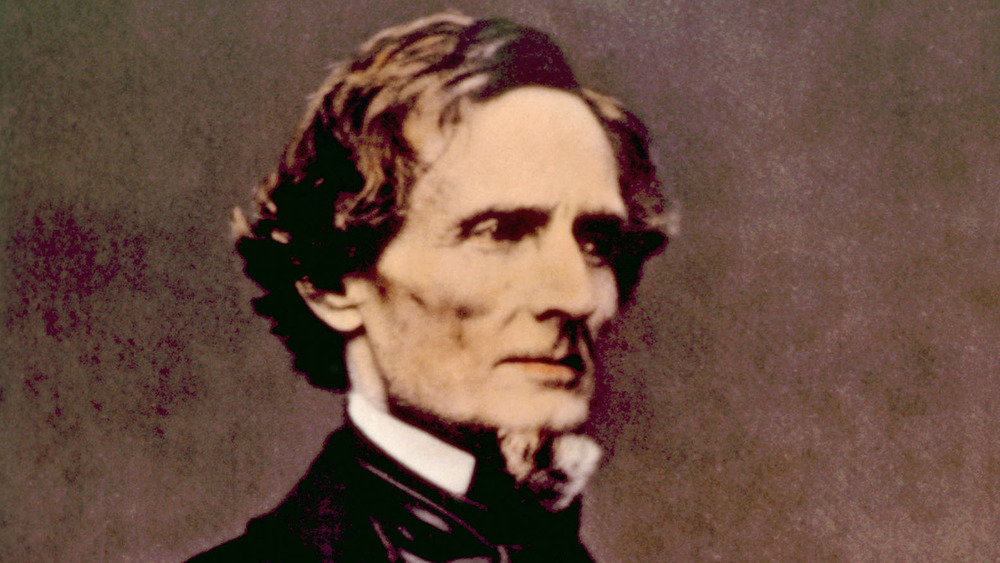

What Happened To Jefferson Davis, President Of The Confederacy?

Although Jefferson Davis had a celebrated military career, served as a U.S. senator and as the secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States, his legacy, as Biography reports, is tarnished by his tenure as president of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War and his subsequent indictment for treason.

Davis, one of 10 children in a military family, grew up mostly in Mississippi during the early 1800s before attending boarding school in his Kentucky, the state of his birth. He attended Jefferson College in Mississippi and Transylvania University in Kentucky before graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York, according to Britannica. A bit of a mischief-maker, Davis and other cadets got into trouble smuggling liquor into their quarters for an early morning holiday party. When discovered, the group were confined to their rooms. The Times-Picayune writes that Davis behaved himself, but his companions broke windows and fought their superiors in a drunken bout now called the Eggnog Riot and were expelled.

He stayed in the military, fighting in the Blackhawk War in 1831. In 1833, he became a first lieutenant in the newly formed regiment, the First Dragoons. He left the service in 1835 after marrying his commanding officer's daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor, despite opposition from her father, the future president Zachary Taylor. Unfortunately, Sarah died of malaria a few months later.

Jefferson Davis and his presidency

Davis entered business as a cotton farmer and prepped for a political career. He served as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention in 1843 and his well-received speeches spurred opportunities. By December 1845, Davis was a member of Congress and remarried, to Varina Howell. "As a congressman, Davis was known for his passionate and charismatic speeches," according to Biography. He helped transition forts to military training schools and supported states' rights.

He left politics to fight in the Mexican-American War as a colonel under his former father-in-law. In the Battle of Buena Vista he fought so valiantly that even Taylor had to admit that he had misjudged Davis all those years ago. In 1847, Davis was appointed U.S. senator from Mississippi, serving from December to January, and then elected to the office for another term.

From 1853-1857, Davis served as secretary of war, and then returned to the Senate. He resigned when Mississippi seceded in January 1861, becoming president of the Confederacy in February 1861. The decision didn't turn out well for Davis. According to History, "Davis worked very hard at his presidential duties, concentrating on military strategy but neglecting domestic politics, which hurt him in the long run." Lacking charisma, Davis often relied on the wrong people, like General Braxton Bragg, who was defeated by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the battle at Chattanooga.

Davis and his later life

He was captured in May 1865 and charged with treason. Rumors said that Davis was wearing his wife's clothes at the time, but according to Warfare History Network, "Whether he grabbed his wife's cloak in his haste, or she threw it over him as a cover, depends on who tells the tale." Northern newspapers capitalized on Davis's predicament with headlines like "Jeff Davis Captured in Hoop Skirts."

He was imprisoned at Virginia's Fort Monroe from 1865-1867. "In prison his physical and emotional health deteriorated, and he was never the same after he was released in May 1867," reported Warfare History. His case never went to trial.

Later in life Davis traveled overseas, became president of a life insurance company, and wrote a book, "The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government," to explain his political beliefs. He died in 1889 of acute bronchitis. But he was not forgotten. Some Southern states still celebrate his birthday, and a presidential library opened for him in 1998. Still, many public monuments of him have become controversial, such as one in a Memphis, Tennessee park that was taken down in 2017. As The Tennessean explains, some historical figures "are ever-present reminders of racial discrimination and violent oppression that has never gone away."

Ultimately, many historians view Davis's leadership legacy as a failure, largely because of his quick temper, "an inability to navigate politics, and a willingness to reward friendship over competence," according to The Times-Picayune.