These Were The Biggest Flops In Broadway History

Before movies and television came along, the premiere and most notable place for entertainment in America was the Great White Way — the theaters of Broadway in New York City. Enduring for decades as the absolute pinnacle of drama in the United States, Broadway has been the goal and jumping off point for countless classic and important musicals and plays. Whether you love the all-singing, all-dancing, glitzy spectacle of musicals or can't wrap your heads around them because they're too artificial and performative, you can't deny that productions like South Pacific, West Side Story, Cats, The Book of Mormon, and Hamilton have been an extremely influential part of the arts and culture.

Broadway is also its own little world, a niche in society and the entertainment industry that often operates perhaps too independently of the rest of the country. The result — theater producers spend tens of millions on shows they think will lure New York theater aficionados and eager tourists into paying $100 a ticket for the privilege of seeing what they've done. And so, just like the movies and television, Broadway has housed some massive, ridiculous, money-hemorrhaging flops.

High Fidelity went low

Nick Hornby is among the most acclaimed authors of recent years, and his most famous work is High Fidelity, a 1995 novel about Rob, a self-absorbed record store owner with an encyclopedic knowledge of music obsessed with making lists who surveys his past relationships to find out why his most recent one fell apart. The character and situation are so relatable that High Fidelity has proven highly adaptable, turned into the 2000 John Cusack movie of the same name, a gender-flipped Hulu original series starring Zoe Kravitz in 2020, and, in 2006, a Broadway musical.

The production had an impressive pedigree — Pulitzer Prize winner David Lindsay-Abaire wrote the script, and theatrical veteran Amanda Green penned the lyrics. Hornsby's book was set in London and the Cusack movie in Chicago, so the musical changed the locale again — to New York. It kept the characterization of Rob intact as that of a fussy music snob who prefers punk and indie rock and classic soul.

Perhaps part of the reason why High Fidelity didn't work as a Broadway musical is because the novel was about and for people who don't like commercial, mainstream music... like Broadway show tunes. "If I close my eyes and concentrate really hard, I just might be able to describe a show that erases itself from your memory even as you watch it," Ben Brantley wrote in his savage New York Times review of High Fidelity, which closed after 14 performances.

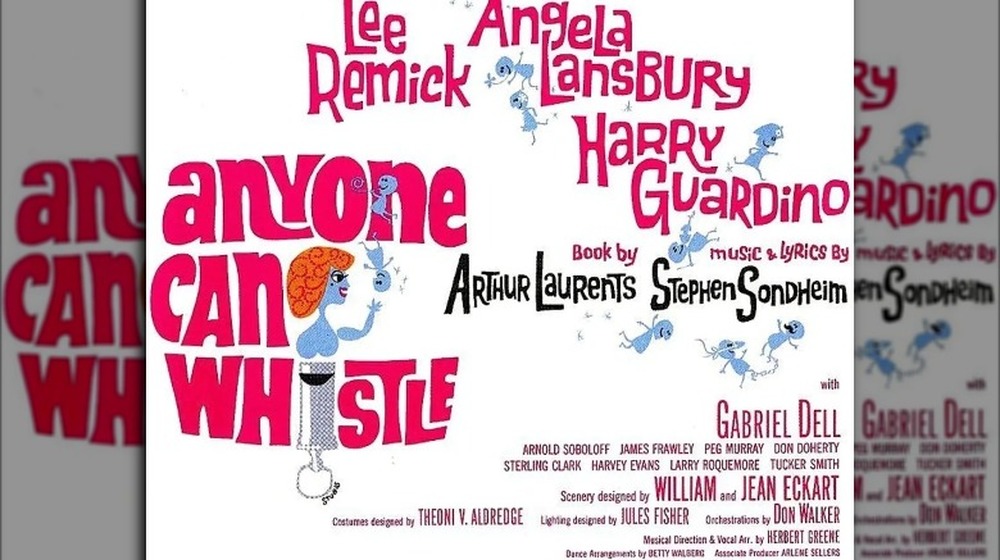

Anyone Can Whistle, but not everyone will like it

Stephen Sondheim is a titan of musical theater, a singular talent who elevated the genre to high art with his complex music and intricate lyrics. Among the Broadway classics in which Sondheim has had a hand – Into the Woods, West Side Story, and Sweeney Todd. The man has nine Tony Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and 15 Drama Desk Awards, so "critical and commercial flop" are not words generally spoken in the same breath as "Stephen Sondheim," but even he had a dud.

In 1964, he teamed up with West Side Story collaborator Arthur Laurents for Anyone Can Whistle. "Arthur and I had written the piece as if we were the two smartest kids in the class (in the back row, of course), wittily making fun of the teacher as well as our fellow students, demonstrating how far ahead of the established wisdom we were," Sondheim wrote in Finishing the Hat (via Everything Sondheim). That smug sensibility apparently shone through in the finished product, a cynical and nastily satirical show about a corrupt mayor who stages a miracle to attract tourists (and money) to her bankrupt, Depression-era town. There's also a romance between a doctor and a nurse, takedowns of government and organized religion, and a moral about the importance of being oneself.

Anyone Can Whistle made it just nine performances on Broadway.

When Shakespeare doesn't rock

Owing to the success of Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell, Broadway in the 1970s became the age of the rock musical. As those two were new, edgy, youth-oriented takes on some very familiar material (the biblical stories of Jesus Christ), the producers of Rockabye Hamlet took a similar approach, presenting a show based on William Shakespeare's well-known Hamlet but updated for the age of the electric guitar.

Originally conceived as a radio play called Kronberg: 1582, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, Rockabye Hamlet uses Shakespeare's plot — tormented Danish prince tries to kill his king stepfather and expose the murder of the old king, his father — but little of the Bard's famous dialogue. Why should composer and scriptwriter Cliff Jones copy-paste, "That one may smile and smile and be a villain," when he could conceive of lyrics like "Good son, you return to France/Keep your divinity inside your pants." At least there were some future stars in the cast — Beverly D'Angelo (Vacation) portrayed Hamlet's mentally ill girlfriend Ophelia, and future rock star Meat Loaf played a priest. Rockabye Hamlet said goodnight sweet prince to Broadway's Minskoff Theatre in February 1976 after a mere seven performances.

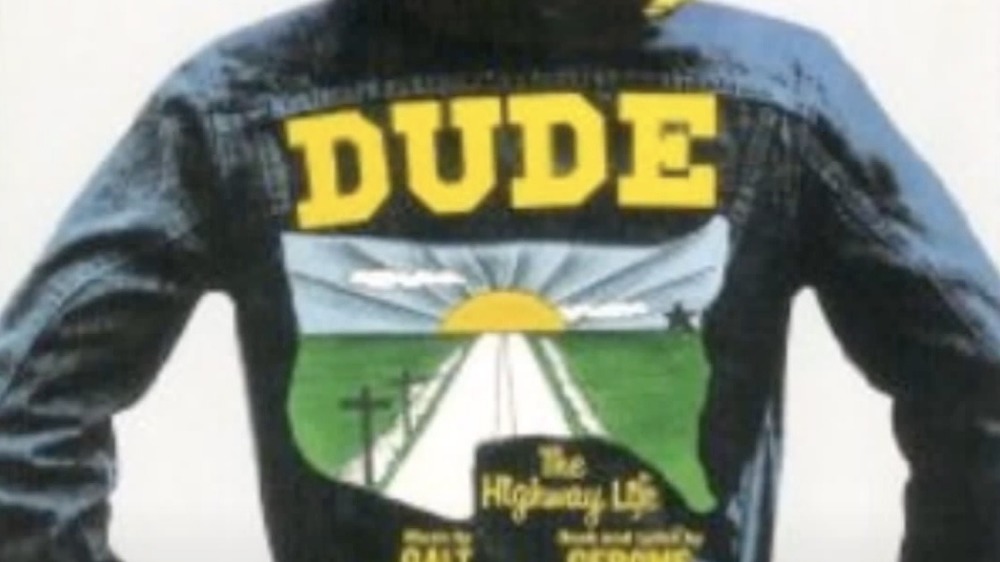

Dude, where's the plot?

After he captured the hippie zeitgeist with Hair, playwright Germome Ragni returned with 1972's Dude (The Highway Life), a show so convoluted that members of the cast and crew couldn't figure out what it was supposed to be about. The first draft of the musical was 2,000 pages long and "remained a mass of undoable nonsense," according to star William Redfield. According to author Ken Mandelbaum, the plot was a confusing, hard to follow mixture of religion and reality bending about actors named Harold and Reba, who, thinking they're about to stage a Shakespeare play, are sent to a place much like the Garden of Eden, where Satan and "Guide #33" (God) try to win sway over the soul of their son, Dude, who becomes an adult and falls prey to the temptations of drugs and sex. At the end, Guide #33 swoops in to say that everything is fine, because life is just a play.

"It was chaotic, disorganized," a crew member told The New York Times, which predicted that Dude "may go down in theatrical history as Broadway's most monumental disaster." It's astounding it ever opened at all — just weeks before its scheduled debut, Dude producers fired the director, choreographer, and costume designer, and toyed with the idea of canceling the show entirely, forcing Ragni to write a new second act. The whole thing lurched onto Broadway, but it didn't last. Dude hit the road after 16 performances.

Carrie was a bloody disaster

Some of the biggest musicals in Broadway history originated as books and were successfully adapted to the big screen, too, like Les Miserables and My Fair Lady. Not included in this club – Carrie, the first published novel in the wildly successful career of horror author Stephen King, which became a hit film in 1976. It's one of King's most gruesome tales, about an abused teenager named Carrie White who uses her telekinetic powers to lay bloody waste to her classmates — particularly after they dump pig blood on her at a dance. Now, imagine all of that playing out as a Broadway musical.

According to the The New York Times, Carrie opened in 1988 after many delays incurred when backers pulled out and management changed hands. Director Terry Hands, composer Michael Gore, lyricist Dean Pitchford, and Linzi Hateley, starring as Carrie, had zero Broadway musical experience between them. Altogether, it cost $7 million to stage Carrie, one of the most expensive Broadway shows ever to that point.

The show itself — not good, according to The New York Times theater critic Frank Rich. He called out the show's "uninhibited tastelessness" and marveled at the number about pig slaughter. "No expense has been spared in bringing the audience some of the loudest oinking this side of Old McDonald's Farm," Rich wrote. After Rich's review and word of mouth spread, Carrie was over. It closed after just five performances.

Into the Light qucikly went dark

The Shroud of Turin is a mysterious artifact that for many years was believed to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, until scientific testing largely disproved the notion, reports History. That interplay between science and religion and reason and faith formed the basis of the 1986 musical Into the Light. Dean Jones, an actor best known for performances in ultra-lightweight live action Disney fare like That Darn Cat! and The Love Bug, lead the cast as James, a genius physicist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory who gets to embark on his dream experiment — trying to determine whether or not the Shroud of Turin is an authentic Christian artifact. Into the Light is thus a musical about the nature of belief and scientific testing, neither of which are terribly outward or theatrical concepts.

Into the Light did offer plenty of theatricality however, in the form of dancing nuns, a light scheme that made heavy use of green lasers, and a fantastical character. James' son, neglected by his work-obsessed father, pals around with his imaginary friend — a mime. The lyrics to the show's songs mixed explaining scientific phenomena like quarks and antimatter with head-scratching philosophy and goofy humor. Into the Light contains the lyric, "When you stand in the dark, you cannot see a thing," as well as, "Why did God create anchovies if everyone hates them?" The lights went on for Into the Light in October 1986 and then they were turned off after six performances.

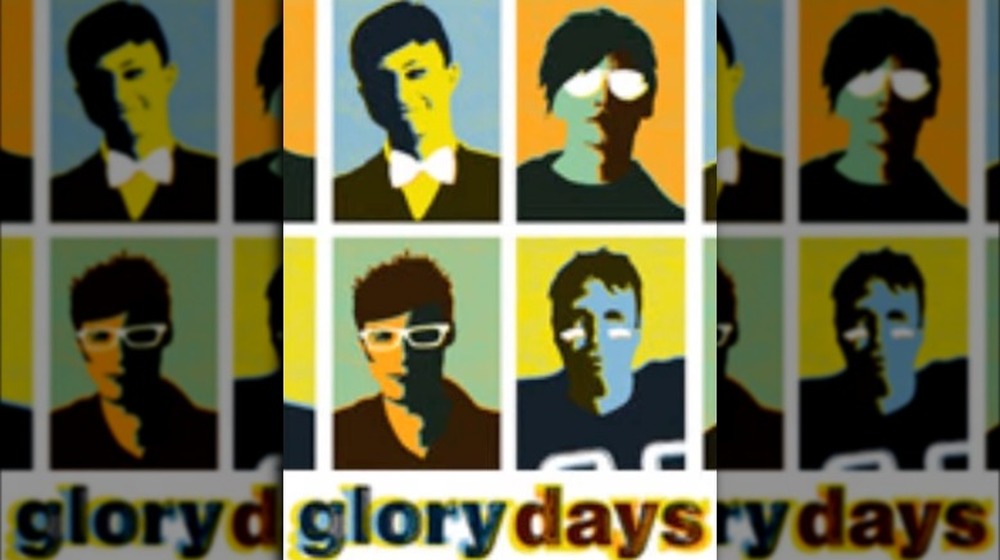

Glory Days for just one night

The 2008 Broadway musical Glory Days seemed like it had a relatable if not universal concept at its heart. It was about four friends who meet on their old high school's football field a year after graduation to catch up, share their anxieties, and to just talk about life as they stand at the precipice of adulthood. That's a scenario millions have experienced, but it's also a very personal one and maybe one not strong enough or appropriate for a grand Broadway musical. According to Playbill, Glory Days was the work of playwright James Gardiner and composer Nick Blaemire, who, at age 24 and 23 respectively, weren't much older than their characters, lending an air of credibility and authenticity to the show. Glory Days earned acclaim and full houses during its premiere run in Arlington, Va., leading big-time producers to port it to the Great White Way.

Critics were not wowed by the Broadway version. Variety called Glory Days a work of "immature self-indulgence," while TheaterMania said audiences would find it "laughably inconsequential." Those damning reviews of preview performances, along with shockingly low advance ticket sales, meant Glory Days would not enjoy many glorious days on Broadway. It's opening night was its closing night — Glory Days played to paying audiences just one time.

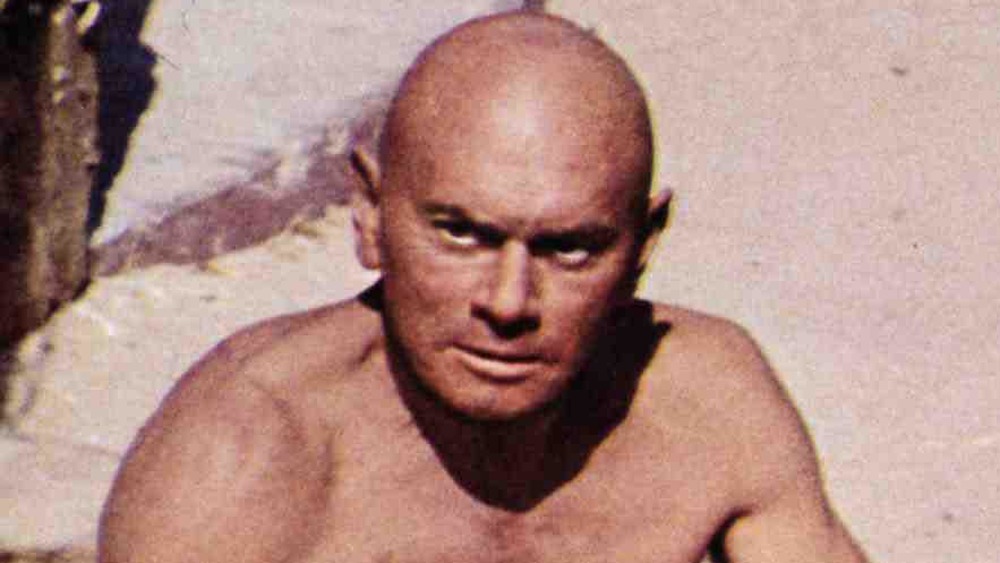

Not even the king could save Home Sweet Homer

There's no shortage of plot or adventure in The Odyssey, the Ancient Greek epic poem by the man known only as Homer, that follows warrior Odysseus's difficult, years-long quest to make it home to his wife after the Trojan War. When that became the musical Odyssey in 1975, the assembled creative team featured some heavyweights. Erich Segal, author of the bestseller Love Story, handled the script and lyrics while producers secured the talents of Yul Brynner — best known for his title role in The King and I on film and on Broadway — to star as Odysseus.

Before hitting the New York stage, Home Sweet Homer toured the United States under the name Odyssey, but Brynner wound up a poor choice for the production. He frequently missed shows, claiming to be too sick to perform due to the prolonged effects from a case of food poisoning he claims to have suffered after eating tainted ribs at a Trader Vic's restaurant in 1974.

After some unauthorized script revisions, Segal took his name off the show, per The New York Times, and producers sought to cut their losses by attempting to cancel the scheduled Broadway run. They couldn't entirely do that, however, because Brynner reminded them that his contract guaranteed at least one show in New York. And so, Odyssey, goofily retitled Home Sweet Homer, played at the Palace Theatre exactly once, on Jan. 4, 1976.

Few wanted anybody to Bring Back Birdie

Sequels to stage musicals are relatively rare. Broadway shows are usually self-contained entertainments with a beginning, middle, and definitive end with no story left to tell. Plus, audiences have to be familiar with the predecessor show, which isn't a guarantee anyway, especially if the musical ran on Broadway years earlier and with a different cast at that. It's much easier and more of a guarantee of success to just revive a beloved musical rather than stage a continuation of one — and Broadway producers might be loath to do one because of the stunning lack of success of the most prominent musical sequel, 1981's Bring Back Birdie.

Bye Bye Birdie, debuting in 1960, was a take on the Elvis Presley phenomenon of the 1950s. In the show, a rock n' roll star named Conrad Birdie was about to ship off for military service but not before his handlers arranged a publicity stunt where he'd kiss one lucky teenage female fan. It ends with Birdie drafted and his music publisher Albert marrying his long-suffering girlfriend and leaving showbiz. In Bring Back Birdie, writes author Ken Mandelbaum, set 20 years later, TV producers offer Albert a fortune if he can find Birdie and put him on TV, as the rock star has disappeared, gained weight, and become the mayor of a small town. It turned out audiences didn't really need to know what happened next to Albert and Birdie, because Bring Back Birdie went away after four performances, according to Playbill.

Via Galactica was totally far out

Well before he played Gomez Addams in two Addams Family movies, Raul Julia starred in more than a dozen Broadway productions, including a wild, 1972 sci-fi hippie extravaganza called Via Galactica. Conceived by Hair composer Galt McDermot and lyricist Christopher Gore, the show is about a group of totally groovy long-hairs, who all had vague character names like "Roustabout," "Blue Person," "Storyteller," and "Entertainer" — except for Julia's character, leader Gabriel Finn — who hitch a ride on an asteroid in the year 2972 in search of a totally far-out planet where they can establish a utopia called New Jerusalem.

To approximate the weightlessness of outer space and the surfaces of distant worlds, the stage at the Uris Theatre was outfitted in trampolines — and the cast members bounced on them for the entirety of the show (when they weren't flying around on rigging and when it worked, that is), as per Gizmodo. Considering that Via Galactica was about, and for, hip, young people and debuted in 1972, one would presume the musical would feature a rock score, but it doesn't — it's a country musical. That's a lot going on in just one musical — too much, perhaps. Via Galactica blasted off after seven Broadway performances.

Dance a Little Closer was a musical about nuclear war

The most popular Broadway musicals offer entertainment and escapism. People generally don't want to pay those famously high Broadway ticket prices for a stone-cold bummer. That's likely a big part of why Dance a Little Closer bombed so thoroughly in 1983. It certainly wasn't an amateurish production, with a script and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, the man responsible for classic musicals like Brigadoon, My Fair Lady, and Camelot, and a score from Charles Strouse, composer of Bye Bye Birdie and Annie.

Dance a Little Closer was a music-added, updated-for-the80s version of Robert E. Sherwood's play, Idiot's Delight, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama way back in 1936. Regular plays tend to be heavier and more sedate than musicals, particularly the ones with thought-provoking content and important enough to win the Pulitzer. Idiot's Delight is a dramedy that takes place in an Italian mountain hotel, where guests from England, Germany, France, and America, are basically trapped as a world war breaks out. In Dance a Little Closer, the horrific event is the dawn of what looks like a nuclear apocalypse.

What could have been a terrifying and uncomfortable night of singing and dancing about the end of the world turned out surprisingly bland. New York Times drama critic Frank Rich said Dance a Little Closer was an "extravagant mishmash" that "numbs the audience with almost every step." At least the audience was small – Dance a Little Closer lasted one night on Broadway.