Theories About What Really Killed These Historical Leaders

Even today, with our fancy science and thousands of years of experience behind us, we just barely understand the process of death. But because of all that fancy science, we have come to expect a level of certainty on the subject, especially when it affects celebrities or our political leaders. When a head of state or party leader dies, we assume there will be an autopsy and a coroner's report explaining exactly how they went.

That kind of scientific certainty about causes of death is a relatively recent development, though. It wasn't all that long ago when figuring out why someone had just dropped dead in front of you was more guesswork than science—and even in the modern era there's often a lot of mystery and doubt when people die under difficult circumstances, or when autopsies are prevented. That's what we invented conspiracy theories for, after all.

That's why this list exists, to explore the theories about what really killed these historical leaders. Some of them died in the days when doctors literally believed something called "humors" caused disease, some died exhibiting conflicting symptoms—and some under extremely sketchy circumstances. What ties them all together is a lack of certainty about how they died, and the elaborate theories that have sprung up around that question.

Elizabeth I: Lead poisoning

After a rocky start for the Virgin Queen (her legitimacy was a lingering question), Elizabeth I matured into one of England's longest-reigning monarchs. While her legacy as queen is complicated, she brought stability to the kingdom.

Elizabeth was a woman at a point in history when women had few rights or legal powers, which made her occupation of the throne complicated. It also made her body and reproductive potential extremely valuable, which ultimately led her to cultivate an image as the Virgin Queen in order to take control (as All About History notes, this also led to a conspiracy theory that she was secretly a man). She used extensive makeup and costuming to present a carefully orchestrated public image to her country—porcelain skin, red hair, elaborate clothing. And as the Royal Museums Greenwich reports, that makeup may have killed her.

Elizabeth I died at the age of 69—not bad for the 17th century—after a lengthy depression in the wake of several old friends passing away. She reportedly behaved oddly, standing still for hours at a time, and often wept openly. Some suspect that the lead-based white makeup she covered herself in for decades had caused blood poisoning. As Medical Bag notes, the makeup Elizabeth used was definitely lead-based, and her behavior near the end is in line with the symptoms of lead poisoning.

Alexander the Great: Guillain-Barre Syndrome

When Alexander the Great was just 32-years-old, he was the ruler of one of the largest empires ever created. And then, after a rapid decline which saw him suffer fevers, increasing paralysis, and eventual loss of the ability to speak, he died suddenly in 323 B.C. Oddly, his body didn't decompose for several weeks after his death.

It's not uncommon for kings and emperors and the like to be assassinated, of course; as Live Science reports, one of the most popular theories concerning Alexander's unexpected death was poisoning. But there's a new theory that is even crazier: As Smithsonian Magazine notes, Alexander the Great may have suffered from Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS), an incredibly rare autoimmune disease that attacks the nervous system. GBS matches every symptom Alexander is reported to have experienced, including the creeping paralysis that left him mute but still rational. GBS can be contracted from bacteria that Alexander could have easily encountered while trooping around the world killing his future subjects.

Even crazier, as History notes, GBS might also explain why his body didn't decompose: Because maybe he wasn't actually dead yet. GBS may have depressed his respiration to the point that his breathing wasn't obvious. Which means the greatest military mind of the ancient world might have been very much alive when he was declared dead.

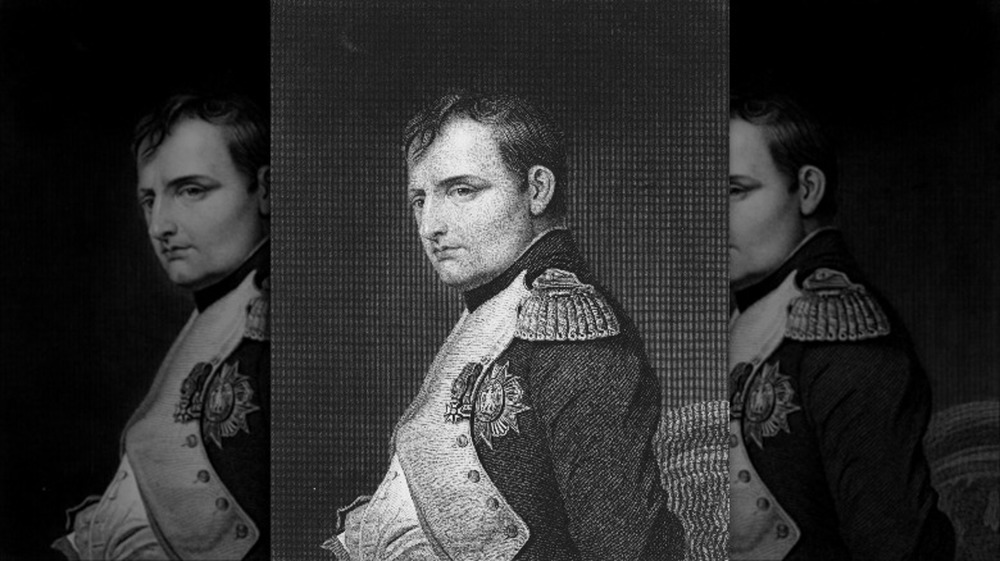

Napoleon: Arsenic poisoning

Napoleon Bonaparte was a military and political genius—it took no fewer than six coalitions of his enemies to eventually defeat him and pack him off to prison on the island of Elba in 1814. Less than a year later, he escaped, marched on Paris, and had one last bit of excitement before being defeated one final time at Waterloo—by a seventh coalition of European powers. Imprisoned again, this time on the island of Saint Helena, as ABC News reports he was often ill and died less than seven years later.

The official cause of death was stomach cancer—but there was one odd detail: When Napoleon's body was moved in 1840, it hadn't decomposed much at all. As the Seattle Times reports, this led to the theory that Napoleon had actually been poisoned using arsenic. Arsenic was a common poison at the time because it's undetectable, and it's a powerful preservative, which could explain why Napoleon's body stayed so fresh. His captors were terrified of a repeat of his 1815 escape, so quietly killing him might have seemed like a good idea.

As National Geographic notes, most medical experts think cancer is a much more likely explanation. But Napoleon's remains have been shown to contain high levels of arsenic—so it's possible he died of both cancer and poisoning.

Yasser Arafat: Polonium

When Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat died in 2004, he was 75-years-old and according to The New York Times had been the target of Israeli assassination teams for decades. But initially his death seemed to be the result of a sudden illness, possibly influenza. He was briefly and intensely ill before being transported to France for treatment. He fell into a coma and died about a week later of a massive stroke.

But as The Washington Post reports, his wife, Suha, believes Arafat was poisoned using the radioactive material polonium. A 2013 investigation found some evidence that this might be the case—a lot of Arafat's possessions were found to be slightly more radioactive than they should have been. Which is to say, radioactive at all.

As CNN reports, polonium-210 is not terribly dangerous as long as it remains outside the body. It emits alpha particles, which are so weak they can't even pass through a sheet of paper. But once inside us, they get into our bones and organs, and their effects look like end-stage cancer very quickly. That fits perfectly with the sudden illness Arafat suffered, which also resembles known cases of polonium poisoning like Alexander Litvinenko in 2006. Polonium poisoning has become very popular for political assassinations because it's very difficult to detect and very effective at killing people.

Pope John Paul I: Murder

Popes were once incredibly powerful princes, but these days we regard them more as good-natured grandfather types. Popes haven't been very controversial since that time one sort of, kind of supported the Nazis.

Popes also tend to be very, very old men, so when one dies it's usually not considered too shocking. But when Pope John Paul I died of a heart attack in 1978, he'd only been pope for 33 days and he was just 65-years-old. As Crisis Magazine reports, there's a robust theory that John Paul I was murdered—and it is wild.

As InsideHook notes, the Vatican took steps to keep John Paul's cause of death a secret. Reports were inconsistent, making it unclear where the pope was found, or who found him, and the Church refused to allow an autopsy. This led to speculation as to the possibility of foul play—and the most compelling theory has to do with the Vatican Bank, long suspected of dubious investment practices, money laundering, and outright theft. In fact, the Vatican Bank and the apparent gangland murder of "God's Banker," Cardinal Roberto Calvi, inspired the plot of the film The Godfather Part III. Many still believe that Pope John Paul I was killed because he'd stumbled onto the bank's unlawful activities and planned to do something about it.

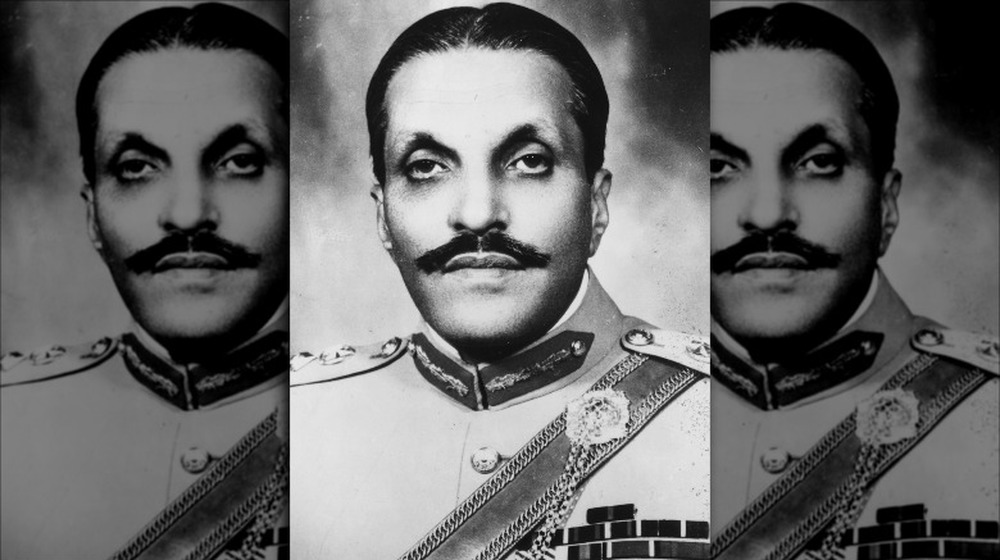

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq: Assassination

Pakistan can be an exciting place to live—as long as you consider "exciting" the right word to describe a place where tensions with India are always threatening to boil over, society is roiled by religious conservatism, and a former president can be indicted for conspiracy to murder a former prime minister.

In 1988, however, things were much worse in Pakistan because it was ruled by a military dictatorship under General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Zia was ostensibly president but had seized power during a military coup. Then in 1988 he traveled via plane with the U.S. ambassador to watch a demonstration of U.S. M1 tanks. On the way back, the plane crashed, killing everyone on board. As OZY notes, Zia's death led to the first free election Pakistan had in years, ultimately transforming the country. And many people suspect Zia was assassinated.

As The Guardian notes, the suspects range from Russia to Israel to the CIA (naturally). According to the Los Angeles Times, most of the theories focus on a crate of mangoes loaded onto the plane just before it took off. Some suspect a bomb was hidden inside—though no evidence of a bomb was found at the crash site—or that the fruit was coated with a substance that emitted poisonous fumes.

Benito Mussolini: Accident or assassination

Benito Mussolini ruled Italy as a literally fascist dictator from 1922 until 1943, when he was deposed and arrested—but he was rescued by the Nazis before he could be handed off to the Allied forces. When the war finally ended, Mussolini made a run for it but was captured, and after a hasty tribunal he was executed by firing squad. His body was transported to Milan, where citizens kicked and spat on it, then hung it upside down from a gas station roof.

This always seemed kind of sketchy, and as Yesterday Channel reports there's reason to believe it didn't happen this way. Urbano Lazzaro, who actually arrested Mussolini and his mistress, Claretta Petacci, claims that Petacci tried to grab one of the guards' guns to make an escape, and the two were shot more or less accidentally. The execution was staged because everyone worried the people would be dissatisfied with the truth.

Even crazier is the theory that Mussolini was actually assassinated—on the orders of Winston Churchill. According to The Independent, Churchill had betrayed his allies by secretly negotiating for peace with Italy, and feared exposure. So he ordered the Italian dictator killed to stop him from revealing the truth. There's no proof of this—but, of course, there wouldn't be.

King William II: A staged accident

Most people can name at least a few kings and queens of England, and a couple are pretty widely well-known: Both Elizabeths, for example, or Henry VIII. An exception to that is England's second king: William II, also known as William Rufus. The son of William the Conqueror inherited the throne when his father died in 1087, and he reigned for 13 years, avoiding disaster but achieving little. He isn't mentioned much in the modern day except for the manner of his death.

According to historian Emma Mason, William went hunting with his younger brother Henry and several nobles, including Walter Tirel. William distributed the arrows he had brought among his friends, and set off with Tirel to hunt stag. Seeing their quarry, the king shot and missed, calling out to Tirel to take his shot. Tirel somehow managed to sink his arrow directly in the king's chest, killing him instantly.

An accident, perhaps—as Unofficial Royalty notes, hunting accidents like this were really, really common in those days, and several of William's relatives had died that way. But as the BBC reports, his brother Henry wasted no time claiming the throne for himself, and many suspect that Tirel—who fled the scene, and then the country—murdered William on Henry's behalf.

King Charles XII of Sweden: Battlefield execution

There was a time when Sweden was a well-oiled military machine. In fact, King Charles XII, who reigned from 1697 to 1718, spent most of his life fighting on the battlefield. This wasn't entirely his fault. As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, when he ascended to the throne at the age of 15, Russia, Denmark, Poland, and other regional powers formed a coalition and attacked Sweden, hoping to overwhelm the young king.

But as Daily History reports, Charles turned out to be something of a military genius. By 1706 he had knocked everyone but Russia out of the war—and Russia sued for peace. Charles rejected the idea and, as noted by the BBC, launched an invasion of Russia that went the way every invasion of Russia goes—very, very badly. Which is also how things went for Sweden.

By 1718, Charles' popularity in his kingdom had plummeted. His insistence on endless war had exhausted his people. So when he was shot in the head on the battlefield that year, foul play seemed likely. Modern forensic investigations have found that the shot probably came from his own side of the battle, and a man named André Sicre, who was secretary to the man who would succeed Charles as king, confessed to the murder while suffering a terrible fever.

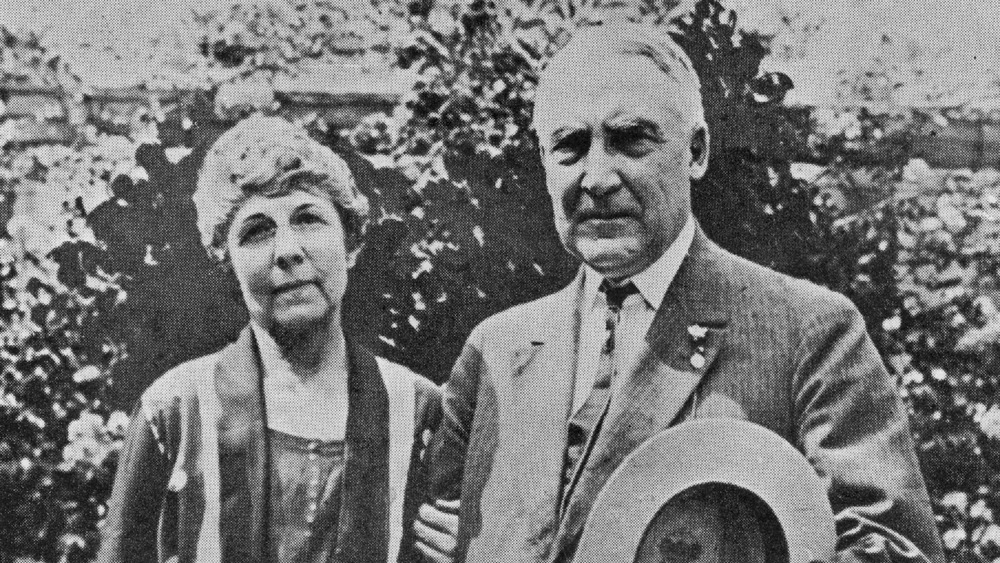

Warren G. Harding: Poison

Eight of our 45 presidents have died while in office—four due to assassination. Or maybe that should be five, because there's a theory that our 29th president was poisoned by his wife. As The Mercury News reports, there's a lot of suspicion that Warren G. Harding might have been murdered by Florence Harding.

There's many reasons to like the theory. For one, Warren Harding wasn't only one of our worst presidents (CBS News ranks him as fifth worse all-time), he was also a pretty terrible husband. As detailed by Politico, Harding had numerous mistresses and fathered an illegitimate child. Florence remained married to him for appearances.

Warren's death came in the midst of a lengthy and exhausting trip around the country, and it's possible Florence was poisoning him slowly the whole time. In a San Francisco hotel room, he was alone with Florence when she suddenly raised the alarm, and Warren was found dead in bed. The doctors issued several causes of death before settling on a heart attack, but Florence refused to allow an autopsy. The hotel president—summoned by Florence and accused of killing Warren with the hotel's terrible food—claimed that a glass of water next to the president's bed smelled "noxious," but Florence grabbed it and poured it down a drain.

Emperor Jovian: Indoor cooking

Being Roman Emperor was a pretty terrible job, because the moment you were proclaimed Augustus people were plotting to kill you. Some emperors made it easier than others. Jovian, for example, ruled for just eight months from 363 to 364. He'd been a senior staff member to Emperor Julian, who'd led his army into modern-day Iraq, suffered a wound, and promptly died. As noted by historian Ilkka Syvänne, the army tried to get a guy named Saturninius Secundus Salutius—the highest-ranking Roman officer around—to be emperor, but the old man refused. While the officers huddled, trying to decide who to nominate next, a bunch of soldiers proclaimed Jovian emperor—and everyone else just went along with it despite almost certainly having no idea who he was.

Jovian was a Christian fanatic, and his main impact as emperor was to refute Julian's paganism and make Rome a Christian empire once and for all. Other than that, he's mostly known for the way he died. While still traveling to Constantinople to claim the throne officially, he was found dead in his room one morning, untouched. Theories abound; historian Warren Treadgold writes that many suspect a charcoal heater suffocated the emperor, though History Collection notes some believe it was poisonous mushrooms.

Prince Edward and Prince Richard: Secret execution

Known as "The Princes in the Tower," Edward and Richard had the bad luck to have a healthy claim to the throne of England just when their uncle, Richard III, usurped it. According to the BBC, it all started when Edward IV, who had just established some stability in the country after the Wars of the Roses, died unexpectedly. Although his son was officially proclaimed Edward V, his uncle Richard, the Duke of Gloucester, got himself named his nephew's protector. Richard placed Edward in the Tower of London, and soon after sent Edward's younger brother, Richard, to join him. The boys were never seen again, they were declared illegitimate, and a few weeks later Richard was crowned king.

It seems very obvious that Richard III, knowing his claim to the throne was tenuous, murdered the young boys. But as noted by The History Press, many people theorized that the boys were smuggled out of the Tower and lived on under assumed names, waiting for their chance to claim the throne. Many of their relatives behaved in ways that implied they did not believe the king was a murderer.

On the other hand, as History Extra notes, the new king didn't have to explicitly order their deaths: Plenty of people would have been happy to kill them just to curry favor with the new king.