These Mobsters Were Never Brought To Justice

There are several reasons why bringing mobsters to justice has long proved more challenging than eating a cannoli without oozing cream cheese everywhere.

First, most mob victims are also mobsters, and snitching on other mobsters to law enforcement — even if they killed your guy — is not just dishonorable, it's dangerous. Second, the other kind of mob killing tends to involve people who have somehow become witnesses to mob crimes. Third, sometimes mobsters are also cops, and vice versa. (For example: The Departed.)

This explains why many of the most famous mobsters were never brought to justice, at least not for their most outrageous crimes. But then again, as some of them learned, the mob has its own brand of justice, and it's probably worse than prison. From the boss of bosses who overreached, to mobsters whose charges were mysteriously dropped, to the family head who retired to Arizona, meet the mobsters who did the crimes but not the time.

Joe the Boss avoided jail but not assassination

Giuseppe "Joe the Boss" Masseria was famous for dodging convictions. He moved to the United States from Sicily in 1886, aged 16, to escape a murder charge. He and an associate later shot their Mafia boss — and two bystanders, including a child — in front of a police precinct, but the case never made it to court.

In 1928, Masseria kicked off what the FBI refers to as the Castellammarese War — a campaign to take over all the New York families and become the capo dei capi, the boss of bosses. But in 1931, two of his intended victims, Charles "Lucky" Luciano and Salvatore Maranzano, teamed up and had Masseria shot in the back of the head while he was eating dinner at a restaurant on Coney Island. The New York Times reported that the restaurant owner was so scared that he gave his fingerprints to police in case he was murdered — and he was.

According to the FBI, this made Maranzano the boss of bosses. He put the "organize" in organized crime, creating the New York mob's Five Families and coining the name La Cosa Nostra to describe the American Mafia. Luciano became head of the then-Luciano and now-Genovese family. When Maranzano put a hit on him, Luciano got there first, having Maranzano shot dead in his office months after Masseria's death.

Vincent Mad Dog Coll beat murder charges but not murderers

There are certain crimes even mobsters balk at — which is what made Vincent "Mad Dog" Coll so dangerous.

During Prohibition, Coll became a notoriously violent enforcer for bootlegger Dutch Schultz. However, Coll's reckless side hustles eventually led them to war. He got a stern warning after robbing the Bronx's Sheffield Farms dairy without Schultz's permission. But he really blew it in January 1931 when he got arrested and Schultz paid the bail, only for Coll to skip trial and then refuse to repay the money.

Coll also had an idiotic habit of kidnapping other mobsters for ransom. That July, a child was killed during a failed kidnap attempt of a Schultz lieutenant that turned into a shootout. Coll was put on trial for the murder but was acquitted in December. Meanwhile, either his kidnapping racket or an attempt to murder Lucky Luciano had enraged other mob high ups. With Schultz, they collectively put a $50,000 price on his head.

On Feb. 8, 1932, Coll was shot dead while using a payphone in a chemist's office. According to the Chicago Tribune, a police officer near the scene commandeered a taxi cab and chased the killers at the high speed of 65 mph, but they escaped in traffic.

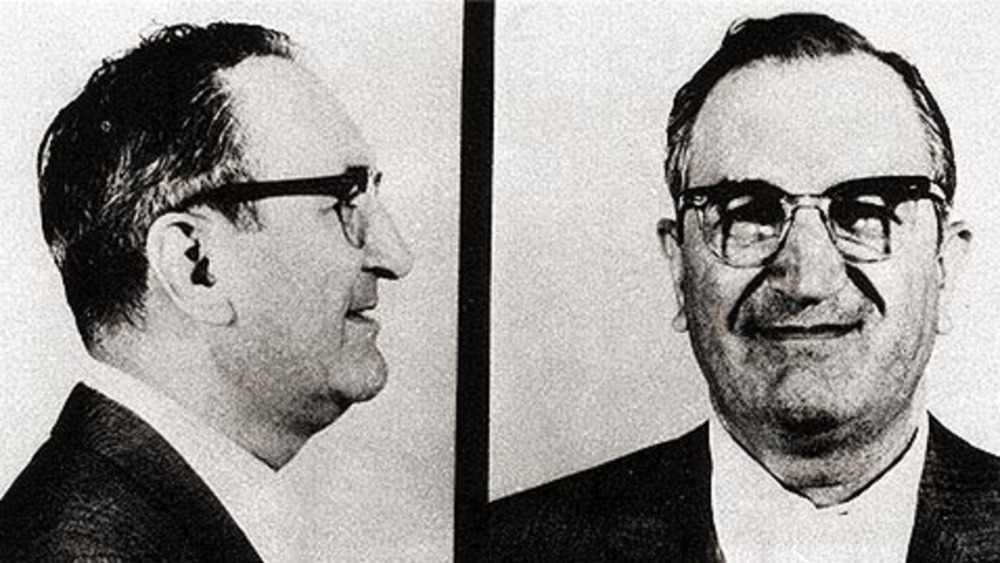

Meyer Lansky was too shrewd to get caught

You didn't need to be the head of one of the Five Families to exert power in the Mafia. For 40 years, Meyer Lansky masterminded the organization's corruption of labor unions, corporations, and politicians while earning millions for himself from illegal operations.

Jewish Lansky was born Maier Suchowljansky in a Russian-owned region of Poland and emigrated to New York to escape the pogroms in 1911. He formed a gang with Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel — their activities escalated from running a craps game to stealing cars, burglaries, and liquor smuggling during Prohibition, and then kidnap and murder. The pair established a group of hitmen that later inspired the Mafia's more formal hitmen branch, Murder, Inc.

These activities drew attention from the Mafia. Lansky and Siegel worked for Joe Masseria and then Lucky Luciano. Lansky helped the latter establish a nationally organized syndicate in 1934, according to the New York Times. He funneled most of the money he made into gambling but also into prostitution, drug trafficking, extortion, and racketeering, as well as several legitimate businesses.

The law tried to come for Lansky without much success, aside from a few short jail terms. In 1970, he moved to Israel to escape an indictment from a grand jury, a move that worked until the Israeli government reluctantly extradited him in 1972. The charges on tax evasion, conspiracy, and skimming were all ultimately dropped. Lansky died of cancer, aged 81, in 1983.

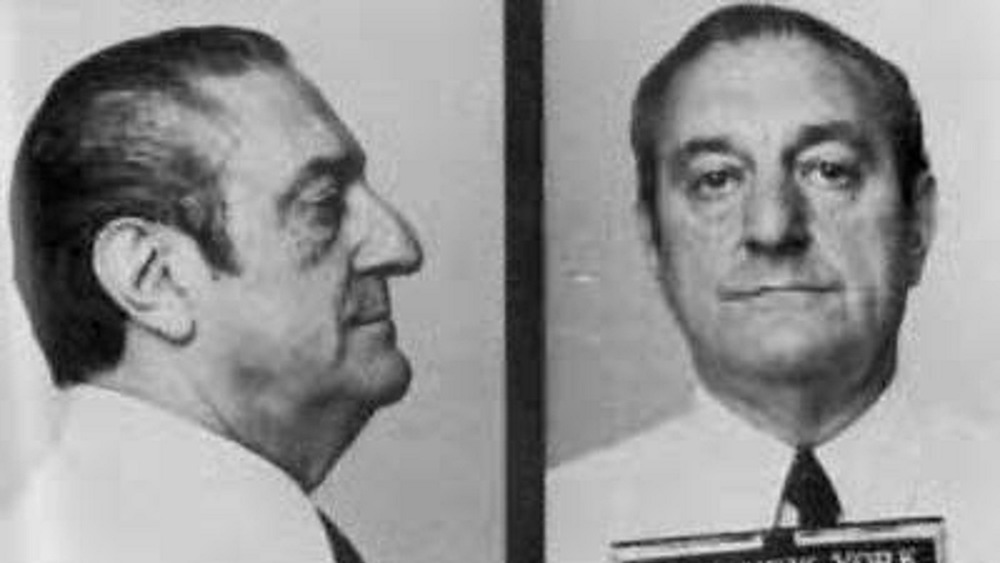

Albert Anastasia survived death row

Albert Anastasia got away with murder for decades as the leader of Murder, Inc. — the hitman department of the Mafia — during the 1930s and 1940s. Anastasia was one of several mobsters who turned against Joe the Boss during the Castellammarese War and is even rumored to have been one of his killers. Lucky Luciano rewarded Anastasia by making him second-in-command — the underboss — to Vincent Mangano's family (now the Gambino family.) But Anastasia wasn't about to settle for second place. The New York Daily News reports that on April 15, 1951, Mangano not-so-mysteriously disappeared, leaving Anastasia in charge.

An FBI document from 1952 notes that Murder, Inc., assassin-turned-police informant Abe Reles identified Anastasia as the one who pulled the trigger in at least 30 murders, saying he ordered dozens more. One of Anastasia's specialties was intimidating witnesses into withdrawing their testimonies — and killing them if they refused. (Possibly including Reles.) This was how he escaped five murder charges, including one in 1921 that sent him to death row at Sing Sing.

However, five years after that FBI report, Anastasia fell victim to his fellow mobsters' power lust. Then-underboss Vito Genovese overthrew his own family head Frank Costello and ordered Anastasia's underboss, Carlo Gambino, to kill Anastasia. He was shot dead while in a barber shop in 1957. As the Russell Daily News drily observed, "The gunmen succeeded where countless prosecutors had failed."

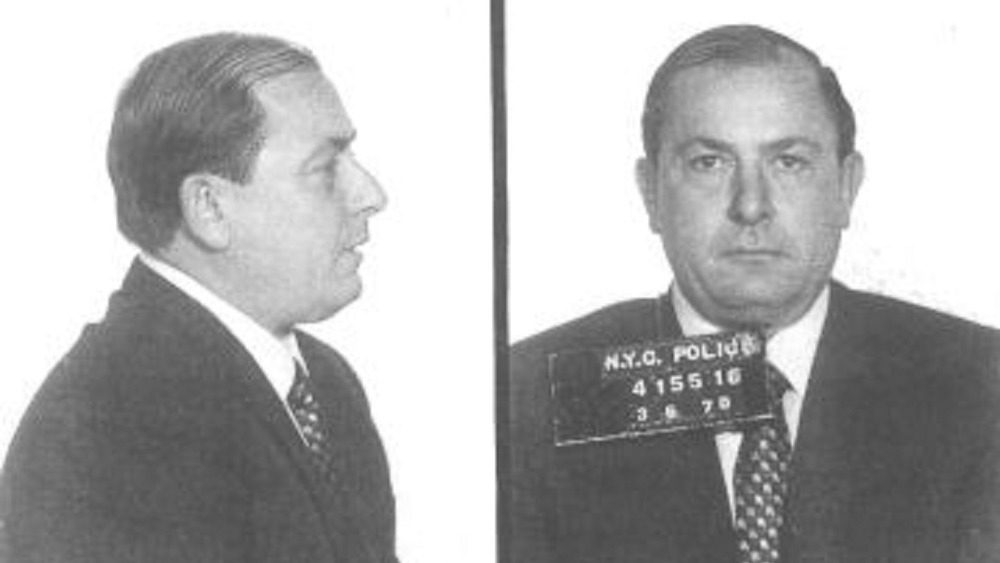

Carlo Gambino kept a low profile at the top

Under Carlo Gambino's watch, the family that still bears his name became the most powerful Mafia family in the country. Gambino took over from Anastasia in 1957 and exerted influence over the Five Families in New York and the national organized crime body known as the Commission, which set rules and mediated disputes for all 26 American Mafia families.

The New York Times reported that Gambino's Mafia family was made up of about 500 made men and 500 associates and that their territory stretched from western Massachusetts to outer Philadelphia. The Gambino family's major moneymaker was labor union racketeering, including hijacking, as well as gambling, loan shark operations, and drug trafficking.

Unlike other Mafia bosses, Gambino kept a low profile. This may explain why, in his five decades of organized crime — including serving under Masseria, Maranzano, Mangano, and Anastasia before shooting his way to the top job — he only spent 22 months in jail, between 1937 and 1938. That's not for lack of trying on the law's side. According to the New York Times, in 1970 Gambino was indicted as part of a plot to hijack a car carrying $3 million, but the trial was canceled because Gambino had a serious heart condition. He had a heart attack later that year, which prevented a deportation order being carried out, and died in 1976 of natural causes.

Paul Castellano's murderers pre-empted the courts

After Carlo Gambino's relatively mundane death in 1976, his brother-in-law and underboss "Big Paul" Castellano reputedly took over the family business.

Castellano didn't totally avoid prison during his mobster career. In 1957, he was charged with contempt of court and served seven months over the Apalachin Meeting, a national gathering of Mafia families. Ironically, Castellano's desire to avoid future charges may have ultimately got him killed. Or it could have been his failure to keep out of court.

In 1985, Castellano was indicted by the federal government on 78 counts of racketeering, murder, car theft, and prostitution, and also faced indictments for extortion, bribery, narcotics, murder, and conspiracy, the New York Times reported. He was accused of heading a Mafia car-theft ring that moonlighted in murders. At the time, Castellano had ordered his family to halt narcotics operations, as he felt they were attracting too much attention, which displeased underboss John Gotti.

On Dec. 16, 1985, with the trials underway, Castellano and his underboss, Thomas Bilotti, were shot dead. The FBI's theory was that the Five Families' bosses had agreed to have Castellano killed, since his legal troubles were bringing too much attention, and/or that Gotti had grown frustrated with his boss and ordered the hit. It was probably the latter. Gotti became the next Gambino boss, ruling until 1992, when he was sentenced to life in prison for planning Castellano's murder.

Joe Bonnano claimed kidnap to avoid trial

"Retirement" is not exactly common practice among New York Mafia bosses. But Joe "Joe Bananas" Bonanno pulled it off.

According to the LA Times, Bonanno took over — and renamed — the Maranzano family after original boss Salvatore Maranzano was murdered (on Lucky Luciano's orders) in 1931. Unlike other families, he spurned prostitution and drug dealing in favor of bookmaking, union racketeering, airport heists, and loan-sharking operations.

The family flourished until the late 50s, when Bonanno became increasingly paranoid about his fellow bosses, and they grew increasingly frustrated with his stubbornness. Ultimately, the tension led Bonanno to flee New York, leaving his son in charge of the family. He officially retired to Tucson, Ariz., in 1968, aged 63.

Bonanno wasn't a complete stranger to the law. The New York Times reports that he was indicted by a grand jury over the Apalachin Meeting of national Mafia heads in 1957 but was spared from the trial thanks to a heart attack. The convictions were ultimately overturned. In 1964, facing another trial, he disappeared, turning up 19 months later, claiming to have been kidnapped. In his 70s and 80s, Bonanno served a total of two years and two months between 1980 and 1986, for conspiracy to obstruct justice and refusal to testify in a racketeering case. Considering all the illegal operations he'd been involved in, that's not bad. He died in 2002, aged 97 — probably a record for a Mafia boss.

Tommy Lucchese escaped deportation

Not all Mafia bosses came to power by murdering the previous boss (or at least attempting to.) Gaetano "Tommy" Lucchese loyally served as underboss to Tommy Gagliano for 20 years, between 1931 and the latter's death from natural causes in 1951. According to the New York Times, Lucchese was the more public figure of the then-Gagliano family, which was renamed Lucchese during his reign.

Lucchese got his start in organized crime during the Prohibition era, working with Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky. It was then that he served his only prison sentence – a year, starting in 1921, for car theft. He was arrested several more times, including for murder, but never charged. This came back to haunt Sicilian-born Lucchese in 1952, when he was nearly deported for lying about the charges on a naturalization form. However, six years later, the Supreme Court dismissed the U.S. attorney general's attempts to have him deported.

Under Gagliano and Lucchese, the family became the most powerful of the Five Families. They were involved in racketeering in the trucking and garment industries, gambling, extortion, and heists. You may know them from the Goodfellas airport heist, which happened 11 years after Lucchese died from a brain tumor in 1967.

Joe Colombo hid his crime behind a so-called civil rights campaign

Joe Colombo portrayed himself as a real estate mogul and a champion of Italian-American civil rights. As the New York Times reported, he founded the Italian‐American Civil Rights League in 1970 to advocate for a positive image of Italian Americans. As opposed to, say, newspaper articles accusing an innocent real estate mogul such as himself of being a mobster. He even convinced a producer on The Godfather and several public officials to remove references to the Mafia.

However, others would tell you that Colombo was the leader of the Profaci family, which was later (in a rather blatant move) named after him. In the 70s, the family was seen by some as second only in power to the Gambinos and was involved in the usual Mafia operations — loansharking, hijacking, gambling, and racketeering.

Colombo's so-called civil rights campaigning ensured him a spot on the FBI's most-watched list. In December 1970, the agency seized a briefcase containing suspicious documents, forcing him to testify before a grand jury. Colombo tried to stay tight-lipped, but the damage was done. Relations with the other families — and even his own — soured, and in June 1971, he was shot at a rally. Paralyzed, he survived seven more years but not as the boss. His would-be assassin, Jerome A. Johnson, was shot dead on the scene. It's believed someone in Colombo's family or one of the others ordered the hit, but who and why is unknown.

Tony Accardo reportedly got away with a historic crime

If anyone can get away with being a mob boss for over two decades, it's the guy who may have been involved with the most infamous Mafia crime in history.

As the Chicago Tribune reports, on Feb. 14, 1929, five men disguised as police detectives burst into a garage on the northside of Chicago that was used by mobster George "Bugs" Moran to store illegal liquor. They ordered the seven men inside (Moran wasn't there) to line up against the wall and opened fire with a small arsenal.

No one was ever arrested for the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, but it's believed that the notorious thug Al Capone arranged it — crippling Moran's operation made him the de facto leader of the Chicago Outfit. Capone was imprisoned for tax evasion in 1931. But the man who supposedly took over some of his gambling interests and later his entire gang, Tony Accardo, never was.

Multiple people believe Accardo's rise to power started when he took part in the massacre. According to the LA Times, Accardo acknowledged that he'd met Capone but denied being a mob boss. He was sentenced to six years in prison for the same crime as Capone in 1960, but the conviction was overturned. And he repeatedly pleaded the Fifth at appearances before the U.S. Senate's permanent subcommittee on investigations, which studies organized crime (among other things.) Accardo died of heart and lung disease aged 86 in 1992.

Sam Giancana couldn't get immunity from the mob

Sam "Momo" Giancana did a delicate dance with the law. Giancana was a driver and hitman for Al Capone. In the 1920s, he was arrested for auto theft but avoided prison and also managed to escape trial over three murder investigations. He was imprisoned for a few years starting in 1939 for illegally manufacturing alcohol.

Giancana replaced Tony Accardo as boss of the Chicago Outfit in 1957, according to the Chicago Tribune. Under him, the organization escalated until it controlled the city's prostitution, gambling, drug trafficking, and other illegal activities. Despite this, not all the authorities wanted to make him an enemy. The CIA has admitted that in the early 60s, it paid Giancana and another mobster $150,000 to assassinate Fidel Castro.

However, the net was closing, thanks in part to secret FBI recordings ordered by Attorney General Robert Kennedy and mobsters-turned-informants. In 1965, Giancana refused to testify before a grand jury investigating organized crime, and was sentenced to one year in prison. However, he was mysteriously released. The Chicago Tribune reported that it was supposedly on the order of U.S. Attorney Nicholas Katzenbach, in exchange for selling weapons to Israel.

In 1966, Giancana fled to Mexico, effectively giving up his leadership, but he was deported in July 1974. He reluctantly testified before another grand jury, in exchange for immunity, but was shot dead at home in June 1975 a few months later, apparently by fellow mobsters worried about loose lips.

It wasn't the law that came for Theodore Roe

Theodore "Ted" Roe made a fortune running a policy wheel in Chicago — an illegal lottery popular in the city's Black communities in the early 20th century. Gamblers picked three numbers from 78, and there were multiple draws a day, increasing your odds, although some of the wheels were not designed to play fair.

The policy kings — the people who owned and operated the wheels — became some of the Black communities' first millionaires. According to the Chicago Tribune, they protected their investments by paying politicians and law officials to look the other way and weren't above resorting to violence. But many also used their wealth to support the communities, becoming unofficial bankers for people turned down by racist mainstream banks. Roe was famous for paying hospital and funeral bills and handing out $50 notes.

However, things changed when the Italian mob took note of the kings' wealth and wanted in. Under Tony Accardo, they waged a violent war to take control of policy. Starting in the mid-1940s, the Chicago Outfit murdered and intimidated at least eight kings. But Roe fought back, literally. He killed a made man during a shootout, which only intensified the Outfit's determination to murder him. It succeeded in 1952, when he was shot on Michigan Avenue. The Outfit took control of policy, while a crowd of 7,000 gathered for Roe's funeral.