The Truth About One Of The Last People Living In An Iron Lung

In the 1940s and 1950s, the United States was under the grip of an epidemic. Polio, which has a messed up history, ravaged many cities and sickened many children. According to the CDC, polio is a life-threatening disease from poliovirus that can cause paralysis. Incredibly contagious, polio makes it difficult for people to breathe because of muscle weakness, which can live on in an infected person for years. Back in the 1940s and '50s, a lot of those who got sick were children. Some got so bad that they needed the assistance of a machine called an iron lung to breathe. For many of us today, the idea that people had to use an iron lung to stay alive seems unfathomable. But, there is a dwindling number of people who still use iron lungs. One of those, Paul Alexander, who spent most of his life — more than 70 years — inside the life-saving machine, died on March 11, 2024, per NPR.

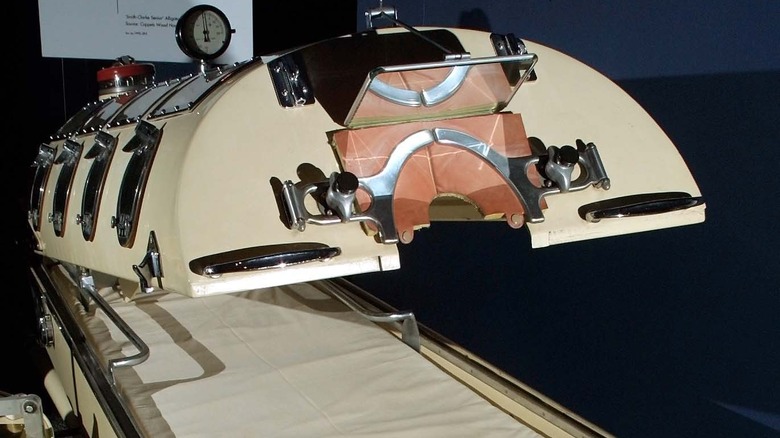

Some patients who had polio never fully recovered. Instead, they needed to spend time inside a chamber to breathe. An iron lung, or as it's also known, the tank respirator, is a type of negative pressure ventilator that does the breathing for a person. As a paper from the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine explained, people are placed on a flat frame that pushes into the machine. Their head sticks out, and mirrors are placed around them so they can see what's going on. They stayed in for hours.

He was just playing outside

Alexander was 6 years old when he got polio. He told The Guardian it was July 1952 when he developed a fever. Days before, he had been playing in the mud around his Dallas, Texas home. What he didn't know, but his parents understood, was that polio was sweeping across the country that summer.

His mother made him leave his shoes outside; polio is often transmitted through feces and droplets of bodily fluids, so it could have been mixed in with mud or rain. Alexander's symptoms got worse in the next few days. He started to feel pain in his limbs and couldn't hold anything. At one point, he had to get surgery to remove congestion in his lungs that his body, by then paralyzed, couldn't cough out.

When Alexander woke up, he was encased in an iron lung. Even though he eventually recovered from the infection, it left Alexander paralyzed from the neck down. From then on, he had to remain in the iron lung. He managed to learn how to breathe on his own, which allowed him to leave the lung for several hours at a time, but he had to sleep in it every night.

At 21, he graduated high school, the first person in his school to finish without physically being there. He got into college and went on to law school. Even though Alexander still used an iron lung every night, he could go to court and represent clients in a modified wheelchair that held him upright.

He wants you to get vaccinated

Up until Alexander's death, he continued using an iron lung. In the years since he came down with polio, he became an activist, urging people to be vaccinated. The reason why polio is not as pervasive as it once was is directly related to the use of the vaccine developed by Jonas Salk — who was often despised while he was alive — in 1955. The United States no longer sees high polio cases, though it hasn't been eradicated entirely, like smallpox.

Alexander said he wanted people to get vaccinated because if they don't, diseases like polio could come back with a vengeance. And he knew better than most what it was like to live with a condition that is now easily preventable with the prick of a needle. (You can probably guess how Alexander feels about the anti-vaxxer movement.) He simply hoped the world would no longer have to see rooms filled with iron lungs keeping people alive.

Most people who needed long-term use of an iron lung were not expected to live past their teenage years, but Alexander pushed on to age 78, outliving his parents and an older brother. Martha Lillard, who is 75, is now the last known American still living in an iron lung.

Death at 78

In his final years, Paul Alexander remained confined to his iron lung, unable to work, and was "taken advantage of by people who were supposed to care for his best interests," according to a GoFundMe page that raised more than $140,000 for him. Thankfully, Alexander had friends and a younger brother who were there to help, along with strangers who donated money. One man even provided Alexander with the machine that helped keep him alive. Keeping an iron lung in working condition requires not just hard-to-get replacement parts, but also a mechanic who knows how the machines work. A local engineer, Brady Richards, learned that Alexander's iron lung was in disrepair and provided him with a refurbished model he had at home.

Even while confined to the iron lung for more than 70 years, Alexander achieved much, not just as a lawyer and activist, but as a writer as well. He self-published his memoir "Three Minutes for a Dog: My Life in an Iron Lung," by using a plastic stick to peck out the words on a computer as well as by dictating to a friend. "Paul took a lot of pride in being a positive role model for others," Christopher Ulmer, his friend who organized the fundraiser in 2022, told NPR. "More than anything I believe he would want others to know they are capable of great things."