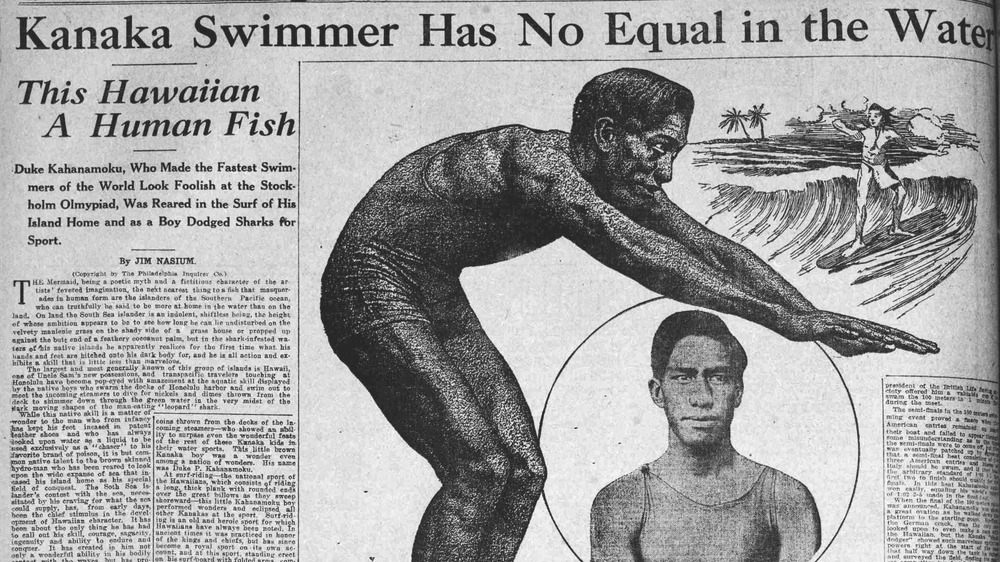

The Untold Truth Of Surfing Legend Duke Kahanamoku

If you have ever enjoyed the sport of surfing, whether you've gotten on the board yourself or watched in awe from the beach, then you have one man to thank. Duke Kahanamoku, today considered the father of modern surfing, helped not only to save the sport but pushed to make it a beloved worldwide pastime.

Kahanamoku was not just a surfer. He was also an Olympic-level swimmer who broke records for his time and earned three gold medals and two silver, according to the United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum. He appeared in over 24 Hollywood films. He once heroically saved people from a sinking ship. He traveled worldwide, not only spreading the love of surfing to people in places as far-flung as Australia and Jersey City but also winning lifelong friends and earning the love of others for his charm and love of the sport.

According to Britannica, Kahanamoku was born on Aug. 26, 1890, near what is now the ultra-popular tourist spot of Waikiki in Honolulu, Hawaii, on the island of Oahu. Until his passing in 1968, Kahanamoku was, for much of his life, not just a champion of surfing but a beloved figure and ambassador for Hawaii itself. Now, with surfing finally making its way to the Tokyo Olympics, Kahanamoku's dream of bringing his sport to an even wider audience is stronger than ever.

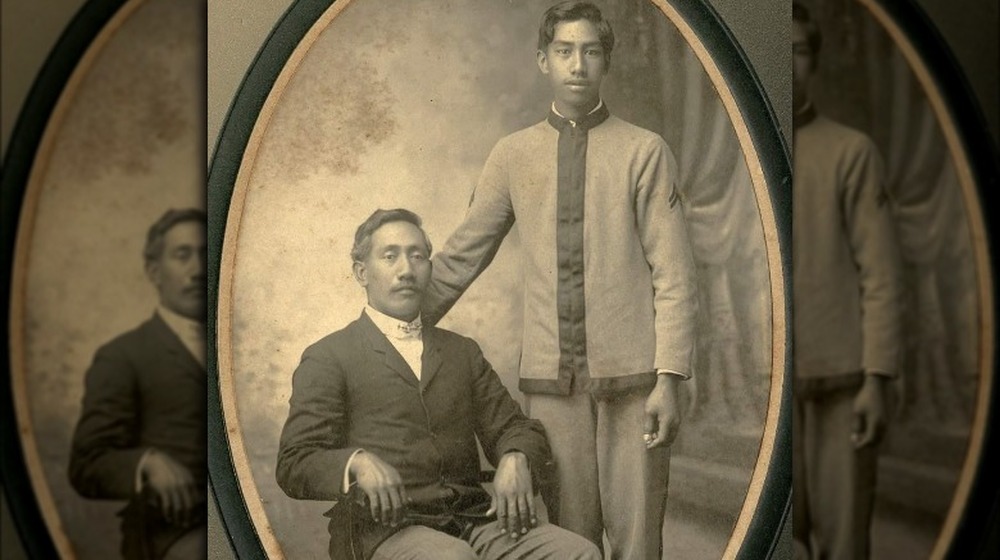

Duke Kahanamoku was named after a prince

Born to a family with a noble Hawaiian lineage, Duke Kahanamoku was already fairly unique at the time of his arrival. First, there's his name. According to Sports Illustrated, his given name really was Duke. He was named after his father, who was also named Duke after Prince Albert, the Duke of Edinburgh, visited the Hawaiian Islands in 1869. Both his parents, including his mother, Julia Paakonia Lonokahikini Paoa, were native Hawaiians who could claim noble blood from their ancestor, King Kamehameha.

Along with three sisters and five brothers, as well as many extended family members close by, Kahanamoku grew up in the family home in Waikiki. Nowadays, this area is a highly popular tourist spot in the capital of Honolulu, with packed beaches and a crowded surf. However, according to Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku, the Waikiki of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was nowhere near the hustle and bustle it witnesses today. Removed from the genuinely busy commercial center of Honolulu, Waikiki operated at a more leisurely pace. The people who lived there worked hard on making a living and tending to food crops like taro. They also made time for the beach, where Kahanamoku and other "beach boys" spent hours swimming and surfing in the Pacific Ocean.

Duke Kahanamoku helped save surfing from obscurity

Like other Hawaiian traditions, surfing was almost wiped out after the arrival of Protestant Christian missionaries. Hawaiian lifestyles changed dramatically with the arrival of these foreigners. While many people assume that the missionaries explicitly outlawed surfing, National Geographic reports that the matter was actually a bit more complicated. Rather than ban the practice, missionaries instead simply took up a lot of the Native Hawaiians' time.

Previously, Hawaiians' highly productive agriculture practices gave them plenty of time to spend at the beach and get really good at riding the waves. Settlers introduced things like capitalism and plantations that required near-constant labor. They also discouraged and intentionally suppressed many cultural practices. Even worse, newcomers introduced devastating diseases. According to Smithsonian Magazine, many Native Hawaiians simply did not have immunity to these illnesses and died in large numbers. Few were left to carry on with their lives, and fewer still were able to preserve all aspects of their culture and history.

By the time Duke Kahanamoku was born in 1890, surfing was very nearly lost. According to Sports Illustrated, his success as a swimmer in the first decades of the 20th century helped him bring more attention to his original love of surfing. For a significant part of his life, Kahanamoku toured around globe, demonstrating surfing to crowds in places like Australia, California, and Atlantic City. Without Kahanamoku's widespread renown, love for the sport, and awe-inspiring skill, surfing could very well have faded into the background.

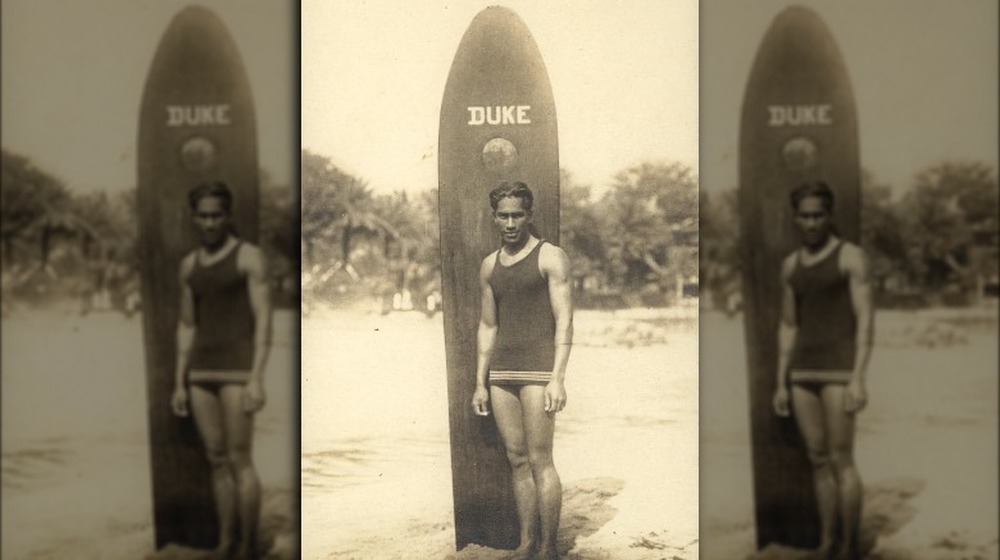

He loved traditional surfboards

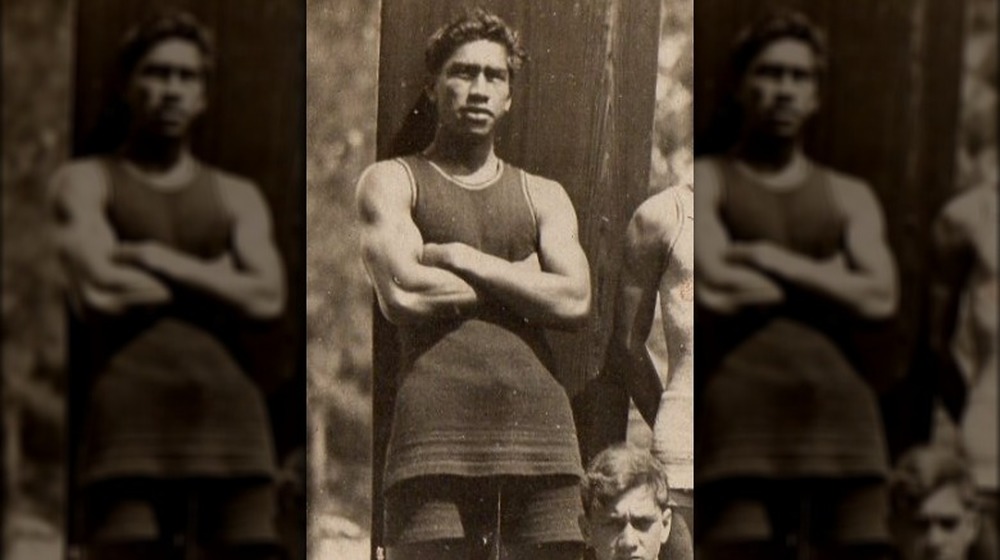

Historically, the Hawaiian kings and nobles who surfed did so on wooden boards. This was no easy feat, as the boards had to be handcrafted out of solid wood, making them heavy and difficult to pilot through the waves. Duke Kahanamoku, like his ancestors, preferred this old style throughout his career, even when lighter boards made out of synthetic materials became available.

Throughout his life as a surfer, Kahanamoku even made his own boards. Men's Journal reports that Kahanamoku preferred ones made out of native Koa wood, often coming in at over 10 feet tall and weighing in excess of 100 pounds. He also typically rode without a stabilizing fin on the bottom, now a common feature on modern boards. The Smithsonian National Museum of American History holds a similar board in its collections, made by Kahanamoku out of redwood while he was at Corona del Mar, Calif., in 1928.

For Kahanamoku, who stood over 6 feet tall and was a powerful swimmer, managing this style of board wasn't much of a problem. Though he would eventually try some of the newer styles, he reportedly always returned to the classical surf boards that recalled Hawaiian history. Even at age 40, Waterman states that Kahanamoku wanted a truly monumental ride that 10-foot surfboards couldn't give him. In the 1930s, he had moved back to Hawaii after a Hollywood career. Wanting to return to surfing, he carved his own 16-foot board that weighed over 100 pounds.

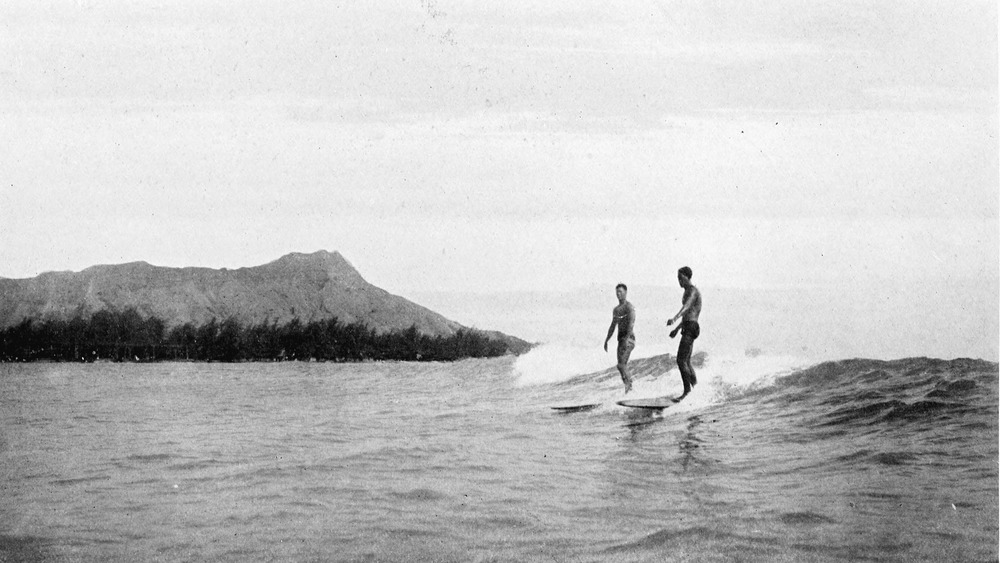

Duke Kahanamoku once surfed a legendary wave

By the time 1917 rolled around, the young Duke Kahanamoku had already become an established "beach boy," swimming and surfing around the coasts of Hawaii. He was already primed to become a legend of the sport and Hawaiian history, but a fateful wave cemented his status as surfer extraordinaire.

According to the Christian Science Monitor, that wave arrived in an area far out from Waikiki, in an area already known for its good surfing. The spot was sufficiently far out that many called the area "Steamer Lane" because it was close to the busy shipping route in and out of Honolulu.

Men's Journal reports that a storm near New Zealand had created a large wave that rolled across the Pacific Ocean towards Oahu, hitting it from the south. Kahanamoku later guessed that the wave was somewhere around 30 feet tall at its height. Waiting in Steamer Lane with his surfboard, he picked it up and began surfing for what became a celebrated ride. The massive wave took him more than a mile along the coast, until it ended around Canoes, an area where beach boys gave tourists rides in outrigger canoes. Kahanamoku's ride, made on a traditional wood board that weighed more than 100 pounds, made practically everyone take notice. Since the waves on the south shore of Oahu don't break in the same way that they did back in 1917, no one's been able to replicate his feat since.

Duke Kahanamoku was a record-breaking swimmer

Like many of the other beach boys who spent their time at Waikiki, Duke Kahanamoku was also an exceptional swimmer. He proved this to the larger world at the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) meet held in Hawaii in 1911 where, according to Sports Illustrated, he smashed the 100-yards world record. AAU officials refused to believe in Kahanamoku's accomplishment, first saying that something must be wrong with the timekeeping then arguing that he had been helped along by ocean currents.

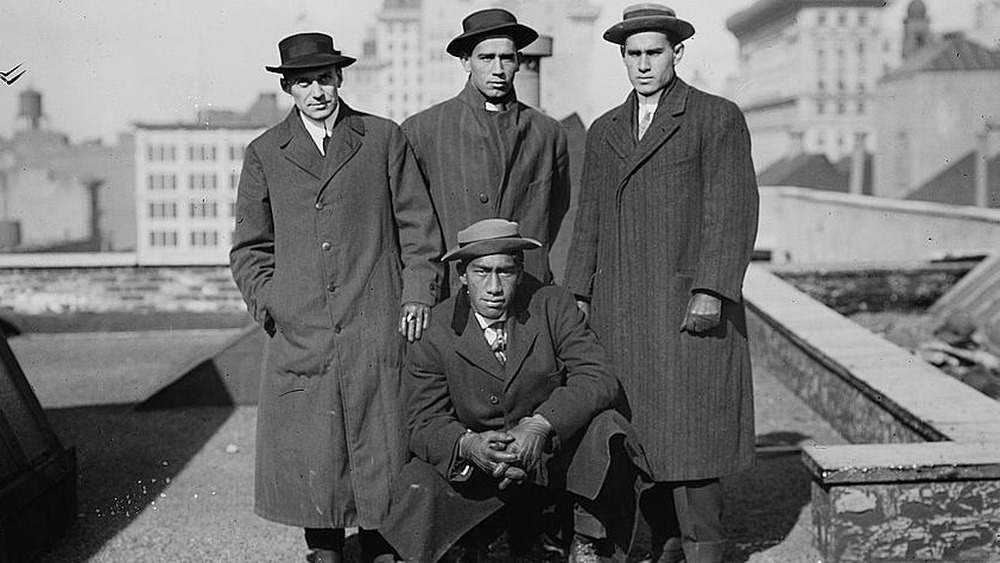

Locals knew Kahanamoku was the real deal, however. To prove it, they raised money to send him to the Olympic trials in Philadelphia. Kahanamoku won the 100-meter freestyle there and secured his spot as the top qualifier for the 200-meter relay. As per the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum, his swimming at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics earned Kahanamoku a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle and a silver in the 200-meter relay. In 1920, according to the Olympic Games, he won gold in both events at the Antwerp Olympics, where he also handily defeated world records. At the 1924 Paris Olympics, he also took home the silver in the 100-meter freestyle. By that time, it was clear to everyone that Kahanamoku was as much a master swimmer as he was a celebrated surfer. He had even introduced a new style of swimming that combined a flutter kick and powerful arm strokes, bringing him all the more closer to Olympic legend.

Duke Kahanamoku made Australia wild for surfing

Today, Australia is considered to be something of a surfer's paradise, with many miles of coasts, great waves, and an enthusiastic surfing community. For many, that's all thanks to Duke Kahanamoku.

After his successes at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, Kahanamoku's name started to gain worldwide recognition. When it came to Australia, Kahanamoku also wanted to pay back a kindness given to him at the games, says The Sydney Morning Herald. Back in Stockholm, the U.S. swimming team had confused the time for the finals, missing the event. It could have been a disaster for the U.S., but Cecil Healy, an Australian swimmer, was part of a group that argued for a re-do. The U.S. participated in a new heat, where Kahanamoku and his teammates won gold. He soon became friends with Healy. In 1914, he arrived in his buddy's native Australia to put on a few swimming and surfing exhibitions.

Australians were fascinated by Kahanamoku, The Guardian reports. He was already a famous swimmer and, by many accounts, was a very handsome and charismatic man who knew how to draw a crowd. His surfing exhibition at Sydney's Freshwater Beach took place on Jan. 10, 1915, and was attended by about 400 people. Kahanamoku wowed them as he rode waves and did tricks on his handcrafted board. Many today credit this and Kahanamoku's other surfing demonstrations as the events that kicked off the surfing craze that still has a hold on Australia today.

He became an unofficial ambassador for Hawaii

For many celebrities and officials who visited the islands in the 1920s and 1930s, going on an outrigger canoe piloted by Duke Kahanamoku was de rigueur. Now well into his 30s, the still-surfing Kahanamoku became "beach boy emeritus," in the words of Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku. That was a bigger job than one might expect, as unofficial as it was. Hawaii was quickly becoming both a popular tourist destination and somewhere people wanted to settle. From a 1910 population of 192,000, the number of people living in the Hawaiian Islands had nearly doubled by 1930. Even an unofficial ambassador like Kahanamoku had a full plate.

Said plate included entertaining such big names as Charlie Chaplin, Groucho Marx, aviator Amelia Earhart, baseball great Babe Ruth, and child actor Shirley Temple. Sports Illustrated reports that he also met with President John F. Kennedy and taught the hula to the late Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. Many of these visitors went on rides in the waves with Kahanamoku, either on his surfboard or on a somewhat more stable outrigger canoe. Kahanamoku also wasn't above playing a game of golf with visitors on the first courses on Oahu. Later on, he was also officially paid for many of these duties by Hawaii.

Duke Kahanamoku had to be very careful about getting paid

Being an Olympic athlete had a complicated side, as Duke Kahanamoku would learn. The Olympians reports that this lesson came at the expense of his friend and fellow American, Jim Thorpe. The Olympic Committee had revoked Thorpe's 1912 Olympic medals after they learned that he had played semi-pro baseball for a year. Because he had been paid, Thorpe was no longer considered an amateur, a key requirement to compete in the Olympics.

That presented a real issue for Kahanamoku. With the 1916 games cancelled due to World War I, he had to remain an amateur for eight years until the 1920 Olympic Games. How was he supposed to live in the meantime? Moreover, how was he going to keep bringing positive attention to Hawaii if he got into a financial scandal and lost his medals? Ultimately, a trust was set up to purchase a home for Kahanamoku, so he at least had a roof over his head. Still, he had to contend with other complexities.

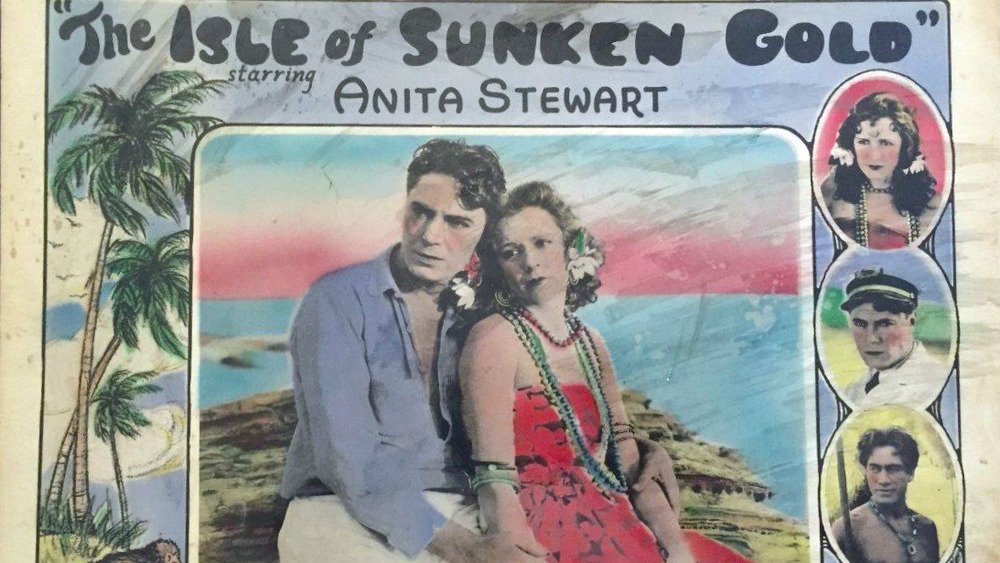

That enforced amateur status also impacted his burgeoning film career. Waterman reports that The Beachcomber, a film made soon after the 1912 Olympics, was a casualty of the situation. The silent film, shot in southern California, starred Kahanamoku as an islander who saves a damsel from drowning. Sounds interesting, but U.S. audiences never saw it. Director Hobart Bosworth declined to release The Beachcomber there, for fear that it would impact Kahanamoku's amateur athlete status.

He heroically rescued people from a sinking ship

In June 1925, while he was on the beach Corona del Mar, Calif., Duke Kahanamoku saw a disaster unfolding in front of him. According to The Olympians, he saw a boat, the Thelma, in the choppy waters just off the beach. The ship's captain had failed to acknowledge the checkered flag flying in the harbor, which meant that the waters that morning were unsafe. The winds and waves began to intensify, to the point where the Thelma began to list at a dramatic angle in waves as high as 20 feet. It was clear that the passengers and crew of the boat were in great danger.

The L.A. Times reports that Kahanamoku quickly swam out on his surfboard and began to rescue people from the sinking ship. Witnesses reported that he was the first to respond, though other surfers began to help in the rescue effort. He gathered up to three people on his 12-foot surfboard at a time, ferrying them back to the shallows and to safety. All told, 12 people out of the 17 on board were rescued by surfers on the shore. Kahanamoku personally saved eight people.

Duke Kahanamoku tried for a film career but ran up against serious obstacles

After his athletic successes in the 1910s and 1920s, Duke Kahanamoku moved to California to begin his pursuit of a film career. Though, as The New York Times reports, he starred in over two dozen movies, he was often relegated to side roles. Kahanamoku was typically enlisted to play "exotic" figures like Native Americans, pirates, South Asians, and Pacific Islanders.

It was a disappointment for Kahanamoku, who had hoped to win starring roles instead of bit parts. After all, hadn't he gained worldwide fame as an Olympic swimmer and masterful surfer? Didn't people flock to see him demonstrate that skill? Why couldn't that translate to the screen?

Waterman argues that his considerable acclaim could only get him so far in the closed off world of Hollywood. Kahanamoku also had to contend with deeply racist attitudes that often left him out in the cold. It's worth remembering that, as Surfline reports, Kahanamoku was a Native Hawaiian with dark skin. Ultimately, this meant that many dismissed his abilities or else indulged in exoticism that downplayed his skill and relegated him to background and supporting roles. This discrimination dominated his film career, meaning that he never really got a coveted lead role, as earlier industry people had promised him. By the 1930s, Kahanamoku had more or less given up on the goal of becoming a movie star and had moved back to Hawaii.

Duke Kahanamoku literally laid down the law in Honolulu

Though he still loved to surf by the time he returned to Hawaii after the 1932 Olympics, Duke Kahanamoku had to figure out how to make a living after his athletic career had begun to slow down. The Honolulu Star Advertiser reports that he was at a bit of a loose end when the head of Union Oil in Hawaii asked the surfer if he'd like a job. "I said heck yes," Kahanamoku later reported. "I'm not too proud to pump gas."

Thanks to this encounter and his own willingness to work the job, Kahanamoku ran two Union Oil gas stations on Oahu for a short time. By 1934, however, he had found a new career. By then, Kahanamoku had decided to run for sheriff of Honolulu, an office he won and attained in 1935. The Hawaii Democrat reported that he was a popular figure, easily winning reelection in 1936. He would go on to serve a total of 13 terms until 1960, when the office was shuttered, according to Hawaii.com. Afterward, he worked as Hawaii's official welcome ambassador, a paid role that helped him establish an even more stable life in the islands.

Duke Kahanamoku's legacy continues to this day

Though he died of a heart attack in 1968, Duke Kahanamoku's legacy remains strong today. One of his greatest impacts, and one that he would surely be happy to see, is the inclusion of surfing as a debut sport at the Tokyo Olympics, to be held in 2021. Swimming World reports that Kahanamoku had dreamed of competing as an Olympic surfer as well as a swimmer. If it had been accepted as an official Olympic sport during his heyday at the games, he would have certainly won more than his already impressive total of five medals.

Surfers now competing at the Olympics and on other world stages owe a lot to Kahanamoku for his work bringing the sport back from the past and into the mainstream. If they want to pay their respects, they can visit one of a few statues worldwide, including a monument installed at Sydney's Freshwater Beach after his highly successful stint around Australia in surfing and swimming exhibitions. If they're in Honolulu, they can visit yet another statue of him at Kuhio Beach, says The Hawaiian Islands, not too far from his original home of Waikiki.