The Most Terrifying Christmas Characters Ever

Both a sacred observance of the Christian faith and secular celebration, Christmas is universally recognized as a time of peace and goodwill. Outside of its religious context, the holiday season, as celebrated in the West, is filled with merry characters with either a tenuous connection to tradition such as Santa Claus (the common interpretation of whom is based more on early 20th-century advertising than history) or cut out from whole cloth like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer – another Yuletide advertising icon. Regardless of the commercial roots of some of these uniquely American holiday characters, their intent, beyond selling soda or promoting department stores, is to inspire joy and wonder.

Despite being the most wonderful time of the year, the holiday season is not without a dark side. Incorporating elements of ancient festivals of death and rebirth, the modern Christmas celebration with its mistletoe and trees is haunted by its pagan past. The Victorians obliquely acknowledged the arcane aspects of the holiday. Christmas Eve ghost stories were a beloved tradition of the season and were as associated with the holidays as Kris Kringle. Yet, only Dickens' A Christmas Carol has survived as an example of the once common practice.

Throughout the world, many Christmas celebrations include figures that are downright diabolical. In many parts of Europe, monsters, witches, and demons provide a chilling counterpoint to Santa, Rudolph, and Frosty. You better watch out because the most terrifying Christmas characters ever are coming to town.

Krampus: from terrifying legend to modern Christmas icon

Krampus, the most well-known of all Yuletide monsters, has evolved from a relatively obscure figure of Central European folklore to a pop culture icon and universal symbol for Christmas cynics over the last couple of decades. Thanks to the internet, the legend of the Christmas devil has swept the world. The subject of numerous recent holiday horror movies, Krampus has become a veritable holiday industry in recent years with his horrible, horned image slapped on everything from wrapping paper to ugly Christmas sweaters.

However, Krampus' overexposure as of late has done nothing to blunt his frightening original story. As detailed by National Geographic, Krampus makes his rounds on the night of December 5. Those unlucky enough to encounter the Christmas devil on Krampusnacht will meet a creature who is the diabolical antithesis of St. Nicholas. A hulking, half-goat, half-demon beast with a long tongue, Krampus comes swinging a rusty chain and bells. Armed with a bundle of birch switches, he thrashes naughty children before dragging them off to hell. Other versions of the story maintain that Krampus eats or drowns misbehaving kids. By comparison, a lump of coal from Santa is getting off light.

Throughout much of the 20th century, Krampus was banned by German and Austrian authorities for his obvious resemblance to the common interpretation of Satan. Krampus' 21st-century comeback, however, is marked with wild parades called Krampuslauf in which revelers in elaborate Krampus costumes march through the streets of Austria, Germany, Slovenia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

Grýla, Iceland's Christmas witch

Described as an ogress and witch by Smithsonian Magazine, Iceland's Grýla rivals Krampus for sheer holiday terror. The earliest written accounts of Grýla date to 1300, but her origins in oral tradition may be far older, dating to the pre-Christian celebration of Jól (Yule).

The early Icelandic Yule celebrations were, in many ways, more akin to Halloween than our modern winter holidays. Against the backdrop of months-long winter darkness, Jól was a time to gather with friends and relatives both living and dead. Elves, trolls, and other creatures held sway in the grim winter. According to legend, these supernatural entities would don masks and visit the homes of unsuspecting people.

The most fearsome of these was Grýla. An ugly giantess with hooves and 15 (or even 40) tails, Grýla ("growler" in English) is said to descend from her mountain lair gathering bad children in her sack as ingredients for her favorite stew. Variations of the tale cast the child-hungry witch as a beast with multiple heads. Living with Grýla in her home in the lava fields of Dimmuborgir is her notoriously lazy third husband Leppalúði (she became bored with the first two and killed them) and her 13 sons, the mischievous trolls known as the Yule lads.

In the 18th century, tales of Grýla and her family were considered so terrifying that parents were officially forbidden to use the legends to frighten misbehaving children.

The mischievous Yule Lads

Although time has softened Iceland's Yule Lads, transforming them into jolly, elf-like pranksters, the original incarnations of the 13 sons of Grýla were far more frightening. There were also more of them. According to a 2018 article in Iceland Magazine, there were up to 82 Yule Lads in some of the oldest Icelandic legends. By the 1800s, the number was standardized to 13 to correspond to the 13 days of Christmas.

The Yule lads, though filthy and misshapen, are not murderous like their infamous mother. Their antics tend more toward petty theft and mischief. Each of the Lads' names correspond with their particular behavioral quirk. For example, Bjugnakraekir (Sausage-Snatcher), sneaks into houses and hides in the rafters, waiting for his moment to swoop down and swipe sausages. Among the stranger Yule Lads is Gluggagaegir (Window-Peeper), who looks through windows.

Despite their obvious creepiness, tales of the Yule Lads served a practical purpose as reminders to conserve food and supplies as well as to keep vulnerable children inside during the deadly Icelandic winters.

Over time, the Yule lads have evolved into benevolent Christmas sprites. Now considered good-natured mischief makers, the Yule Lads, clad in traditional Icelandic garb, function more like 13 Santa Clauses who leave treats in the shoes of good children and potatoes (sometimes rotten) in those of the naughty. Still, they retain their descriptive names as a reminder of their unsavory origins.

Wear new clothes on Christmas Eve or else...

In Iceland, if you escape Grýla's pot and manage to contend with 13 nights with the Yule Lads, there's one more terrible Christmas monster left to face – the fearsome Jólakötturinn (Yule Cat). Grýla's pet, the immense Yule Cat towers over the tallest houses and roams the countryside in search of food on Christmas night. However, this gargantuan tabby has no taste for kibble. The Yule Cat feasts exclusively on children who haven't received new clothes for Christmas. Peering through windows, the Yule Cat inspects the gifts of Icelandic children on the lookout for fresh holiday duds. If he spots anyone with old, torn, or threadbare clothing, he eats them.

According to Dr. Emily Zarka, host of the PBS digital series Monstrum, the most famous account of the Yule Cat is documented in the 1932 book Christmas is Coming by Jóhannes úr Kötlum. Kötlum writes, "His Whiskers sharp as bristles, his back arched up high, and the claws of his hairy paws were a terrible sight ... In every home, people shuddered at his name. If one heard a pitiful meow, something evil would happen soon."

Much like the Yule Lads, the Yule Cat served a socioeconomic purpose. "Because the Yule Cat only attacks people who do not receive new clothes, this monster likely emerged as a response to the importance of wool production," Zarka says, "scaring children and even adults into finishing their textile work before Christmas and the coldest part of the year."

Mari Lwyd, the skeletal Yuletide horse of Wales

Found in the Christmas celebrations of Wales, the Mari Lwyd's frightening appearance belies her mostly benevolent nature. Welsh for "Grey Mare," the Mari Lwyd consists of a horse's skull with shiny baubles for eyes and a colorful mane of ribbons. The Mari Lwyd is held aloft on a long pole by a person under a white sheet who operates the lower jaw.

Although no written record of the Mari Lwyd exists prior to 1800, some scholars believe her to be part of pre-Christian Celtic mythology. Conversely, as detailed by Wales.com, one version of the legend of the Mari Lwyd contends that she was a pregnant mare cast out of the stables to make room for Mary and the Christ child. According to this version of the myth, she now roams the Earth looking for a place to have her foal.

The eerie winter custom is most prevalent in the southern counties Gwent and Glamorgan, but it has spread throughout Wales. Festooned with lights and decorations, the Mari Lwyd is paraded through Welsh villages between Christmas and Twelfth Night in the company of a hostler and, in some regions, traditional folk characters including a fool and a Lady. The Mari Lwyd and her merry band go from house to house singing and engaging in bawdy rhymes with the occupants. Granting the Mari Lwyd entry to your home is considered good luck, although she may try to steal things and is known to snap her bony jaws and chase people she likes.

Belsnickel, the anti-Santa

The only scary Central European Christmas character to take root and thrive in the United States, Belsnickel originates in Southwest Germany. Described as a dirty, disheveled man dressed in rags, sometimes wearing a mask with an inordinately long tongue, Belsnickel functions as a rather disgusting and unsavory substitute Santa. His pockets are laden with treats which he scatters on the floor. However, kids who greedily lunge for the goodies too quickly find themselves on the business end of his enchanted switch.

German settlers brought Belsnickel to Pennsylvania, where the tradition continues. Belsnickel generally shows up in the weeks before Christmas, rapping on windows with his switch and demanding entry to homes with children. As detailed in a 2013 article in Allentown, Pennsylvania's, Morning Call, Belsnickel's main job is to remind recalcitrant youngsters that they still have a little time to mend their ways before Saint Nicholas' Christmas Eve visit. Often portrayed by a father, uncle, or other male relative who's conveniently indisposed during the visit, Belsnickel may quiz children on the prayer they're assigned to recite in church on Christmas morning or sing a song to save themselves from the sting of his switch.

In 2012, Belsnickel broke into the mainstream thanks to a holiday episode of the popular NBC comedy The Office. In the episode titled "A Dwight Christmas," Rain Wilson's Dwight Shrute turns Dunder-Mifflin's annual Yuletide party into a traditional Schrute Pennsylvania Dutch Christmas by dressing as Belsnickel.

You better watch out for Knecht Ruprecht

In the United States, Jolly Old Saint Nick makes his rounds solo, save for his team of flying reindeer. However, in Germany, he brings along some muscle to lean on the denizens of the naughty list. A close companion and assistant to Saint Nicholas, Knecht Ruprecht, covered in soot and ashes and clad in a dark robe or sometimes rags and tattered furs, trails behind his benevolent boss.

A forerunner of Belsnickel, Knecht (meaning "knight or servant") Ruprecht's origin varies from legend to legend. Some versions of his story maintain that he was an injured foundling saved from death by Saint Nicholas. Others cast him as a horned wild man who leaves the forest only at Christmastime.

According to the travel and culture website German Girl in America, on the evening of December 5 (Christmas is reserved for a visit from the Christ Child or Christkindl, the season's main bringer of gifts), Saint Nicholas visits the homes of children with his shadowy servant in tow. After consulting a book to see if the devil has written anything bad about a particular child, Saint Nicholas makes his decision. A clean record and a recitation of the Lord's Prayer means sweets and nuts, but if Old Scratch has taken some notes, a child may receive a lump of coal or a smack with a bag of ashes — or be stuffed in Knecht Ruprecht's sack and spirited away to parts unknown.

Frau Perchta is keeping an eye on your celebrations

Perhaps the most frightening and grisly of all German Christmas legends is that of Frau Perchta. Originating in Austrian folklore, Perchta was initially characterized as a beautiful, benevolent goddess. As detailed by Maria Alexander of TOR.com, Jacob Grimm, best known as one of the Brothers Grimm, the famous collectors of European fairy tales, wrote that her name means "Shining One." Grimm associates her original form with other moon goddesses of pagan European mythology such as Holda and Diana. Clad in snowy white robes, Perchta's only grotesque aspect is her large, misshapen "swan's foot," which belies her ability to shapeshift.

As Christianity took root in central Europe, Perchta began to be associated with the feast of Epiphany. She also underwent a physical transformation. Active during the 12 Days of Christmas, Perchta may appear in the aspect of a haggard crone with a long, hooked nose. Like Knecht Ruprecht and Belsnickel, Frau Perchta rewards good children who say their prayers and have worked hard all year with sugarplums and nuts. However, children and adults who incur Perchta's wrath face a gruesome fate. Perchta "the belly-slitter," cuts open the abdomens of those who fail to appropriately feast during the holiday season and replaces their entrails with straw, stones, and refuse. As Alexander writes, "Only a full, round belly was said to deflect her blade."

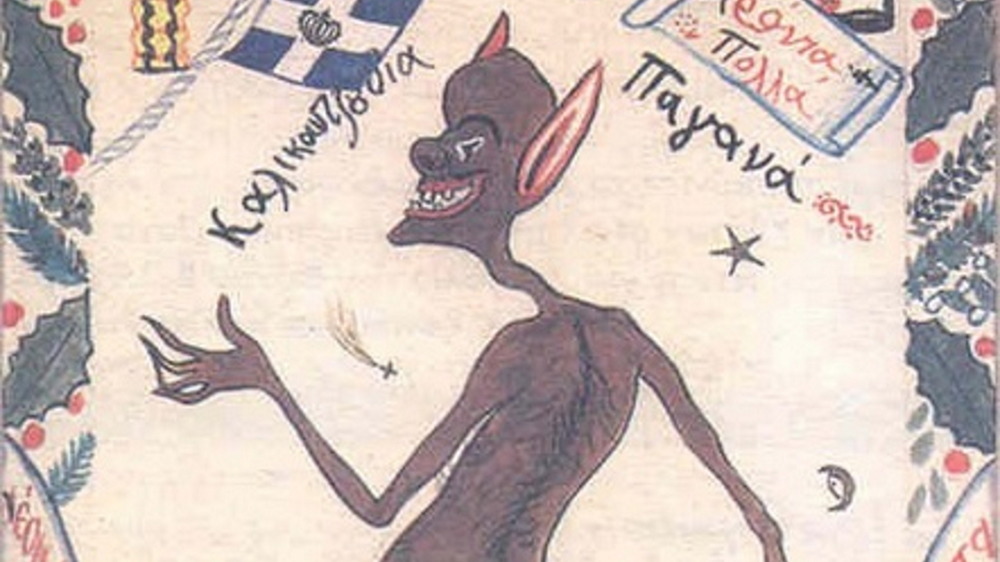

The Kallikantzaroi — Greece's Christmas goblins

Greek folklore maintains that deep within the bowels of the Earth is an enormous tree. Supporting the planet from within, the world tree is in constant danger of being felled by a gang of malicious goblins called the Kallikantzaroi, who spend the year hacking at its trunk. Hoping to destroy the Earth, they're tireless in their task. By December, they've nearly completed the job, but, during the 12 Days of Christmas, these vile beings lay down their tools and are allowed to roam the surface of the Earth and torment mankind.

According to John Tomkinson, author of Haunted Greece: Nymphs, Vampires, and other Exotica, the appearance of the dreaded Kallikantzaroi varies. Some accounts describe them as tall, ugly beings with blackened skin who wear heavy iron clogs on their feet. Other tales say they're squat gnomes with long arms, red eyes, and cloven hooves. On the loose during Christmastime, their behavior varies from merely mischievous to downright vile. "...They intimidate people, urinate in flower beds, spoil food, tip things over and break furniture," Tomkinson tells Spiegel International.

Fortunately, the Kallikantzaroi's time on Earth is short. Banished to their underground realm on Epiphany, they return to their task of felling the world tree, which has healed during the preceding 12 days.

Père Fouettard, France's Christmas bogeyman

Père Fouettard, translated as "Father Whipper," is, in many ways, a French analog to Germany's Knecht Ruprecht. He accompanies Saint Nicholas on his rounds and carries with him an armload of switches. As described in Christmas in France by Corinne Madden Ross, Père Fouettard wears a dirty, hooded cloak and a long, unkempt beard. Like Knecht Ruprecht and Belsnickel, he's used as a holiday threat to disobedient children. On occasion, French parents may remind their little ones that Père Fouettard has been known to drag children screaming from their beds in the middle of the night. As horrifying as that is, the real terror of Père Fouettard is in his origin story.

As documented by the Saint Nicholas Center, Père Fouettard is the reason that Saint Nicholas became recognized as the protector of children. According to legend, three small boys wandered from their home and became lost. A wicked butcher took the hungry, cold children in and slaughtered them for their meat. When Saint Nicholas found out about this heinous act, he resurrected the children and returned them to their parents. The butcher now eternally serves Saint Nicholas in repentance of his sins.

Hans Trapp is hungry for a holiday feast

Hans Trapp, yet another of Saint Nicholas' dark companions, has a history rooted in reality. Based in part on the story of real-life excommunicated knight Hans Von Trotha, Hans Trapp is part of the celebrations of the Alsace region on the borders of France and Germany.

As described by Mat Auryn on Patheos.com, Hans Trapp, a lawless blasphemer, was in league with Satan. Using black magic, he made pacts with demons to secure his lavish and decadent lifestyle. Cruel and vain, Hans Trapp's evil acts drew the attention of the pope, who excommunicated him.

Exiled to the forest, Trapp went mad and developed a craving for the flesh of children. Having slain a wayward child, Trapp was preparing to feast on his innocent prey when he was struck by a bolt of lightning and killed. Dressed as a scarecrow, his spirit wanders from house to house at Christmastime looking for bad children to eat. Now a companion to Saint Nicholas, he encourages the naughty to mend their ways or face a fate similar to his own.

The Grinch, the Grither, and killer Santas

Although the United States has only been around for a comparatively short time, the New World has more than made up for its lack of ancient lore with movies, stories, and television.

Take, for example, Dr. Seuss' Grinch. Featured in a 1966 animated TV special that has become an annual Christmas tradition for millions, this mean-spirited Yuletide villain is, in many ways, a direct descendent of Belsnickel and the Kallikantzaroi.

Another modern Christmas monster is the Grither. The subject of Michael Bishop's 1978 short story "Seasons of Belief," the Grither is a creature who lives in a shipwreck at the North Pole and who hunts down those who speak his name on Christmas Eve.

Santa Claus himself has taken a dark turn in American pop culture. Long before the current fascination with Krampus, killer Kris Kringles terrorized horror fans in movies, comics, and TV, with Christmas Evil and the unforgettable Tales From the Crypt episode "And All Through the House" being just two examples.