This Is How The Legend Of Lawrence Of Arabia Was Born

The exploits of T.E. Lawrence during World War I made him the stuff of legends. According to the BBC, his innovative tactical mind and knack for guerrilla warfare helped Arab rebels in Jordan and Syria rise up against Turkish rule, and he was a staunch advocate for Arab independence. But he didn't go to the Middle East as a soldier. He first went to Syria and Palestine as an archaeological student from Oxford in 1909. When the war broke out, he served as an intelligence officer in Cairo, Egypt, then joined forces with the Arabs. As noted by Michael Korda, whose biography of Lawrence was reviewed in the Christian Science Monitor, Lawrence developed several guerrilla tactics to help the Arab insurgents achieve victory, despite being drastically outnumbered by the Ottoman Turks. Many of these tactics, such as hit-and-run attacks and improvised explosive devices, are still in use by guerrilla fighters to this day.

Yet, by the time he enlisted in the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1922, his name was so well-known that he had to enlist under a pseudonym in attempt to find a bit of anonymity. And still, he was so popular that he was found out and discharged the following year, because his superiors deemed his celebrity a hindrance to his service. And all this notoriety was thanks to the influence of one man, an American journalist who saw something in Lawrence that he knew audiences the world over would just eat right up.

Journalist Lowell Thomas created the legend of Lawrence of Arabia

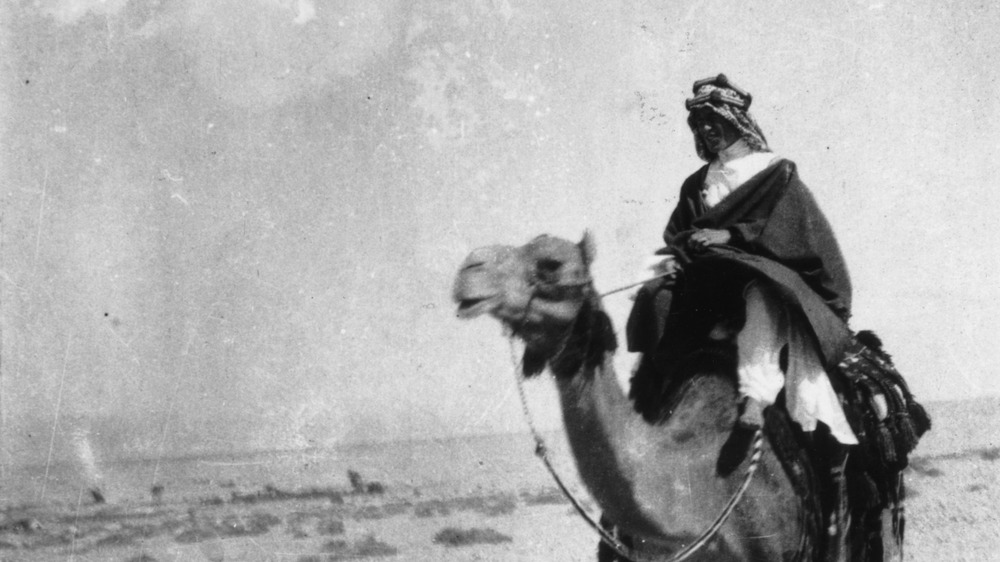

Lawrence's life would change forever after he received a visit from Lowell Thomas, a journalist from Chicago who had documented a British campaign to take Jerusalem in 1917. It was in that city that Thomas met Lawrence. According to PBS, Lawrence was reportedly introduced to the journalist as the "Uncrowned King of Arabia." Thomas and his cameraman Harry Chase were invited out to the desert camp of the Arab Prince Feisal (sometimes spelled Faisal), and there they took photos and filmed Lawrence interacting with the insurgents.

The footage and photos they got from that trip would go on to fascinate audiences all over the globe. People were tired of hearing about the horrific aspects of that supposed "war to end all wars," and Thomas's Lawrence of Arabia was a smash hit right out of the gate. The tale he told of a "mysterious blue-eyed Arab in the garb of a prince wandering the streets" created an instant legend. The show premiered in New York, then moved to London, where its planned two-week run was prolonged to six months. From there, the show went on to wow people from Australia and New Zealand to Southeast Asia, India, and Canada. Whether he liked it or not, T.E. Lawrence — or rather, Lawrence of Arabia — had become a household name, and he would find it very difficult to live a normal, quiet life after that.

Lawrence of Arabia was allegedly not a fan of his legendary status

After Thomas's show became a global sensation, Lawrence (above, left, with Thomas) would reportedly claim that the journalist had taken advantage of him during their time at Prince Feisal's camp. They argued over the nature of how it all went down. Lawrence said Thomas had been around only a couple days, while the latter said he'd been allowed to film for weeks. Lawrence — a man with a genius tactical intuition — even went so far to claim he'd been "tricked" into being photographed and filmed by Thomas. According to History.net, Lawrence later wrote to his friend, the British novelist E.M. Forester: "I resent [Thomas]: but I am disarmed by his good intentions. He is vulgar as they make them: believes he is doing me a great turn by bringing my virtue into the public air." For his part, when Thomas was asked about Lawrence's allegations, he replied, "He had a genius for backing into the limelight."

And there may have been something to that, for Thomas wasn't the only one bringing Lawrence's virtues into the public air. Lawrence himself helped to that end when he wrote a 700-autobiography of his time with the Arab insurgents. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom was published in 1926 to a limited group of subscribers, and an abridged version became an instant bestseller when it went on sale to the general public the following year.