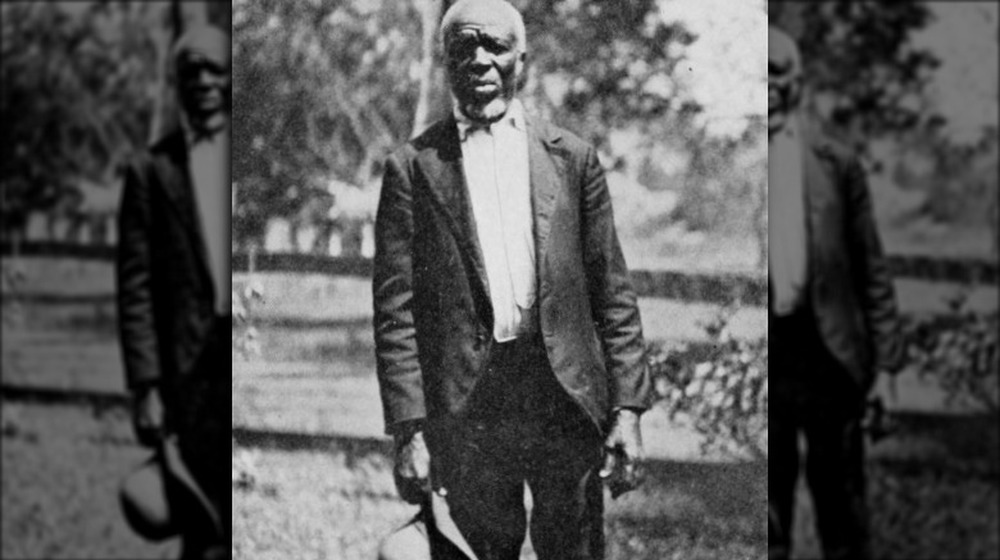

Zora Neale Hurston spent a lot of time with Cudjo Lewis, starting in 1927 (via NPR). He was in his 90s when he spoke to her and told her the story of how he'd come to the U.S. on a slave ship. Hurston wrote a book based on his life, but the Independent says that when she submitted it to publishers in 1931, no one wanted it. It wasn't until 2018 that the book was finally published, and he could truly tell his story.

It started when he was 19 years old and still going by his given name, Kossula. A group of female warriors massacred his village, made captives of those they could sell, and killed those they couldn't. Then, he ended up on the Clotilda where, says History, everyone was a stranger... at first, and by the time they made landfall in the states, he'd found solidarity with new friends and family, bound by hardship. He quickly found himself cruelly separated from them and was so despondent, he said, "I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama."

There was still more isolation after he was sold and after he was taken to the plantation where he was to be put to work. He wanted to talk to the other slaves, he remembered, but they couldn't understand each others' languages — and he was alone even there.

Cudjo Lewis: Alone, alone, and alone again

His name was changed to Cudjo Lewis, and he was bought by Timothy Meaher's other brother, Jim. He had considered himself fortunate (via the Independent), because while there were definitely beatings, they were fewer and farther between than they were for Meaher's own slaves.

He spent five years as a slave before the ratification of the 13th Amendment, and when word came that they were free, he told Meaher that he wanted the land they'd been working as payment for taking them from their homeland. Meaher refused to give up the land, but finally, a group of former slaves earned enough money to buy some property of their own.

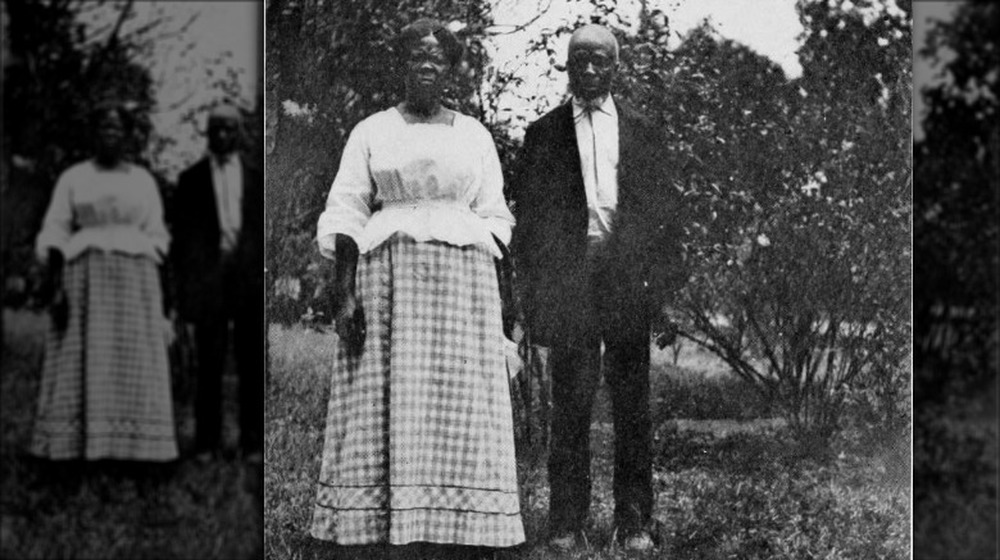

Lewis married a woman named Abila (pictured), and they had six children — but suffered immense tragedy. One by one, he watched his children die. There was sickness, accidents, and one — also named Cudjo — was shot and killed by a police officer. NPR says that by the time he sat down to tell Zora Neale Hurston his story, his wife and all of his children were gone. In spite of being a respected community elder known affectionately as Uncle Cudjo, he was lonely. Until the day he died in 1935, he wanted one thing — to return home, where he said he still hoped he would hear someone call his name, or say, "Yeah, I know Kossula."

The founding of Africatown

The survivors of the Clotilda were held as slaves for five years and then, they were free. Those who lived in close proximity to each other remained close, and they shared one more thing — a desire to return home.

According to the Smithsonian, though, there was a problem. They didn't have the money. So, they did the next best thing, and it's a true testament to teamwork, perseverance, and hard work. They work in mills and on farms. They sold vegetables and earned whatever they could. The money went into a pool, and they bought land from the man who'd bet he could steal them away from their homes in the first place. On that land, they built a new home and called it Africatown.

It was founded in 1866 (or, some sources say, 1868), and by the middle of the 20th century, The New York Times says the town had grown into a place anyone would love to live. Work was good — jobs at a nearby paper plant and a handful of mills were plentiful — and the fishing was even better. Unfortunately, all good things must come to and end. By 2019, the population had dropped to around 2,000 from 12,000, many of the mills and plants that had supplied valuable jobs were closed, and abandoned patches of town were becoming overgrown. Those who still lived there didn't want to give up, though — for many residents, it was the town founded by their ancestors.

Continued resistance, continued pressure

Even after the 13th Amendment gave the last survivors of that final slave ship their freedom, they continued to face incredible resistance — including harassment from Timothy Meaher himself.

The 1874 election was a contentious one, and Alabama newspapers urged voters to "answer the roll call of white supremacy." Meaher was right on the front lines, and according to National Geographic, he tried to pressure his former slaves — men who had been naturalized citizens since 1868 — to vote pro-slavery. Pretty sure that they wouldn't, he resorted to other methods to stop their vote. After he told officials at the polling stations that they were foreigners, some were turned away. Others, he tried to physically block from voting. Instead, they opted to walk the five miles to Mobile to place their vote — which they needed to pay to do. They kept their voting receipts for decades, treasured possessions that showed how far they'd come.

Today, National Geographic says that perseverance continues, and dozens of their descendants living in Africatown are still going up against oppressors. Africatown now sits in what's ominously called Alabama's Chemical Corridor, a patch of the state where 26 chemical companies sit along a stretch of river just 50 miles long. At the same time they're fighting cancer and other diseases and illnesses caused by major industries, they're also fighting those same companies — and hoping to make their town a cleaner, better place.

A desire to tell the whole story

In 2019, Lorna Woods spoke with NPR about Africatown founder Charlie Lewis, her great-great-grandfather. For a long time, it simply wasn't something her ancestors spoke of. Now, though, she's ready to tell their story — and the discovery of the wreckage of the Clotilda was just the things they needed.

According to the Smithsonian, the Clotilda was discovered after a massive joint search between groups that specialize in finding historic wrecks, including the National Museum of African American History and Culture's Slave Wrecks Project (SWP). SWP co-director Paul Gardullo said this about the search: "This is a way of restoring truth to a story ... Justice can involve recognition. Justice can involve things like hard, truthful talk about repair and reconciliation."

Those living in Africatown are hoping that the discovery of the wreck will not only shed light on the story of their ancestors but help them to revitalize the town. According to the Associated Press, it's possible that the Clotilda's discovery may do more than that and open the door for formal reparations to be made.

As for the Timothy Meaher family, they're still around, too. Meaher's great-grandson responded to National Geographic's request for a statement, who pointed out that there were no convictions. He adds, "Slavery is wrong, but if your brother killed somebody, it would not be your fault. I'll apologize. Something like that, that was wrong." He has also declined to meet with the descendants of those the Clotilda brought to America as slaves.