The Tragic Story Of England's Teen Queen, Lady Jane Grey

Plenty of words have been written about the drama of Tudor England. There's the tumultuous life of Henry VIII, who broke away from the Catholic faith while dumping his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, for Anne Boleyn. Ultimately, Henry would cycle through six wives and produce three children: Mary, Elizabeth, and his longed-for male heir, Edward. On his deathbed, Henry may have sighed in relief, believing that, for all the trouble he'd caused, his bloodline would continue through his son. Yet, years after his son became Edward VI, the boy king died and left the throne of England wide open. That's where Jane Grey came in.

As a cousin to Edward VI, there was no denying that Jane had royal blood. What's more, she was a devout Protestant. That put her in a truly awkward position, as some Protestants wanted her on the throne. Meanwhile, others thought that the Catholic Mary should take over her younger brother's job.

Ultimately, Jane Grey was pushed onto the throne and, within the space of only nine days, knocked off it again. A few months later, Queen Mary ordered her execution. Though much of her story concentrates on those fateful few weeks just after Edward's death, there's more to Jane than her time as a maybe-queen of England.

Lady Jane Grey was highly educated for a Tudor woman

Life in Tudor England held a variety of different paths for women, though nearly all of them were limited by rampant sexism and poor education. As the BBC's History Extra reports, girls of many different social classes were often given subpar tutoring. Educator Richard Mulcaster, writing in the 1580s, blithely stated that "naturally the male is more worthy" of proper education, anyway. Why would parents waste the time and money to produce learned daughters when their future roles were supposed to revolve around motherhood and dependence on their husbands or other male relatives? At best, some girls might get an apprenticeship that could help them be semi-independent.

Not everyone took this tack. The Sisters Who Would Be Queen says that there was briefly a trend amongst the upper class for giving daughters a good education. Frances, Jane's mother, appears to have been set on making sure her daughter followed the fashion. Jane seems to have really taken to her education. Historic Royal Palaces says that she was so into classical works that she preferred reading to more popular pursuits like hunting. "I wist all their sport in the park is but a shadow to that pleasure that I find in Plato," she said. "Alas, good folk, they never felt what true pleasure meant."

Home life was difficult for Lady Jane Grey

In a letter quoted by History Extra, Jane praised God for sending her "so sharp and severe parents, and so gentle a schoolmaster." Those brief words seem to underlie a complicated situation that included a difficult family life for young Jane. Her ambitious parents, Frances and Henry, wanted Jane to be ready for whatever political machinations they produced for her. To that end, they apparently became demanding "tiger parents" who wouldn't tolerate the slightest slip-up.

"For when I am in presence either of father or mother," Jane wrote, "where I speak, keep silence, sit, stand, or go, eat, drink, be merry or sad [...] I must do it in such weight, measure, and number, even so perfectly as God made the world, or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened [...] that I think myself in hell." Her tutor, John Aylmer, however, was so kind to Jane that he soon became a beloved fixture in her life and a relief from her mother and father.

However, some historians think Jane may have embellished the situation to gain sympathy. The Economist notes that, after her death in 1553, Jane quickly became mythologized as a martyred innocent. Furthermore, Jane's above-quoted letter was only published in 1570, in a book by scholar Roger Ascham.

A sickly king and religious upheaval set the stage for Queen Jane

As Jane grew up, England was ruled by Edward VI, the young son of Henry VIII who, according to Tudor Times, had inherited the crown when he was only 9-years-old. History Extra notes that there was even a brief but ultimately unsuccessful plot to marry Jane to Edward. That deal was brokered by Thomas Seymour, husband to Katherine Parr, who was herself Henry VIII's widowed final wife. There were few strangers in the Tudor court, it seems.

Then, the young king grew terribly ill. Britannica reports that Edward had apparently contracted tuberculosis by January 1553. By the spring, it was obvious that he was facing death. It's not clear if his plans for the succession, which ousted his sisters Mary and Elizabeth in favor of Jane Grey, were his idea or those of the Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley. Northumberland was Lord Protector and one of Edward's closest advisers. He was also as much a loyal Protestant as the king he advised and the father-in-law of none other than Jane Grey, who had married his son, Guildford, in 1553.

For the first time, England's throne had no male contenders

As it became clear that the unmarried Edward VI was deathly ill, he drew up a "Devise for the Succession." According to the Library of Congress, in this document, Edward tried to make it so the crown would only go to his female relatives' male heirs. However, there were serious issues with this plan. First, his two elder sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, had both been declared illegitimate at one point by their father, Henry.

A 1543 statute had opened up a way for Mary and then Elizabeth to get the throne anyway, but that didn't sit well with Edward. He was a faithful Protestant and Mary was a devoted Catholic. A Queen Mary could completely upend the Protestant Christianity that had just begun to take root in England.

Edward's new plan, created under the influence of the Duke of Northumberland, named the devoutly Protestant Jane and her male heirs as the new successors. However, this document landed in a legal gray area, leaving just enough room for its validity to be questioned mere weeks after the young king died.

The Duke of Northumberland was the mastermind behind Jane's ascension

All of Jane's education and social training might have granted her only an obscure place in history if it weren't for her family's association with the Duke of Northumberland. Their meeting may have come about after, as the BBC reports, Jane's father Henry was made Duke of Suffolk in October 1551. By then, it was pretty clear that John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, was the real power behind the throne.

Northumberland was clearly a Protestant powerhouse and political heavyweight, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia. He proved himself a decisive military leader in August 1549, when he led an army against homegrown rebels in Norfolk. Riding on that military victory, he became the Lord Protector only two months later, effectively making himself regent to young king Edward VI. Once he took out most of his rivals, Northumberland was one of the most powerful men in the land.

Upon realizing that Edward was dying of tuberculosis without ever marrying and producing legitimate heirs, Northumberland would have none of a Catholic Mary on the throne. He very likely pushed Edward to name Jane, the king's cousin, as the true heir. Jane had also married Northumberland's son, Guildford, in 1553. Perhaps the duke had visions of his own son as king, once again placing him right behind the royal throne as the true voice of power in the realm.

Things moved quickly for Lady Jane Grey after Edward's death

After a months-long struggle with tuberculosis, the 15-year-old Edward died on July 6, 1553. The Duke of Northumberland's plan sprang into action nearly as soon as the young king took his last breath. According to Historic Royal Palaces, Jane was brought to Northumberland's London residence, Syon House three days later, on July 9. There, she was told she was queen. Apparently, this was the first time that Jane herself learned of her place in her father-in-law's plan to maintain his hold of power.

Lady Jane Grey reports that the whole thing came as a shock to the 16-year-old girl. At Syon House, a number of men appeared and knelt before the confused and increasingly distressed Jane. Eventually, Northumberland explained that the king had died. More importantly, before his passing, Edward had determined that Jane was to be his heir, though he seemingly never bothered to let Jane or her family know.

Upon hearing this news, Jane began to cry. "The crown is not my right and pleases me not," she told the assembled group. "The Lady Mary is the rightful heir." However, the combined forces of Northumberland and her parents convinced her that not only had the king basically commanded her to take over, but that it was her duty as a faithful Protestant to keep Catholicism from regaining power over the royal throne.

Lady Jane Grey never really wanted to be queen

As quoted in Lady Jane Grey, Jane later told Queen Mary that, upon hearing she was to succeed Edward VI, she prayed to God that she would do it only "if what was given to me was rightly and lawfully mine." How much of this reflects what actually happened at Northumberland's Syon House on July 9, and how much was careful phrasing in front of a potentially vengeful monarch isn't totally clear. However, it's safe to say that Jane was probably reluctant to take such a visible role in a time of great religious and social upheaval.

Jane may have also agreed to become queen in order to keep others away from power. She was already a well-educated young woman and could very well have seen that the Duke of Northumberland meant for her to be a simple pawn in his quest for power and influence. As The Sisters Who Would Be Queen points out, she must have known that her father-in-law wanted her to make her husband and his son, Guildford, king of England. Being father to the king would have made Northumberland potentially even more powerful than he was when acting as Lord Protector for Edward VI. Whether or not that's true or a rumor handed down through the ages, it's possible that Jane agreed to take the crown to curb some of his influence.

Jane proved to be stronger than anyone expected

Surprisingly, Jane showed signs that she wouldn't easily become Northumberland's puppet. Take the matter of her young husband, Guildford. Most people expected that Queen Jane would make Guildford her king. Since he was the son of Northumberland, that would put the duke in a pretty nice position, politically speaking.

But, if everyone expected Jane to simply roll over and do what everyone told her to do, they were pretty surprised. As Lady Jane Grey reports, she pretty quickly decided that Guildford wasn't going to be king right away. Jane said that she would be happy to make her husband a duke but, as she later told the Dukes of Arundel and Pembroke, Guildford was pretty much never going to be king if she had anything to do with it. He'd had to be content being the Duke of Clarence and a royal consort instead.

Unsurprisingly, this caused a fair amount of strife. Jane's mother-in-law, the Duchess of Northumberland, was reportedly furious upon learning that Jane had a spine, after all. She told Guildford to stay away from his own marriage bed and to come back home to Syon House, but Jane, perhaps starting to feel a bit of the royal power, commanded Guildford to stay with her court instead. Guildford, for his part, tried to pretend he was king, such as when he tried to take charge of council meetings, but it was clear he was rather weakly swiping at control.

At least Lady Jane Grey approached her quickie coronation in style

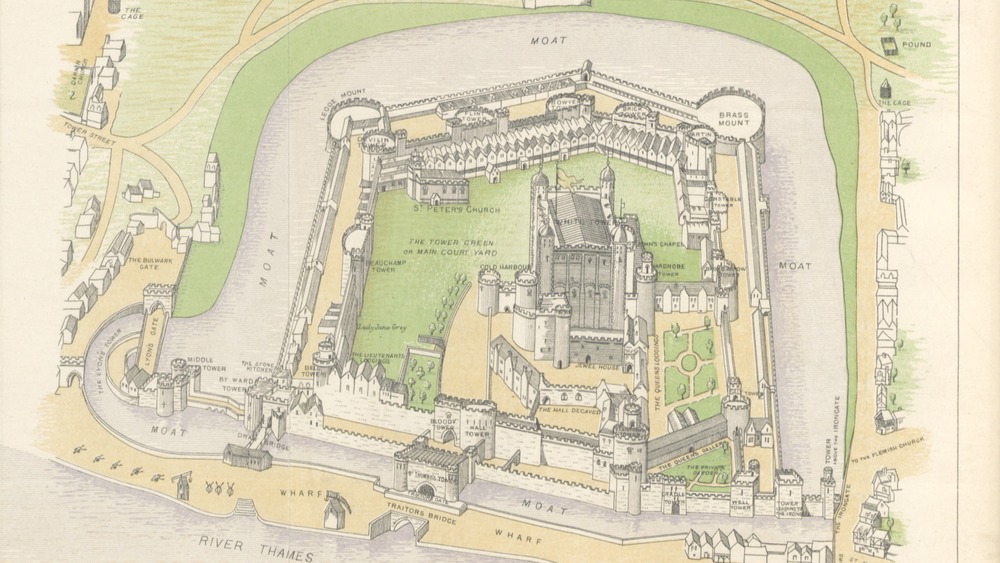

The day after she was told she was Queen, Jane and her small court entered the Tower of London, as was traditional for monarchs between their accession and coronation. Jane was dressed in a richly decorated gown, according to Historic Royal Palaces. She was decked out in a green velvet dress with gold embroidery and a long train, carried by her mother, Frances. Jane wore a white headdress, though you may not have noticed its color given all of the jewels sparkling there. In fact, Jane must have glittered thanks to all of the rubies, diamonds, pearls and gold that had been laid upon her. She also walked beneath a canopy, while Guildford walked beside her, apparently not too proud to do so despite the fact that he still wasn't king.

When it came time to try the crown on her head, however, Jane balked. According to The Sisters Who Would Be Queen, later interpretations of this scene liked to paint Jane as still shy, still reluctant, shrinking away from the heavy crown presented to her. Then again, she was already signing documents as "Jane the Quene". Perhaps the suggestion that Jane might want to have a crown made for Guildford was what caused her to pause, given that they were in the midst of a family fight over who, exactly, would rule England. It was to be a moot point, anyway. Officially, Jane was never crowned.

Mary Tudor put Jane into the Tower of London

While Jane was trying to navigate her sudden new job as Queen of England, another woman was preparing her own counterargument. Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VIII, was shocked to learn that her younger brother had skipped her over in the line of succession for some, in her opinion, piddling cousin. For Mary, the matter of Jane's Protestantism was also alarming. As a lifelong Catholic who was horrified by her own father's break with the Church, she was determined to take the throne and bring some old-fashioned religion back to England.

Because of her royal pedigree and, for some, in spite of her Catholicism, Mary was able to garner enough support to defeat Northumberland's scheme. Ultimately, as History reports, it all came down to numbers. Most of England's people supported Mary, arguing that the throne was rightfully hers. While Northumberland quickly left to suppress Mary's forces, the Royal Council suddenly reversed position and declared him a traitor. Mary was now the official queen and Jane was in a lot of trouble.

Northumberland's army soon dwindled to pathetic numbers as his men deserted him. He was captured on July 20, the same day that Lady Jane and her young husband were promptly put into the Tower of London. As per The Tudor Society, Northumberland was executed on August 22, 1553. Meanwhile, Mary finally got what she wanted when she was crowned on October 1.

Lady Jane Grey almost avoided execution

For a while, it seemed as if Jane and her husband, Guildford, might just escape the headsman's ax. After Mary took power, the pair were imprisoned in the Tower of London, sure, but they weren't executed posthaste like John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland. Rather, as History Extra reports, they were put on trial for treason and condemned, but then told it was only a formality. "It is believed Jane will not die," wrote one contemporary.

Mary apparently didn't want Jane or Guildford killed, perhaps hoping that she could marry and produce an heir that would negate Jane's claim to the throne. Yet, even with Jane locked away in the Tower, a rebellion nearly toppled Mary anyway. As per the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the Wyatt Rebellion of early 1554 put real fear into Mary and her supporters. Sir Thomas Wyatt led a group of rebels into London after Mary committed to wed Prince Philip of Spain, a foreigner and Catholic. Jane's father Henry was one of the rebel leaders.

That pretty much sealed Jane's fate, as she stood to remain a Protestant figurehead. As long as she was alive, Mary and her council reasoned, rebels would organize around her. It also didn't help that Jane had reportedly written an open letter condemning the Catholic mass and telling Protestants to "return again unto Christ's war."

Lady Jane had to watch the aftermath of her husband's execution

Lady Jane and her husband were both executed by order of Queen Mary on February 12, 1554. Guildford Dudley went first, according to Historic UK. Though Jane didn't have to attend her young husband's execution, his body was taken past her lodgings just as she was walking out to her own doom. The Sisters Who Would Be Queen says that Jane reportedly greeted this sight by exclaiming, "Oh! Guildford! Guildford!" before collecting herself. This fate was nothing, she told her husband's remains, "compared to the feast that you and I shall this day partake of in heaven!"

On Tower Green, Jane ascended the scaffold in a plain black dress. As she addressed onlookers, she admitted that she had taken part in unlawful actions, but told them that "I do wash my hands thereof in innocence." She concluded by reiterating her Protestant beliefs, saying, "I look to be saved by none other means, but only by the mercy of God in the merits of his only son, Jesus Christ," perhaps taking one final dig at the Catholic belief in good works.

She remained composed, Lady Jane Grey relates, except for a brief moment where, blindfolded, she could not find the block where she was to lay her head. She then said, "Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit," and was dispatched in quick order, only 16-years-old and forever remembered as the half-legitimate Nine Days' Queen.