How We Learned No Two Snowflakes Are Alike

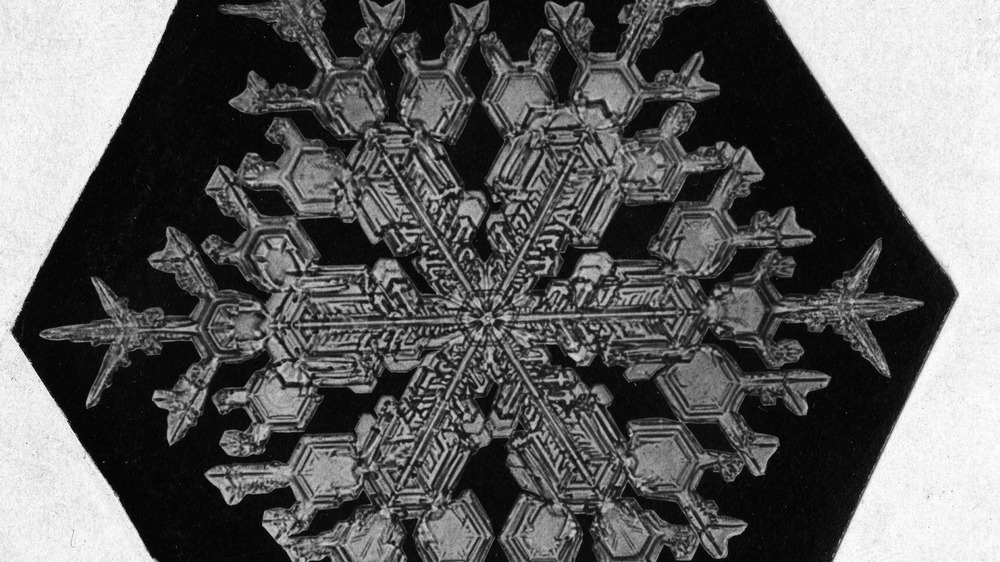

Sometimes science starts in the most unlikely places. According to Mental Floss, Wilson Alwyn "Willie" Bentley accidentally discovered that no two snowflakes were similar in his attempt to photograph their perfect beauty. His "research" — the more than 5,000 photographs and field notebooks he created — helped establish the theory that no snowflake looks like another snowflake.

Bentley, born on a small farm in Vermont, was a curious child. His mother, a former teacher, homeschooled the boy and provided him with a microscope and her old set of encyclopedias to facilitate his learning. As a boy he collected stones and birds' feathers and was fascinated by snowflakes. Bentley put snowflakes on his microscope's slide and drew what he saw in a notebook before the ice crystal melted. Unsatisfied with the results, he sought a better way to capture the images more perfectly and quickly.

He used a bellows camera, a primitive machine that captured still images, and experimented to discover the best way to immortalize the ephemeral snowflakes as he taught himself photomicrography – photographing items through a microscope. On January 15, 1885, he took a good image of a snowflake — the first person to capture one on film, according to Snowflake Bentley.

"The day that I developed the first negative made by this method, and found it good, I felt almost like falling on my knees besides that apparatus and worshiping it," he said, according to The Guardian. "It was the greatest moment of my life."

Finding the perfect snowflake photos

He was almost 20, and just starting his research. He went on to build a collection of images, notes and meteorological records using scientific methods as he studied snowflakes. He kept a velvet-covered tray outside where he gathered the snowflakes, and then he'd use a pre-chilled glass microscope slide to keep the crystal from melting before he photographed it.

Bentley also looked at rainfall, making 344 measurements of raindrop size from 1898 to 1904, reported The Guardian. He studied fog and dew, according to the Encyclopedia on Nineteenth-Century Photography, and did all this while working on his family's farm. His findings were published in journals and magazines such as Scientific American, National Geographic and The National Weather Service Research Journal. His book, "Snow Crystals," remains in print.

He had his detractors. A German scientist, Gustav Hellmann, accused Bentley of manipulating his amazing images after seeing that a collection of a colleague's photos were underwhelming. He said that Bentley "mutilated the outlines," according to a New Scientist article. Bentley's sorry-not-sorry response? "A true scientist wishes above all to have his photographs as true to nature as possible, and if retouching will help in this respect, then it is fully justified," he said.

Bentley continued his work until he died from pneumonia in 1931, age 66. The Bentley Snow Crystal Collection, consisting of slides and journals donated by Bentley's niece, Alice Hamalainen, is housed at the Buffalo Museum of Science.