What It Was Really Like Being A Mountain Man In The 1800s

Tough. Resilient. Determined. Adventurous. These are just some of the words used to describe the mountain men (also commonly referred to as fur trappers) who rambled all over the Rocky Mountains — but also eastern parts of early America — as far back as the 1500's. By the early 1800's, says Legends of America, Joseph Dickson became one of the "first known mountain men" when he traveled alongside explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on the Missouri River. Dickson and others like him literally made the wilderness their home, embracing the seasons as their time clock and living off the land as they made their way through the mountains, says X Roads. The life could be harsh, even brutal, but somehow many of these men prevailed.

If the idea of a fellow hunkered down dressed in animal skins while living out of a makeshift shelter and cooking meat over a fire sounds romantic, well, in a way it was. Homestead calls mountain men "America's original survivalists" who were fiercely independent but also lived a fairly solitary life. Movies like 1972's Jeremiah Johnson have created the ideal mountain man in our minds, but what was it really like to live through harrowing snowstorms, high desert heat and the knowledge that one small mistake could cost one's life? Read on to find what it was really like to live as a mountain man.

The calling to live as a mountain man

In 1980's The Mountain Men, Bill Tyler (Charlton Heston) says to Henry Frapp (Brian Keith), "I heard you got in on the money end of this miserable business." Frappe replies, "Yep. Packed in supplies, watered down the whiskey, jacked up the prices...and went to tradin' for beaver." Tyler asks, "How'd ya do?" Frapp answers, "I lost my ass!" Even those trappers working for one of several fur companies found making money was tough, even grueling work. But the way Homestead explains it, mountain men experienced a freedom like no other, "living out their passion in the heart of Mother Nature's bounty." The woods were their workplace, and there were no rules to follow except their own. Adventure, but also peril, lay around every corner.

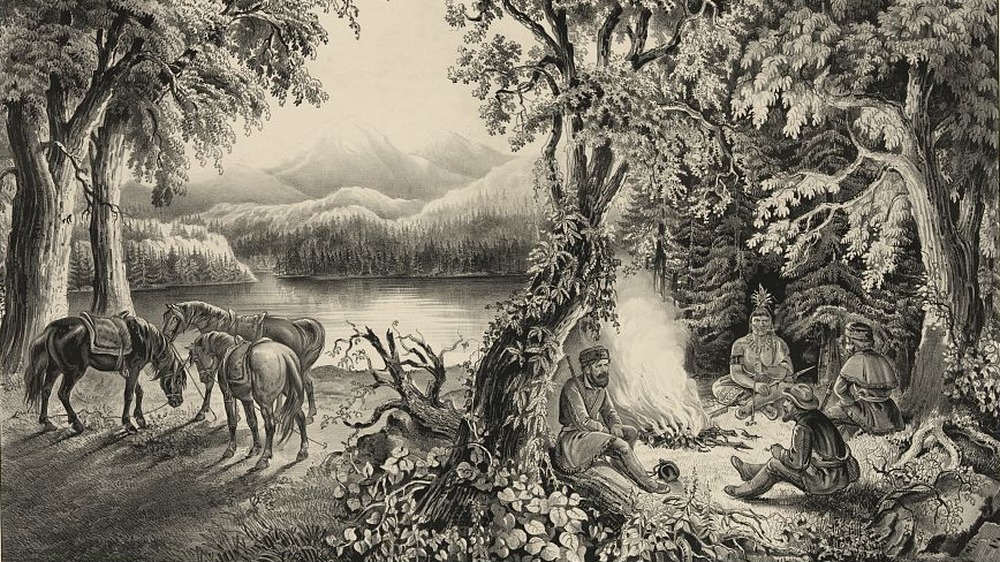

During the 1800's animal pelts, especially beaver, were highly sought after in the American West and Europe. Because of this, explains the National Cowboy Museum, early mountain men had the freedom of hunting game wherever and whenever they wanted, trading with both Anglos and Native Americans for money or the things they needed to survive. X Roads explains that mountain men could find companionship at the annual rendezvous at which other trappers, traders, and Natives gathered to celebrate, feast, trade, and perhaps even find a wife. The rendezvous gave the men a needed break from their loneliness out on the trails.

Why the west needed mountain men

The National Cowboy Museum explains that mountain men actually played an integral part in the development of the American West, namely contributing to Westward Expansion. In Europe, beaver felt hats were all the rage as early as the 1600's, as well as mink, fox, marten, and other furs. Their pelts and skins were sold in America but also Europe, guaranteeing amicable relations between mountain men and businessmen. They became experts at trading with and learning about Native Americans and their way of life. In turn, says Montana Trappers, the Native culture developed as indigenous people received not just furs but also manufactured tools and weapons, as well as tobacco, liquor, glass beads, and clothing.

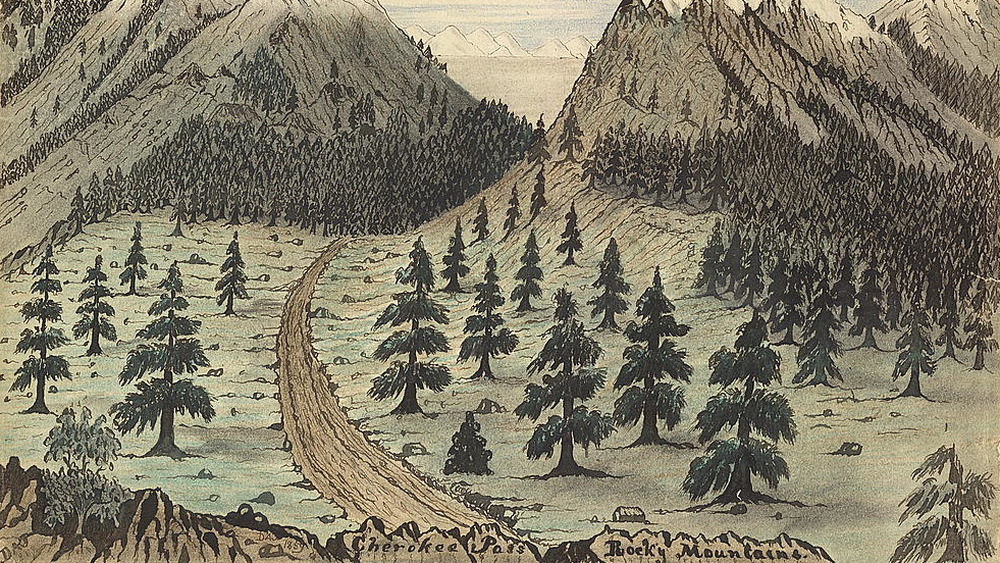

There was another reason mountain men were important to the development of the west: the trails they discovered. History on the Net explains that it was these men who forged their way over mountain passes and knew which trails were safe and which ones posed danger. According to Digital Atlas, trappers also learned the animal trails, mapped important streams and rivers, and noted where feed for livestock and horses was ample. They also learned which Native tribes were most dangerous, as well as which ones were friendly and open to trade. In later years, the men's trails were used by immigrants coming West.

At home in the wilderness

A successful mountain man carried plenty of provisions so he could live just about anywhere on his travels. The best equipped of these, says Homestead, used at least one but as many as two to three horses to carry such essentials as an axe, hatchet, skinning knife, traps, cookware, flint to start fires, blankets, coffee, flour, and a bota bag-type water container. Since few mountain men were able to purchase bullets, they also carried bullet molds, gunpowder, and lead. Those with money and other valuables kept them in a poke.

The lonely winter could be a man's worst enemy. It was important to stock up extra food for the winter months, says X Roads. Failure to do so could result in subsisting on roots or even mule or horse meat. Some mountain men wisely chose to winter at a small variety of forts across the west. The Fur Trapper cites Fort Henry in North Dakota as being "the first American post west of the Continental Divide." In summer, the nearby Snake River provided beaver and fish, but winters could be brutal. Author Janet LeCompte wrote that while some men spent their winters at Bent's Fort (pictured) along the Santa Fe Trail, negotiations with Kiowa and Comanche tribes could prove difficult. Frontiersman "Uncle Dick" Wootton remembered one winter where the men were confined to the inside of the fort due to unfriendly Natives.

A typical day in the life of a mountain man

Following winter, mountain men embraced the spring thaw and began the trapping season proper. A typical day, says Grand County History Stories, began with a breakfast made with whatever was on hand. Some men made "boudins," a sausage made from the intestines of their kill. Alternatively, pemmican was a dried combination of meat and fruit. Wild potatoes and grass, hard crackers, and coffee or tea (made from shavings of Chinese tea blocks) completed the meal. The rest of the day, according to the Center of the West, was spent maintaining camp, cleaning or repairing the guns, mending or making clothing, harvesting kills, and drying out pelts.

Come evening the men prepared their campfire, checked their traps again, and prepared their dinner. If they caught a beaver, they might make soup out of the tail. Extra meat was made into jerky, says Civil War Recipes, by adding salt and spices to raw game and hanging it over a small fire to dry. No spices? Bison dung on the fire was said to add a "peppery flavor" to the meat. Arizona historian Marshall Trimble writes that because food could be scarce, many trappers were known to eat "four or five pounds of meat at a sitting." If there was no meat, a man might resort to eating ants or crickets; some even had to soak their moccasins in water and eat them if no other food was available.

The grizzly work of hunting and trapping

Mountain men began the spring season of fur trapping at points where the ice had melted in the streams, explains Fur Traders & Rendezvous. Then they slowly followed the thaw through summer, working their way to higher elevations. In the Rocky Mountains, that could mean trekking as high as 14,000 feet in elevation. Osbourne Russell, says X Roads, guessed that the average trapper carried six traps. These, explains Homestead, were made from steel weighing 3 1/2 pounds and were attached to a tree root or a rod hammered into the ground. Essential for catching beaver was a special bait made by pulverizing nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, and the secretion from "castor glands" found in beaver. Today the secretion is still used in certain medicines and perfumes.

Once the traps were set, according to The Fur Trapper, they were checked once in the morning and again at night. The Michigan Association of Fish & Wildlife explains the dead game was then dusted or washed free of dirt and grass if needed, dried as much as possible, and skinned onsite. Next came fleshing the fur—the process of removing any extra meat that could spoil the pelt. The pelt was then attached to a hoop and left to dry, usually for several days. The average pelt weighed about one and a half pounds, and a standard "beaver pack" weighed some ninety pounds by the time the trapper took his haul in for trade.

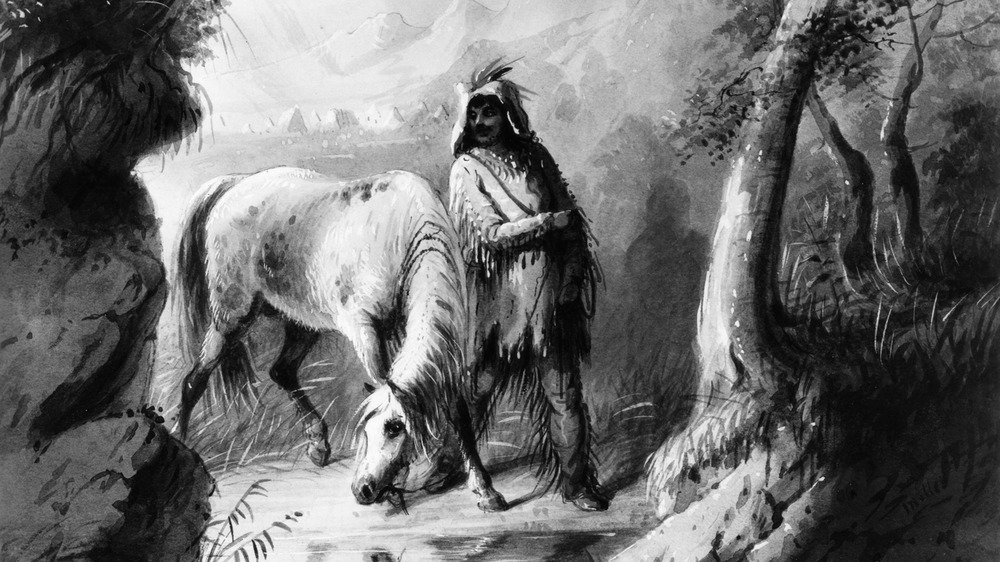

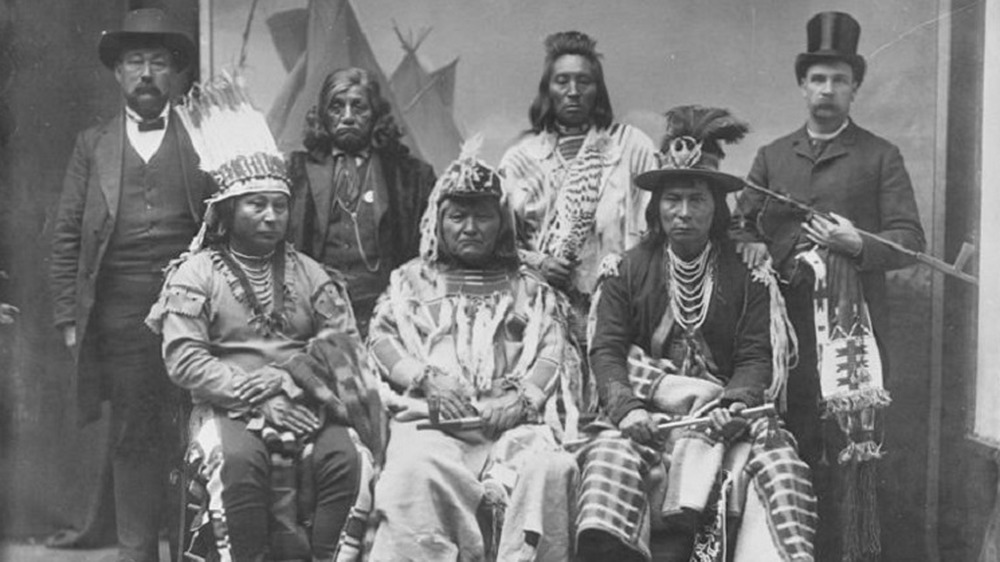

Mountain men established connections with Native Americans

Early on, mountain men in the wilderness encountered unfriendly tribes who resented their presence. Homestead cites some of the earliest attacks being made by Blackfoot and Comanche tribes. In time, however, both sides found that they shared a common bond: the love of trading. Especially at the annual rendezvous of the early 1800's, says Hobble Creek, mountain men could actually buy or trade furs from the Natives, offering them goods in exchange. The men also appreciated the Native ways and customs, because they could learn additional needed survival skills. History on the Net confirms that some mountain men were quite welcome and at home living among the tribes. Doing so and learning their language only increased friendly communications between the two.

Before long, fur companies saw the benefits of good relationships between mountain men and Native Americans. Some, says The Fur Trapper, hired trappers specifically to work with the Natives. The trouble was that certain tribes—namely the Arikara, Blackfeet, and Sioux—strongly objected to Americans trading with their enemies, especially when it came to firearms. The Arikara in particular served as a middle-ground tribe on the plains. Because of this, maintains U.S. History, relationships between mountain men and Natives remained tentative at best: some Anglos made their home among the tribes, while others gained fame for the number of Indians they killed.

Mountain men and the annual rendezvous

In the early years of the fur trade, says Rocky Mountain National Rendezvous, trappers and mountain men spent part of the year transporting their furs all the way back to St. Louis, Missouri to sell their harvest and buy needed supplies for the next trapping season. Beginning in 1825, however the men found it easier, and often more profitable, to stage an annual gathering in the West. The majority of these rendezvous occurred in Wyoming, says Wyoming History, with the first event taking place at Henry's Fort (aka Fort Henry). Traders from Missouri, says Legends of America, could haul supplies over to the rendezvous instead and trade with everyone at once.

History Colorado confirms that furs and pelts quickly expanded to include deer, muskrat, otter, raccoon, and wolf hides, as well as bison. But beaver pelts, says White Oak Historical Society, remained the most popular. Equally important was the social aspect of the annual rendezvous, where the men could blow off some steam after spending so much time alone, says X Roads. Some of those in attendance later wrote that participants drank themselves silly, swapped stories, sang and danced, gambled, raced horses, practiced target shooting and more while bargaining for needed supplies. Naturally they also traded with Native Americans, says Gentle Dove History, sometimes taking Native women as wives.

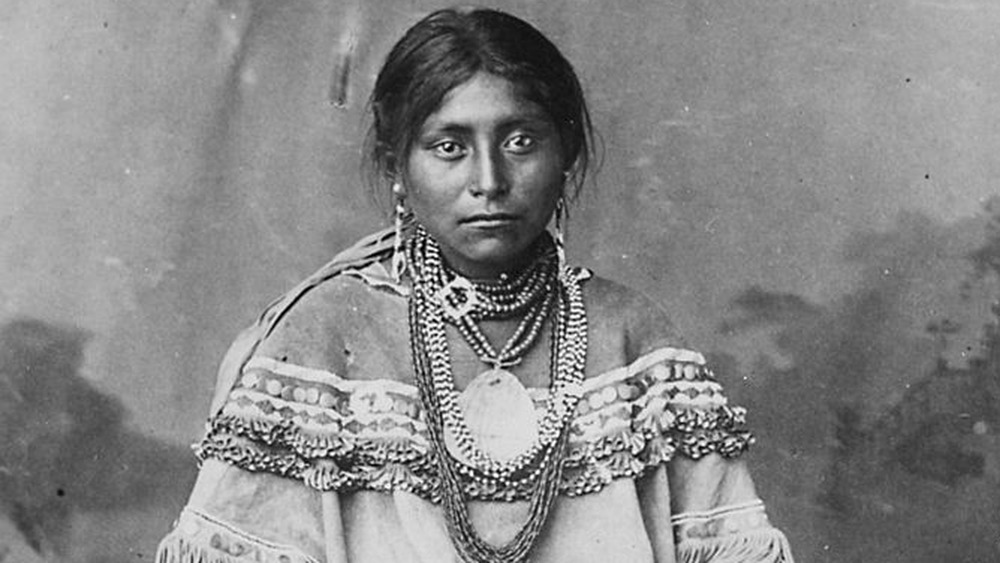

Mountain men often married Native Americans

There were very good reasons for a mountain man to take a Native wife. Gentle Dove History explains that the women knew all about living in the wilderness, from breaking horses to camp duties to using weapons. An Anglo husband inherited his Native wife's relatives, enabling him to establish further trade with his in-laws. Displays at the San Bernardino County Museum in California confirm that there were very few Anglo women during the fur trade era. Referred to as "Tender Exotics," in the early west, white women were usually married to fur company managers. Of those mountain men who took a wife, nearly half of them were with "Indian or mixed-blood women." These unions helped both Anglos and Natives learn each other's language and customs.

To the Natives, says Bear Lake Rendezvous, the marriage of their women to Anglos was ideal. They felt that marriage "created a social bond which served to consolidate economic relationships with the traders." Native Americans were already long accustomed to lending or trading their wives and daughters to Anglos for sex in exchange for goods, an ideal situation to all parties involved. But marriage secured an ongoing relationship whereby all parties (including the women) benefited further from the union. Some tribes, such as the Cree, were in the habit of reserving their daughters specifically for marriage to a trader.

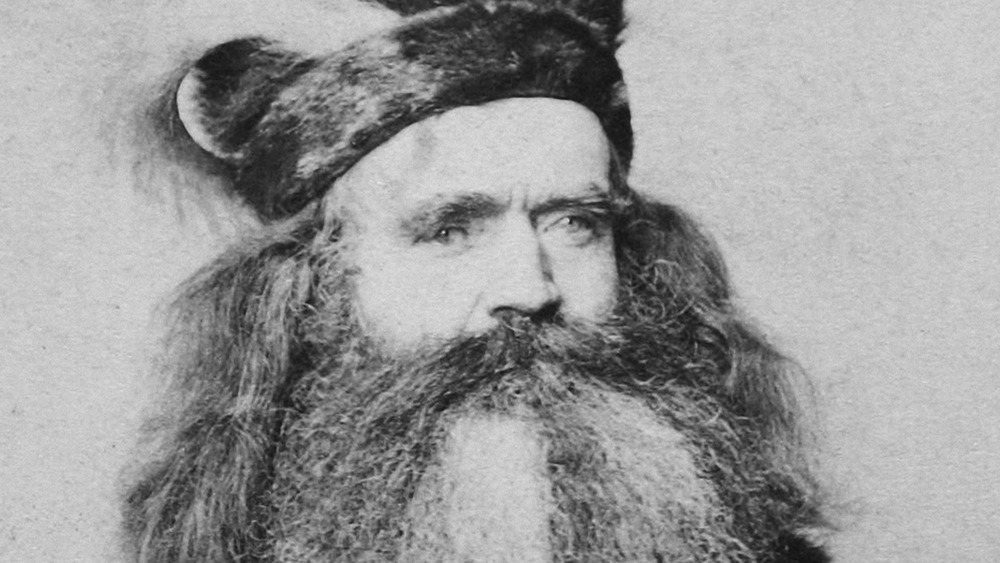

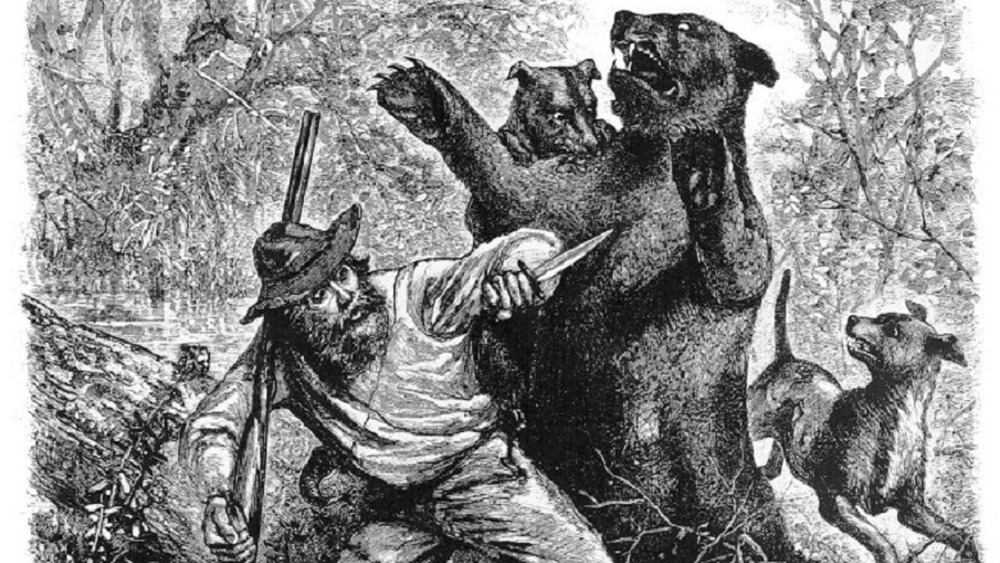

Kit Carson, Hugh Glass, and other famous mountain men

Not surprisingly, some of the most famous mountain men in America had Native American wives. Smithsonian verifies that Kit Carson's first two wives, for instance, were an Arapaho woman named Waa-Nibe and a Cheyenne woman named Making Out Road. History documents Carson as having learned several Native languages. He also served as a guide, made numerous excursions across the Rocky Mountains, and served in the military. Even more colorful to historians today was Hugh Glass (pictured), whose amazing survival of a wicked bear attack was portrayed by actor Leonard DiCaprio in the 2015 movie The Revenant.

Lesser-known but equally important mountain men include "Rocky Mountain Jim" Nugent, a colorful mountain guide in Estes Park, Colorado who also survived a bear attack, but was eventually shot by his rival, Griffith Evans. Notable too is one of the very few mountain women, Marie Dorion. Outdoor Life says Dorion survived the death of her fur trader husband, spent a winter traveling 250 miles across the Blue Mountains with her two young sons, and eventually settled along the Columbia River in Oregon where she remarried and had more children. Her ancestors actually settled the Willamette Valley.

John Colter was the first mountain man in the west

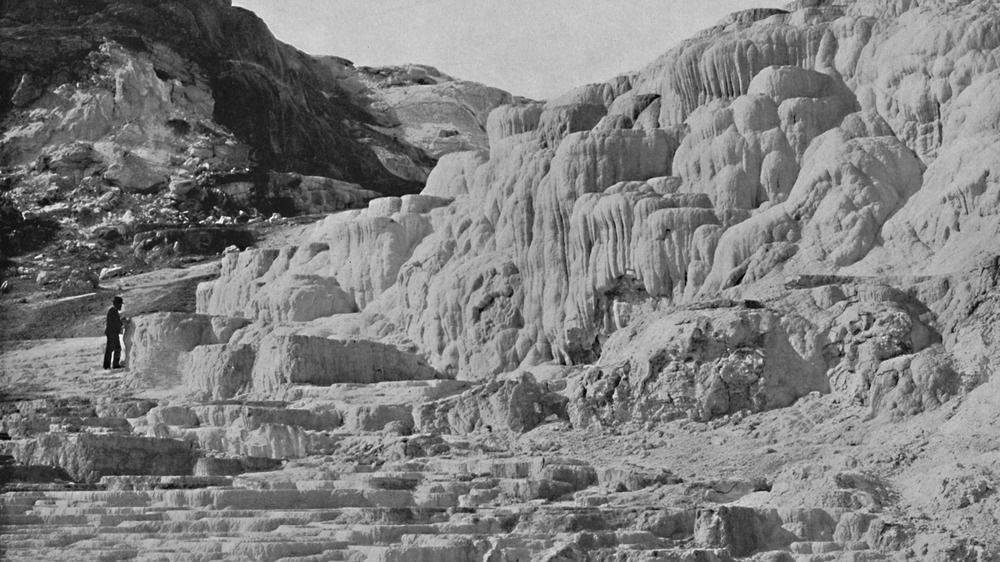

Of all of the mountain men who scrambled around the wilderness in the 1800's, the honor of being the very first one goes to John Colter. Legends of America writes that the Virginia-born trapper enlisted with Lewis and Clark's expedition in 1803 for just $5.00 per month. He quickly became known for his hunting and scouting skills. At the end of the expedition, the Virginia Argus would later report that Colter was awarded 1,600 acres for his work, but wasn't quite ready to settle down. Instead, he joined up with trappers Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson and headed further west.

Eventually Colter worked as a guide for the Missouri Fur Company. He is guessed to have rode alone over an estimated 500 miles in search of Native American camps as he spread the news of available trade. Britannica states that in 1807 Colter was the first Anglo man to see today's Yellowstone National Park. But his descriptions of the geothermic wonders were so vivid that few believed him. According to Grand Teton National Park, the story that Colter's friends called his "imaginary place Colter's Hell" is false; that term was actually applied to an area along the Shoshone River near Cody, Wyoming, not Yellowstone. Colter eventually married, had a son, and bought a farm in Missouri says X Roads, dying in 1813.

The end of the fur trade

The conclusion of the fur trade era is attributed to three major events: a serious decline in fur-bearing animal populations, poisonous chemicals which made making beaver felt hats unhealthy, and England's Prince Albert (pictured with his family) switching to wearing silk hats. Bear Lake Rendezvous also submits that "killing an animal for fur became less politically correct." By 1840, says Northwest Power and Conservation Council, the fur trade was officially declining. Between 1841 and 1845 the Bay Company, for example, took in roughly half of the number of furs the firm had normally purchased in years past.

Bay Company eventually turned to other industries such as lumber and agriculture. Other companies such as The American Fur Company, says Legends of America, went broke. Worse off were the Native Americans, who "were plunged into long-term poverty and consequently lost much of the political influence they once had." When traveler Rufus Sage visited Colorado's Middle Park in 1842, says Grand County History, he observed there was "almost no hunting activity there." Montana Trappers verifies that almost all fur trading activities had ceased by 1870. "The fur trade is dead in the Rocky Mountains," mountain man Robert Newell told his colleague, Jim Bridger, "and it is no place for us now, if ever it was."

New careers for old mountain men

With the end of the fur trade, mountain men were caught in a quandary, according to X Roads. What would they do for a living? The last annual rendezvous took place in 1840, says Bear Lake Rendezvous, but Manifest Destiny was just around the corner as two international treaties in 1846 and early 1848 gave the United States official ownership of the Pacific coast. Who better to lead emigrants west than the very men who established the trails leading there? Many mountain men, according to History on the Net, found new jobs serving as guides not just to folks headed west but also the military. After all, the men knew the best routes, where the rivers were, and the locations of unfriendly Natives.

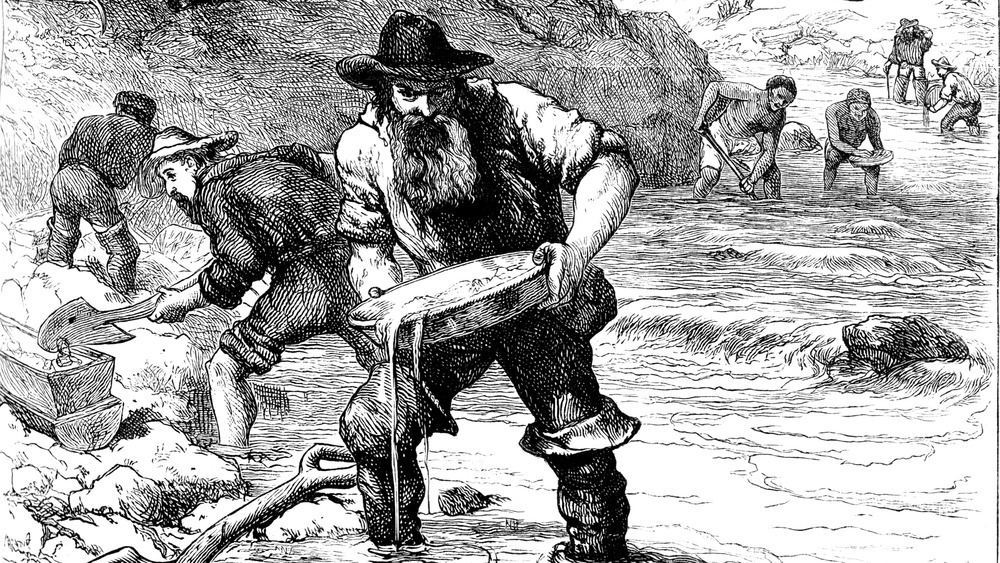

Another saving grace for mountain men seeking new jobs was the California Gold Rush of 1848. History credits the discovery of gold in the Sacramento Valley as being "arguably one of the most significant events to shape American history during the first half of the 19th century." Many a mountain man was soon trying his luck panning for gold or working in one of the larger mines. The quest for gold soon spread all over the west, according to the Pagosa Springs Journal in Colorado, with mountain men turning to prospecting to make their way. Their memory has not quite faded, however. Today, numerous Mountain Man Rendezvous across the west keep the history of our illustrious mountain men alive.