What It Was Really Like Being A Teenager During The Civil War

War is hard for everyone. It's often a brutal, grimy situation even for people who find themselves far behind battle lines and definitely for those who are in the middle of the action. The American Civil War proved to be especially difficult for people in the not-so-United States.

As per the American Battlefield Trust, the Civil War was by far the bloodiest conflict on American soil, with an estimated 620,000 military deaths, more than World War I and World War II combined. Some of the war's skirmishes, like the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, were so traumatic that they've remained embedded in the national psyche for over 150 years. Even after the war officially ended in 1865, as History reports, the impact of the nation-rending war has echoed down to the present day.

That sort of destruction reaches far and wide, regardless of someone's location or age. Teenagers transitioning from childhood to adult life were especially affected by the war. Depending on their individual situation, a teen might have become a soldier, fled for their own freedom, or defiantly snubbed occupying soldiers. Some were enthusiastically patriotic, while others were skeptical of the war, or else tried simply to carry on with their lives as they had done before. Even for the most spoiled amongst them, being a teenager during the Civil War was hardly easy.

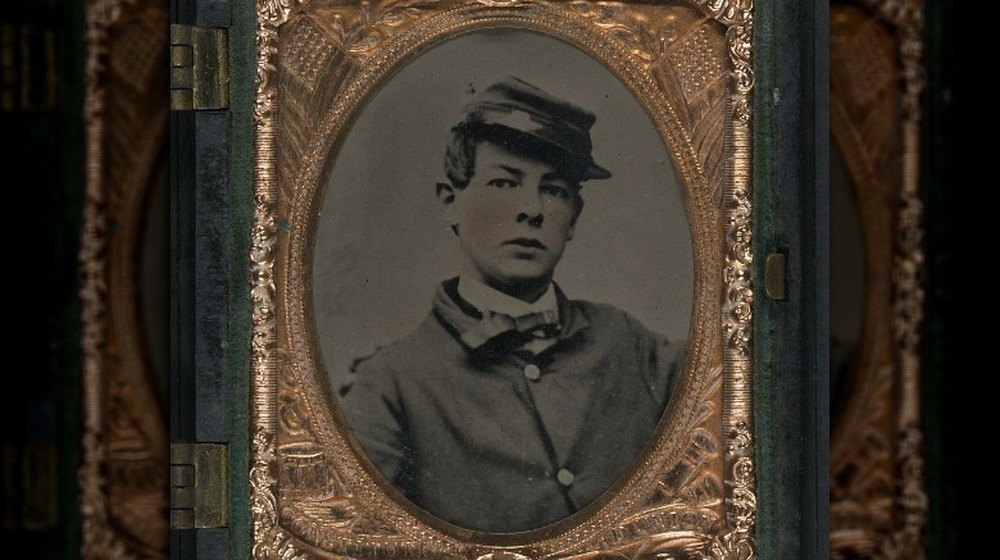

Many Civil War teenagers were child soldiers

According to the National Park Service, an estimated 100,000 soldiers in the Union army were 15 or younger. Some 300 of those child warriors were under 13 and, shockingly, an estimated 25 were under 10. Most of the youngest were enlisted as little more than musicians, playing drums and fife for the older soldiers. Numbers for the Confederacy are less clear, but it appears that up to 20% of the total soldiers involved in the war were 18 or under.

Some especially eager enlistees fudged their birth dates, the American Battlefield Trust reports. Elisha Stockwell first joined the Union Army at just 15 years old, though his memory got conveniently hazy when he was in front of the recruitment officer. "I told the recruiting officer I didn't know just how old I was but thought I was eighteen," he later recalled. For most of the war, soldiers on both sides had to be at least 18, while musicians were to have been 16 at minimum.

Even drummer boys, who were supposed to stay out of the action, could get caught up in the war's bloody chaos. PBS reports that some took up arms in the moment, as their comrades suffered both quick and painful, lingering deaths. Others helped surgeons, who often treated battlefield wounds in horrifying hospital tents without anesthetics. No wonder, then, that those who returned home often carried physical and mental scars for the rest of their lives.

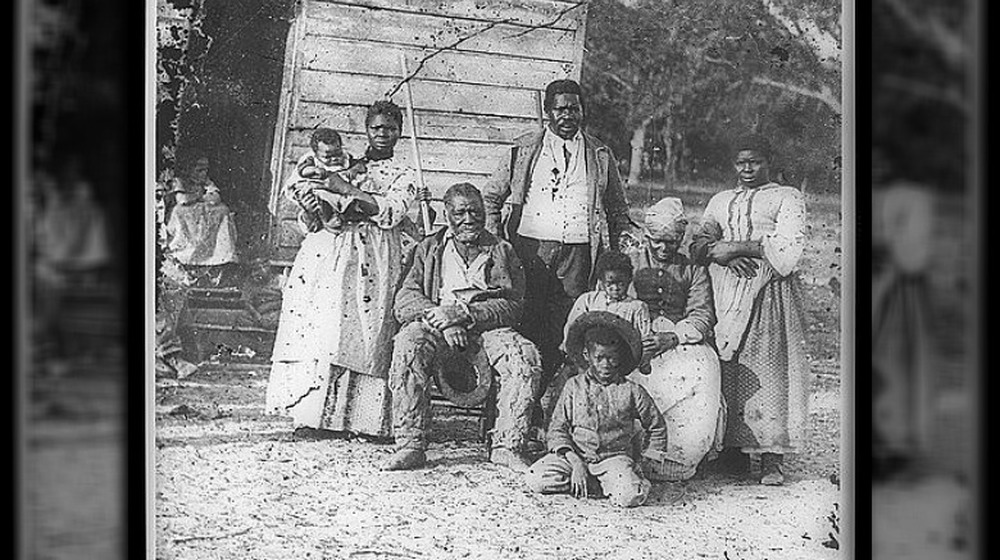

Enslaved teenagers faced brutal conditions during the Civil War

The Civil War brought great economic and social upheaval to the American South. People in all situations felt the effects of this change, but none felt it more brutally then enslaved people. Throughout the South, African-American teenagers were compelled to face traumatic situations and fight for their own freedom, despite their young age.

NCPedia says that, as the Civil War encroached further and further into southern territory, it began to increase the workload on enslaved teens. Some were forced into grueling fieldwork at increasingly younger ages. Boys might accompany their masters onto the battlefield, while girls were recorded as having sewn for the Confederate cause or even caring for wounded soldiers.

For some teenagers and their families, their freedom must have seemed achingly close. As per The Washington Post, many slaves had learned that the Union commander of Fort Monroe in Virginia had declined to return runaway slaves to their masters. As word got out, more and more slaves left for Fort Monroe and other Union encampments, where they were treated as property-like "contrabands" rather than people and lived in crowded, often dirty camps. Still, with the knowledge that the North contained anti-slavery abolitionists, this would have been an important step for teens seeking a better, more free life away from the plantations.

Freed African American teenagers had to get serious

Freed slaves dealt with rough economic conditions and entrenched racism. Teens in freed communities often had to work harder and behave better than their white counterparts to get ahead in life.

As per the National Park Service, the younger an African-American person was, the smaller their rations while enslaved. They faced similar restrictions in contraband camps, formed of people fleeing enslavement by setting up in Union territory, after it had become clear that officials generally weren't going to return slaves to their masters. These camps became even more crowded with the Confiscation Acts of 1862, which officially freed all slaves who crossed the line into a Union state. Ultimately, about half of those formerly enslaved people were children.

Teenage "contrabands," as they were sometimes called, often had to prove themselves through humble, occasionally degrading work like ditch digging and washing laundry. In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln officially freed "all persons held as slaves," allowing for African-American teens to join the Union Army as yet more child soldiers.

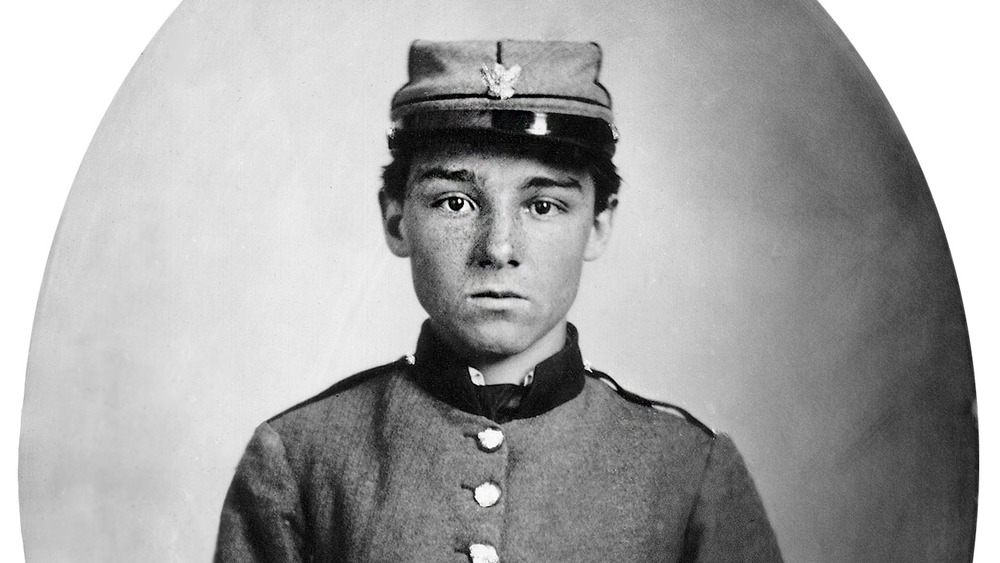

One of the most famous Civil War portraits is of a teenage soldier

After the end of the war, the photograph of Pvt. Edwin Francis Jemison, a teenage Confederate soldier, became an icon of the Civil War. If you've picked up a history of the war in a bookstore, you've probably seen his face. Jemison's somber expression seems to epitomize the tragedy of the conflict, especially given that he died at the tender age of 17. As per the Civil War Book Review, Eddie, as his family called him, enlisted when he was only 16 years old.

Yet, as HistoryNet reports, the true story of Jemison and his demise has been buried for many years. He died at the Battle of Malvern Hill in 1862, with some stories saying he did so in rather gruesome fashion. Two reports claimed that Jemison had met his end when a cannonball connected with his head. Yet, those stories are suspect. One man, Capt. Warren Moseley, claimed to have been right next to Jemison when the younger soldier died, though a timeline of Moseley's experiences during the war makes that claim impossible.

Moreover, Moseley enjoyed acclaim and the occasional payout for many decades as a "professional veteran," regaling his fellow southerners with tales of the conflict and organizing reunions. It could be that Moseley felt compelled to tell a dramatic, tragic story when he talked about Jemison. Ultimately, how Jemison died at Malvern Hill is still unknown.

Teenagers worked to support soldiers on both sides of the Civil War

While some teenagers left their homes for the battlefield, others remained behind. In the absence of both their fellow teens and other adults who went to war, many were forced to pick up the slack. According to the American Battlefield Trust, American youth at the time would have taken on more duties to help tend farms, manage livestock, run the home, and even help manage family businesses. Some were still able to attend school, but others were forced to drop out when the funding for local education dried up or their teachers themselves went away to fight.

Teens and other children could also be brought into the ongoing war effort, which only intensified as the Civil War progressed. NCPedia reports that older youths in the South worked in ammunition factories and sometimes appeared as clerks or other support staff in government offices. They also rounded up supplies and food for the soldiers. Some even gathered up scraps of lint to make absorbent bandages that could help staunch a soldier's battlefield wounds.

Many teenagers were expected to carry on their life from before the Civil War

While, throughout both the North and the South, the daily lives of children and teenagers were often upended, some were expected to carry on as before. For numerous middle- and upper-class teens, their families pushed them to still continue with their education and, for as long as possible, their participation in social and community life.

For Saida Bird, that could start to pile on quite a bit of pressure. As per the American Battlefield Trust, she was born into an educated, upper-class southern family that owned a large number of slaves and operated a cotton plantation in Georgia. In 1862, when Bird would have been about 13 years old, her mother wrote to her daughter, saying, "I hope you are not idle, but busily improving your time." She instructed Bird to keep up her music lessons, read her Bible regularly, and stay away from unapproved novels, lest the teen "poison your young mind with improper reading," in her mother's words.

Bird also described evening walks with her cousins, concerts, dances, French lessons, and other aspects of daily life for well-off southerners. Still, the war came for her, anyway. Bird was clearly aware of the conflict, as her mother volunteered in army hospitals and Bird herself sewed some garments for her father and other Confederate soldiers.

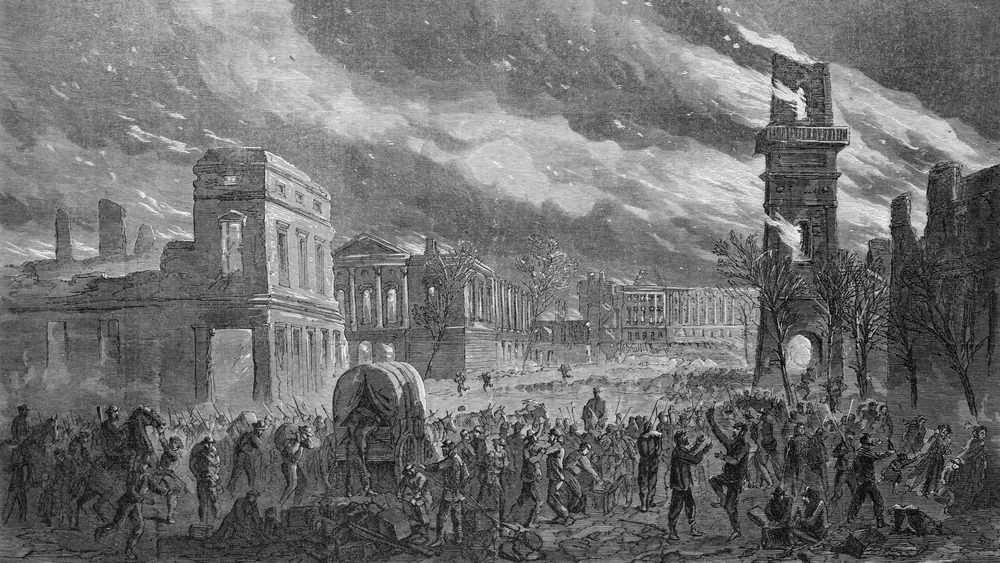

In the South, some teenagers nearly starved

While some teens in the American South were able to hold on to pieces of their daily lives from before the war, others simply could not. Towards the end of the Civil War, Union troops occupied major cities and wreaked havoc throughout the region.

The American Battlefield Trust relates accounts from children and teenagers who saw the upheaval firsthand. In North Carolina, one girl saw families wandering the streets carrying their belongings, rendered homeless when soldiers had torched their residences. Others experienced dangerous bombardments from enemy forces, narrowly escaping with their lives.

Union soldiers were also known to steal from southern families, both out of hunger and a desire for vengeance as the long, bloody war reeled onward. One 17 year old in Sandersville, Ga., known only in the record as "L.F.J.," found herself a widowed young mother facing starvation brought by these soldiers. According to her account, reproduced by the University of Houston, she watched helplessly as "Yankee ruffians" decimated her family's food stores of grain, meat, and vegetables. She later wrote that she "knew that now our last hope for food was gone.... That night we went to bed supperless ... sadder now was the thought, 'The cows are killed. I will be so hungry I cannot nurse Baby.'"

Some teens were very skeptical of the Civil War

While communities on both sides were often very patriotic and supportive of their respective troops, some teens, like Mary Seline Whitcomb, were deeply unsure that the Civil War was justified.

Inquiries Journal reports that Whitcomb was the daughter of a well-off New Hampshire farmer who kept a diary from 1858 to 1864, beginning when she was 14 years old. By the time she was 17, she wrote about the attack on Fort Sumter, which began the Civil War after years of increasing tensions amongst the states.

Though she would never be able to legally vote or really participate, Whitcomb was well aware of the partisan politics that affected both her town and the nation as a whole. Her writings present a complicated view of the war. She declined to take part in Union War-Clubs, as other women did, but neither was she vehemently against her male counterparts going off to war. When her brother, George, was drafted, she found it "terrible to think that he was taken and to be pressed into service. Almost like death." Her family, overall, tended to adopt an anti-war stance expressed by some northern Democrats, reflected vaguely in Whitcomb's account.

In the South, teenage girls were defiant to northern occupiers

Throughout the South, people in Union-occupied towns weren't keen on their new neighbors. According to the Journal of the Civil War Era, southern citizens routinely resisted the northern military government through acts like declining to take loyalty oaths or verbally abusing Union soldiers. One woman in Nashville bewailed the appearance of a majority Black regiment, writing that, "I would willingly live on bread & water in the south, where there is liberty and society such as we once enjoyed."

While adults could be fined or jailed for openly resisting, teenage girls seemed to have more leeway. Children and Youth During the Civil War Era reports that teens in Union-occupied New Orleans sometimes changed their dress to reflect Confederate support and socially snubbed northerners. Oftentimes, this was interpreted as high-spirited but harmless youthfulness.

Sometimes, however, teens could get too rowdy even for indulgent officers. GoKnoxville relates the story of Ellen Renshaw House, a young Knoxville resident who described herself rather hyperbolically as a "very violent rebel." Though she didn't get deadly, House did cause waves when she encouraged a group of girls to wave at Confederate prisoners. House also reportedly insulted the wife of a Union officer, though she said, "That is about the only thing they could accuse me of that I have never done."

Ultimately, Union forces kicked House out of Knoxville entirely in the spring of 1864. She would not return to the city until after the war.

A few teenagers were trapped during the bloody Civil War battle at Gettysburg

Some teenagers were confronted with the war literally on their own doorsteps. For Tillie Pierce and a small group of other teens and children, their efforts to avoid bloodshed put them even more in harm's way.

According to the Tillie Pierce House, Matilda "Tillie" Pierce was born in 1848, making her 15 years old when the Union Army marched through her hometown of Gettysburg, Penn., in July 1863. Worried for her safety, Pierce's family urged her to pack up and stay at Jacob Weikert's farmhouse, which they thought would be far from the action. Unfortunately, the battle grew alarmingly close. During the Battle of Gettysburg, Pierce provided supplies to the soldiers and assisted medical staff in caring for wounded men. When she was able to return to her own home a few days later, she wrote in her memoirs, At Gettysburg, "I felt as though we were in a strange and blighted land."

Pierce was far from the only teen who experienced Gettysburg firsthand. The American Battlefield Trust reports that 15-year-old Albertus McCreary saw Union soldiers streaming through the town. One officer told them to shelter in their basement or risk being killed after battle had grown alarmingly close. McCreary's sister, 17-year-old Jennie, kept busy rolling bandages for wounded soldiers. She had worried that she couldn't help injured people, but, as she later said, "I find I had a little more nerve than I thought I had."

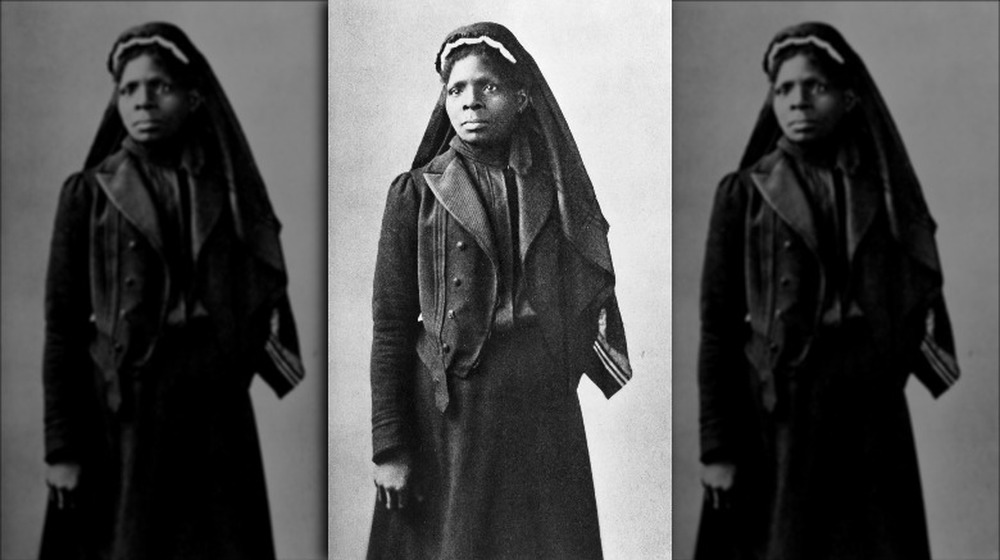

Susie King Taylor was a teenage nurse and teacher

Born into slavery in 1848, Susan Baker, later known as Susie King Taylor, experienced a dramatic escape to freedom. Before that, she had to overcome barriers to her education. In 1855, according to the American Battlefield Trust, Taylor was allowed to live with her free grandmother in Savannah, Ga. Though she was legally forbidden to pursue an education, Taylor learned to read at two secret schools.

When she was only 14 years old, the National Park Service says, Taylor fled with her uncle and a small group of other slaves to a Union gunboat near Fort Pulaski, which was currently under the control of Confederate troops. Taylor went to live in a freed slave encampment on St. Simons Island, a Union-controlled bit of land off the southern coast of Georgia.

Because she was literate, 14-year-old Taylor quickly became the lead educator on St. Simon's Island, making her the first Black teacher to openly educate other African Americans in Georgia. In a letter, she recalled having to teach an estimated 40 children, along with multiple adults who also wanted to learn how to read. In 1862, the teenaged Taylor married Edward King, an officer in the 33rd United States Colored Infantry Regiment. She became a nurse and laundress for his regiment, while still working as a literacy teacher for the soldiers. After the war, she continued her work as an educator and published her memoirs, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp.

Romantic life was tough for some Civil War teenagers

While bigger things were definitely happening during the war, teens still lamented struggles that would feel very familiar indeed to teenagers today. Namely, no matter the time, it seems like it was always tough for teens to find a date.

One Confederate girl, Emma Riely, wrote of her difficulty finding a beau when all that were available were Yankee soldiers. Children and Youth During the Civil War says that Riely was born in 1847, placing her solidly in the teenage category during the height of the Civil War. Riely, who came from a relatively wealthy slaveholding family, was devoted to the Confederate cause. Like many girls at the time, she also wanted to find a young man. That got especially tough once all of the eligible southern gentlemen went off to war, and Union troops occupied her town of Winchester, Va.

While some could have shelved their Confederate-leaning patriotism for a date or two, Riely promises that she did not. When a Union officer suggested that she simply wear a veil during a sleigh ride so no one could see that it was her, she told him that, no, "her conscience would be behind that veil." According to A Girl and a Soldier, in 1865, Riely married Reuben Conway Macon, a properly Confederate veteran.