What It Was Really Like To Be A Court Jester

If there's one thing that people have shared throughout the ages, it's the need to lighten the mood every once in a while. Especially kings and queens. They've got it rough, after all, sitting up there on high, with the fate of all their subjects in their hands. What better way to get some distraction from things like war, famine, and plague than with a little slapstick juggling?

The pop culture image of the court jester is one of patchwork clothes and bells, cheesy jokes, and pratfalls. But it turns out that the position was about much more than just being a goofball. Anyone who might aspire to be a court jester would have to be more than just funny, they'd have to be the kind of witty — and charming — that would keep their head on their shoulders. They'd also need to be able to multitask, fulfill other roles within the household, and be very good at ducking, dodging, and escaping. What does that mean? Let's talk about what, exactly, it was like being a court jester in ye olde times.

Being a court jester was a deadly old profession

The court jester has been around for a long time, and according to the Boston Lyric Opera, there's mentions of court jesters going all the way back to the Sanskrit texts in ancient India, and there's even mention of a court jester in the writings of a Sixth Dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh, says Beatrice K. Otto, historian and author of Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World (via History Today).

Over in Europe, Otto says (via the University of Chicago Press) that the earliest form of the jester was the actors of ancient Rome. They — and their commentaries on contemporary events — were the inspiration for later jesters. And it was a dangerous profession. The Smithsonian says there's plenty of stories of these Roman jesters not only poking fun at the upper echelons of society, but being killed for it. It's a classic case of knowing your audience and reading the room.

Strangely, there was a major stipulation put on these early actor-jesters. At the same time they were taking aim at some seriously powerful political figures, they couldn't be citizens of the Roman empire themselves.

Jesters could be recruited from anywhere

So, how exactly did one become a court jester? Beatrice K. Otto, historian and author of Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World, says (via the University of Chicago Press) that if the right person saw you being funny, you might have a foot in the door.

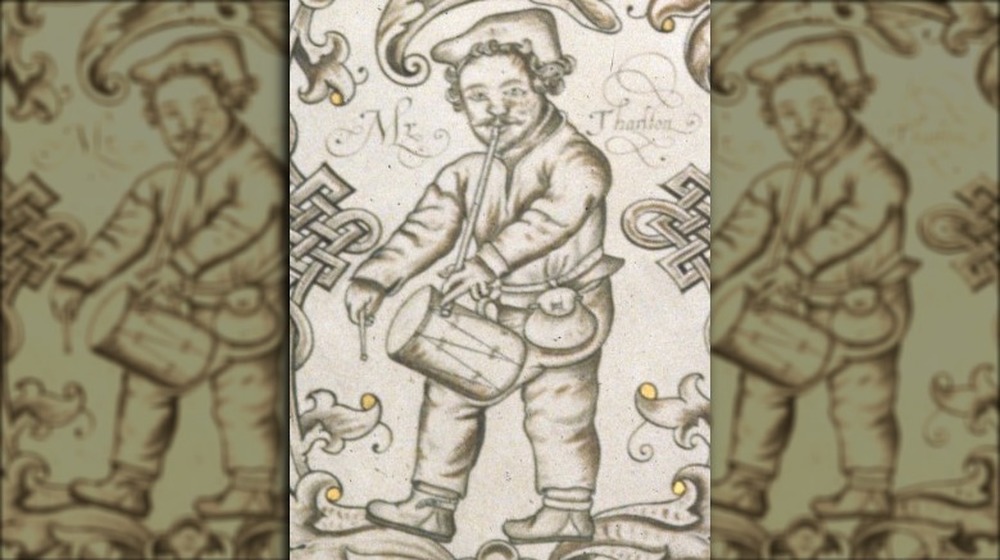

Jesters often started out doing something completely different. In Russia, jesters were frequently plucked from among the elderly serfs, because they liked their humor of the dry and bitter-old-person variety. Elizabeth I's favorite jester, Richard Tarlton (pictured), was discovered in a field tending to his father's pigs. One of the jesters that served King Mongkut of Siam was discovered on a hunting trip. And sometimes, they were the sort of people who wanted to be jesters for the safety it provided.

Unsurprisingly, the sort of person who made a great court jester is also the sort who had a lot of people wanting to give them a sound thrashing, and getting some royal favor was one way to avoid beatings, law enforcement, or creditors. The Scottish Archie Armstrong was a known sheep thief, and he made his way to the court of first James I then King Charles I as a jester. Unfortunately for him, some of his jokes didn't quite land and he was kicked out of court in 1638 (via ESCJ).

Jesters held an incredibly important role in Chinese courts

While different cultures might have different ideas of what's funny, Beatrice K. Otto, historian and author of Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World says (via History Cooperative) that the need for humor is pretty universal.

Otto says that there's striking similarities between the jesters of European courts and those that held positions in China. Ancient Chinese texts mention the presence of jesters throughout Chinese history, and one of the most famous was Dongfang Shuo, who regaled the Han Emperor Wu Di with his antics during his reign from 140 to 87 BC.

Jesters in these ancient courts weren't just there to tell jokes, and Otto says they were just as much diplomats as comedians. They needed to be intelligent and observant enough to see mistakes that were about to happen, and make fun of the situation in a way that made their ruler stop, take a step back, and fix little problems before they turned into big ones. They were also employed as ambassadors and even translators. Having a jester between two rulers from different cultures speaking different languages made it possible to deflect unintentional insults from things like mistranslations or social faux pas, and many were extremely good at diffusing even the tensest of situations.

There were different types of medieval fools

According to the BBC's HistoryExtra, court jesters weren't a one-size-fits-all sort of deal. There were a few different types of jesters by the Middle Ages, and what they did depended on which they were. First, there was the "professional fool," and those were the ones that acted as advisors. They're the ones that relied on wit and snide comments — coupled with some serious charm — to essentially be their ruler's right hand, confidant, and keeper. They weren't the ones wearing the stereotypical motley, but often dressed in the clothes of a noble.

Then, there were the "innocent fools," who weren't paid in money, but were fed, clothed, and given a place to sleep. And for many, it was a step up: they were men and women who, today, would be diagnosed with mental illnesses. Physical deformities might also bring someone to the attention of a monarch looking for an "innocent fool." Jeffrey Hudson, for example, was a dwarf who was gifted to Queen Henrietta Maria (both pictured) and became her favorite "pet," until he proved himself in battle and was given the title of captain of the horse.

Then, there were also Fool Societies, troupes of wandering entertainers that were hired to perform at court of public events. These were the classically-clad motley fools, and they were the ones doing things like juggling, dancing, and acrobatics.

What was — and wasn't — fair game for the court jester

Being successful as a court jester meant a person wasn't just funny but knew where to draw the line. Notre Dame Magazine says there's numerous stories of jesters who got up close and personal with that line, then managed to talk themselves out of an execution order. Legend says that one jester in ancient China managed to keep his head by pointing out that if the emperor were to take it for himself, it would no longer do him any good.

The line could get a little blurry. Take religion: while the Church, religious doctrine, and beliefs were off-limits, ridiculing wayward church officials who didn't live up to the demands of their offices was practically a job requirement. In some cases, rulers would tell their jesters what they wanted them to make fun of. Peter the Great, for example, wanted to modernize Russia, and he did it in part by instructing all his jesters to ridicule the old ways and beliefs.

And, in most cases, the king or queen was fair game, too — and jesters could say what everyone else was afraid to say. Thomas Killigrew (pictured), the jester of Charles II, made it a point to shine a spotlight on the king's bad habits. When Charles asked him about those faults, he responded, "No, faith, I don't care to trouble myself with that which all the town talks of."

The court jester could have held additional jobs

Being a jester wasn't a full-time job, and if there's anything that a medieval court didn't like, it was useless mouths to feed. According to the BBC's HistoryExtra, jesters only performed for the court on irregular occasions. They would have been called to center stage during large banquets and celebrations, and weren't asked to tell jokes on a daily basis.

That meant jesters needed to make themselves useful in other ways, so many held jobs in addition to being the court's entertainment. Common occupations were things like the keeper of the hounds, or negotiating deals at local markets on behalf of the court.

One of Europe's most famous jesters had what was arguably one of the best second jobs in the Middle Ages. Perkeo (pictured) was a jester in the 18th century court of Prince-Elector Carl Philipp von der Pfalz, and he was so popular that there's still statues of him all over Heidelberg. He also acted as cup-bearer, steward, and overseer of the royal wine stores, which included the Great Barrel. The barrel was so big that there was a dance floor on top, and it held 220,000 liters (or nearly 60,000 gallons) of wine.

Court jesters were expected to act as battlefield messengers

The court jester's only place wasn't within the safety of the court and the very high walls of the castle, and when things got ugly outside, they were often taken to the front lines.

According to the BBC's HistoryExtra, anyone wanting to become a court jester during times of war and conflict might want to think twice about that. They often accompanied their king to battle, and more than that, they were employed as messengers. When it came time to send a message to the opposing army's leaders, it was often the jester who saddled up and rode out.

Predictably, that didn't always go well. While jesters would often carry messages back to their king or queen in return, sometimes the message was to return the jester in multiple pieces. If the opposing army really didn't like the demands or terms set out in the message, the jester-turned-messenger was unlikely to see the next sunrise. There are records of jesters (or their heads) being returned to their king via catapult, and that's a job hazard that's just not worth the pay.

Court jesters also entertained the troops

Battles in the Middle Ages may have been fought on horseback with swords, shields, and spears, but they were already well aware of the power of some good ol' psychological warfare. Enter, the jester.

Jesters that accompanied their king or queen out to battle were often tasked with not just entertaining the royal court, but the troops as well. On their own side, the BBC's HistoryExtra says they often circulated before battles, telling stories, making people laugh, and generally keeping morale as high as it could be among men who knew they were probably riding to their deaths at dawn.

They were also sent out into the sort of no man's land between the armies, and told to mock, ridicule, and provoke the other side... preferably while staying out of range of their arrows. The idea wasn't just to dishearten the other side — while amusing their own faction — but it was also an attempt to get opposing soldiers to break rank and create a weak point in their defense. The court jester literally had to provoke hot-headed maniacs to try to kill him, and presumably, the ability to run fast was a highly desirable skill in the jester's arsenal.

They were expected to be ugly... or were made that way

The next time anyone goes on about the good old days, remind them of the fact that in the Middle Ages, deformities were considered pretty hilarious.

The Boston Lyric Opera says that dwarves in particular had a good shot at being hired as a court jester, and that's just part of the story. They also say that dwarf jesters were so popular, attempts were made to stunt the growth of children so they would be able to be sold as fools. Some 17th century documents even gave directions for procedures thought to halt a child's growth, which could involve things like applying a concoction of grease made from dormice, bats, and moles to a baby's spine.

The Opera National de Paris says that it was widely believed that those with deformities like a hunchback were generally smarter and more quick-witted than others, and according to Harvard Medical School psychiatrist Steven Schlozman (via Owlcation), jesters who had their jokes fall flat might find themselves being disfigured even further. Many had their mouths mutilated into a permanent smile by angry monarchs who ordered the severing of the muscles that allowed them to frown.

Favorite jesters had unprecedented access to the monarch

The role and place of a jester at court changed a lot over the years, and according to the BBC's HistoryExtra, it wasn't until the War of the Roses (which ended in 1485) that the jester went from court employee and performer to close confidant of the king.

The very first fool recorded as part of Henry VIII's entourage was a man named Sexton (or Patch). He was replaced after he made some questionable comments about Anne Boleyn and her daughter Elizabeth, but his replacement — William Somers — was much more successful. He wasn't just a jester, he was a close companion that came and went from the king's inner chambers as he pleased. It was a privilege that no other advisor enjoyed, and he ended up staying at court through the rule of Edward VI and Mary I. To show just how important he was, he was included in Henry VIII's 1545 portrait of his perfect family (pictured)(via Historic England).

Elizabeth I's favorite fool, Richard Tarleton, was credited with having "cured her melancholy better than all her physicians," and James I's Archibald Armstrong was such a valued counselor that he was one of a few advisors who went to Spain with Prince Charles on a secret mission to secure a bride. After the rise of Charles I, though, court jesters largely went back to their former status as performers — without the privilege.

Women could be jesters, too

Although the Boston Lyric Opera says that the majority of jesters (at least, those remembered by history) were men, there were a number of wildly famous female jesters as well. Show World says the tradition of female jesters goes all the way back to the ancient world, when troupes of ancient mimes included female performers. Fast forward to medieval Europe, and history recalls tales of the so-called Gleemen who traveled the English countryside, often in the company of a female acrobat and jester called the Glee-maiden.

There were famous female court jesters, too. Mathurine served at the French court in the 17th century, and was known for dressing like an Amazon warrior (complete with wooden sword). She was so popular that the era's satirists named themselves after her, and a form of burlesque comedy based on her act also took her name. Queen Henrietta Maria, Edward I and II, and Catherine de Medici also employed female fools, and a jester named Jane the Fool served Anne Boleyn, Princess Mary, and Katherine Parr (via Historic England). Pictured is Elisabet, the fool of Anne of Hungary.

According to Cornwall Live, female jesters had more than a few tricks up their sleeves. In addition to the jokes and witty comments their male counterparts specialized in, they also tended to be trained in things like dance, contortionism, and acrobatics.

Court jesters could have been recruited into shady dealings

Being a court jester wasn't always just fun and games, and there's at least one story that suggests jesters could be recruited into some questionable activities.

Muncaster Castle (pictured) has been in the Pennington family for more than 800 years, and it was in the middle of the 16th century that Sir Alan Pennington hired Tom Skelton as both a jester and steward to the head of the family, then 14-year-old William Pennington. (We think. As Mental Floss says, there's few official records of Skelton. As he was a servant, most of his story has been preserved simply by word of mouth.)

The story says that he got roped into a tale of unrequited love when Sir Alan's daughter Helwise fell in love with a lowly carpenter, and spurned the interests of a knight named Sir Ferdinand. Ferdinand was out for revenge, and convinced Skelton to get the carpenter drunk, then chop off his head — which he did. The attempt to win Helwise for Ferdinand failed, and she spent the rest of her days in a nunnery. Perhaps also unsurprisingly, the BBC says Skelton was the Pennington family's last fool until a 21st century competition resurrected the position.

They could have a decent retirement

If a court jester survived the pressures of the court and the dangers of the battlefield, it was entirely possible the reward might be worth it. According to the BBC's HistoryExtra, it wasn't uncommon for jesters to be given some impressive perks for their years of service.

Henry II, for example, gave a court jester named Roland le Petour 30 acres of land to retire on. The only condition was that on every Christmas Day, he returned to regale the court with a performance in which he was instructed to "leap, whistle, and fart." (Humor wasn't that different, after all.)

One of the last court jesters that history remembers got an impressive retirement, too. Samuel Johnson was widely known among English elite as Maggoty Johnson thanks to a pockmarked face. He had the last laugh, though: Gawsworth Life says that when he retired, he was given Gawsworth New Hall as a gift. He died when he was 82, and was buried in the church's graveyard in spite of the fact that he was very vocal about not wanting to be interred there. (There was a woman buried there that he'd hated.) His earthly remains were eventually reburied in a tomb located in Maggoty Wood (there's a plaque there now), and his violin is still on display in Gawsworth Old Hall.