The Tragic Real-Life Story Of The Pulitzer Family

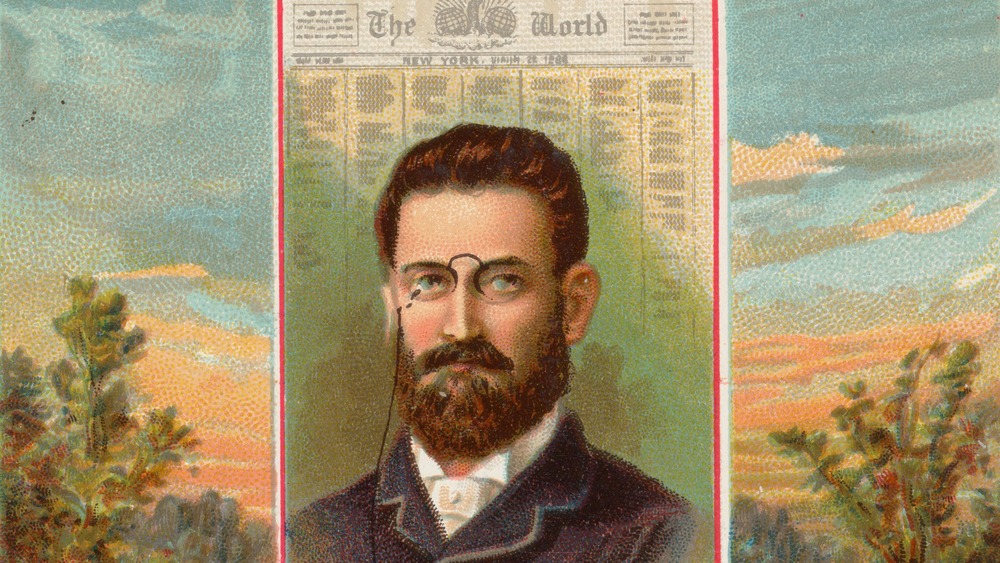

The Pulitzers were once the leading media family in the United States. A legacy started by Hungarian immigrant Joseph Pulitzer, Pulitzer founded the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, operated the New York World, held political office, and established the well-renowned Pulitzer Prize. For generations, Joseph Pulitzer's descendants enjoyed the prestige of being one of the most prominent families in the U.S.

Still, for all their fame and influence, the Pulitzers were not without their troubles. In more recent years, the family would be plagued by divorce, scandal, death, infighting, lawsuits, and business struggles. Not even the original scion himself, Joseph Pulitzer, would escape hardships involving his poor health and family members' premature deaths. And the Pulitzers would endure the hefty cost that fame brings a family in the spotlight — having their problems and personal issues broadcast to the world for all to see. This is the tragic real-life story of the Pulitzer family.

Joseph Pulitzer's father's business went bankrupt

Joseph Pulitzer was born in Makó, Hungary, to parents Fülöp and Elize Pulitzer. Fülöp Pulitzer was a very successful grain merchant, so wealthy that he was able to retire early. Growing up, Joseph and his brother were given many educational and economic advantages thanks to their father's wealth. Both boys were educated in private schools and by tutors and learned to speak both French and German. However, this life of luxury didn't last forever. After Fülöp passed away when Joseph was 11, the family business went bankrupt, according to writer James McGrath Morris. After Joseph turned 17, and his mother was safely remarried, he knew he had to make his own way in the world.

The teenage Joseph first tried to become a soldier and attempted to enlist in the Austrian Army, Napoleon's Foreign Legion, and then the British Army. All of these nations' armies rejected him due to Pulitzer having weak eyesight and overall fragile health. But he got his big chance when he happened to meet a bounty recruiter for the United States' Union Army — the U.S. was currently right in the middle of the Civil War. Pulitzer decided to take the recruiter up on the offer to head to the United States and join the Union Army — and legend has it that Pulitzer jumped ship on the way to Boston and swam to shore so he could keep the recruitment bounty for himself.

Joseph Pulitzer was broke when he first came to America

According to the Pulitzers' official website, Pulitzer did serve his time fighting on behalf of the Union Army in the American Civil War. Specifically, he was in the Lincoln Cavalry with many other German recruits (Pulitzer was fluent in German but not well-versed in English at the time). He was in the Cavalry for about a year before the war came to an end, and Pulitzer was honorably discharged.

All the same, his early years in the United States were hard-going. After leaving the U.S. Army, Pulitzer was without money or a place to live. He often had to sleep on park benches and scrambled to find work. When he didn't have any luck finding steady work in New York, he decided to head west to St. Louis, Missouri. Pulitzer managed to catch a train to Illinois but ran out of money and couldn't afford a ferry across the Mississippi River. He ended up striking a deal to shovel coal on the ferry in exchange for passage.

Pulitzer continued to get odd jobs in St. Louis, but he finally got his first big career opportunity while studying English at the library. As noted by the The State Historical Society of Missouri, Pulitzer made the acquaintance of Carl Schurz, the co-editor and part-owner of the German newspaper The Westliche Post. Schurz was impressed with Pulitzer's intelligence and command of the German language and hired him as a reporter.

Joseph Pulitzer shot a man

Besides being a newspaperman, Joseph Pulitzer also became a politician. He was nominated in and won a special election as a Republican in the Fifth District in St. Louis at only 22 years old. According to The State Historical Society of Missouri, Pulitzer felt strongly about fighting against corruption as a representative of his district. He deeply disliked the St. Louis County Court, which regularly practiced favoritism in hiring county officials and the courts' friends for building contracts. What Pulitzer wanted to do was abolish the court entirely and introduced a bill to do so.

One day, Pulitzer encountered builder Captain Edward Augustine, a known court friend who was receiving political favoritism in the form of building contracts. Pulitzer called him out, and Augustine retorted by calling Pulitzer a liar. Enraged, Pulitzer retaliated by getting his Army gun from his home and returning to shoot Augustine in the leg. Pulitzer did plead guilty for the shooting, but he got off by paying a hefty fine — which his friends helped him pay. Pulitzer's bill that called for the abolishment of the St. Louis County Court eventually passed.

Joseph Pulitzer was blind by his forties

Joseph Pulitzer had struggled with poor eyesight since he was a young man, but after years of working 16-hour-long days, he was almost completely blind by age 43. He also had other health troubles that started in his youth and progressively became worse. As noted by Harper's Weekly, such ailments included diabetes, rheumatism, and asthma. According to The State Historical Society of Missouri, Pulitzer also became so highly sensitive to noise to the point where he had to soundproof his bedroom and his yacht completely.

However, despite his worsening health and his doctor's recommendations, Pulitzer hadn't been deterred from purchasing the almost bankrupt New York World newspaper in 1883. Even after moving to New York, Pulitzer still got elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing New York's 9th District. He never returned to the newsroom again, but he still managed to run the paper by communicating with his secretaries using code in case anyone seized his messages.

Two Pulitzer children died young

Joseph Pulitzer and his wife Katherine Davis Pulitzer had seven children in total: Ralph, Lucille, Katherine, Joseph Jr., Edith, Constance, and Herbert. However, only five survived to adulthood — two of them died shockingly young. One of his daughters, Katherine Ethel Pulitzer, contracted pneumonia and died at the age of two. His other daughter, Lucille Pulitzer, died at the age of 17 from typhoid fever. According to Columbia University Libraries, Lucille's death was a particularly nasty blow to Pulitzer, as she was said to be his favorite child. Pulitzer would go on to establish the Lucille Pulitzer Scholarship at Barnard College in her honor and later dedicated the Columbia School of Journalism to her memory.

After Pulitzer's death of heart failure at the age of 64, his sons would take over as the managers and owners of the New York World (which went under in 1931) and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (which still continues to be published but not by the Pulitzer family anymore).

Peter Pulitzer was married to Lilly (Pulitzer) McKim

Herbert "Peter" Pulitzer was Joseph Pulitzer's grandson. He grew up fabulously wealthy thanks to his grandfather's legacy. Cocky, good-looking, and rich (he had his own business as the owner of a Florida orange grove and cattle), Peter earned himself a reputation as a ladies' man. But surprisingly enough, he fell hard for one Lillian McKim — 21 years old and from an equally wealthy Northeastern family. Peter and Lilly astonished all of their friends and family by suddenly eloping in 1952. According to W Magazine, the two had a fairly eccentric life, throwing huge parties and accumulating a massive menagerie of cats, dogs, monkeys, and a calf. Eventually, Lilly would be remembered best as the famous fashion designer Lilly Pulitzer, creating an entire beach and resort clothing line.

Their marriage, however, wouldn't last. In fact, their 1969 divorce came about as abruptly as the marriage itself had. Lilly had grown restless — and she'd just met Enrique Rousseau, who was working with Peter on building a hotel on the beach. According to Vanity Fair, Enrique and Lilly married quickly after her divorce, and Lilly would forever regard him as the love of her life — the two remained married until Enrique died in 1993.

Peter Pulitzer had a scandalous divorce

After his divorce from Lilly, Peter Pulitzer went on to marry again — this time to Roxanne Dixon, a woman nearly 21 years his junior. Peter and Roxanne Pulitzer's marriage is best remembered for their nasty, highly publicized, tabloid-worthy 1982 divorce that rocked Palm Beach, Florida. According to The Washington Post, Peter Pulitzer tried to avoid the spectacle by offering Roxanne a Porsche, $45,000 per year in child support and alimony, and four years in their house, not to mention a $200,000 home of her own. But Roxanne wanted more and decided to take her fight to court. And that's where the vulgar mudslinging all came out.

Peter accused Roxanne of "gross marital conduct" by allegedly having affairs with a French baker, a handyman, a Grand Prix race car driver, and the wife of another millionaire. (Roxanne and said wife denied this.) Roxanne accused Peter of incest with his daughter. (There was no evidence to support this.) Each spouse accused the other of introducing them to hard drugs.

Ultimately, the judge ruled in Peter's favor and awarded him custody of his and Roxanne's twin boys. Peter's accountant said that thanks to Roxanne's prolific spending habits, Peter's net worth had fallen from $25 million to $2.5 million. The judge ruled that Roxanne would leave the marriage with "a $20,000 Porsche automobile, purchased with the husband's funds, about $60,000 in jewelry, purchased in large measure with the husband's funds, $48,000 in rehabilitative alimony, $7,000 equity in the husband's boat, and $102,000 in attorneys' fees."

Roxanne Pulitzer wrote a tell-all book

There was no love lost between Roxanne Pulitzer and her ex's family. According to The Washington Post, Peter's daughter, Liza Leidy (his daughter with Lilly,) certainly didn't mince words after the divorce proceedings came to an end: "I just hope she feels as terrible as she made all of us feel the past year. It has been a nightmare. She is getting paid back for what she has done. She has been a real wretch about it. I hope she has suffered as much as we have."

Roxanne left her marriage to Peter Pulitzer with little money and struggled to make ends meet. First, she sold all the jewelry she took from her marriage — it was worth $60,000, but she only got one third of its value. Then, she had to borrow money from her mother just to get an apartment and found a job teaching aerobics. But Roxanne's two big paydays came first from doing a spread for Playboy and second from writing her tell-all book with the eyebrow-raising title, The Prize Pulitzer. Roxanne described all the tawdry aspects of her life and marriage to Peter Pulitzer with details of sex, drugs, and wild parties — none of it very flattering to Peter.

To many, a tell-all book might seem to be a crass way to cash in, but it worked for Roxanne. According to the Los Angeles Times, her autobiography landed at number ten on The New York Times' nonfiction bestseller list in 1988.

Peter Pulitzer was saved from bankruptcy — thanks to his ex-wife

They had a nasty, public divorce, but Roxanne Pulitzer managed to save her ex-husband, Peter, from bankruptcy. Roxanne and Peter's twin sons, Mac and Zac, went into business with their father, a vast orange grove owner. But financial problems started in 2006, when 88,000 grapefruit trees had to be destroyed after becoming infected with citrus canker. This led to Peter being unable to make the payment on their $1.3 million mortgage. By this time, Roxanne Pulitzer was married to her fifth husband, Tim Boberg. And it was Zac and Mac Pulitzer who went to Boberg, their stepfather, for help. Roxanne was certainly surprised by her ex-husband's downturn in fortune, as noted by The Palm Beach Daily News: "I never thought Peter would run out of money. The pendulum swings. It's a different ending."

Roxanne's husband ended up guaranteeing the mortgage, agreeing to pay $6,000 in monthly interest and even giving a $400,000 credit line to keep Pulitzer Groves going. From the outside, Peter Pulitzer being bailed out by his ex-wife was a moment of vindication for Roxanne Pulitzer, who had endured being vilified and ostracized in Palm Beach society.

Zac and Mac were ecstatically grateful for Boberg's help. Peter was likewise very appreciative of Boberg's assistance, but distinctly more muted on the topic, telling Forbes, "I want to thank Tim for any help he has given. But this is not a subject that I want to talk about."

The Pulitzers went to court — against each other

In 1986, the Pulitzer media family became bitterly divided regarding control of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and other media properties. Some family members wanted to sell the Dispatch and maximize their wealth, while others wanted to hold onto the properties and continue to pass them down to the next generation. When the family failed to come to an agreement on their own, they ended up in court — against each other. In a statement to The Washington Post, one Pulitzer family member, David Moore, who wanted to keep the newspaper in the family, expressed his regrets that the feud had turned into a court battle: "It is a very sad thing. This is not a happy time, I don't think, for any of us. There are not winners in a situation like this."

The family eventually reached a settlement and retained control of the Dispatch. It wouldn't be until 2005 that Pulitzer, Inc. would be sold (including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch) to Lee Enterprises.

The Pulitzers were caught in another media family's feud

The Pulitzers were able to end their public family court dispute, but in 1997, they found themselves in the middle of another media family's feud. According to the St. Louis Business Journal, Pulitzer, Inc. had just purchased another old family media company, Scripps League Newspapers, from Betty Knight Scripps. However, the sale of the family company did not sit well with 51-year-old Barry, the son of Scripps family patriarch Edward W. Scripps. Barry accused his mother, Betty, of taking advantage of his father's poor health and selling Scripps League Newspapers to the Pulitzers — depriving him of his inheritance.

Apparently, in 1976, Edward Scripps had given his wife half of his voting shares of stock, giving her significant power in the company. But in 1995, Edward's health began to fail, and Barry believed that Betty decided to seize control and use her voting right to sell off the company. Barry claimed that he was supposed to run Scripps League Newspapers once his father officially stepped down, but he was fired from the company shortly before its sale to the Pulitzers. Barry ended up suing his own mother. According to New York Magazine, Barry's lawsuit against Betty was ultimately tossed out.

Joseph Pulitzer IV died at 65

Known as "Jay" to everyone, Joseph Pulitzer IV died of a heart attack at age 65 in 2015. It was a shock to his family and all who knew him. As noted by The Washington Post, Jay was the great-grandchild of the first Joseph Pulitzer and the only child of Joseph Pulitzer Jr. (who is technically the third Joseph Pulitzer), owner of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. All his life, he was primed to take over the family media company one day. But this didn't end up being the case. Jay was certainly dedicated to the newspaper business, starting out as a reporter at the Dispatch, working his way up to correspondent, taking over as night city editor, and finally earning the corporate vice president position.

Unfortunately, Jay never did rise to take his place as the next reigning Joseph Pulitzer. After his father passed away in 1993, Jay's uncle, Michael Pulitzer, took over as head of the company, and majority control of the stock went to Jay's stepmother, Emily Pulitzer. Only two years later, Jay was forced out of the family business by the company's controlling family members. And it was in 2005 that the Pulitzers sold off their company to Lee Enterprises. Jay Pulitzer spent his retirement years in Big Horn, Wyoming.