These Are The Penguins That Don't Live In The Cold

Some animals are awe-inspiring, some make us want to cuddle them endlessly, and some are just inherently funny. Penguins are definitely the latter — they're flightless little birds who look like they're permanently dressed up for a night on the town, even though they're most famous for living in one of the most inhospitable places on the planet.

Antarctica isn't just cold, it's the kind of cold that makes your insides freeze as fast as your outsides. Aurora Expeditions says the average temperature across the continent — which is also one of the driest and windiest places on the planet — is a terrifying -70 degrees Fahrenheit. In the winter months, it gets down to -130 degrees Fahrenheit, and the summer maxes out at a not-so-balmy 46 degrees Fahrenheit.

But penguins seem totally cool with it, no pun intended. The temperature is just part of the conditions they thrive in, and Oceanwide Expeditions adds that during the Emperor penguin's breeding months, they're also fighting 124-mph winds.

That's the most common image of penguins, right? But here's the thing — there's only a few species of penguins that are adapted to live in those kinds of extremes. Others have opted for a different life, and seemingly contrary to what penguins are, desert penguins are definitely a thing. So are forest penguins! They're just as adorable, too, so let's talk about the penguins that decided to give snow and ice a miss.

The sad story of the world's only tropical penguin

They're called the Galapagos penguins, and they live on a few of the islands that make up the Galapagos Islands (which, notes the IGTOA, are situated in the Pacific Ocean about 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador). It's an insanely cool place, where penguins can hang out alongside flamingos. Neat, right?

IGTOA says the aptly named Galapagos penguins are one of the smallest penguins in the world, standing about 14 inches tall, and hunt during the day, when they show off their mad swimming skills by darting and diving through the water at up to 25 mph.

According to National Geographic, they have personalities that match their adorable, tiny size — they're known for being pretty mellow when it comes to things like scientists, and that's been a good thing, because those scientists are trying to determine how fast their populations are shrinking.

And they are shrinking. Climate change has been so drastic that it's shifted the populations of crustaceans and fish that the Galapagos penguins thrive on, which means they've got to travel farther and farther from home to find a decent meal. That's made these tiny penguins incredibly vulnerable to predators, and in 2017, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) officially classified them as endangered. Protections have been put in place, but only time will tell if tropical penguins will be a thing of the future.

These forest penguins have a daily bathtime ritual

The Snares islands are pretty unique even as islands go. According to New Zealand's Department of Conservation, these sub-Antarctic islands were never settled by humans or had non-native species introduced, which makes them a paradise on earth for species like the Snares penguins.

When the BBC went to visit these gorgeous little forest penguins, they found something they described as "a labyrinthine penguin city." Each individual colony had their own separate area, but they were connected by a series of well-worn paths that had been traversed by countless pairs of penguin feet. Paths wound their way up into the forests from the ocean, to and fro beneath the forest canopies, and if there's anything in this world to make the most cynical minds believe in magic, it's a penguin city.

BBC Earth says there's somewhere around 60,000 penguins living on Snares, and they're thriving thanks to a complete lack of predators. They do face one danger, though — the mud. When their waterproof feathers get muddy, their natural insulation doesn't work nearly as well. The answer? Daily bath times, when they head off down some of their many paths toward communal bathing pools, where they get themselves all sparkling clean and re-oil their feathers in a three-hour ritual.

The nice little penguin with the naughty name

The Aquarium of the Pacific says they're officially called the African penguin, but they're more commonly called Jackass penguins. Why? When they squawk, they sound more like a donkey than a bird.

These penguins live off the southwestern coast of Africa, where they nest in flat, sandy, and rocky islands and along the mainland coast. They stick mostly to areas where the average water temperature is between 41 degrees and 68 degrees, which means most people wouldn't want to swim alongside them, but it wouldn't be entirely unbearable.

Their relatively warm-water habitat isn't even the coolest thing about them — that's reserved for findings that suggest their donkey-like language has a lot in common with our own. In 2020, LiveScience reported on a study in the journal Biology Letters that found that not only do the penguins bray in "syllables," but their speech patterns and the frequency that they use long and short "words" follows the same rules as human language — specifically, Zipf's law of brevity, which says that the more often a word needs to be used (like "the"), the shorter it is.

The penguins were also found to use "words" that follow the Menzerath-Altmann law, which basically says long words have short syllables, and short words have comparatively long syllables. So far, they're the only non-primate animals found to be capable of speech that follows some of the same patterns as human-speak.

The penguin with a built-in cooling system

Humboldt penguins haven't just settled somewhere there's no snow, ice, and below-freezing temperatures, they live somewhere that it gets so hot, they need a built-in cooling system to survive.

The St. Louis Zoo says that Humboldt penguins are easily recognizable by the bare patches of pink skin they sport on their faces, feet, and beneath their wings — areas that can get even more red. During the hottest times of the year, the Humboldt's climate of choice can get all the way up to 108 degrees, which is when blood flows into their faces and extremities to allow them to get rid of body heat... and blush. Cute, right?

So, where do they live that it gets so hot? Along the west coast of South America, all the way up to the equator. According to Oceana, they tend to stay along the route of a current of cold water that rushes up from Antarctica.

Unfortunately, these unique birds share a common story with countless other species — they're endangered. Climate change has vastly reduced their food supply, and they're also facing habitat destruction. Humboldt penguins build their nests in the droppings of other sea birds, and this is the same guano that's regularly stripped and sold around the world as fertilizer. No guano, no eggs, no babies, and no cute little blushing penguins.

The penguins that winter in Rio

Take a visit to the Aquarium of the Pacific, and you'll get to see their Magellanic penguins. Some of these big birds — which reach a height of about 30 inches and weigh up to 14 pounds — were bred in captivity, while others were rescued from the beaches of Brazil. After their rehabilitation, wildlife experts decided they were incapable of surviving on their own in the wild — and for these penguins, it's not just a matter of hanging out on the beach and swimming for their food. They're migratory.

From September to April, they spend their breeding seasons on the islands off the coasts of Chile and Argentina. For this part of the year, they're total beach bums, preferring to hang out and nest on sandy beaches (or, sometimes on rocky scrubland). When winter comes, though, they head to the coasts of Peru and Brazil, when they spend most of their time in the water. It's no quick swim, either, as National Geographic says that some birds cover 4,000 miles in their migratory pattern.

There's bad news for these guys, too. They're officially considered Near Threatened (NT) by the IUCN, for a few reasons. Climate change and a threatened food supply are coupled with devastation from oil spills and ongoing oil pollution. In order to combat the population loss, UNESCO established a massive reserve along Argentina.

Teeny-tiny penguins that are as graceful on land as they are in water

Part of what makes a penguin so funny is watching them walking on land. Sure, they make up for it when they're in the water, but their goofy little waddles are just precious. The southern rockhopper penguin is a little different, though. These tiny penguins — which weigh just a few pounds each — hop instead of waddle. According to Oceana, they don't have the same awkwardness most penguins have on land, and that's probably a good thing as they live on the rocky coastlines of islands north of the Antarctic.

National Geographic says these little birds have something of a Napoleon complex, and they're pretty aggressive toward anything — regardless of size — that they feel has come too close. They've earned their street cred, too, as they're tough enough to take on squid as part of their regular diet.

Year after year, males will head back to the same breeding ground, where they attract a mate — usually the same female — with a wiggle of their stupendous yellow eyebrows. Unfortunately, when it comes time for pairs to meet again for breeding season, more and more penguins are disappointed — Southern rockhopper populations have declined by as much as 90% in some areas, making for some sad, lonely penguins, indeed.

The penguins who are total jerks

This NZ life calls the eastern rockhopper penguin the "punk-rocker penguin," and that's legit. They definitely have the hair down, and they — like the other rockhopper penguins — have a hopping gait that makes them look even more punk as they bob and weave their way across the rocky shorelines of New Zealand.

These little penguins have a few things going for them. They're great parents, with males and females working together and taking turns incubating their eggs, then the male stays with the chicks on guard duty while the female hunts and brings back food. They're often seen grooming each other, and that's adorable. But they're also jerks to anyone outside their species or outside their family group and will definitely throw down when it comes time to pick the nicest rocks for their nesting areas.

It's also worth noting a few things — there's no agreement on whether or not the "rockhopper" family of penguins actually belong to separate species or if they're subspecies, and New Zealand's rockhopper numbers are in swift decline. The Endangered Species Foundation says climate change is impacting their feisty little penguins in awful ways. Take Campbell Island. They had 800,000 breeding pairs in 1942, and now, that number hovers around 51,500.

Who says bushy eyebrows are a fashion no-no?

The American Bird Conservancy says that in spite of sharing a name — and eyebrow style — with the southern rockhopper penguin, the northern rockhopper (or Moseley's) penguin is considered a separate species. As their name suggests, they're found a little farther to the north, and even though they have some of the same fat and feather adaptations that colder-weather penguins have, the Australian Antarctic Program says they're usually found in the temperate waters of the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean.

These temperamental little birds are described as "pugnacious," which basically means they'll throw down in a pushing-and-shoving match pretty much anywhere, any time, and over anything. But, at the same time, they're highly social, and once their chicks are a few weeks old, parents will get together and put them all into a sort of penguin day-care, where adults will take turns watching the group of chicks while others go out to hunt (as several other penguin species do, as well), in what might be the only reality TV show the world really needs.

It turns out that fairies are real after all

The world can be a violent, mean, miserable place filled with all kinds of news that's enough to make any sane person just want to go hibernate until mankind gets their act together. And while it's impossible to fix all that, here's something that makes it just a little bit better — fairy penguins are a thing.

They're also called Little penguins, and they're unspeakably adorable. Weighing an average of just 2 pounds and reaching towering heights of just about 13 inches, the Penguin Foundation says they're still considered a top-tier predator... which is a little tough to wrap your head around, as they waddle past seagulls that tower over them. As if the sheer determination on those tiny faces isn't cute enough, there's also the fact that they've ditched the typical black-and-white penguin uniform, and instead, they come in varying shades of blue and white.

The Aquarium of the Pacific says these penguins stay in the temperate waters around Australia and New Zealand, and they tend to be incredibly shy but very vocal during breeding season. (Also, the noise that chicks make is described as "a high-pitched beep," because of course it is!) It's believed that fairy penguins are the penguins species that's closest to their ancient ancestors, which just exponentially increased the potential cuteness factor of the next Jurassic Park.

The rarest penguin of them all

New Zealand's $5 bill has a penguin on it, but it's not just any old penguin. It's the yellow-eyed penguin, also known by the Maori name "hoiho."

New Zealand Geographic says these little penguins are incredibly shy, and after spending their days looking for food in the seas — and swimming as far as 15 miles to find it — they retire to private nesting areas they build away from even other penguins of their own species.

And that's the problem. Not only are they incredibly shy, but they're incredibly cute. That's led to an enormous number of tourists who think getting a selfie with one of the birds is a high point of the New Zealand vacation, especially considering the birds seem to freeze in place when they're approached. But they're not waiting for their big social media break — they're terrified. Add in fishing that's getting increasingly more difficult, their numbers are dwindling in spite of conservation efforts. The Yellow-Eyed Penguin Trust says there's only a few hundred breeding pairs left in the wild, where they continue to be threatened by human activity, overfishing, and climate change.

Wait, penguins with white flippers?

They're called White-flippered penguins, and it's a bit of a misnomer — their flippers aren't completely white, but they're edged with white. They're also tiny and look enough like Fairy Penguins that, according to the Penguin Trust, they were once thought to be the same species until DNA testing proved otherwise.

These little cuties — along with numerous other penguin species — are considered threatened. They're officially designated as "endangered" by the IUCN, and here's the thing — they have an incredibly small range, living and breeding only on Motunau Island and the Banks Peninsula in Canterbury, New Zealand. At one time — before Europeans settled in the area — the coastlines were home to tens of thousands of pairs. Now, though, interference from humans (particularly the fishing and oil industries) have caused numbers to plummet. They're considered the only indigenous creature in the area, and there's only about 4,000 pairs left.

Why are there no penguins in the northern hemisphere?

So, here's a question — since it turns out that there's penguins that live as far north as the equator, why have none made it any farther north?

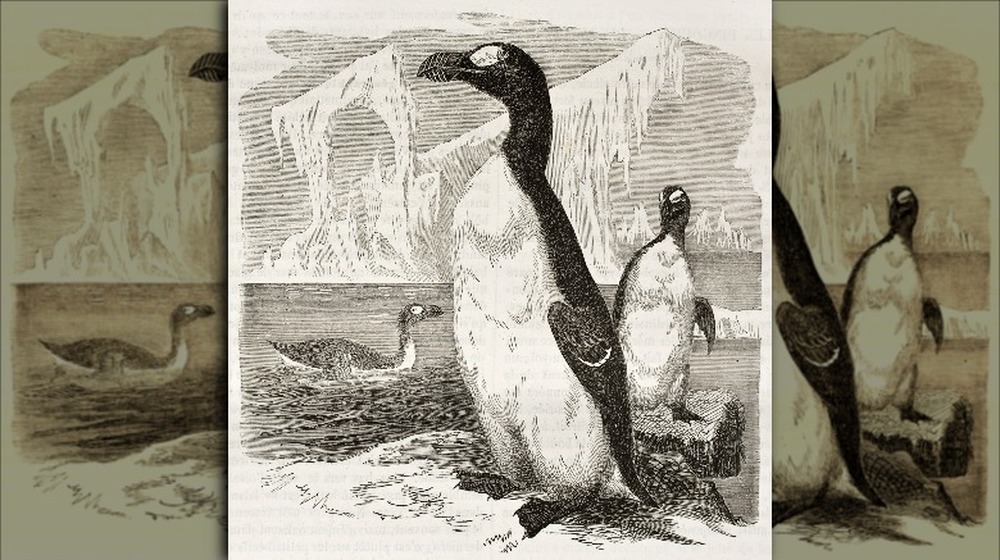

According to Swansea University's Jessica Emma Thomas (via The Conversation), the northern hemisphere did, in fact, have its own version of a penguin until not that long ago. The great auk wasn't technically a penguin, but at the same time, it was called "the original penguin," just to make things a little more confusing. These massive, flightless, black-and-white birds once ranged from the east coast of Florida, up into and around Greenland, and all the way to the Scandinavian and Italian coasts.

They were once so plentiful that they were a reliable food source for years, but Thomas and her team of researchers found that things changed around the year 1500. That's when European explorers discovered then-rich fishing grounds of the northern Atlantic and started killing a lot more birds. Over the course of just 350 years, the species was hunted to complete extinction, with the last great auks disappearing (or being killed and stuffed for museum display) in 1844.

Prehistoric penguins?

Sometimes, scientists make discoveries that make everyone take a step back and say, "Wait, what's this, now?" That happened in 2007, when The Guardian reported on a massive, prehistoric penguin that had been discovered in Peru.

The fossils belonged to a penguin that had lived about 36 million years ago, and that's not the weirdest thing about it. Scientists say that it looked pretty much like one of today's penguins, with a thick neck and flippers meant for swimming... but it was roughly 5 feet tall, and the 7-inch long beak it sported could do some serious damage. It was so weird, in fact, that researchers started to suspect it used that beak like a spear.

The prehistoric penguin was formally named Icadyptes salasi, and the sheer size of the beast wasn't entirely surprising. At the time, the Earth — and particularly that area of Peru — was incredibly warm, which would have increased the amount of potential prey the gigantic penguins would have had to feast on.

Not scary enough? The prehistoric remains of another, less tropical penguin have been found in New Zealand. Nordenskjoeld's giant penguin lived about 6 million years ago, stood about 6-and-a half-feet tall, and weighed around 200 pounds.