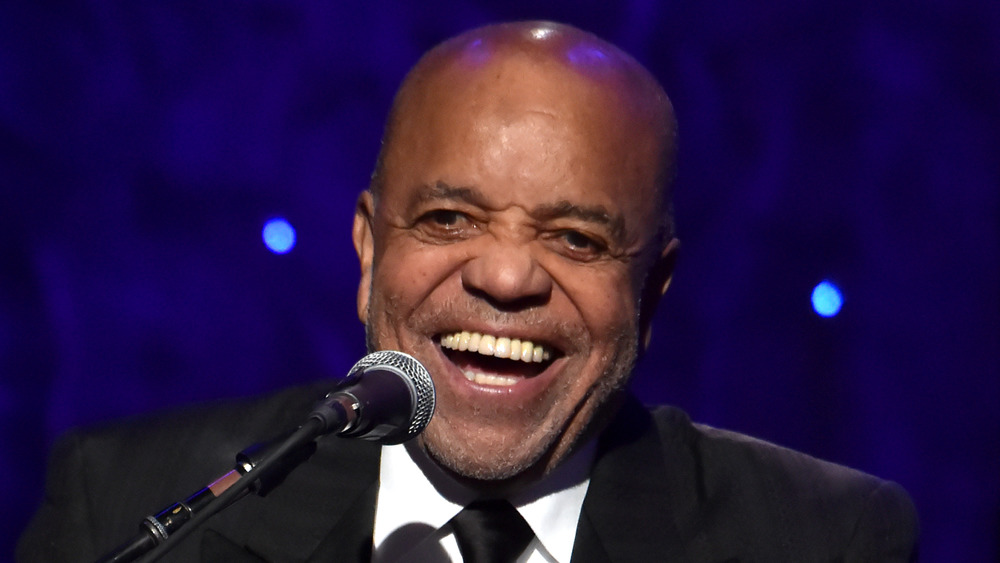

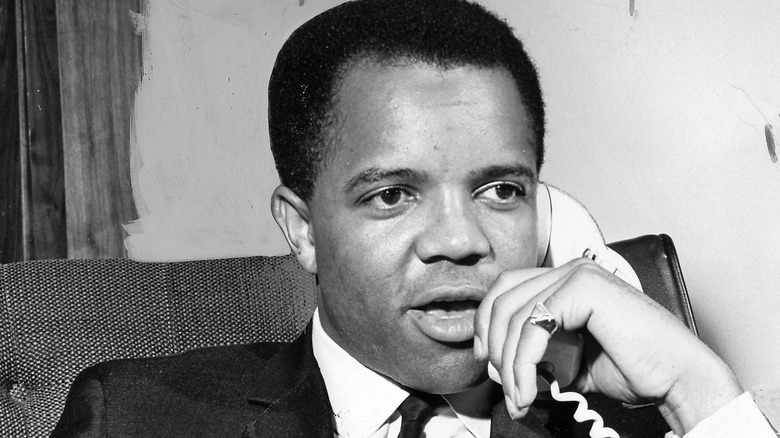

The Untold Truth Of Motown Founder Berry Gordy Jr.

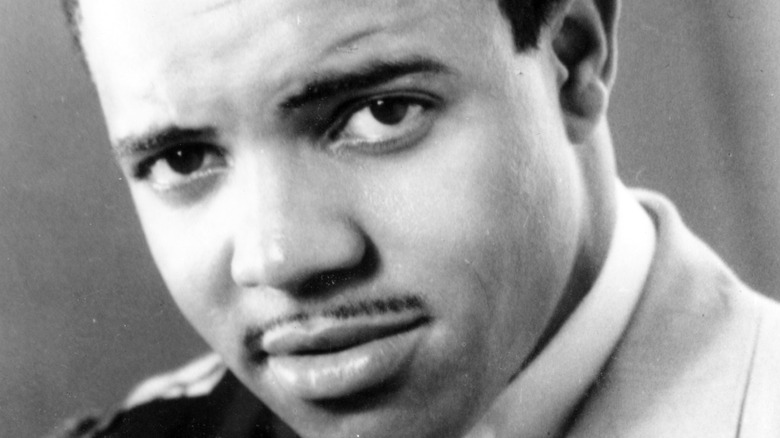

Today, the word "Motown" is so ingrained in our culture, it's easy to forget it hasn't always been a way to casually refer to Detroit or to describe a kind of infectious pop-soul music. In fact, Motown Records as we know it has only been around since 1960, but its influence is mighty. Much of that is thanks to Berry Gordy Jr., Motown's founder. Gordy was born in the Motor City in 1929 and his beginnings are a classic Great Migration experience.

Born the seventh of eight children, Gordy's father moved the family from Georgia to Detroit before Gordy was born, likely drawn there by jobs in the booming auto industry. Gordy dropped out of high school to pursue his dream of becoming a professional boxer, and he had a pretty good record, too, as BoxRec reveals, but the Korean War draft interrupted that dream. After a return from Korea (where he'd earned his GED), he married and found work at the Lincoln-Mercury plant. For a while, it looked like Gordy would follow the traditional Detroit path. But he was about to meet a young singer named Jackie Wilson, a meeting that would change the course of both men's lives.

His first foray into the music business was in the wrong genre

Berry Gordy Jr.'s first foray into the music business came in 1953, the year he returned from service in the Korean War. Newly married and in need of work, he decided to set up a record store, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to inherit the family plastering business. Gordy's shop was named the 3D Record Mart, because, as he writes in his memoir "To Be Loved," "three-dimension was the technology of the time."

Unfortunately for Gordy, he and his Detroit clientele were out of sync when it came to musical tastes. "I was heavily into jazz," he told the BBC's Desert Island Discs program, so that was the type of music that the 3D Record Mart kept in stock. The subtitle of the store was even "House of Jazz," a name Gordy attributed to a business partner in his memoir "To Be Loved." "In Detroit," he said on Desert Island Discs, "the people that came in there were asking for the blues." Gordy's attitude — that his customers needed musical education — didn't help. The store soon folded, and Gordy turned to other jobs, including selling cookware and the Lincoln-Mercury automotive plant. He had a few years to go yet before becoming a hitmaker.

Motown is born

Writing for and recording songs with Jackie Wilson gave Barry Gordy the foothold he'd needed in the music industry. Biography tells us that some of their initial collaborations, like "Reet Petite" and "Lonely Teardrops," still score radio airtime. Spurred on by their success, but still wanting more, Gordy accepted an $800 loan from his family and, in 1959, began a new venture, Motown (a combination of "Motortown," one of Detroit's nicknames). Here, he hoped to take the most efficient parts of the auto industry and apply them to musical talent.

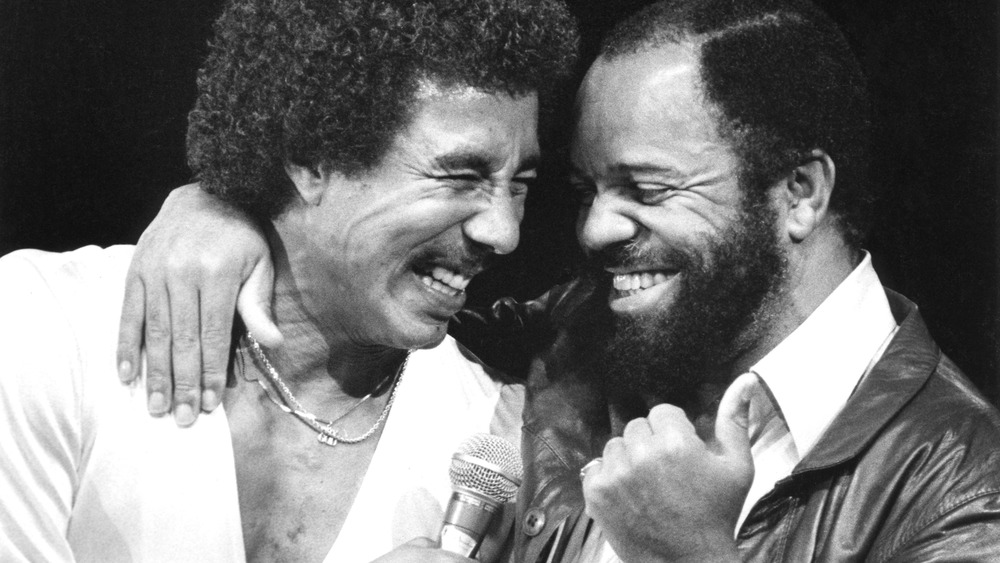

According to the Motown Museum, Gordy believed his process could transform a random kid off the corner and turn him into "a polished performer." Over the next eight years, Motown would rule the charts thanks to Gordy's skills at writing and producing, combined with an eye for talent. Superstars from Motown's heyday include Wilson, but also The Four Tops, The Supremes, The Isley Brothers, Smokey Robinson, The Temptations, Aretha Franklin, and more.

But for all the talent, the meteoric rise of Motown could not go on forever. In 1968, Motown lost one of its most lucrative assets, the songwriting team known as Holland-Dozier-Holland. As Zani explains, years of fighting over profit-sharing and royalties cost Gordy the powerhouse trio behind dozens of the label's most-infectious hits. It's not that Motown was dead — it would go on to see the rise of the Jackson 5 and the release of Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On" – but it was struggling.

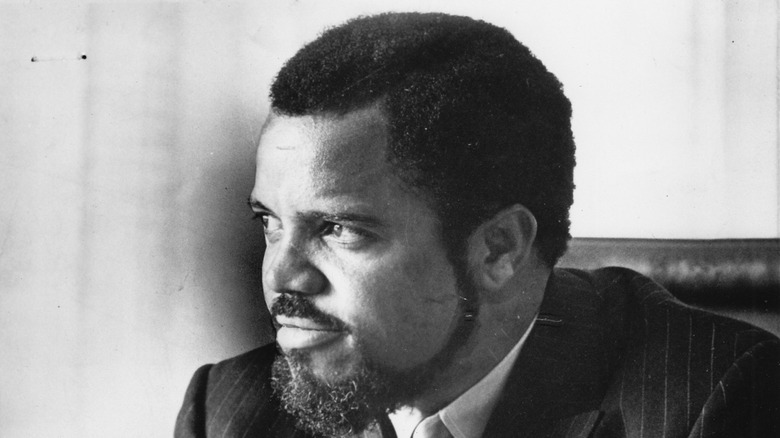

His relationship with Diana Ross contributed to tensions on Lady Sings the Blues

Berry Gordy Jr.'s relationship with singer Diana Ross has been a long and changeable one. Ross' first job for Gordy was as his secretary, a job she failed miserably at. But as lead singer of the Supremes, she went on to captivate America and her boss. He embraced and promoted her as a star performer, to the point where he was charged with prioritizing her over other members of the group. Ross put complete faith in Gordy to manage her career. Eventually, the two became lovers. And in the 1970s, they headed for Hollywood and "Lady Sings the Blues."

In his memoir "To Be Loved," Gordy wrote that it was his idea to star Ross in the Billie Holiday biopic in 1971, despite studio objections. Ross' biographer contended that Gordy was the one who first turned down an offer from the film's producer and director, who convinced him that she could handle the part despite no prior acting experience (per The Hollywood Reporter). Either way, once production began, their relationship complicated filming.

While Gordy and Ross' sexual relationship was over by that point, there was still strong affection between them, and Gordy became jealous while watching love scenes between Ross and Billy Dee Williams. According to Williams (via "Diana Ross: An Unauthorized Biography," by J. Randy Taraborrelli), Gordy interrupted rehearsals of their big kiss, frustrating both actors. His cover story was that he wanted to save the moment for film — which he did eventually allow to roll.

He got Billy Dee Williams his start (and was later played by him)

In his memoir "To Be Loved," Berry Gordy Jr. claims that Billy Dee Williams came into his audition for "Lady Sings the Blues" with an attitude and gave two terrible screen tests. "But something had gotten to me," wrote Gordy. "Both times, regardless of his poor readings, I could see the interplay between Diana [Ross] and him and I liked it." He made up his mind that Williams was right for the part of Louis McKay and assured the actor that he would champion him. Producer Jay Weston has claimed Williams was his choice, as per The Hollywood Reporter. Whoever first took a liking to Williams, the two producers and director Sidney J Furie all agreed that they wanted him as McKay and got him the part.

Williams and Gordy maintained a connection after "Lady Sings the Blues." The actor appeared in three more films made by Gordy's production company. He also played Gordy himself in the miniseries "The Jacksons: An American Dream." When Gordy was given an Icon Award at the Critics Choice Association's Celebration of Black Cinema & Television in 2022, Williams was the presenter. "You are so deep in my soul," Williams told him (via Urban Hollywood 411). "I don't mean to be corny over here, but [working with you] was the experience of a lifetime."

Berry Gordy has gone into horseracing

It's been said that Berry Gordy Jr. became distracted by endeavors away from Motown in the 1970s. The label was losing money and artists, and Hollywood beckoned with opportunities to make Diana Ross a star. But Gordy dabbled in other pursuits over the years. In 1980, he dipped his toe into the world of horse racing. According to UPI, he put down $1 million on a horse named Argument and saw it win in its first race under his ownership (in partnership with Bruce McNall), the Washington D.C. International. "I don't know why everyone is concerned about winning these races," Gordy joked afterward. "Is this supposed to be hard?"

Gordy's involvement in horse racing was intermittent throughout the '80s and 1990s, but he maintained enough interest to establish Vistas Stable for his horses. Several of his animals were originally from Britain or Europe and were brought over to successfully compete in American races. Gordy's horses were under the care of trainer Rodney Rash for a brief time in the '90s; Rash's death in 1996 cooled Gordy's enthusiasm for the sport (per Blood Horse). But McNall helped pull him back in during the early 2000s.

He adapted his own memoir into a musical

In 1994, Berry Gordy Jr. told his life story as he saw it. "To Be Loved: The Music, The Magic, The Memories of Motown: An Autobiography," detailed Gordy's upbringing, the birth and development of Motown, and the ups and downs of Gordy's love life — and served as a platform for him to challenge certain claims about his career. Pages were spent refuting Motown's alleged links to the Mafia and accusations that Gordy had ripped off the artists working for him. He also weighed in with his thoughts about the decline of Motown and his eventual sale of the company.

It was allegedly continued misperceptions about the latter issue that motivated Gordy to adapt his memoir into a musical. "Motown: The Musical" is a jukebox musical, using a collection of Motown hits to tell the story of the company's rise within the frame of a flashback during Motown's 25th anniversary in 1983. Gordy wrote the book for the show, which hit Broadway in 2013 and traveled to Britain's West End in 2016. Gordy went with it at first, describing the songs of Motown as a record of his life in a promotional interview with The Telegraph. The paper noted different ways he fudged the chronology.

Other papers noted perceived weak points in the show itself. In a representative review, The New York Times praised the music but faulted Gordy's book. The paper felt while there was so much music, the story was crowded out.

A road manager accused him of plenty of shady activity

Producers are rarely universally beloved, and Berry Gordy Jr. has faced criticism over the years for his business practices. But one man in his orbit went further than most in airing grievances. Released in 1992, "Deliver Us From Temptation: The Tragic and Shocking Story of the Temptations and Motown" was written by Tony Turner, with help from Barbara Aria. Turner, a Motown devotee, was also road manager to three of the Temptations, or so he claimed. His book was loaded with allegations and innuendo about various figures connected to Motown, including some salacious charges against its founder.

Gordy, Turner wrote, had once been a pimp on the streets of Detroit, and a rather inept one at that. His management of Motown was compared to prostitution, with the artists portrayed as short-sighted street workers taken advantage of. Elsewhere, he claimed that Eddie Kendrick of the Temptations repeatedly asked him if he'd had an affair with Gordy; it was allegedly a widespread rumor among Motown artists, curious why Turner was held in such high regard with the company.

Turner didn't refute the allegation in his book. Later on, he explicitly claimed in the pages of the New York Daily News (via The Buffalo News) that Gordy had seduced him as a teenager and coerced Motown singers to have abortions. The claims were enough for Gordy to sue, arguing that he and Turner never met.

Berry Gordy's ex-wife claimed he cheated her out of her share in Motown

Berry Gordy Jr. has been married three times, all of them ending in divorce. His second wife was Raynoma Singleton, whom he first met in 1958. They were married in 1960 and divorced four years later. Gordy has maintained that he and Singleton renewed friendly relations after the divorce for the rest of her life. But Singleton told a more complicated and bitter story in her memoir "Berry, Me, and Motown: The Untold Story," co-written with Bryan Brown and Mim Eichler.

In "The Untold Story," Singleton alleged that she had been swindled out of her due riches and credit for Motown's success. The seed of Motown, she claimed, was a music writing company named Rayber that she devised. Her songwriting duties included arranging, back-up singing, and prep work for the business end of things. Once Motown was up and running, Singleton picked up the nicknames Miss Ray and Mother Motown for her role in the company. But her name, at Gordy's insistence, wasn't on any of the paperwork.

Infidelity hurt their marriage, but the final straw came when Singleton sold bootleg copies of Motown records to keep its New York office afloat. That got her arrested, and Gordy refused to drop the charges unless she pulled out of the company and agreed to a meager divorce settlement. For his part, Gordy never commented on the memoir; a representative called it "trashy and false" (per People).

Motown and the Mafia

Almost since its inception, Motown has been dogged by rumors that it was connected in some way to the American Mafia. It's not a charge unique to Motown; many record companies, from small labels to the so-called big six producers, were accused of having mob ties, at least at their fringes. But it's a claim that Berry Gordy Jr. has been particularly sensitive to over the years.

In an interview with David Sheff, Gordy flatly denied any connection to the Mafia. "That rumor grew from an article that appeared in a small neighborhood news sheet," he said. "It said, based on nothing, that Motown was being taken over by the Mafia. When it came out, we laughed at it. But the item was picked up by larger papers." The rumors gained enough traction that the FBI's organized crime division felt compelled to investigate and even called Gordy in for an interview. He maintained his innocence, and the agents at the Detroit office conceded that there was no evidence of any link between Motown and the mob.

In talking to Sheff, Gordy suggested that the rumors might also have been fueled by the fact that the head of Motown's sales department, Barney Ales, was Italian. In fact, Ales was Sicilian-American, and he seemed to enjoy being coy about any Mafia connections when he spoke to the press. He never explicitly denied such a link to The Detroit News, for example, and he was at ease with descriptions of himself as Gordy's hatchet man.

Conflicts of interest

The management style of Motown has been described as paternalistic. Besides producing and distributing records, the company kept a tight control over artists' images, finances, and even personal lives. Berry Gordy Jr. himself was willing to acknowledge the extent of control he desired in an interview with David Sheff, and he detailed the many services he and Motown provided. "I worked with other aspects of their lives, because raw talent wasn't enough," he said. "We had a charm school, chaperones. We made sure the artists paid their taxes." There was also life and career advice offered in a family atmosphere.

But there was a problem with this arrangement. Having the company responsible for recording the records also act as the management of the musical acts amounted to a conflict of interest, something Otis Williams of the Temptations admitted to the Chicago Tribune. Gordy has insisted that any such conflict was in the artists' favor. But the situation led to tensions between Gordy and some of his talent, tensions that grew as the share of money earned increased. Gordy has been particularly sensitive to claims that he cheated performers out of earned payments, pointing to the long tenure of certain artists with Motown and the standard practices within the record industry he looked to when starting out. "You don't stay in business for 35 years by not paying people," he told Sheff.

Berry Gordy Jr.'s lasting legacy

Barry Gordy sold Motown to MCA records in 1988, where it continued to move, due to numerous acquisitions and sales – it's now owned by Universal Music Group. The Los Angeles Times reports that the company's price was $61 million. Gordy officially retired in 2019 at the age of 89, a move he told the Los Angeles Times that he'd "dreamed about it, talked about it, threatened it" for a long time.

He's earned the rest. In addition to forever changing the face of American popular music, he's nabbed a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, a lifetime achievement award from the American Music Awards, and the National Medal of Arts in 2016. Not bad for a guy who told Billboard in 2017, "When I started out, all I wanted to do was write some songs, make some money and get some girls — not necessarily in that order."

Berry Gordy Jr. is related to Jimmy Carter

The man known professionally as Berry Gordy Jr. is actually the third member of his family to bear that name. His father went by Berry Gordy Sr., though he gained the nickname Pops Gordy among the artists under contract to his son. The elder Gordy used the nickname for his memoir, "Movin' Up: Pop Gordy Tells His Story." But Pops Gordy was the son of Berry Gordy I. This Berry Gordy was born a slave to mother Esther Johnson on a Georgia plantation. His father was the plantation owner, James T. Gordy, who went on to act as a wagon master for the Confederate Army during the Civil War, Jimmy Carter writes in "A Remarkable Mother."

While one can reasonably doubt that James T. Gordy had much to do with his illegitimate son by an enslaved woman, he had other progeny, as an investigation by historian Lewis Smith found (via WRDW/WAGT). His recognized son, James J. Gordy, went on to have a daughter, Lillian. Her son is former president Jimmy Carter, making him and Berry Gordy Jr. second cousins by way of their shared great-grandfather.