The Untold Truth About Madams In The Wild West

Move over, Miss Kitty. The endearing harlot of the 1950s- and 60s-era television show Gunsmoke was a clean enough representation of madams in the old Wild West. Rarely, however, does Hollywood portray these women in a truthful light. Just take a look at Hornet, which lists ten films illustrating how the movie industry fails to portray the gritty business of sex work as it really was, and is. Even as film studios began employing stars like Greta Garbo to portray prostitutes during the 1930s mandates like the Hays Code, says NPR, studios also employed strict rules regarding moral conduct and "correct thinking" when writing and producing movies.

William Hays, the brainchild behind the Hays Code, would have been shocked to learn that the madams who ruled over the sex trade during the 1800s and early 1900s were more than just love goddesses. These women were actually businesswomen who ran brothels of various classes wherein soiled doves sold sexual favors for money. Each madam had to make the most of her services while staying on the right side of the law. These busy ladies had a lot on their plate — they were responsible for running an honest house, making sure their employees were healthy and disease-free, paying fines, making monetary contributions to the cities in which they operated, and much more. Read on for the untold truth about madams in the Wild West.

Why women entered the sex trade in the Wild West

During the 1800s, jobs for women were extremely scarce. Ohio History Central confirms that women in general were expected to work in the home performing domestic chores, growing food, and caring for their children. Those who ventured into the working world were often relegated to roles like schoolteachers (making just over $80 a year, according to QEMA), laundresses, clerks, and factory workers. In the latter field, women were subject to "awful pay and working conditions." A job in the prostitution industry, however, gave women independence and a way to make good money. An example is the celebrated courtesan Ah Toy in San Francisco during the 1850s. Writer Mirya Rose Holman says that men paid an ounce of gold just to have a look at her.

Of all the classes of prostitutes — streetwalkers, crib girls, common prostitutes, and even parlor house girls — being a madam was the most lucrative. Some like Salida, Colo., madam Laura Evens "loved to sing and dance and get drunk and have a good time," according to writer Emma R. Marek. Alternatively, Denver madam Mattie Silks explained that being a madam "was a way for a woman in those days to make money, and I made it." Author Heather Branstetter submits that the sex industry was indeed a needed service and even kept sex crimes at a minimum.

The three classes of madams

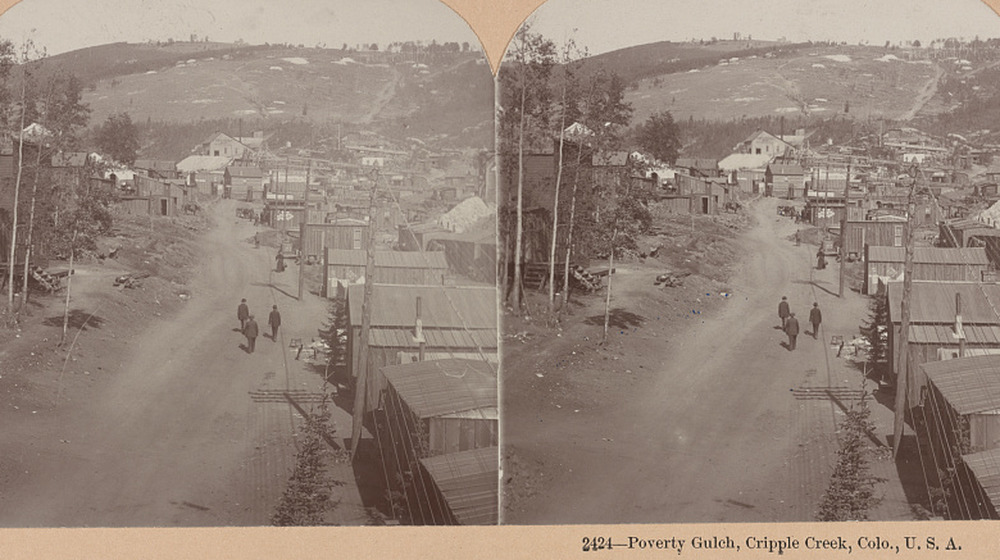

In general, madams fell into three general categories. Some, like Helen Harbin of Carson City, Nev., served as mere landlords over a brothel property. According to the Las Vegas Sun, Harbin inherited the brothel after her husband died. Although she never worked in the sex industry, she rented out the house to various madams. Likewise, madam Laura Evens confirmed that when she began her career in Leadville, she rented a bordello from another madam, Lou Bunch. Later, Evens ran her own parlor house but hired Lillian Powers to run her cribs (small, two-room apartments) in Salida — after Powers was run out of Cripple Creek by her own landlord, a French woman known as Leo the Lion.

Evens, Bunch, and thousands of others often ran their own brothels. These were not common houses of prostitution attached to a saloon. Rather, the best madams operated out of fancy parlor houses where, according to Emma Marek, the employees were "boarders" who lived and worked in the same house. The ladies paid about half of their earnings to the madam for room and board and were generally allowed to keep their tips. Prices at a parlor house could be anywhere from $10 per customer in the primitive mining towns to $50 in larger cities like Seattle and San Francisco.

A good madam was a good businesswoman

It took business savvy for madams to succeed. As Legends of America explains, a good parlor house offered the best in liquor, cigars, and talented women who could sing or play piano. The more services a madam offered, the more money she made. Many madams acquired enough cash to purchase real estate and further their wealth. TruTV's Adam Ruins Everything further explains that madams contributed heavily to the economies of their towns by paying monthly fees and fines, business licenses, and other monetary necessities in order to appease the law and stay in business. They also helped others.

The bottom line, says F Yeah History, was that madams aspired to make sure their towns did well so they could build their own business empires. Many, like South Dakota madam Dora Dufran, worked their way up from being a common prostitute to become successful madams, says Recollections. Most importantly, madams often served as surrogate mothers to their girls while making sure they were successful. Denver madam Jennie Rogers, says author Chris Enss, actively shopped for her employees' gowns herself and subtracted the cost of the dresses from their pay. Portland, Ore., madam Stella Darby even taught her girls how to save their money so they could eventually leave the prostitution industry.

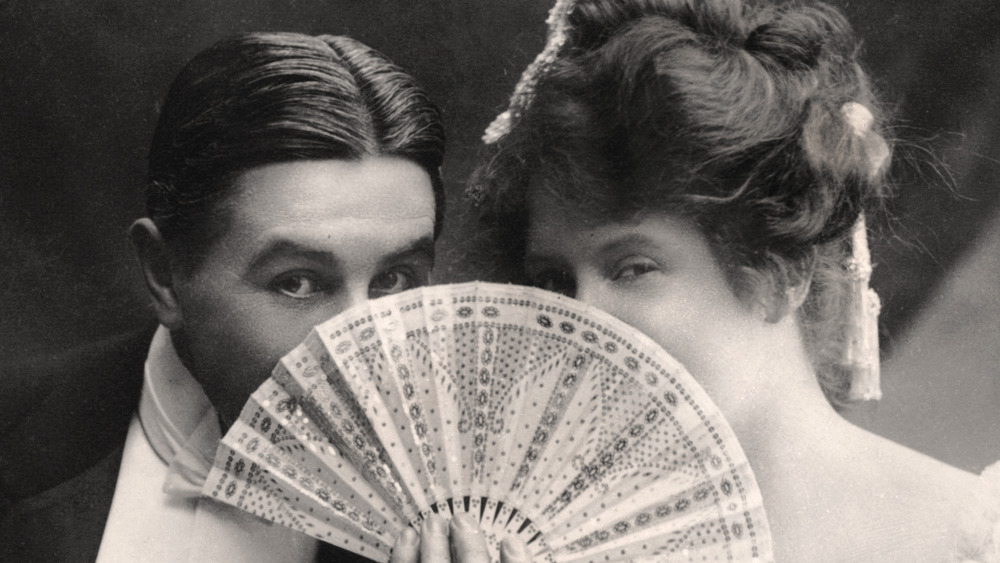

Clients sometimes became ceremonial husbands

One of the best parts of being an upper-echelon madam was meeting the often wealthy clients who came through her parlor house. Madams sometimes married these otherwise upstanding men, who could in turn protect them from the law and raise their reputations to that of respectable wives. A classic example is lawman Wyatt Earp, whom Legends of America confirms was the "common law" husband of prostitute Mattie Blaylock and later, Josephine Marcus. Arizona madam Gabrielle Dolly Wiley married several times, nearly always to men who could assist her in her business matters.

Tessie Wall, one of San Francisco's most famous madams, took great pains to marry one of her investors, Frank Daroux, according to Trivia Library. Granted, the marriage was not always ideal, but Daroux's influence on the underworld included protecting the madam. While Daroux did not like it that the public knew who he was married to, society often simply chose not to acknowledge the illicit wives of certain men. The two later divorced much to Tessie's disappointment. In fact, she actually shot him once, claiming, "I shot him because I love him, God damn him!" Daroux lived.

When another prominent man, Frank Connelly, died in Salt Lake City in 1884, his obituary neglected to mention that his death occurred at the brothel of Kate Flint — and nobody knew the two were married until "Mrs. D.F. Connelly" published a card of thanks in the Salt Lake Tribune.

Good madams versus bad madams

Author Clark Secrest (per Millerksweetheart's Blog) probably said it best — "A good Madam exercised discretion in handling both police and clients." It was the duty of a madam to keep her girls safe, away from harm. Most madams, verifies writer Megan Sharpless, hired body guards (sometimes referred to as pimps) to "protect the women from violence, rape, murder, and theft." Room and board at a proper brothel often included laundry, chambermaid services, meals, and other comforts. But the madams also were in the business of making money, always taking a share of their girls' profits while making sure their brothels served as homes to the girls. Notably too is that the money madams demanded from their girls often resulted in the ladies being indebted to the house and prevented them from leaving for a job elsewhere.

Other madams exhibited violence towards their girls. A classic example is "Leo the Lion," the drunken Colorado crib madam who rented to Lillian Powers but threatened her life in a jealous rage. Powers later became a prominent madam in Florence. In 1914, newspaper writer Julian Street happened to meet Leo in Cripple Creek. He described her as wearing an outfit "grotesquely juvenile for one of her years," and that she had "brown and stringy" hair. And in Montana, says author Nan Parrett, madam Mary Gleim sometimes beat her employees, cheated them at every turn, and failed to look after them like a proper madam should.

Madams helped develop their towns

It took a lot of money to run a brothel, even more to run a parlor house. The Sun points out that because prostitution in the Old West was largely illegal, madams regularly paid monthly fines and fees in order to stay open. Those brothels serving alcohol were usually required to purchase liquor licenses. Liquor dealers, grocery stores, furniture stores, dressmakers, music stores, pharmacies, and physicians also made money off the skin trade. Done right, writes Emma Marek, cities could make a lot of money from the industry. In just three months during 1887 for instance, the Cheyenne City Jail in Wyoming made $1,028.50 off its wayward women — over $28k today.

A red-light district also could become one of the "social centers of their areas." Park City, Utah, madam Rachel Urban prided herself in this, and when officials tried to shut down the red-light district, she approached a local mine superintendent, reports the Park Record. Urban explained that without her business miners were likely to look for love in other towns, leading to increased absenteeism and less production for the mine. Urban's clients indeed enjoyed her services, particularly the annual Christmas parties she threw with every one of her girls in attendance. Then there was Seattle madam Lou Graham, whom F Yeah History confirms used her money to help save legitimate businesses and banks during a depression.

How madams worked with city officials

How does one conduct an outright illegal business? By getting in the pockets of authorities, that's how. Most madams worked with city officials to make sure both their brothels and the city did well. As F Yeah History puts it, the women "weren't just there for the money, they wanted to make a difference." An astute madam knew how to work the courts in her favor, says Emma Marek, and was not beyond bribing officials with money or gifts as a means of maintaining a working relationship with them. Everybody knew, for instance, that members of the Colorado legislature were accustomed to visiting the brothel of Jennie Rogers each day after work. The men knew that the madam would not reveal what they discussed at her place, out of hearing range of their adversaries.

Another Colorado madam, Mae Phelps, actually helped found and fund an extension of the city of Trinidad's trolley line to assure it ran by her parlor house in the red-light district. Perhaps the most blatantly public arrangement between a madam and city officials was the hiring of Utah madam Dora Topham to construct and run a special red-light district in Salt Lake City, the Stockade, during the early 1900's. Measuring a full city block with parlor houses, cribs, and other men's entertainment, the Stockade was one of the only legal, city-approved brothel districts in the West for its time.

Madams contributed heavily to charities

Most madams recognized that if their towns did not do well, their business would not do well. The Bozeman Daily Chronicle in Montana reports that the town's madams often became wealthy enough not only to buy ranches and build houses but also to "open shops and give out loans and mortgages." Monetary acts of kindness were quite common, notes the Daily Mail. And although the ladies sold sex for a living, their love extended to children who might need shoes or winter coats and other causes. New Mexico madam Sadie Orchard even gathered donations for a church and helped nurse the sick during an epidemic.

Indeed, many were the madams who were recognized for their kindnesses. In Virginia City, Nev., Julia Bulette (pictured) assisted the fire department so often that they gave her an honorary helmet. When Carson City madam Cad Thompson died in 1897, the Morning Appeal newspaper praised her as having "possessed many sterling qualities. She was kind and charitable and her word was as good as gold in all of her dealings." And in Montezuma, Colo., madam Ada "Dixie" Smith was known to buy canned milk by the case and beef extract to feed the cats and dogs around town.

Many madams had soft spots for children

Delancy Place submits that many harlots "were products of dysfunctional families or had suffered abuse as children." Perhaps that is why a surprising number of madams understood the plight of the West's offspring and exhibited love for them. Legends of America correctly surmises that due to primitive forms of birth control in the 1800s, a number of "painted ladies" eventually had children either before or during their careers. The outcome was not always pleasant. Montana's Bozeman Daily Chronicle tells of one woman who passed her "unwanted baby" to a train conductor, asking him to "drop the child off at the next town."

Alternatively, Dora Topham raised her daughter Ethel in her private home atop her parlor house. Wealthy madams often sent their children away to school. But raising a kid in the brothel world occasionally ended in tragedy. In 1878 for instance, the Sacramento Daily Union reported that Cad Thompson's son Henry committed suicide at her brothel. Also, not all women were allowed to keep their children. When Colorado madam Molly May died in 1887, her obituary noted she had struggled against the authorities to keep her adopted daughter. Likewise, when madam Mary Jones found a baby on her doorstep in Pueblo and adopted it, the courts took it away because she was "not a proper person" to keep the child.

Some madams maintained familial relationships

Colorado history buffs are well familiar with madam Pearl DeVere, who died in Cripple Creek in 1897. When her sister arrived from out of town and found out that DeVere had been a madam, she refused to claim the body, according to Colorado Community Media. DeVere was buried by the kindly townspeople instead. On the other end of the spectrum was fellow madam Laura Bell McDaniel of Colorado City. Until her death in 1918, McDaniel maintained an open and loving relationship with her family to the extent that her mother, sister, and daughter lived just blocks from her brothel.

There is more evidence showing that some madams and their families remained close. When Wichita, Kan., madam Dixie Lee died, says the Oklahoman, she left her fortune to her preacher father. In Pueblo, Colo., in 1901, says author Chris Enss, Rose Libblin's brother took great pains to rescue his own sister from the demimonde so he could provide "a respectable living with himself and his sister." And in 1914, the Park Record in Utah reported that madam Rachel Urban immediately left for her hometown of Cleveland upon hearing that her sister's husband had died. She was, the paper said, expected to be gone for several months.

Madams had both sad and happy endings

As one might guess, madams of the West ended their careers a variety of ways. When Virginia City, Nev., harlot Julia Bulette was robbed and murdered in 1867, the whole town turned out to see her killer hang. Others committed suicide — in 1879, after losing the last of her money, gambler and brothel queen Eleanor Dumont was found dead with a suicide note outside of Bodie, Calif., says the Vintage News. Salt Lake City madam Helen Blazes became despondent in her old age, especially after a thief broke into her home and tied her up. The Salt Lake Telegram reported in 1932 that Blazes' maid found her lifeless body on the bathroom floor, and a note explained the woman was "through with life."

Other madams grew into sweet little old ladies, often with nobody the wiser as to who they had once been. In 1922, Albuquerque madam Lizzie McGrath died from a stroke in her home. When Diamond Lil Davenport grew too old to take care of herself, says Legends of America, her friends took her to a Washington nursing home. Davenport's famous diamonds were "sold off one by one to pay for her care," and when the money was gone, she was taken to a nursing home where she died at age 93 in 1975. Just a month later, Dolly Arthur of Ketchikan, Alaska, also died in a nursing home, says Diary of a Mad House Crisis.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Madams are getting the honors they deserve

These days, madams are finally getting the credit they deserve for their part in the growth of the American West. There was a time when many women of the night, such as Rosa May and Lottie Johl of Bodie, Calif., were not permitted to be buried inside the fence of the cemeteries where they died (Johl's husband fought the city, and she lies within the cemetery today). Even those who were allowed a proper burial were often left without a tombstone to mark their grave. Colorado madams Blanche Burton and Marie LaFitte, however, are two women who have had tombstones donated to their resting places in recent times.

Thankfully, today the history of prostitution in the West is being preserved by a number of brothel museums in various states. The oldest of these is madam Pearl DeVere's Old Homestead in Cripple Creek, which was built in 1896 and became a museum in 1958. Following her death in 1975, Dolly Arthur's house in Ketchikan also became a museum and features her personal effects and furnishings. Shortly after it closed in 1988, the Oasis Bordello Museum in Wallace, Idaho, began giving tours, which include the madam's bedroom. At the Dumas Brothel Museum in Butte, Mont., visitors are treated to three floors of the former parlor house, which featured an amazing 43 bedrooms. Most recently, the Brothel Deadwood in South Dakota also opened for tours. Congratulations, ladies, you've come a long way.