Planet Earth Is Even More Bizarre Than You Thought

Science has come a long way in the last few centuries. We've learned a whole lot about Planet Earth, and honestly, what we learn just keeps getting weirder and weirder. For every question that science manages to answer, we discover something else that reminds us how just unlikely and strange Earth truly is.

The planet's core contains a shocking amount of gold

Gold is valuable stuff, and there's no denying the world's economy revolves around this super-precious substance. While it's weird to think we're basing everything on our love for shiny rocks, it's even more bizarre to think of how much gold is contained in the planet's core.

If you were somehow able to extract all the gold from the planet's molten core, you could cover the surface of the Earth in a layer nearly a foot-and-a-half deep. That's a ridiculous amount of gold, and scientists have estimated that it works out to roughly 1.6 quadrillion tons. Do you have any idea how much candy you could buy with that much gold?

Those same scientists also figured out that it was only a freak accident that allowed us to discover any gold on or near the surface in the first place. It took somewhere between 30-40 million years for Earth to go through the process of becoming the solid rock we know and love today. While it was still a molten lump of space goo, all the metals that are attracted to iron (like gold) were drawn into the core. Around 200 million years after the planet solidified, there was a massive extraterrestrial shower that pummeled the planet and added gold and other precious metals to the surface. That's the relatively tiny bit we've found, while most of our own gold supply remains tantalizingly out of reach.

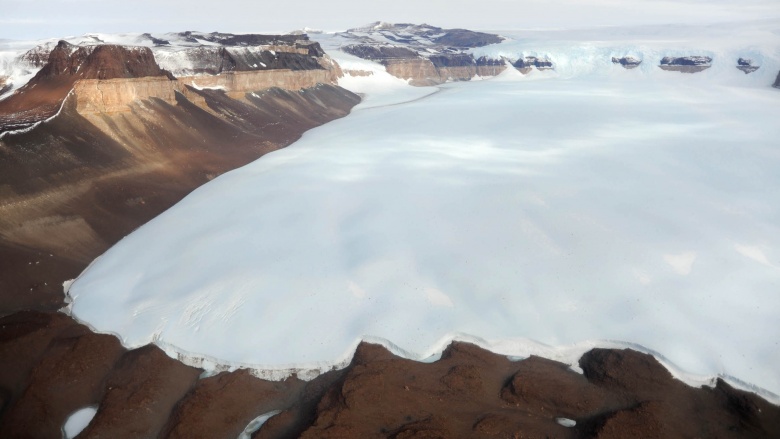

The world's driest desert is in ... Antarctica

Quick, name the driest desert in the world. The Sahara? Death Valley? Not quite. Since you probably already read the title to this entry, you now know that it's in Antarctica. The area is called the Dry Valleys (that's no misnomer — no precipitation has fallen there in at least 2 million years), and while most of the continent is covered by ice that's up to two-and-a-half miles thick, these valleys (which total around 4,000 square kilometers) are completely bare.

The rock was exposed around 12 million years ago, when a subglacial flood broke loose and carved the valleys out of solid rock with a force roughly about the same as 13 times what flows through the Amazon River. Winds averaging around 200 mph have eroded the exposed rock into a wild landscape of outcroppings and valleys, and over the years they've sorted the rocks and rubble into bizarre formations. Those wind-blown rocks are only a small layer, though, and in places they hide rivers of ice that haven't budged in millions of years.

They're not the only strange things you'll find there, either. Even though the temperature almost never gets above freezing, there is the occasional pond of water so salty, it doesn't freeze. The odd animal does, though, and some particularly disturbing photos show corpses so dry, they've completely mummified.

The bacteria that can breathe uranium

Bacteria are the building blocks of Earth life and, admittedly, it's easier to see that in certain people. The planet is literally covered in the little things, and we're far from knowing everything there is to know about bacteria. Science keeps discovering more and more about them, and one of the strangest kinds yet is a betaproteobacteria that lives around a mile-and-a-half underground, and feeds on uranium.

First discovered in an old uranium mine in Colorado, this strain of bacteria somehow absorbs an electron from uranium molecules, and essentially uses it to feed or breathe off of. That's a pretty big deal, too, because uranium that's been exposed to the bacteria is rendered inert. It no longer bonds with anything else, including groundwater, and that means it might be ideal for cleaning up entire sites contaminated with radioactivity.

Even weirder are the implications, including the idea that life can exist well beyond the limits of what we previously believed. If there's bacteria that can live off uranium, it's entirely possible that bacteria can live in extraterrestrial environments, too.

Icebergs make a sound called bergy seltzer

Icebergs are really weird things, and if you've only ever thought about them when watching Titanic, that's a shame. It might be a given that icebergs float for the same reason the ice in your glass floats, but there's more to it than that. Icebergs are formed when massive pieces of freshwater ice break off of glaciers. And, as the icebergs start to melt, they do a few weird things.

The melting freshwater throws off minerals and organisms that have been trapped in the ice for thousands of years. Get close enough, and you'll hear a crackling noise as each tiny, tiny air bubble bursts and releases ancient air. It's called bergy selzter, because it's a surprisingly loud noise that absolutely sounds like a freshly poured carbonated drink. (Check out the video, and make sure your sound is turned up.) Presumably, it was also named in the same spirit that gave us Boaty McBoatface.

Time is not a constant

A day is the length of time it takes for Earth to spin on its axis, and a year is the time it takes us to trundle our way around the Sun. We all know that, but the weird part is how much that absolutely has not been a constant.

An incredibly exacting amount of scientific research has found that the pressure from the ocean's tides is slowing the rotation of the earth by 1.7 milliseconds every century. Don't laugh — that's not just an amazing display of precision mathematics, it also means that Earth time is changing constantly, albeit minutely.

The force that's causing it is the same force that makes the planet bulge a bit around the equator, and it also implies the way Earth rotates and revolves hasn't always been the same. That's exactly what scientists found when they took a look at the growth of millions of years' worth of corals. Since corals form tree-like rings that document the day and night cycle, they were able to look at the length of a year from 350 million years ago. They learned that back then, it took us 385 days to make our trip around the sun, and at the same time, a day was slightly less than 23 hours long.

Go back to 620 million years ago, and you'd have been living through a 21.9-hour day and a 400-day year, which is way too long to wait for Christmas. On the plus side, that trend is continuing. Days are getting longer as the Earth continues to slow, and years are getting shorter as ... wait. That's not a good thing. In around 50 billion years, a day will be around 1,000 hours, or how long you feel your workday lasts. And a year? That's irrelevant, as the Sun would have gone Red Giant tens of billions of years before then. So, no worries.

Lakes can explode

It's called a limnic eruption, and it's only happened twice in recorded history. Particularly deep lakes can dissolve and capture a huge amount of carbon dioxide. When a nearby trigger occurs, like an earthquake, it can result in a massive explosion, ripping through the lake waters and spitting carbon dioxide into the air. Since CO2 is heavier than oxygen, that can cause major problems for everyone in the area.

It's not just a theory — it actually happened at Cameroon's Lake Nyos on August 21, 1986. When the lake exploded, it killed 1,746 people and 3,500 livestock animals in a single night, most of whom suffocated in their sleep. Those that were awake told a terrifying story of trying to save loved ones that were already dead. The explosion reached 300 feet into the air, sent a 60 mph shockwave of carbon dioxide across the entire area, and killed people from 15 miles away. There were 800 people living on the shores of the lake, and only six survived the night. Those that did survive were subject to CO2-induced comas, skin lesions, and survivor's' guilt.

Rwanda's Lake Kivu undergoes a limnic explosion on an average of every 1,000 years or so and, right now, it's overdue. The explosion would be catastrophic, and would impact an estimated two million people living in the blast zone. And Lake Monuon, also in Cameroon, is another so-called killer lake.

Rivers can boil

It sounds like something out of a book of legends and, originally, that's exactly what stories of boiling rivers were. According to South American myth, Spanish conquistadors looking for a lost city of gold ventured into the Amazon rainforest — the few that made their way out again told others about some pretty crazy things. One of those things was a river that boiled, so hot that it cooked and killed any living thing that fell into it.

Crazy, right? Well, it's real, and Andres Ruzo only discovered it hundreds and hundreds of years later. As a geophysicist, he became interested in the possibility that the river his grandfather used to tell him stories about was real, heated by the planet's internal processes, much like hot springs or a volcano. He found it, a 5.5-mile-long stretch of river in the Peruvian Amazon that, especially during the dry season, is hot enough to kill. Local shamans consider it a sacred place with healing abilities, though we're not sure we'd consider being boiled to death good for healing anything.

The scientific explanation absolutely doesn't make it any less of a mythological wonder. Ruzo found it was a naturally-occurring phenomenon, a non-volcanic patch of rainforest that just happened to be fed with geothermal energy at an insanely high concentration. While most of the river is hot, the temperature fluctuates, and only a relatively small portion boils. It still makes us wonder, though: how many more once-mythological mysteries are still waiting for modern science to uncover?

The instability of the planet's magnetic field

We like to think that there's at least some constants in this world, like the concepts of North and South. Unfortunately, they're not nearly as constant as we'd like to think.

On a geological scale, it turns out that pole reversal happens pretty frequently, thanks to that molten layer of the Earth's core. The sloshing around of all the liquidy bits means the iron content shifts enough that our poles shift with it. And it happens a fair bit, too. Around 800,000 years ago, south was north and north was south, and before that, the poles flipped every 200,000 to 300,000 years. That means we're way, way overdue for a little pole reversal, but according to NASA, it's really nothing to worry about. We're not sure we believe it'd be a completely smooth transition, but fossil records seem to show that there's no long-lasting or catastrophic events that coincide with pole reversal, no matter what the doomsday preppers and conspiracy theorist nutjobs have to say about it.

If that's not weird enough for you, we think we know where abnormalities in the planet's magnetic field first start to manifest when a pole reversal is imminent. It's in Africa, and it's called the South Atlantic Anomaly. You can think of it as a weird sort of dent where magnetic properties get all screwy. It's even a problem for NASA, as it can do some serious damage when it interferes with passing satellites. We know about the history of it from an even weirder source: the ritualistic burning of African huts and villages. The ritual preserved a huge amount of information and data in the soil levels, melting material and preserving an imprint of its magnetic field at the time. What's it all mean? Right now, the official, scientific answer is a resounding, "Ah'unno."

One volcano has been constantly erupting for at least 2,000 years

It's called the Stromboli volcano, and it's just north of Sicily. It hasn't just been erupting regularly for the last 2,000 years — volcanic researchers estimate that it also may have been erupting for around 1,000 years before that, and it's so regular that it spits out some of Earth's innards every 20-30 minutes. Those eruptions throw glowing pieces of lava into the air up to several hundred meters above its crater, and it's so frequent that locals call it the Lighthouse of the Mediterranean. A few times a year there's larger explosions, and every 2-20 years, the volcano erupts with lava flows.

That's not all it does, either, and there have been several times in recent history (1919, 1930, and 2002-2003) that eruptions have been severe enough to cause significant property damage and casualties. The eruption in 1930 was one of the worst — witnesses said there was no warning and no change in the volcano's relentless eruptions, before the massive blast led to rockslides and tsunamis that wiped out several villages and killed at least six people. That eruption can happen at any time, and if (or rather, when) it happens again, very likely it'll kill any number of tourists who, for some reason, think it's a great idea to spend their vacation sleeping near a constantly active volcano.

The fata morgana

A fata morgana is an optical illusion on a massive scale, so unlikely that it's even named for the mystical Morgan of Arthurian legend. It's undoubtedly been happening for ages, but the first real, rational observations we have on record come from a Jesuit priest writing in Sicily in the middle of the 17th century.

Father Domenico Giardina wrote about eyewitness accounts of looking across the Strait of Messina and seeing an entire city form in the air above the water. Witnesses could see people walking, until a wave appeared and seemingly washed the whole thing away. Fortunately, he was as much a man of science as he was of faith, and he postured that the sight had something to do with a particular convergence of conditions, the reflection of light, and the presence of water vapor in the air.

He was sort of right. It all has to do with the right mix of cold, dense air, the reflection of light, and the curve of the Earth. When it all comes together, light and moisture in the air can reflect images of things out of your line of sight, past the horizon and so far around the Earth's curve, we can't see the real thing. The reflection puts the image into the sky, and it's scary as Hell.

This might also explain a lot of weirdness that's been reportedly going on at sea for centuries, including one of the most legendary of ghost ships, the Flying Dutchman. Now that we understand the science, we've recorded a few times that it's happened. In 1891, the image of Toronto appeared over Lake Erie and off the shores of Buffalo, so detailed that witnesses could see individual buildings and even the church spires. It's also been theorized as to why the crew of the Titanic might not have seen looming icebergs, as it's entirely possible that the danger was obscured by an otherworldly mirage.