The Crazy History Of The Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) has the dubious honor of being the most popular amendment that's never passed. According to the National Archives, over 1,100 amendments related to the ERA have been introduced to Congress. That's about 10% of the total number of amendments. And it's not just the people on Capitol Hill who really want an amendment prohibiting sex discrimination to be added to the Constitution. A poll from early 2020 showed that around three quarters of Americans support the ERA.

The ERA came very close to passing nearly 50 years ago. After festering in Congress since 1923, in 1972 it was forced onto the House floor by one determined Congresswoman (who you've probably never heard of) and found bipartisan support. But the efforts of an equally determined anti-feminist not only stopped the ERA in its tracks, they reversed the course of women's rights forever.

The ERA has been making headlines again recently, but a missed deadline, backtracking states, and criticism from an unexpected source have left its future uncertain. This is the crazy past, present and future of the ERA.

The Equal Rights Amendment first went to Congress in 1923

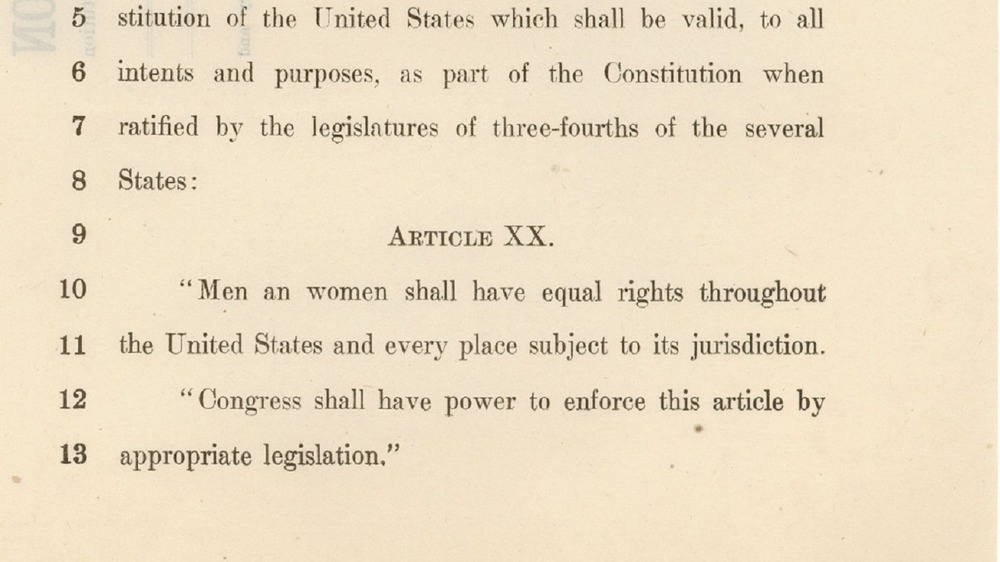

The first version of the ERA was written by suffragette Alice Paul in 1923 on behalf of the National Woman's Party (NWP). The text said, "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction."

Founded by Lucy Burns and Paul in 1913 as the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, the NWP used confrontational tactics to demand votes for women. According to The New York Times, they were arrested for holding silent protests outside the White House, and in 1913, 8,000 marched on Washington, where the police allowed male onlookers to spit at, slap, and burn them with cigarettes.

The ratification of the 19th Amendment was certified on Aug. 26, 1920. It technically gave women the right to vote, although many women of color would continue to be prevented from exercising it. With their original goal achieved, Paul and the NWP moved on to establishing broader rights for women through a further amendment.

Paul drafted the ERA, and the NWP launched its ERA campaign on July 21, 1923. The ERA was introduced to the House by Rep. Daniel Anthony, nephew of suffragist leader Susan B. Anthony, and to the Senate by Sen. Charles Curtis. However, they faced opposition from labor reformers, who worried that "equality" would mean rolling back the protections for working women that they'd fought so hard to earn. The ERA's progress stalled for nearly half a century.

The Equal Rights Amendment was reignited in the 1950s

Although it was introduced to every congressional session from 1923 on, the ERA kept getting stuck in legislative limbo, The Washington Post reports. In 1955, newly-elected Michigan Congresswoman Martha Griffiths picked up the torch. (Griffiths was also primarily responsible for the sex discrimination amendment of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.) In 1970, she successfully convinced a majority of the House's 435 members to sign a discharge petition, which forced the ERA out of the Senate Judiciary Committee and onto the floor for a debate and vote.

That August, the House passed the ERA 352 to 15. However, progress stalled at the Senate. Opponents added a seven-year deadline for ratification and a provision that exempted women from the draft. ERA supporters worried this might preclude women from certain public service roles. This pushed the vote on the ERA to the next legislative session.

Griffiths introduced a slightly reworded version of the ERA to the House in 1971. She included the seven-year deadline as a compromise, hoping this would win more supporters and believing that ratification would be quick. Sen. Sam Ervin (a southern Democrat who later presided over the Watergate investigation) introduced seven changes, but all were voted down. The new version passed the House 354 to 23 on Oct. 12, 1971, and the Senate 84 to 8 on March 22, 1972. Next, two thirds of the states — 38 out of 50 — had to ratify it before 1979.

The wording of the Equal Rights Amendment has changed since 1923

Given how many times the ERA has made its way to Congress, it's perhaps not surprising that it's been through a few revisions.

All versions of the ERA contain a second section that goes something like, "Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation," which was from Alice Paul's 1923 version of the ERA. The first article in that version read, "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction."

Martha Griffiths reworded this first article to read, "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." A third article was added, reading, "This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification." This article has remained the same ever since. In 1971, Griffiths added the seven-year deadline to the preamble before the articles.

Two versions of the ERA were introduced to the House and Senate respectively in 2019. The Senate version is exactly the same as the 1972 one, but without the deadline. The House version is the same except for the first line of the first article, which borrows from Paul's version. Before "Equality of rights under the law...," it adds the sentence, "Women shall have equal rights in the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction." Both were referred to committees in early 2019.

What would an Equal Rights Amendment change?

The potential impacts of adding language that prevents discrimination on the basis of sex to the Constitution are much debated.

Some people have argued that at this point in history, the ERA isn't necessary. As The New York Times explains, legal campaigns run by the likes of future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the 70s and 80s created a legacy of case precedent in which the courts ruled against sex discrimination on the basis that it violated the 14th Amendment. ERA opponents argue that these provide enough of a framework to counter sexist laws and acts of sex discrimination.

However, a list of precedent-setting cases is not as concrete a barrier against sex discrimination as a constitutional amendment. The Washington Post explains that if the ERA was passed, the courts would be forced to treat sex discrimination cases with a higher level of scrutiny than they currently have to — at the same level as a violation of any other amendment. In 2017, Ginsburg explained, "I would like to be able to take out my pocket Constitution and say that the equal citizenship stature of men and women is a fundamental tenet of our society like free speech."

That said, there would be limitations on how far an ERA would protect women from individual threats. As The Washington Post notes, amendments only apply to the government, not to private citizens, so the ERA likely would not guarantee protection from, say, domestic violence.

The Equal Rights Amendment would likely help protect LGBTQ+ people

Heterosexual cisgender women aren't the only ones who stand to benefit from having an amendment banning sex discrimination enshrined in the Constiution. By referring to discrimination based on sex rather than discrimination against women specifically, the ERA could potentially be used to protect people in the LGBTQ+ community.

In an op-ed for Teen Vogue in 2020, Danica Roem — the first openly transgender state legislator in America — and human rights attorney Kate Kelly wrote, "The word 'women' is conspicuously absent from the ERA... It holds ample potential to protect all marginalized genders — binary and non-binary alike — and sexual minorities."

Notorious ERA opponent Phyllis Schlafly certainly thought so. As the Adovcate explains, she used homophobic and transphobic arguments in her campaign against the amendment, claiming that the ERA would lead to same sex marriages and unisex bathrooms. (The former became law without the ERA in 2015, but the latter is still being wielded as a weapon against trans rights.)

Two 2020 landmark Supreme Court decisions (R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Bostock v. Clayton County) prove that sex discrimination laws can be applied to protect LGBTQ+ rights. In 2020, the court ruled that discriminating against transgender people and gay people respectively violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, because — thanks to Martha Griffiths — it bans discrimination on the basis of sex.

The Equal Rights Amendment had widespread bipartisan support in the '70s

Once Martha Griffiths and her allies had forced the ERA out of its limbo state in 1972, it received widespread bipartisan support. Note that it passed 354 to 23 in the House and 84 to 8 in the Senate.

Up to then, women's rights issues had not been divided strictly down party lines, and unlike now, the Democrats certainly weren't the proto-feminists' favorites.

In the first half of the 20th century, the Democratic Party was the party of the labor movement, which opposed the ERA as a threat to the progress it had made securing protections for working women. The suffrage amendment was passed by a Republican Congress, and the two men who sponsored the ERA in 1923 were Republicans. The Republican party included an endorsement for the amendment in its plank in 1940, beating the Democrats by four years.

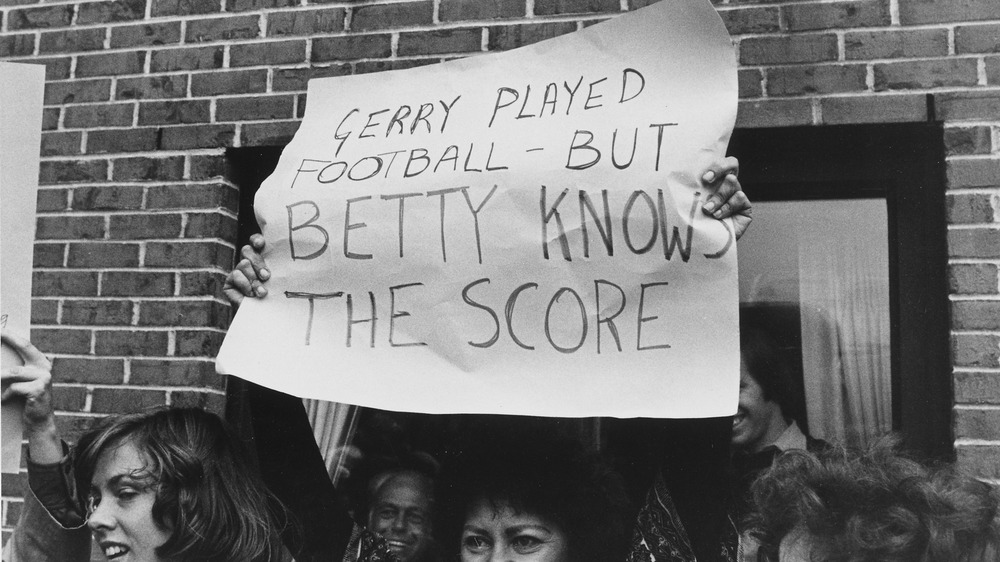

By the 70s, labor rights for women were covered by Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and many pro-labor Democrats switched positions to support the ERA alongside Republican women, including Jill Ruckelshaus and Mary Dent Crisp, the LA Times reports. Even President Richard Nixon endorsed it! First lady Betty Ford, wife of President Gerald Ford, was a staunch supporter, writing, "It is my personal opinion that ratification of the ERA is the single most important step that our nation can take to extend equal opportunity to all Americans." With support from both sides, ratification of the ERA looked like a given.

One woman personally orchestrated the downfall of the ERA

The trajectory of the ERA was dragged off course by one woman. Phyllis Schlafly was a right-wing activist who found fame among conservatives through her many self-published political books, various unsuccessful runs for office, and a monthly newsletter which she started in 1967, according to The New York Times.

Initially, Schlafly wasn't interested in the ERA and even considered supporting it. But after reading some conservative writing, she decided that it was a threat to what she saw as the privileges of being a woman. She believed that the ERA would force women to work, deprive them of alimony, see them drafted into the army (during the Vietnam War), and lead to abortions on demand.

In 1972, Schlafly made her campaign against the ERA official, founding a group named Stop Taking Our Privileges ERA (STOP ERA). Three years later, it was renamed the Eagle Forum. She and her nationwide network of like-minded women wrote to, visited, and phoned conservative politicians, challenging them to, as they saw it, "protect" women's rights to be homemakers. Hypocritically, Schlafly herself was a married mother of six who worked more hours a week than many men.

In 1977, Schlafly countered the National Women's Conference with a rival conference, featuring speeches against abortion, gay rights, and the ERA. The prominence of her counter narrative to the ERA panicked conservatives into revoking their support in favor of "traditional values," and progress on the ERA stalled.

The Equal Rights Amendment received a deadline extension — but it wasn't enough

After the ERA passed the Senate on March 22, 1972, its proponents had seven years to convince 38 states (three quarters) to ratify it.

Hawaii became the first, ratifying the ERA the same day it was issued, followed by six others within the week. On the one-year anniversary, Washington became the 30th state to ratify the amendment.

However, as Phyllis Schlafly's campaign spread, ratifications of the ERA ground to a halt. Between 1975 and 1979, only Indiana ratified the amendment, becoming the 35th state to do so. On July 10, 1978, The New York Times reported that nearly 100,000 pro-ERA demonstrators (including Congresswoman Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and Betty Friedan) were marching on the Capitol, demanding an extension to the ERA's deadline. That year, Congress granted them a three-year extension, shifting the date to June 30, 1982. But in that time, no more states ratified the amendment.

As The Washington Post reported, on July 1, 1982, the day after the second deadline expired, Schlafly threw a gala celebrating the effective end of the ERA. It was attended by multiple Republican senators and famous conservative figures. Asked if she was worried about ERA supporters' plans to continue the fight, Schlafly said, "The ERA's been dead for three years."

The end of the Equal Rights Amendment marked the end of a feminist era

Feminist history in the U.S. is usually divided into waves. Roughly speaking, the first was the fight for suffrage, which ended after the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The second started in the 60s and ended around the same time as the failure of the ERA.

Before the second wave, there had been vague bipartisan support for protecting women, but feminism was treated as a joke at best and a threat to civil society at worst. Prohibition of sex discrimination was only included in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act because Chairman of the Rules Committee, Democratic Congressman Howard Smith, thought it would kill the bill. And indeed, it provoked laughter on the House floor, until Congresswoman Martha Griffiths pointed out that this response proved that sexism was rampant and needed to be addressed.

The early days of the ratification process indicated that the feminists' hard work throughout the 60s and early 70s to make women's rights mainstream had paid off. But Phyllis Schlafly's rise to fame and the STOP ERA's success at killing the amendment marked a turning point towards the more conservative attitudes of the 80s and beyond. The Washington Post reported that future president Ronald Reagan sent a congratulatory telegram to Schlafly's gala, celebrating the amendment missing its deadline. Shortly before her death in September 2016, Schlafly signed on to another right-wing swing, endorsing Donald Trump for president.

The Equal Rights Amendment was resurrected in 2017

Exactly when the third wave of U.S. feminism started is unclear, but it was somewhere during the mid to late 2010s. In 2017, the ERA returned to the agenda, thanks to Democratic Sen. Pat Spearman of Nevada, who convinced both state legislatures to ratify the amendment. As one of two openly gay senators, she argued that, "The Equal Rights Amendment is about equality, period," NPR reports.

The New York Times found that the election of President Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016, followed by the sudden explosion of Tarana Burke's #MeToo Movement, lit a spark in future feminist activists who had assumed that much of the fight for gender equality had been won before they were born. Suddenly, having sex discrimination explicitly prohibited by the Constitution seemed as important as ever.

The following year, in 2018, Phyllis Schlafly's home state of Illinois became the 37th state to ratify the ERA, according to Reuters. And in 2020, Virginia took the amendment across the finishing line — nearly 48 years since the Senate voted it through — becoming the much-needed 38th state.

The Equal Rights Amendment could end up in the Supreme Court

In 2020, the ERA finally found its 38th state. But opponents still argue that the fact it missed its deadline by 38 years (one year for every state needed to pass it) means that it's the legislative equivalent of a ghost.

In February 2020, a few weeks after Virginia ratified the amendment, The New York Times reported that the House of Representatives had voted 232 to 183 to extend the deadline, a move that theoretically pushed the amendment closer to finally passing. However, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who opposes the ERA, refused to bring it to the Senate floor in 2020.

Ultimately, the ERA's fate might hang in the courts, not Congress. In December 2019, the attorneys general of Alabama, Louisiana, and South Dakota sued to stop ratification, based on the expired deadline. But in January 2020, the attorneys general of the three most recent ratifying states — Nevada, Illinois, and Virginia — sued to force the archivist of the United States, David Ferriero, to pass the amendment.

They argued that the deadline isn't part of the actual article, that Congress doesn't have an explicit constitutional right to enforce a deadline on amendments, and that the most recent amendment, the 27th (which regards salary increases for Congress), was passed in 1992 after taking more than 200 years to reach 38 states. According to the Associated Press, many legal observers expect to see the issue reach the Supreme Court.

The Equal Rights Amendment might need a total rehaul

Not all feminists agree that the resurrection of the ERA is a good thing. In February 2020, days before the House voted to extend the deadline, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said that she'd prefer to see the 1972 version of the ERA laid to rest and a new version introduced, with the ratification process starting from scratch. According to The New York Times, she told an audience at the Georgetown University Law Center, "I'd like it to start over. There's too much controversy about latecomers."

At the same event, Ginsburg also pointed out that five states — Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, and South Dakota — have all attempted to withdraw their ratification of the ERA, adding, "if you count a latecomer on the plus side, how can you disregard states that said 'we've changed our minds?'"

With such an influential voice turning against the very legislation she helped push for, and the ERA's Congressional future uncertain, the crazy part of the history of the Equal Rights Amendment isn't over yet.