Moments In Canadian History That Went Horribly Wrong

Canada seems like a calm, peaceful kind of country. With a population about one-tenth of the United States, when you think of Canada you think of charming Mounties with their silly hats, their improbably handsome prime minister, or maybe their access to universal healthcare. The country just seems like a sedate, happy place. Canadians are even world-famous for their politeness, which is truly a shocking thing to be world-famous for in the 21st century.

But Canada has a history just like any other country. And that history is surprisingly dark and violent at times. The country has made some pretty terrible decisions with some seriously negative consequences — some of which are still reverberating through modern day Canada. The closer you look at the country's history, the clearer it becomes that Canada has just as many problems as other nations, many of which stem from disastrous moments stretching back decades or even centuries.

So next time you've got cause to consider our neighbors to the north, remind yourself that while Canada seems like the most polite nation on Earth and enjoys universal healthcare, it's not perfect. And if you need proof of that, here's a list of moments in Canadian history that went horribly wrong.

The expulsion of the Acadians

Canada was originally populated by a variety of Indigenous people who were systematically pushed aside. The French and the British competed to claim territory in what is modern day Canada, with France ceding most of its claim to Great Britain in 1763 after the Seven Years War (sometimes referred to as the French and Indian War in American history books).

War does funny things to people. The struggle between Britain and France stretched back many decades, and as noted by the New England Historical Society the British had taken an area called Acadia back in 1710, leaving them with a largely French-speaking population to manage. When the Seven Years War broke out, the British worried about the Acadians and their loyalties. Not only were the Acadians defiantly French, they were also mostly Catholic. So in 1755 the British thought it prudent to require the Acadians to take an oath of loyalty to England — which the Acadians robustly refused to do.

According to the National Post, this led to what many believe should be defined as a genocide or an attempt at ethnic cleansing — the forced removal of more than 10,000 Acadians from the area. They were initially sent to the 13 North American colonies, and many were later forced onto ships headed for Europe. They weren't treated well, and as many as 5,000 perished from disease, starvation, or disasters at sea.

Grabbing Rupert's Land

Canada was a collection of distinct British colonies until 1867. Immediately after forming, Canada began acquiring more territory and incorporating it into its dominions. One of those acquisitions was an area known as Rupert's Land, which, as noted by the encyclopedia Britannica, was populated primarily by the Métis, descendants of French and English settlers who had taken Indigenous wives. The French-speaking Métis were seriously concerned that their land rights wouldn't be respected. The Canadian government made exactly zero effort to reassure them. So, led by a man named Louis Riel, the Métis mounted an armed revolution and set up a provisional government headed by Riel.

The rebellion went well for the Métis at first. Then, as noted by historian Jennifer Reid, Riel made an incredible mistake when he allowed a settler named Thomas Scott, who refused to support the rebellion, to be executed. This turned popular opinion against the rebels, and their negotiating leverage was so reduced that the territory they were given (modern day Manitoba) was very small, and their rights were never respected by subsequent Canadian governments. Riel was eventually executed for treason, and the Métis largely emigrated west despite their supposed victory. The whole episode exacerbated distrust between French- and English-speaking Canadians, driving a wedge between the two groups that can still be felt today.

Canada enters World War I

Canada's decision to enter World War I was a real blunder in terms of psychological damage to the country. On the one hand, the war had a predictable effect in boosting Canada's economy as the military machine prompted new factories to spring up almost overnight, fueled by the need to build up Canada's fighting forces quickly. But as Maclean's reports, the war effort also further split English-speaking Canada and French-speaking Canada. The possibility of conscription was vehemently opposed by the French side and supported by the English. The French-speaking population was accused of shirking their duty (voluntary enlistment in the army was much lower in areas of French-speaking Canada like Quebec). The 1917 election was an almost perfect split between the two voting blocks, with the victorious pro-draft English side widely suspected of manipulating the vote to win.

Canada suffered huge losses in World War I — more than 60,000 Canadians died in the conflict. And as noted by The Globe and Mail, it also experienced one of the worst disasters in its history when a Belgian relief ship hit a French munitions ship in Halifax, causing the largest man-made explosion in history before the atom bomb. The fire nearly destroyed the city entirely, killed 1,600 people, and wounded 9,000 — in a city of just 50,000. The decision to enter the war was in every way a disaster for Canada.

Choosing the Ross Rifle

The decision by the Canadian government to use the Ross Rifle in World War I was catastrophic. According to The National Interest, in 1901 Canada tried to buy 15,000 Lee-Enfield Mark I rifles from Great Britain. But Great Britain was switching over its own armies to the new rifle and had supply shortages, so the sale was denied. That irritated the Canadians, and a movement to design and manufacture their own weapon gained traction. The result was the Ross Rifle, which was found to be accurate in testing.

The gun might have been accurate under sniper conditions, but the Ross turned out to be a pretty awful weapon for trench warfare. As reported by The National Post, Canadian soldiers referred to the gun as the "Canadian club" in a reference to its sole use as a combat weapon. In fact, it's widely regarded as one of the worst combat rifles ever deployed. It was too long for trenches, too heavy, and had a bad habit of ejecting the bayonet when fired. It also jammed extremely easily, and the action bolt on early versions was so poorly designed it often simply fell out of the gun. There's little doubt thousands more Canadians died as a result of choosing to use the Ross.

Canada passes the Indian Act

Canada is a country where European colonists smashed into existing native populations and did everything they could to move, destroy, or absorb them. The most egregious example of the latter effort is the Indian Act, a racist law passed in 1876 and still in effect today.

As explained by National Magazine, the purpose of the law was to force Indigenous First Nations people to integrate into the Euro-centric Canadian culture. This was to be accomplished by legally defining who was considered "Indian," then by controlling the Indians living on reservations. The idea was to make being "Indian" less attractive than being "Canadian," allowing Canada to keep up its promises to the First Nations people while slowly and peacefully eliminating them.

As noted by Global Citizen, however, this hasn't really worked out. Instead of encouraging First Nations people to give up their identity, it's simply stripped them of their rights. Most Indigenous people don't own their land, the decision about whether their children are considered "Indian" or not is up to the government, and often lack authority to make their own community decisions. The law is increasingly viewed as a relic of an earlier age and has been revised several times to try to make it less horrifying, but it remains on the books because it's so deeply embedded in the law — removing it wholesale would be almost impossible.

Crushing the Winnipeg General Strike

In the early 20th century, the city of Winnipeg was languishing. An economic downturn left the city in shambles, with high unemployment and almost zero investment in infrastructure or social services. The working class population was already suffering when, as noted by Jacobin Magazine, Canadian World War I veterans finally managed to come home in 1919. Their conclusion was that rich business owners had profited off the war at the expense of the workers while they risked their lives in Europe.

In May 1919, the leaders of Winnipeg's labor unions combined their efforts and organized a massive strike that saw nearly 30,000 workers simply walk off their jobs. As the History Museum notes, this paralyzed the city, prompting the government to get involved — which meant breaking the strike, violently.

That decision was a terrible one. The police, supplemented by units of "special police" with baseball bats and other weapons, unleashed brutal violence on the strikers, killing several and arresting the men they'd identified as the leaders of the strike. Things got so bad the army was called in to patrol the streets. But the authorities failed to get convictions in court, and while the strike was broken, the government's harsh response has made the strike legendary. Far from destroying the labor movement, the strike has become a major inspiration for organized labor today.

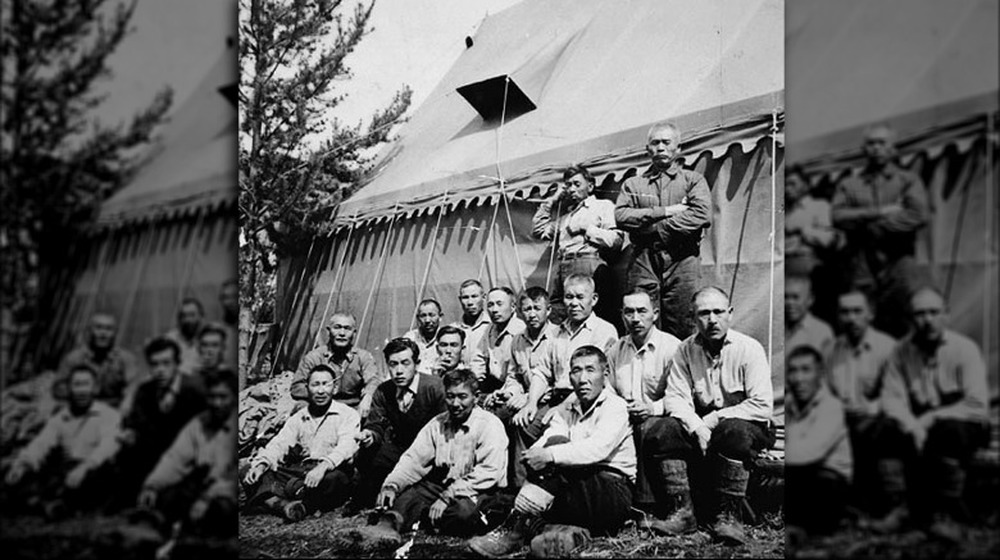

Canada interns their Japanese citizens

Canadians are just as prone to racial panics as Americans, unfortunately. In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Canada reacted very similarly to the United States in its treatment of people of Japanese descent living inside its borders. Which is to say they made a series of awful decisions motivated by racism, fear, and a general disregard for people's fundamental human rights.

In fact, as noted by The Japan Times, the experience of Japanese Canadians in World War II was in some ways even worse than that of their American cousins. About 21,000 Japanese living in Canada were forced to leave their homes and move into internment camps. Worse, according to Atlas Obscura, their property was seized by the government and often sold off without their consent. Their freedom was restricted long after the war ended, with many forced to return to Japan and those that chose to remain in Canada forbidden to live in certain areas. Those who remained often had nothing left of their former lives and had to completely start over.

Japanese organizations agitated for years after the war, and in 1988 succeeded in getting a formal apology from Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Each victim of the policy was awarded $21,000, and funds were established to fight racism and to help the Japanese community in Canada.

Attempting the Dieppe Raid

Canada was on the side of the Allies in World War II and participated in several key engagements that helped turn the tide against fascism. Unfortunately, they also chose to participate in one of the biggest disasters of the war, the Dieppe Raid.

According to the BBC, the raid, code named Operation Jubilee, was designed to test the feasibility of an amphibious landing at the port of Dieppe in northern France, held by the Nazis. In August 1942 about 6,000 soldiers (mostly Canadian) were put ashore along with an armored force. The plan was to destroy German fortifications and determine whether a larger landing would be possible. The expectation was that a successful raid would boost morale, proving the Nazi war machine wasn't unbeatable.

And that might have worked ... if the raid had been successful. Unfortunately, as made clear by historian Robin Neillands, the Allies botched the planning. They didn't provide enough planes and boats to establish air supremacy and support. As a direct result, the Canadian infantry found themselves trapped on the beach with the mired tanks, pinned down by relentless German fire. The end result was one of the worst military disasters of World War II, with nearly 1,000 soldiers killed and an astounding 2,000 taken prisoner.

Canada passes the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Act

There was a time when the subject of universal healthcare was pretty controversial in Canada. In fact, when Saskatchewan introduced the first law of its kind in 1962, the roll out was handled so badly every doctor in the province went on strike.

As explained by Vox, the idea of universal, single-payer healthcare was met in Canada with the same arguments that Americans make against the idea — it's too expensive and would take crucial medical decisions away from doctors and let them be made by bureaucrats. Physicians in Saskatchewan were uniformly opposed to the idea, arguing that it would reduce the quality of care they would be able to provide. But the province's premier, Tommy Douglas, went ahead with the plan anyway, and on July 1, 1962, the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Act went into effect. A few hours later, every doctor in Saskatchewan walked off the job in protest.

The strike wasn't universally popular. The government brought in doctors from other provinces and even from the U.S. to handle emergency cases but refused to consider changing the law, keeping the chaos going. Eventually, a compromise was reached — doctors would be considered independent contractors but would go along with the single-payer system. That opened the door to the spread of universal healthcare laws all across Canada, but it almost failed immediately.

Canada fails to pass the Meech Lake Accord

Americans are often unaware of the tension between French Canada and English Canada. When Canada took the final step away from the British crown with a new constitution in 1982, Quebec initially tried to veto, leading to a battle in Canada's supreme court. Quebec lost, but tensions were high, and there were real fears that Quebec might make an attempt to break free and declare its independence from Canada.

As explained by the Canadian Encyclopedia, in 1987 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sought to gain Quebec's support for the new constitution and stabilize Canada by negotiating an agreement between the government and all ten provinces to modify the constitution. The agreement, reached at Meech Lake and named after that location, recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" and granted new powers to the provinces.

The success of the negotiation was shocking — no one had actually expected anything to come of it. After an initial round of public support, the agreement fell apart as each province voted on it in the ensuing years. Eventually the Meech Lake Accord fell apart and was never passed, driving a further wedge between Canada and Quebec and re-energizing Quebec's independence movement. But as The Record notes, over the next 25 years Quebec eventually got almost everything it had wanted anyway, making the chaos of the Accord's failure even less understandable.

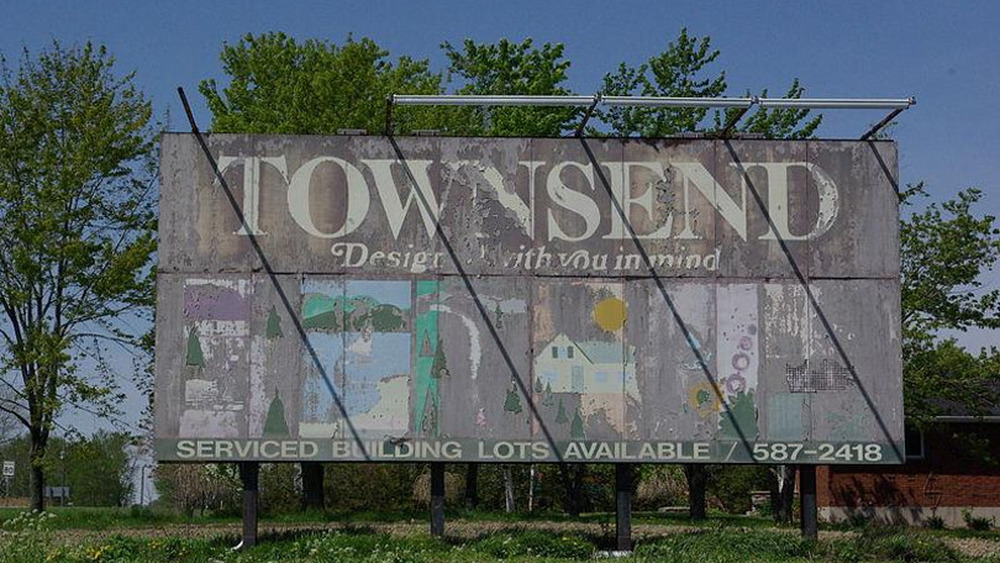

Building a town no one wants to live in

American President Ronald Reagan once said that "the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the government and I'm here to help." In the 1970s, the Canadian government provided plenty of evidence supporting that concept when it decided to build the city of Townsend.

As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, one of the biggest fears of the late 1960s and 1970s was overpopulation. Many theorized that in the next few decades the world's population would explode, draining resources and leading to the collapse of society. According to Spacing Toronto, in the early 1960s the Canadian government was worried that the city of Toronto was getting too crowded. Its solution involved building a new city in Toronto's suburbs called Townsend. It was meant to be home to about 100,000 people. According to SkyscraperCity, the good folks of Townsend would find work at an oil refinery, steel mill, and coal power plant at the nearby Nanticoke Industrial Park.

About 1,200 people did move to Townsend when the first buildings were put up ... and that's about it. Fifty years later, there are still fewer than 1,500 residents of Townsend, and much of it is a literal ghost town. In fact, the town sports exactly zero local businesses. Residents have to drive to other towns to do all their shopping.

Attempting to build a golf course on Indigenous lands

Canada's drive to insult and enrage its Indigenous population has continued into the modern age. Case in point — The Oka Crisis.

As reported by High Country News, in 1990, the local Mohawk community in Oka, Quebec, protested a plan to expand a condominium complex and a golf course onto land they claimed belong to the Mohawk people, land that included a tribal cemetery. When plans proceeded in spite of their protests, the Mohawk set up a camp and blocked an access road, then proceeded to ignore court injunctions ordering them to vacate the area. And Canada lost its mind.

The government sent thousands of police and soldiers to Oka, along with armored vehicles, fighter planes, and even naval forces. According to the Harvard International Review, the military seemed on the verge of negotiating a peaceful end to the crisis, but chaos erupted when a large number of protesters sought to leave the area at once, resulting in a crazy fire fight. In the end, the standoff went on to last 78 days and left a provincial offer dead — over a golf course.

The government "solved" the crisis by buying the land in question and canceling the golf course — but never gave the Mohawk an opportunity to buy it.