What It Was Like Working At Studio 54

Studio 54 defined clubbing, disco, and celebrity in the late 1970s. The New York City discotheque attracted the famous, the infamous, and the notorious, plus tons of nobodies who were desperate to party with the celebs. It was a haven of illicit sex, illegal drug use, and the wildest parties the city had ever seen. Everyone wanted to get in, from ex-first ladies to drag queens.

But successful businesses don't just happen. There was an army of people working behind the velvet rope, behind the bar, and behind the scenes to make sure Studio 54's patrons had the times of their lives once they were inside. Some were serious businessmen and women who crunched numbers and made phone calls, and some were just mostly naked hot young men who wandered around the club hanging out with partygoers who weren't on the payroll. But together, the employees made it work.

Until they didn't. The original Studio 54 closed in 1980 after just three years as party central. But as the director of a documentary on the club said, "For something that was so brief, Studio 54 had a disproportionate impact on the people who went there." And the people who worked there. This is what it was like to work at Studio 54.

The Studio 54 doorman was all-powerful

To get into Studio 54, first you had to get past the doorman, Marc Benecke. His position as the gatekeeper made him socially the most powerful man in the city, according to no less an authority than The New York Times. He was all of 19-years-old.

He also had zero experience as a doorman or even with the club scene. Benecke wanted to be a lawyer, according to the Edition Broadsheet. But he had a distant cousin who was hired to be bouncer at Studio 54, and after having lunch together one day, they wandered over. Club owner Steve Rubell asked him what he was doing for the summer and hired him on the spot.

Perhaps it was the blank slate Benecke offered that Rubell liked. In any case, the owner taught him everything about how to get a great mix of people in Studio 54 every night. While celebs were always let in, anyone could make it past the velvet ropes if they were fabulous enough. Benecke said, "One of the things I think that made me a good doorperson was that I can really feel [people's] energy and for the most part, where they're coming from." He could also be a jerk though. If he was never going to let you in, he'd ignore you, or worse, mess with you. Once he told a guy to go to Bloomingdale's and buy the same blazer Benecke was wearing. The man did, but the doorman still didn't let him in.

The coat check girls had a prime spot

After making it past the velvet rope, partiers at Studio 54 entered what one hostess called "The Corridor of Joy," according to Another Man. It was decorated with "crystal chandeliers, carpet, and mirrors," filled with the delighted screams of people seeing it for the first time, and drew patrons to another set of doors to the club proper. But before you went in there, you had to check your coat. Enter the coat check girls.

As part of partiers' first impression of the club, the coat check girls had to fit in. Caravan to Oz says they were picked for "their beauty, youth, energy and style." Being young, pretty, and in New York City, this of course meant a lot of them were wannabe actors and singers.

The all-night shifts were "grueling and the work was extremely physical" and had some occupational hazards, namely accidental contact highs. There were so many poppers left in people's coats, the women often got high by accident when they exploded. Regardless of their physical state, it was the coat check girls' job to play it "cool" no matter how famous the star or how drugged up the person who lost their ticket was. Sometimes the stars would even come hide out in the coat check room to relax a bit outside of the craziness of the club. The girls could also go hang around the club themselves for a bit, then come back with all the gossip.

Studio 54 bartenders were half-naked beefcakes

The bartenders at Studio 54 were meant to be eye candy as much as employees there to serve drinks. Exclusively men, it's unclear if any of them owned a shirt. Their uniform was apparently various stages of undress. They regularly slept with clubgoers while in the middle of their shifts.

One bartender stood out for being a bit different. There are varying stories of how Scott Taylor was hired, but New York Magazine says he just showed up on opening night and asked for a job. By the next night, he was put behind the bar when another guy called in sick. (Calling in sick on your second night of work is very Studio 54, though.) While the other bartenders danced at the end of the night, he took out the trash and swept up. Perhaps because, as Taylor put it, "Steve [Rubell] wanted all big, gay, muscle-bound bartenders, and I was, like, this Jewish straight boy from Queens," the owner was unimpressed when he noticed and tried to fire him. But the fact Taylor did work while the other bartenders partied made him invaluable to his coworkers, and they demanded he stay.

One Studio 54 bartender went onto much bigger things. Actor Alec Baldwin told Interview he worked there for two months in the fall of 1979. He talked about working on the balcony, only to be sent to "fetch cigarettes" so people could use it to hook up.

"Lenny 54" got paid to party

For one person, even the tiny amount of work expected of busboys and bartenders at Studio 54 was too much. According to New York Magazine, Lenny Miestorm was a teenaged art student who grew up on a farm and one of the original hires at Studio 54. But, like so many creatives, he found such a traditional job confining and decided he had a better idea, which he presented to the club's owner after less than one shift. "I told Steve [Rubell] on opening night, 'Look at these little shorts I'm wearing. Do you expect me to pick up glasses and sweep the floors? I'm not going to do that. I'm going to entertain your guests.'"

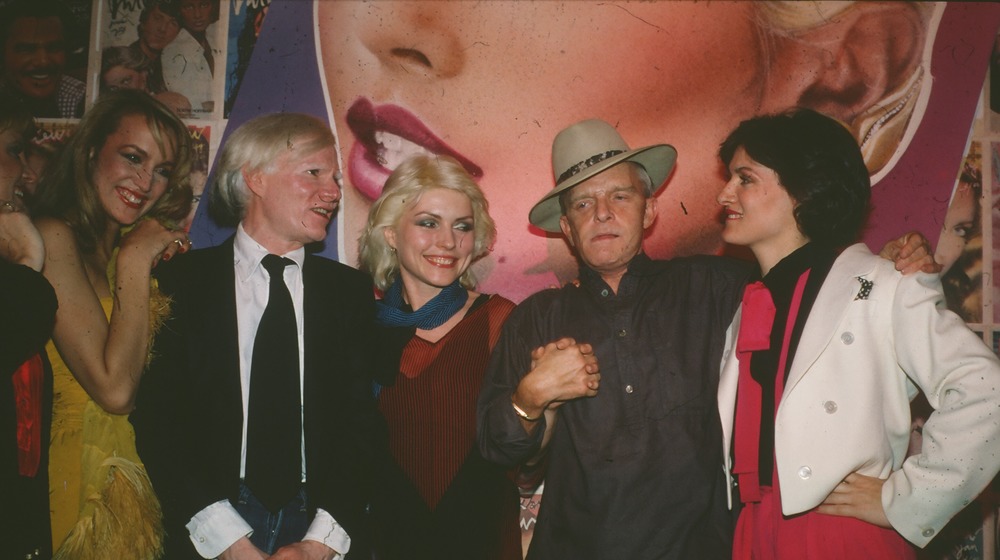

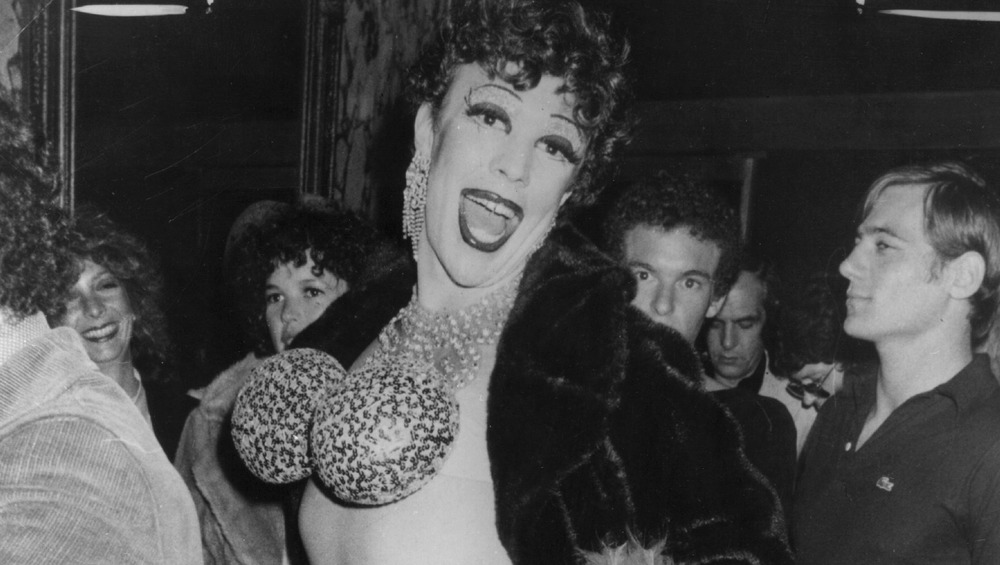

Instead of informing this nobody that there were a million young, attractive men in New York City who would kill for his job, Rubell decided this was a great idea. And, perhaps to make Miestorm more entertaining, he also gave him his first quaalude. Miestorm claims that later that same evening, he "snorted coke with Andy Warhol, Divine, and Halston."

This scheme to get out of real work, well, worked. Miestorm, who got the nickname "Lenny 54," got the best job in the world — a paid partygoer. That's right, he still got a regular paycheck, just to hang out and do drugs with celebrities. (The downside — the drugs became a serious problem until he finally realized years later he needed to sober up.)

The celebrity wrangler brought the star power

Shortly before Studio 54 opened, Joanne Horowitz met owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager at their other club, Enchanted Gardens. According to The Hollywood Reporter, she basically created a new job when she mentioned to them she had a subscription to Celebrity Bulletin, which, in the days before the internet was how one found out where celebs were staying. She sent out some invites, and opening night saw big names like Cher, Henry Winkler, JFK Jr., and Warren Beatty show up. The next day, a picture of Cher leaving the club covered the New York Post. Realizing you really could pay for publicity like that, the job of celebrity wrangler was born.

Horowitz's whole gig was getting famous people to come to the club and booking movie premieres there. She became friends with Michael Jackson, wore $1,200 shoes, and took limos to the disco at midnight every night. (She'd made a deal with the limo company that if she recommended them to celebs, she could use them for free.) Each celebrity "get" was worth a certain amount of money, depending on star power. The scale went from $30 to $250 (she told New York Magazine Alice Cooper was worth $60 while Sylvester Stallone was $80), with $250 bonuses if pictures of the stars at Studio 54 made the papers.

As of 2016, Horowitz was still working with celebrities as ... Kevin Spacey's manager, a job she held for 28 years, until he fired her.

Studio 54 DJs got no respect

Considering Studio 54 was a nightclub, and people tend to go to nightclubs to dance, you'd assume the DJs there would be close to royalty. They spun the tunes that got all the very drugged-up patrons on the dancefloor, after all. And the two resident DJs, Nicky Siano and Richie Kaczor, were indeed two of the best. According to The Vinyl Factory, Siano was "one of the most renowned DJs in New York at the time" and "his technique on the decks helped further the art of mixing records as we know it." Yet for some reason, the owners treated them like they were an inconvenience.

Siano claims, "Steve [Rubell] wanted an invisible DJ, so that it wouldn't interfere with the club." How exactly the music at a disco could interfere when it's literally called "disco" is unclear. Nevertheless, they were "treated like s***." They had to go against everything they knew about DJing to follow the strict rules the owners had. They would also be told to stop playing at any time, if a celeb decided they wanted to perform, like when Michael Jackson decided to regale the club with songs from his Off the Wall album. Then there were the celebrities who used the DJ booth as a place to hang out, getting in the way of the records and making Siano and Kaczor's job impossible.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Siano only lasted four months at Studio 54, but Kaczor stuck it out for three years.

Some people actually worked hard

Not everyone who worked at Studio 54 was just there to have a good time. There were the front of house employees who danced around with the celebrities, then there were the people on the business side behind the scenes, who actually worked a real job to make the club a success.

Michael Overington, the club's general manager, explained to New York Magazine, "Maybe a few busboys like Lenny [Miestorm] partied, but the doormen, the people who dealt with money, the technical people handling sets in the back, they didn't party. We were all there to work really long hours. And we all made really good money. It's almost like asking the cast of a major show like A Chorus Line, 'Well, did you guys really go out and party all the time?' No. We were all really serious about creating a great show."

There were people like Carmen D'Alessio, who claims almost all the credit for making the club a hit but didn't hang out with the other employees, saying that, "Studio didn't impress [her]." Or Myra Scheer, who went from clubgoer to the owners' right-hand woman. Chuck Garelick was head of security, a serious job when a mob of wannabe cool people were constantly clamoring to be let in, sometimes resorting to threats of violence. Even R. Scott Bromley, the architect who designed the indoor space, did the hard work actually hammering it all together.

Studio 54 owners were polar opposites

The owners of Studio 54 became as well-known as the celebs who partied there. According to Disco, Drugs & Decadence: The Rise and Fall of America's Premier Discotheque, Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell had known each other since they were college students and had been in business before Studio 54, including as co-owners of another New York City nightclub called Enchanted Garden.

It wasn't their idea to open a new disco. A German male model, Uva Harden, originally found the location and brought on an investor plus a woman named Carmen D'Alessio to handle the publicity. When the original investor bailed, D'Alessio recruited Schrager and Rubell, who managed to essentially buy the idea off Harden for a few thousand dollars, making the project theirs and theirs alone.

The two men were very good friends, despite being incredibly different personalities. Schrager was all business, happy to stay behind the scenes and run things that way. He was so elusive, he was often described as a "silent partner" in the business. Rubell was the exact opposite. What good was owning the coolest club in the world if you didn't party in it yourself? He mixed with the celebs and partied just as hard as they did. Rubell was also rumored to pressure the young men he employed to sleep with him if they wanted to keep their jobs. Somehow, the pairing worked, and when Rubell died in 1989, Schrager said, "I'll never have that kind of friend again."

Everyone at Studio 54 was having sex with everyone else

All the beautiful people dancing and doing drugs of course led to sex. The club was even planned with that in mind. According to The Guardian, the balcony, with its slightly secluded nature, was covered in easy to wipe down materials for any body fluids that got spilled up there. For even more privacy, there were mattresses in the basement, but assumedly the employees weren't cleaning those every night. The former editor of Interview, Bob Colacello, said of Studio 54, "Even if you weren't having sex with someone every night, you felt like you could."

This included the employees. The busboys were running around in tiny shorts, for goodness sake. But the person who almost certainly got the most offers for sex was the doorman Marc Benecke, when people offered up their bodies just to get inside. According to The Independent, he said that he "sometimes" took them up on it.

Tragically, the danger of crazy sex in the late 1970s became abundantly clear in the 1980s. While there's no way of knowing if Studio 54 contributed to the AIDS epidemic in any real way, many regular clubgoers and employees would succumb to the disease. Scott Bitterman, a former busboy and assistant manager, wrote on his blog that notorious attorney Roy Cohn and fashion designer Halston died from AIDS complications, as did the club's host Joe Renny, and even owner Steve Rubell, in 1989.

How to work your way up at Studio 54

Jobs at Studio 54 were extremely fluid. According to interviews with various ex-employees in New York Magazine, many of the people the owners hired seemed to have simply walked in and offered their services or met them through a friend. In most cases, there was no serious hiring process, and many employees had no relevant experience or, indeed, any experience whatsoever before they were tasked with running the world's most amazing club.

Once you were in, you could find yourself doing a million different jobs or getting a sudden and unexpected promotion. Scott Bitterman started bussing tables, but that wasn't where he stopped. According to his website, for over two years he "did everything from bussing tables to running the front desk, to counting cash (lots of cash), to managing the third shift during Studio 54's first renovation, to creating and running 'auditions' for new staff, to initiating and designing special decor for the basement VIP area."

Michael Overington was another example of how far you could go at Studio 54. He started out as a janitor earning $3 an hour and worked his way up to becoming the club's general manager.

The whistleblower that brought Studio 54 down

Every party has to end sometime, even one as awesome as Studio 54. In this case, it was one of their own employees that shut it down. You see, Studio 54 wasn't just a place where illegal sex and drugs happened. The law was willing to look the other way on that stuff. But screwing the government out of their money? Absolutely unacceptable.

It was a pretty open secret that Studio 54 had super shady bookkeeping (owner Steve Rubell said to a reporter that "only the Mafia does better"), and it was an all-cash business. This made it easy for the owners to skim profits, but they didn't take just a little bit off the top — they took everything else and just left that little top bit. According to a prosecutor (via MarketWatch), the owners were skimming up to 80% of the club's revenue.

Since everyone knew, at least vaguely, what was up, this made it easy for an unhappy employee, mad about his treatment by the club, to squeal to the feds. The director of a documentary on Studio 54 said, "A disgruntled employee knew about the skimming operation and where the cash was hidden in the club. He tipped off the IRS and the IRS pounced." The employee's tip would lead to prison sentences for the owners, and the club closed. (It would open again with new ownership, but it wasn't the same.) The employee still remains unknown.