The Crazy True Story Of William Randolph Hearst

Media empires controlled by one rich and powerful man who has political ambitions and no problem with fake news sounds like a very modern drama. But William Randolph Hearst was born in the middle of the American Civil War.

WR — as his mistress called him — had a highly educated mother with equally high standards, and a father who had ambitioned his way from Missouri mining school to mine owner, rancher, Senator, and millionaire. At first, WR had the drive to live up to his family's expectations. Turning around one family newspaper paved the way to a media empire, and he celebrated his fame by constructing a dream castle on the California coast.

But like his political goals, his central romantic relationship and his status as the newspaper king, the castle never completely matched his ambitions. This is the crazy real life story of William Randolph Hearst's rise to glory, crash landing, and the movie he hated that cemented his fame.

William Randolph Hearst inherited his cunning from his father

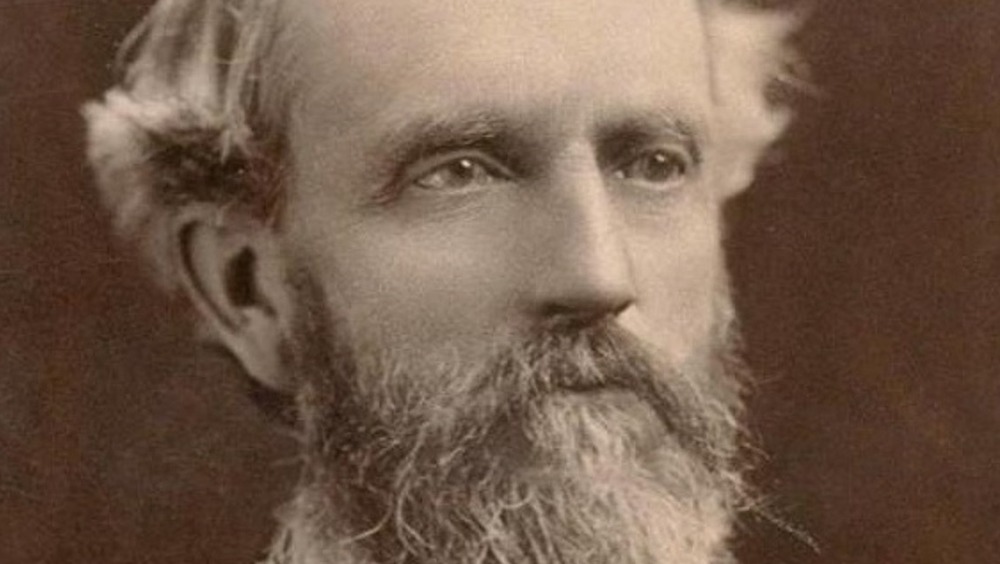

To understand William Randolph Hearst's unquenchable desire for power, look at his father George. Unlike his son, George Hearst was born to relatively humble origins, in Franklin County, Missouri, in 1820. But like his son, George used his sharp wits to improve his own position within the world that was accessible to him: in his case, mining.

According to his official U.S. Congress biography — note the foreshadowing — when he was 18, George graduated from the Franklin County Mining School. He weathered a few setbacks, but eventually made a series of investments in some of the most successful mines in the country. He also bought ranches in California, including the land that his son later used for his famous home, San Simeon, between San Jose and Los Angeles.

Having spent some of his self-made millions funding other aspiring political candidates' campaigns, George decided to go after political power himself. In 1865, three years after moving to San Francisco, he was elected to the State Assembly as a Democrat, but failed to get re-elected after he voted against the 13th Amendment (outlawing slavery). He lost a campaign for governor in 1882, but four years later, Congress appointed him to fill a Senate seat left open when its former occupant died. George was elected in his own right in 1887, but died before his first term was up, in 1891.

William Randolph Hearst was kicked out of Harvard before it was cool

The only child of a millionaire and a doting young mother, William Randolph Hearst grew up spoiled with material goods and attention. George Hearst married Phoebe Apperson in June 1862 during a temporary return to Franklin County. He was 41 and she was 19. Phoebe became pregnant during their move to San Francisco, giving birth to William Randolph on April 29, 1863.

Known as Willie, William Randolph displayed political savvy and a keen intellect from a young age. At least his mother thought so. According to biography William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910, he loved to read and to understand machinery, used his father's money to impress his peers, and pulled pranks involving setting small animals loose at inopportune moments.

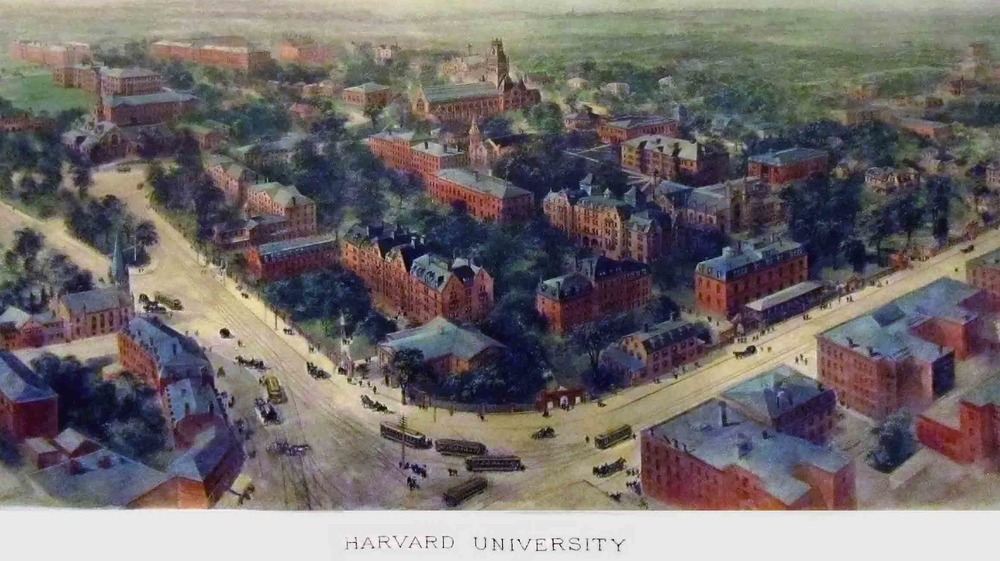

In 1882, William Randolph enrolled at Harvard. He enjoyed his first year, but as a sophomore he started getting distracted. He was famous for his parties, enthusiastically participated in various clubs, wrote for humorous student paper the Lampoon, and took part in political campaigns. In 1885, having already been put on academic probation, William Randolph was dismissed after he threw several disruptive parades in support of Grover Cleveland's successful presidential bid. The suspension was initially temporary, but William Randolph lost any remaining good will among the faculty when he sent the professors who had voted to suspend him chamber pots with their own pictures and names printed at the bottom.

William Randolph Hearst got his first newspaper job from his father

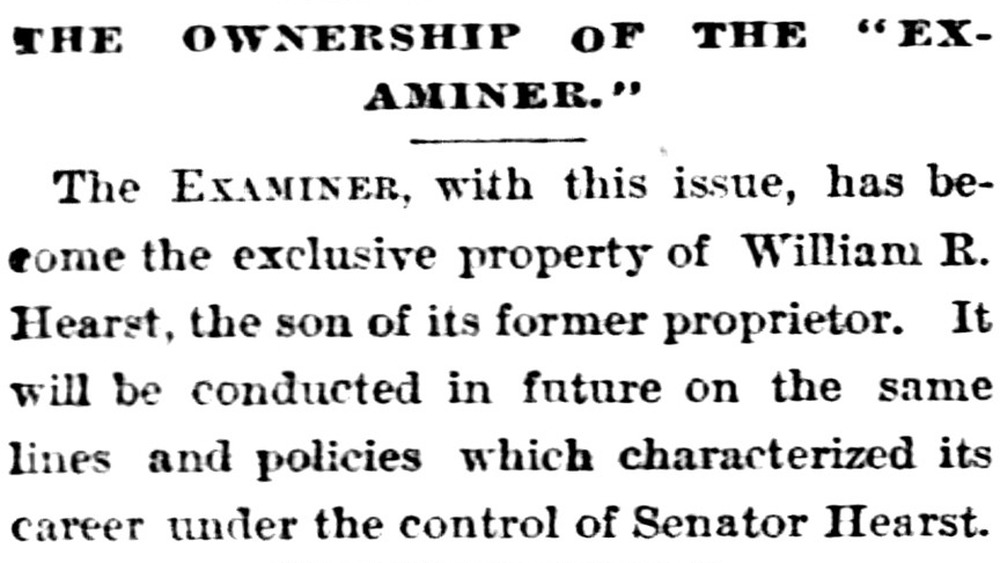

Being ejected from Harvard turned out to be a blessing in disguise for William Randolph Hearst. In 1886, the year his expulsion became official, he got a job as a reporter for the New York World, which was headed by Joseph Pulitzer. He studied how the newspaper was run and what made a popular story. The following year, he persuaded his father to put him in charge of a newspaper the older Hearst had bought to further his own political career: the San Francisco Examiner. As the San Francisco Examiner itself reported in 2015, the rumor was that George had acquired the paper in a poker game.

According to William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910, George wanted his son to follow him into mining or ranching, which he felt would be more lucrative. But William Randolph showed a remarkable aptitude for regenerating the struggling newspaper, borrowing (or stealing) tricks he'd learned from his time at the World. As the Nation explains, he gave his working class readers — many of whom could barely read or didn't understand English — what they wanted: easy-to-understand, attention-grabbing headlines accompanied by graphic illustrations. He focused on scandals and crimes, knowing these were irresistible to readers looking for entertainment over information. If the facts of a story weren't interesting enough, he ordered his team of writers to embellish them.

William Randolph Hearst had a major feud with Joseph Pulitzer

Turning around the fortunes of the San Francisco Examiner was just the beginning for William Randolph Hearst, who saw himself heading a national media empire. To kickstart that plan, in 1895 he turned his attention east, purchasing the sinking New York Morning Journal for just $150,000 (about $4.4 million today.)

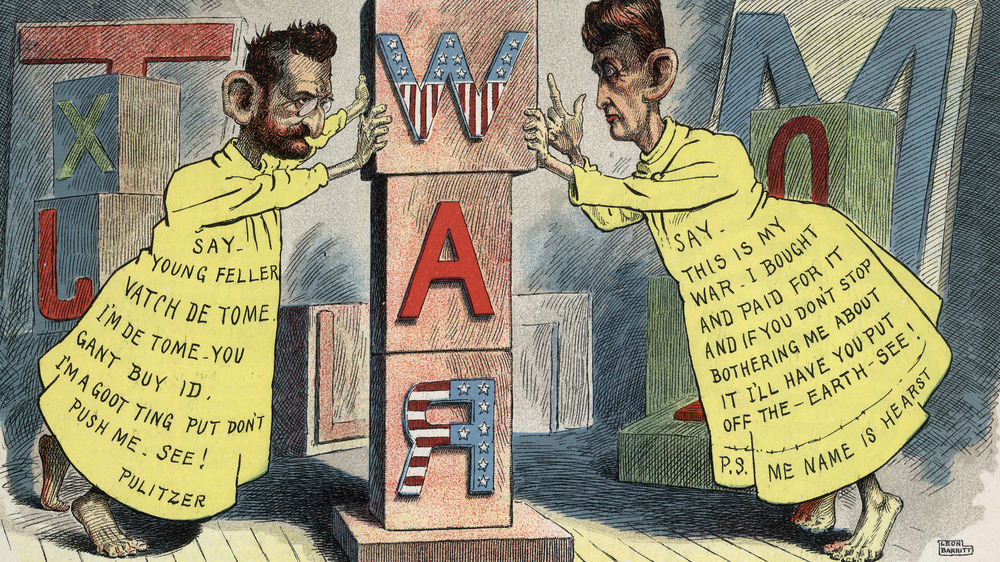

Gossipy, light-hearted, and cheap, the Journal was founded in 1882 by Albert Pulitzer. According to The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst, Albert was deeply jealous of his more famous older brother Joseph, who had started the nationally esteemed New York World a year later. But Hearst was undaunted by the older Pulitzer's reputation as a brilliant newspaperman, and set about directly challenging the World's dominance. Hearst deployed all his usual tricks, including cutting prices and publishing shocking and embellished crime stories. He also hired away some of Pulitzer's most talented staff, including Morrill Goddard, managing editor of the World's Sunday edition, and cartoonist Richard F. Outcault.

Outcault drew a popular comic for the World called Hogan's Alley, with a character called the Yellow Kid. After he defected to the Journal, Pulitzer hired another cartoonist to draw a different Yellow Kid, leading to people describing the pair's escalating circulation war as "yellow journalism." Whyte writes that the two men were forced to call a truce in 1898 when their competition over the Spanish-American War threatened to bankrupt both papers.

William Randolph Hearst fueled American support for the Spanish-American War

For all of the sensationalism William Randolph Hearst cooked up at the Journal — and for all the sensationalism he provoked at Pulitzer's World in response — one of the most infamous charges attached to his legacy has ironically been sensationalized itself. The story goes that when an illustrator Hearst had dispatched to Cuba to cover a simmering rebellion against Spanish rule wrote back that there was no sign of war in 1898, Hearst cabled him a reply that read: "You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war." However, as the BBC explains, Hearst denied this and there's no evidence that the message ever existed.

Historians today point out that the U.S. and Spain had been getting closer and closer to war over the latter's harsh colonial rule in Cuba for most of the 19th century. Hearst's and Pulitzer's inflammatory reporting during the 1890s played into these existing resentments — it helped them sell papers, after all — but didn't create them.

However, both men's newspapers were quick to blame Spain — with no evidence — for an explosion that sank the U.S.S. Maine in the Havana harbor on February 15, 1898. Although official reports did not directly implicate Spain, public sentiment that was partly driven by the media saw the U.S. officially declare war on Spain that April. Ironically, the costs of the Journal's and World's sensational coverage of the Spanish-American War nearly sunk both papers.

William Randolph Hearst failed to get far in politics

Perhaps surprisingly, William Randolph Hearst was a progressive Democrat — at least early in his life. According to The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst, he believed in labor reforms, including the right to collective bargaining, a graduated income tax in which the proportion of tax a person pays is based on their income, and other reforms deemed radical for the 1890s and early 1900s.

But Hearst wasn't afraid to break with his party's expectations. In 1896, Hearst made his papers the only national chain to endorse radical Democrat William Jennings Bryan for President. Hearst also used his papers to attack Republican candidate William McKinley, even including "jokes" about assassination. McKinley won the Presidency, but was assassinated in 1901 during his second term, which led to backlash against Hearst.

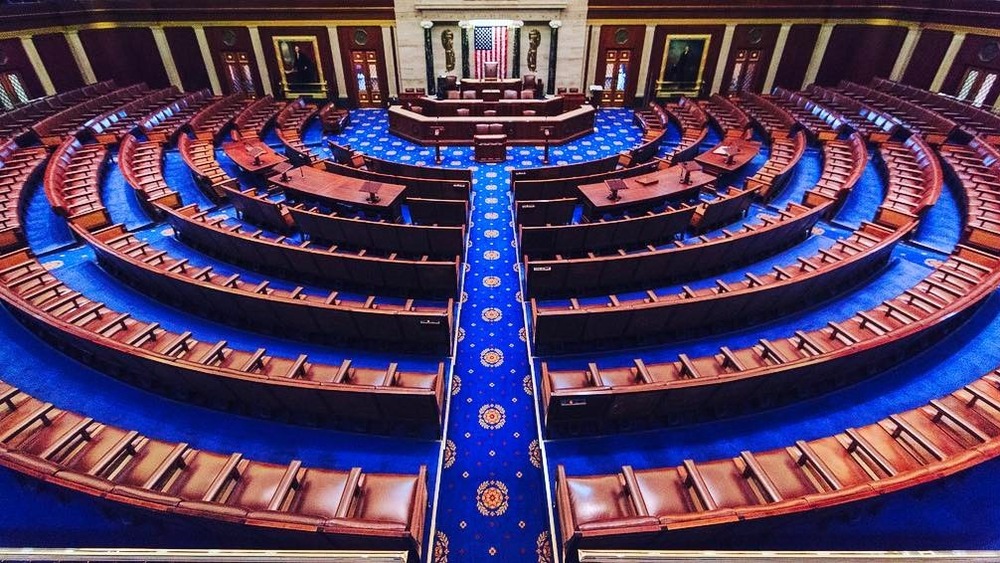

After Bryan's repeated losses, Hearst himself stepped into politics. He unsuccessfully ran for President as the anti-establishment Democratic candidate in 1904, for mayor of New York in 1905, and for governor of New York in 1906. He had the most success with the House of Representatives: he served in the House from 1903 to 1907 on behalf of New York's 11th congressional district, but missed an almost impressive 196 of 223 roll call votes during his two terms. In 1908, he formed his Independence Party, which leaned Democratic while also challenging many of the party's policies from the outside.

William Randolph Hearst had a famously scandalous love life

At least scandal-selling William Randolph Hearst practiced what he zealously reported. In 1903, two days before his 40th birthday, Hearst married 21-year-old showgirl Millicent Veronica Willson in New York. The couple had five sons between 1904 and 1915, but their relationship was more of a political arrangement than a true romance. Millicent's mother was rumored to have seedy connections to the Democratic seat of power in New York (as the LA Times reports) while Hearst gave socially ambitious Millicent access to the wealthier classes.

According to the New Yorker, Hearst first saw the woman who would become his most famous romantic partner, chorus girl and actress Marion Davies, in 1915, when he watched her perform in a Broadway show. As a Catholic, Hearst was staunchly opposed to divorce, but that didn't stop him and Davies from carrying on a very public affair, starting around 1917 when Davies was 20 and Hearst was 54. Two years later, Hearst co-founded movie studio Cosmopolitan Pictures, casting Davies in many of its projects and later naming her company president.

Hearst and Davies started openly living together in California from around 1924, which proved too much for Millicent. She stayed in New York, outliving her estranged husband by 23 years and dying aged 92 in 1974, the New York Times reports.

William Randolph Hearst built himself a California castle

In 1919, William Randolph Hearst's mother Phoebe died, and he inherited the wealth his father had built up through his mining endeavors. As the New Yorker reports, before this, Randolph was only rich on paper. The media empire he'd always dreamed of had put him into debt. In addition to George Hearst's money, he inherited the California ranch known as San Simeon, which had gradually been expanded to include neighboring properties until it covered 250,000 acres.

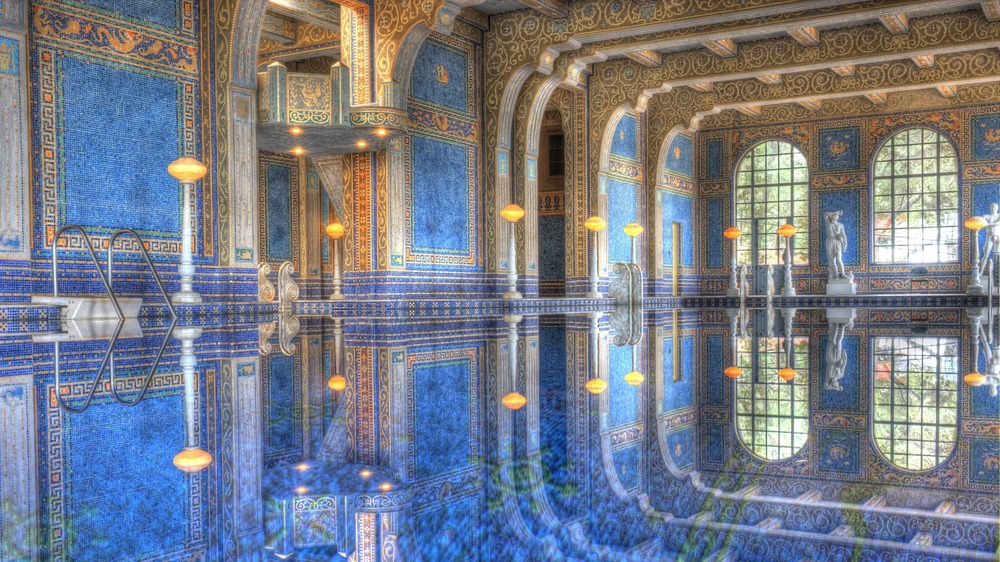

William Randolph poured his newfound riches into building a glorious estate, which he called La Cuesta Encantada (the Enchanted Hill), but which would later be known as Hearst Castle. He hired San Francisco-based architect Julia Morgan to achieve his vision of an enormous, elaborate palace with multiple guest houses that would also feel welcoming to his many visitors. The house beautifully combines a blend of influences, including Spanish Gothic, Roman baths, Venetian palaces, and religious motifs. Hearst also collected art and animals, the latter of which lived in his private zoo on the grounds.

The project proved too ambitious in the long run. Hearst Castle was never finished, and construction ended in 1947 when Hearst became too ill to travel there from his main home in Beverly Hills. He died four years later, and in 1954 his family donated the castle as a National Park, which receives 850,000 visitors a year, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

William Randolph Hearst knew how to throw a party

Even if you're not interested in architecture and free-range zebras, an invitation to Hearst Castle would have been hard to turn down: William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies were famous for their parties.

Davies has been lumbered with an unfair reputation as beautiful but ditzy, thanks to a character based on her in Citizen Kane, but according to the New Yorker, she was known among guests for being warm and funny. After staying at San Simeon in 1929, Winston Churchill wrote to his wife Clementine: "were all charmed by her. She is not strikingly beautiful nor impressive in any way. But her personality is most attractive... She asked us to use her house as if it was our own."

There were dinner parties every weekend the couple was in town, as well as Christmas and birthday parties and themed masked balls. While they were a lot of fun, Hearst had rules. The New Yorker writes that Davies struggled with alcoholism, and Hearst controlled how much alcohol guests could drink. You were allowed two pre-dinner cocktails, followed by wine at dinner, but not too much. After the meal, Hearst would show a movie, a habit that was quickly picked up by other Hollywood hosts. During the day, guests were free to explore San Simeon, but in the afternoons, Hearst liked to corral them into horseback riding for hours, or other sports.

William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies may have had a love child

William Randolph Hearst and his wife Millicent gave their five sons names that are confusingly similar to each other and their ancestors'. The oldest was George Randolph, followed by William Randolph Hearst Jr., John Randolph and twins Randolph Apperson and David Elbert Willson (later Whitmire.) To make it even harder, those sons then passed many of these similar names to their own children.

All five sons went into media jobs, including into various positions within the Hearst corporation. But William Randolph Sr.'s most famous relative is his granddaughter Patty Hearst, daughter of Randolph Apperson, who gained national fame in 1974 when she was kidnapped by and temporarily defected to the Symbionese Liberation Army.

However, some believe that Hearst also had a secret daughter, Patricia Lake, with Marion Davies. Lake was always introduced as Davies' niece, but there were rumors that she was actually the couple's child. The LA Times reports that on her deathbed in 1993, Lake claimed that Davies had given birth to Lake in France and handed the baby to her sister and brother-in-law. She also said both Hearst and Davies later admitted to her that they were her biological parents. What is certain is that she spent a lot of time at San Simeon, and Hearst funded her lavish lifestyle until he died, leaving her a significant trust.

William Randolph Hearst eventually lost touch with his readers

When William Randolph Hearst first entered national attention, he was seen as something of a class rebel: a wealthy Democrat who nevertheless supported workers' rights while also understanding their need for unsanctimonious entertainment. But as Hearst aged and battled through personal and financial storms, he increasingly found himself on the other side of the political line from his working class readers.

In the mid-1930s, Hearst looked to be extremely well-off. According to a 1935 Fortune magazine article cited in American Heritage, his media empire had expanded to 28 newspapers and 13 magazines, eight radio stations, and two movie companies. He also had his art collection, two million acres of land and shares in a mine. But by then, Franklin D. Roosevelt had been elected President — with help from Hearst's readers — and he levied high taxes on the wealthy to fund his New Deal, designed to help the poor during the Great Depression. The Atlantic reports that Hearst not only viciously attacked Roosevelt as an anti-American Communist in his papers, he also published articles by Adolph Hitler. This earned him scorn and hatred from the public. After he was forced to sell some of his art collection, Hearst retreated into seclusion in the years before his death in 1951.

William Randolph Hearst tried to destroy Citizen Kane

Ironically, one reason William Randolph Hearst has remained alive in the public imagination is because he was immortalized in Citizen Kane. The debut feature of Orson Welles — who wrote, directed, and starred — the movie told the life story of a genius media mogul-turned-megalomaniac, who dies power-crazed, hated, and isolated in his huge Florida estate.

It was seen as a thinly veiled caricature of Hearst's life, and in January 1941, 77-year-old Hearst fought back against this fictionalized version of his story. He was most upset about the character that he thought represented Marion Davies, who was portrayed as a talentless actress and virtual prisoner in their vast home, and an alcoholic. Hearst's career in newspapers had taught him that attacking the movie would only bring it more attention. Instead, he banned his chain of papers from covering or advertising it. He had help from powerful friends, including gossip columnist Louella Parsons and MGM head Louis B. Meyer, who sent a representative/enforcer to offer George Schaefer — the president of RKO, which owned Citizen Kane — $800,000 to destroy all the negatives.

Schaefer declined, but the collective pressure saw theater chains refuse to show all but a handful of screenings. Welles and his co-writer Herman Mankiewicz still picked up a Best Writing Oscar for their screenplay, and the movie received eight other nominations. After Hearst's death, critics reevaluated the movie, and as Vulture explains, it's now regularly cited as one of the best of all time.