The Mysterious Organization Behind The Escape Of Nazi War Criminals

While it might seem pretty straightforward that after the end of World War II, the Nazi party — and those who touted their deadly ideals — needed to pay the price for their crimes, it didn't exactly work that way. According to Mary Fulbrook, a University College London professor of German history (via CNN), "The vast majority of perpetrators got away with it."

Fulbrook estimates that there were around 200,000 people responsible for carrying out the crimes of the Third Reich and says that between 1945 and 2005, about 140,000 saw their day in court. Shockingly, only 6,656 of those cases ended with a conviction.

The problem was linking those on trial to specific killings, and it wasn't until the trial of John Demjanjuk in 2011 that a precedent was set — prosecutors could now go after lower-ranking officials and didn't need to prove they had killed Person A, B, and C, just that they had been involved in the whole thing.

But there was something else going on here, too. Many Nazi war criminals fled Europe in the aftermath of the war and ended up in South America. How they got there is equal parts bizarre and terrifying, and it shows that things didn't end with the last shot fired.

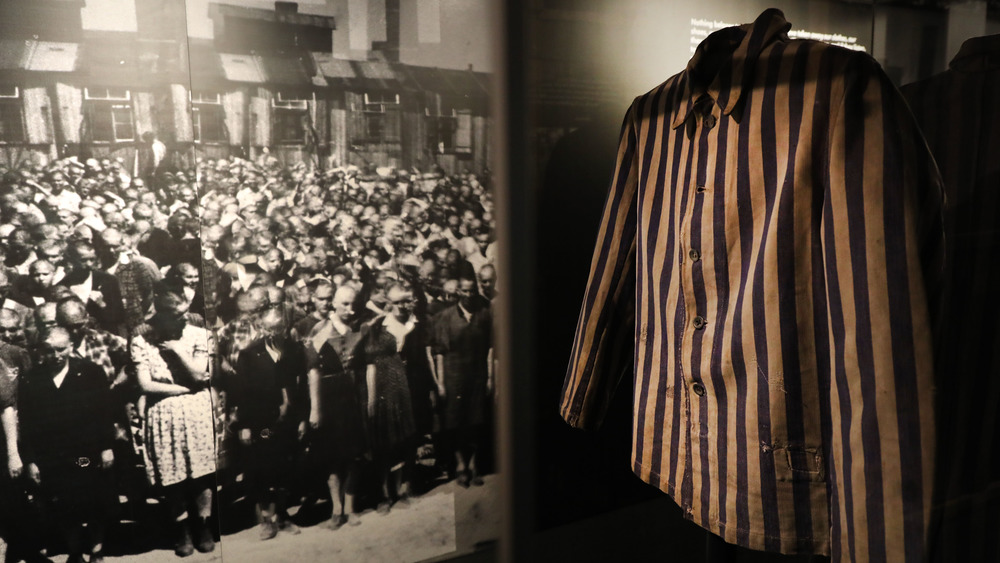

The sheer scale of the Nazi exodus to South America is staggering

In the final days of World War II, Allied forces scrambled to save those they could and bring others to justice. At the same time, a staggering number of Nazis fled Europe before that justice could come for them.

According to Aish, there were fewer than 300 Nazis put on trial at Nuremberg (like Joachim von Ribbentrop, pictured, who was given a death sentence). By comparison, around 9,000 headed to South America. It's estimated between 1,500 and 2,000 ended up in Brazil, between 500 and 1,000 went to Chile, and Argentina opened their doors to shelter as many as 5,000.

It's not entirely surprising. Before the war, Brazil was home to the largest number of Nazis outside of Germany, and Argentina's Juan Peron was a huge fan of Adolf Hitler's policies and practices. South America was so welcoming of Nazi war criminals that a single Chilean town — Colonia Dignidad — was outed in 1962 as the home of 300 families who had fled Nazi Germany.

How they got there is complicated, and the network that facilitated their flight was so shrouded in secrecy that bits and pieces are still being uncovered by historians like Gisela Heidenreich. Her 2012 book, Beloved Criminal: A Diplomat in the Service of the Final Solution, put the spotlight on key components like a Mercedes-Benz factory outside Buenos Aires, which she says was instrumental in moving people and money.

The meeting that set up Odessa

Here's the claim — according to Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, it started when he was speaking with a former member of a German counter-espionage group during the Nuremberg trials. That, he says (via the Jewish Virtual Library), is when he learned of an organization called Odessa.

The story goes that on Aug. 10, 1944, a group of German bankers and industrialists held a meeting at Strasbourg's Maison Rouge hotel. The reason for the meeting was simple — things weren't looking great for Germany, and just in case the Allies won, they wanted a plan that would not only keep their top people free and clear but would set the groundwork for the transfer of their ill-gotten gains to somewhere out of Allied reach. The thinking was that with an escape plan in place, they would be able to regroup and rebuild the party somewhere else.

That organization, says Wiesenthal, was Odessa — otherwise known as the Organization of Former SS Members or Organization Der Ehemaligen SS-Angehorigen. Members of the original meeting started laying the groundwork for Nazi escapes to South America. They set up safe routes of passage, transferred funds, got falsified documents, and created this sprawling, underground network of contacts that would ensure the survival of the Third Reich. Or... did they?

No one's really sure just what (or if) Odessa was

This is where things get complicated, because historians can't agree on pretty much anything about Odessa.

On one hand, Simon Wiesenthal was convinced that there had to be a massive organization with deep pockets pulling the strings and getting Nazi party members — and their money — to safe countries (via the Jewish Virtual Library). But on the other hand, there's plenty of other historians who say (via Aish) that there was no such thing as Odessa, and there were no super secret meetings or organizations at all.

Then, there's other opinions that the truth is somewhere in the middle. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) says that yes, there was a network dedicated to helping Nazis — and particularly SS — escape Germany. They suggest that Odessa was just one part of that, and say other divisions had code names including Die Spinne, Skylark, Danube, and HIAG (the Mutual Aid Society of the Waffen SS).

They add that evidence of Odessa's existence is hard to come by because it was so top secret, and even memorandums from Allied intelligence were highly classified. Meanwhile, JTA also says that while most of these organizations simply ceased to exist by the late 1940s, there was at least one — Die Spinne — that was active throughout the 1950s. Some claim that it never went away, and that it's still up and running right through into the 21st century.

The Odessa File

If the story of Odessa sounds like something out of a novel, well, it was. Frederick Forsyth (pictured) was a Royal Air Force pilot and investigative journalist turned author, and among his list of bestsellers is The Odessa File. It's the story of a reporter who's investigating the suicide of a Holocaust survivor, and it soon turns into the story of Odessa and Nazi escape routes. Fiction? Or truth?

According to the Independent, Forsyth maintained that while some of the story was fiction, it was very much based in fact. He — and the newspaper — had seen some of the documents that United States intelligence had collected on an operation called Project Safehaven.

They also had testimony from the World Jewish Congress. Executive director Elan Steinberg confirmed, "The Odessa existed and they removed billions of dollars in looted Jewish assets from Germany. Their plan was to re-establish the Nazi Party from safe havens outside Germany, and many of the assets they smuggled out must still exist."

The documents in question came from a French intelligence agent who observed the 1944 meeting where the seeds of the plan were laid, and according to a 1945 telegram sent from the U.S. State Department, Odessa had somewhere around $123 million in gold bullion stored in Swiss banks. Truth? The Swiss banks in question have refused to open their archives, and Forsyth maintains he'd gotten word of Odessa from "friends in low places."

The ratlines

According to the BBC, the term "ratline" was coined by U.S. intelligence to refer to the network of contacts and safehouses used to ferry war criminals from Europe to South America. It was dangerous, but they also had a lot of help along the way.

Historian Bill Niven of Nottingham Trent University says (via History Today) that there were several ratlines that were the most frequently traveled. One was dubbed the Nordic route and went from Denmark up into Sweden and then on to Argentina. Another — the Iberian route — went through Spain, and still another was called the Vatican route. Like the name suggests, that one went through Italy, and the final jump was made either from Rome or Genoa.

Along the way were a series of safehouses where Nazis on the run could lie low for a while. And along the way, they also picked up falsified papers and passports that allowed them to not only escape Europe but start a new life under a new identity. Adolf Eichmann — the man who had been in charge of overseeing the implementation of the Final Solution — was one of those people. By the time he reached Argentina, he had become Ricardo Klement (via The Guardian).

Documents were supplied by the Red Cross

Way back in 1999, the BBC reported on how at least ten Nazi war criminals got their falsified documentation through the last organization that anyone might suspect — the Red Cross. The relief organization was linked to giving travel papers to some of the biggest names on the most-wanted list, including Josef Mengele, Adolf Eichmann, SS captain Erich Priebke, and the Gestapo's Klaus Barbie.

The Red Cross called it one of the "painful and regrettable experiences from the past," and said that it had supplied the paperwork without knowing who they were really giving it to.

Fast forward to 2011 and the research of Gerald Steinacher, a fellow at Harvard University. When he was given access to the Red Cross archives (via The Guardian), he found that there were many, many more documents that had been issued to Nazi war criminals that had helped them on their way. Instead of the original ten, he found numbers reaching into the thousands.

What happened, he says, was complicated. War criminals would mix with legitimate refugees and often pretend to be what he called "stateless ethnic Germans." Papers were issued "out of sympathy for individuals... political attitude, or simply because they were overburdened."

The Catholic Church and the Vatican were involved

When Franz Stangl was finally put on trial, it was for the murder of 900,000 people — to which the Jewish Virtual Library says he argued, "My conscience is clear. I was simply doing my duty." He was also one of the Nazis who escaped justice with help from the Vatican and the Catholic Church.

DW says that he escaped from jail in 1948 and headed to Rome, where the Bishop Alois Hudal was waiting. Also waiting for him were falsified documents that allowed him to go to Syria. From there, it was on to Brazil, where he settled down and got a job making Volkswagens.

As many as 90% of the Nazis who fled Europe have been estimated to have gone along a ratline that led through a monastery of the Teutonic Order, a Capuchin monastery, and right into Rome, where the Catholic Church would give them identifying papers, which would then be presented to the Red Cross for travel papers.

Hudal, says The Telegraph, was incredibly open about his pro-Nazi stance, and he even sent correspondence to Adolf Hitler approving of things like the annexation of Austria. He later went on to say that those he helped were "completely blameless," and according to Friedrich Schiller University professor Daniel Stahl, escaping Allied justice "would have been much more difficult" without the protection of the church. The Catholic News Agency derides the claims as "verifiably false."

Nazi gold crossed the Atlantic, too

According to an Argentine documentary called Nazi Gold in Argentina (via the Independent), millions of pounds of Nazi gold made its way to South America via submarine near the end of the war. Interviews with Nazi survivors, evidence collected from a U-boat museum in the Baltic, and files from the archives of British intelligence allowed historians to piece together the story of how Juan Peron and his paymaster, Rodolfo Freude, not only helped Nazis make the jump to relative safety in South America, but how they also oversaw the transport of an insane amount of financial assets.

Peron isn't the only one who had a hand in bankrolling the escape of Nazi war criminals. According to The Jerusalem Post, Argentine investigators uncovered a long list of names in 2020. The list — which was given to the Simon Wiesenthal Center — was found in storage in the former headquarters of the Nazi party in Buenos Aires. It contained 12,000 names of Argentina-based Nazis who had accounts in the Credit Suisse bank in Zurich, Switzerland. It's not the first connection that's been made between Nazis and Swiss banks — over the years, others have been named as having facilitated the transfer of Nazi funds and gold from Europe into South America.

PBS says that at the end of the war, the Allies recovered only about 12% of the gold stolen by the Nazis.

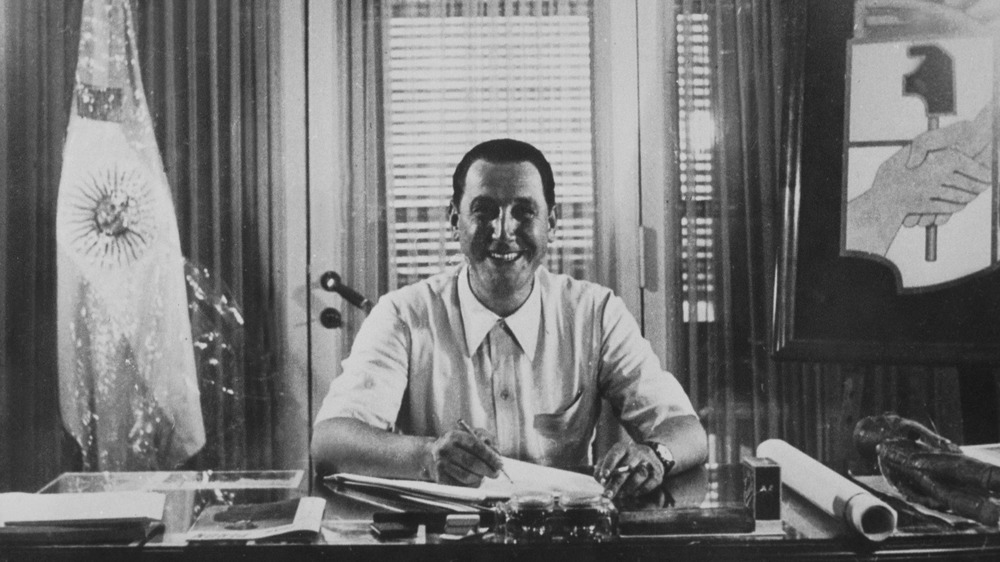

Juan Peron and his open door

Even before the end of the war, Argentina's Juan Peron (pictured) was making it very clear that his country was going to be a safe haven for any Nazi who wanted it... should things go badly for Germany. In 1944, the Wilson Center says the Argentine embassy in Lisbon was accused of selling passports to German citizens, even as the Spanish government went out of their way to make sure there were designated stopover points for flights from Germany going to Argentina.

Given the past relationship between Peron, Argentina, and the countries that made up the Axis powers, that wasn't entirely surprising. ThoughtCo. says that before and during the war, Argentina maintained a close relationship with the Axis — and only joined the Allied cause a month before the end of the war. Even then, Peron had already made it clear that the move was just to appease the U.S.

They also say that Peron went out of his way to make sure his Nazi friends had all the help they needed, going as far as sending representatives to Switzerland, Spain, and Italy to help supply Nazi fugitives with papers and money. They made travel arrangements, promised jobs and a place to stay once in Argentina, and no one was refused. Why Peron was so enamored with the Nazis is complicated — part of the reason was pure anti-Semitism.

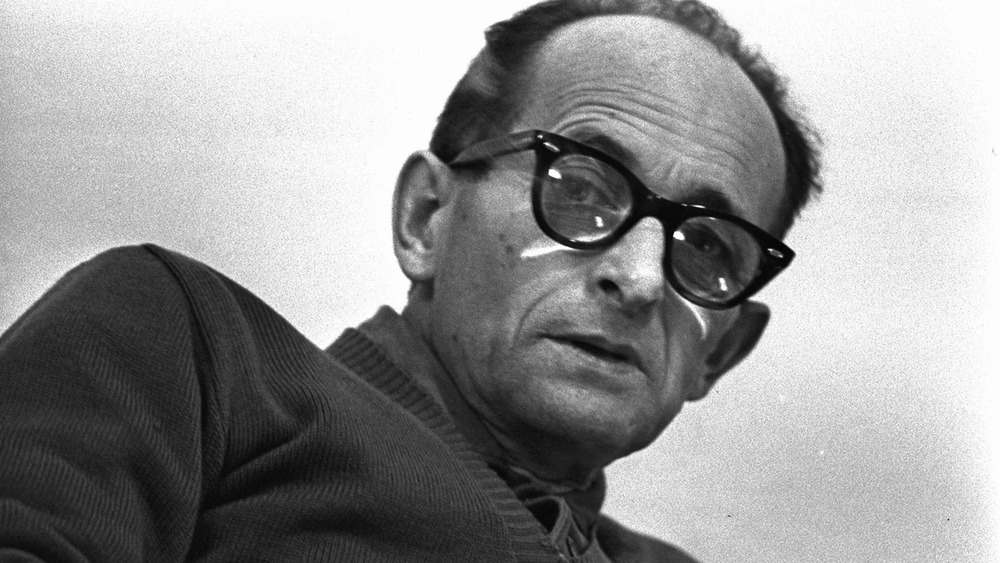

Who escaped to South America?

It wasn't just low-ranking grunts and guards who slipped through the ratlines to South America — there were some pretty big names who made their way to freedom with the help of Nazi sympathizers (via History).

Some were ultimately brought to justice. Final Solution architect Adolf Eichmann (pictured) entered Buenos Aires in 1950, was snatched by Mossad agents in 1960, taken to Israel, tried, and handed the death sentence. Franz Stangl — nicknamed White Death — went to Brazil in 1951 and was arrested in 1967. He spent the rest of his life in jail. And SS commandant Josef Schwammberger didn't even bother with an alias after he settled in Argentina in 1948. He was even given citizenship and was only returned to Germany in 1990, where he was put on trial and given a life sentence.

Others were never caught. Walter Rauff, the designer of the mobile gas chamber, went first to Ecuador then Chile, where he worked at a king crab cannery. When he died in 1984, mourners gathered to give Nazi salutes at his graveside. And the most infamous of all? Josef Mengele, the so-called Angel of Death. He went through Italy to get to Argentina and spent time living in Uruguay, Brazil, and Paraguay. In 1979, he had a stroke while swimming off the coast of Brazil and drowned.

The Butcher of Lyon, the ratlines, and the U.S. Army

At least one Nazi war criminal — Klaus Barbie (pictured), the so-called Butcher of Lyon — was aided in his escape by a massive yet sill mysterious organization — the U.S. Army. According to The National WWII Museum, Barbie was the worst of the worst, famous within the Gestapo and the SS for his brutality.

At the end of the war, Barbie suddenly found himself employed by the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Corps (CIC). After spending four years working as an agent for the CIC — and being protected from the French government, who wanted to put him on trial for war crimes — Barbie was transferred to a program run by the CIC's Austrian division. It was called Operation Ratline, and according to The Washington Post, it was meant for use by Soviet defectors and informants, along with Croatian nationalists. Barbie was, it seems, the only Nazi to travel that route.

Ratline kicked off in 1947, and it was overseen by a Croatian priest and seminary teacher stationed in Rome. His name was Krunaslow Draganovic, and he knew exactly who to bribe to get people where they paid him to be taken. For Barbie, that was Bolivia.

And there, the Jewish Virtual Library says, he lived as Klaus Altmann from 1951 until his eventual extradition in 1983. He was put on trial in France, sentenced to life in prison in 1987, and died four years later of leukemia.

Operation Paperclip

Not all Nazis escaped to South America. Some were taken to the U.S. and given jobs in the top of their respective fields.

In a nutshell, this is what happened (via History) — at the end of the war, U.S. forces started scrambling for any new technology they could find and quickly realized that in addition to taking the actual tech back home, they could take the minds who created it, too.

The result was Operation Paperclip, and by the end, around 1,600 German scientists — and their families — were relocated to the U.S. At the same time, President Harry Truman made it very clear that under no circumstances were Nazi party members to be hired by U.S. organizations. Those behind Operation Paperclip — including the OSS, precursor to the CIA — got around that ruling by simply destroying any evidence that these new German scientists had in fact been Nazis.

The most high-profile of these is probably Wernher von Braun (pictured), who got his start in rocket science by designing weapons for the Third Reich. More than 3,000 of his rockets were launched against the Allies, says Time, and around 20,000 prisoners of forced labor camps died while building them. After he was transferred to the U.S. side of things, he went on to become the face of the space program, develop the country's first ballistic missile, and be the poster child for the cool, suave engineer that got the nation to the moon.