The Most Horrific Wrongful Convictions In U.S. History

While it's impossible to know how many people in the United States are imprisoned for crimes that they didn't commit, even the most conservative estimate of one percent of prisoners amounts to around 20,000 people. There are many ways that retributive justice begets harm, and wrongful convictions are just one example.

Between 1980 and 2019, over 2,400 people have been exonerated nationwide, and there are many organizations such as The Innocence Project and Centurion Ministries that continue to work toward exonerating those who have been wrongfully convicted. However, countless people have been executed as a result of their wrongful convictions throughout history, and an unknown number have died while imprisoned. For these people, posthumous pardons have a hollow symbolism.

And even for those who get pardoned or exonerated during their life, no matter how much money they get from the state as compensation, nothing can give back the years lost or take away the memories gained. However, exonerating the wrongfully convicted is imperative. It's estimated that at least four percent of people on death row are innocent, and in the United States, Black people are more likely to be wrongfully convicted, adding another layer to the racial disparity in mass incarceration. Although these are just the tip of the iceberg, here are some of the most horrific wrongful convictions in U.S. history.

Ignoring the rules of war

In 1854 and 1855, Isaac Stevens, the governor of Washington Territory, forced different Native groups to sign over their land. According to Wicked Seattle by Teresa Nordheim, the Nisqually weren't the only ones displaced. The Yakima, Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and the Nez Perce had to sign over parts of their reservation as well. Leschi, leader of the Nisqually tribe, was one of many who objected to the terms of the treaty, and many claim that he signed under protest. Others claim that the "X" next to his name was forged, although this is disputed.

Despite the treaties, white settlers continued to invade Native land. Led by the Yakima, Native tribes retaliated during the Yakima War, which lasted from 1855 to 1858. Leschi, who was half-Nisqually and half-Yakima, allied himself with the Yakima and led "probably 300 troops" against the United States during his time in battle.

In History of American Indians, Robert R. McCoy and Steven M. Fountain write that on October 31, 1855, Colonel Abrams Moses was murdered. Governor Stevens immediately blamed Leschi for the murder, despite the fact that he was miles away. And even though the U.S. Army "recognized the engagement as a battle and informed Leschi that he could not be tried for any crime," Leschi was found guilty by an all-white jury and hanged for murder on February 19, 1858. Almost 150 years later, Leschi was exonerated in 2004.

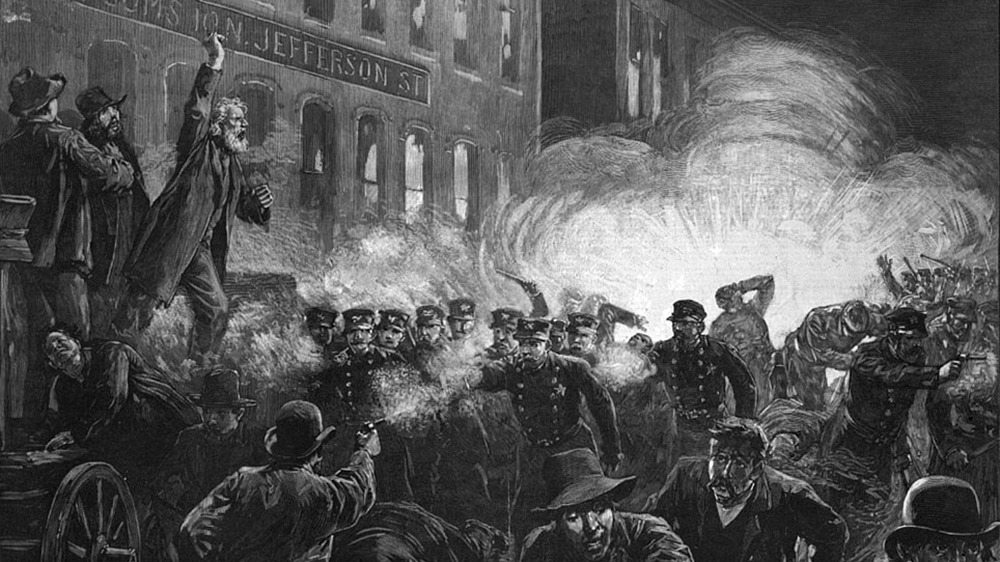

Rounding up the anarchists

On May 4, 1886, a bomb went off in Haymarket Square during a public rally held by labor activists and anarchists. The rally itself was for the six unarmed strikers who'd been murdered the previous day during a skirmish with police at Chicago's McCormick Reaper Works factory. Eight people died from the bomb, with 67 wounded, and as the police attacked the crowd, 200 more were injured. No one knows exactly how many more were killed.

Even though multiple people identified Rudolph Schnaubelt as the culprit who threw the bomb, he was never charged. Instead, eight men, almost all of whom were immigrants, were indicted for conspiracy, since there were enough witnesses to prove that they hadn't thrown the bomb. According to Pitzer College's Anarchy Archives, August Spies, Louis Lingg, Albert R. Parsons, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, and Oscar Neebe were all found guilty. But while Neebe was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment, the others were sentenced to death by hanging. Even though Neebe accurately claimed that there was no evidence tying him to the bombing, during his sentencing, he said to the judge "I am sorry I am not to be hung with the rest of the men."

The sentences of Fielden and Schwab were later changed to life imprisonment, and Lingg committed suicide. Spies, Parons, Engel, and Fischer were executed. According to PBS, in 1893, Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining victims of the Haymarket Trial.

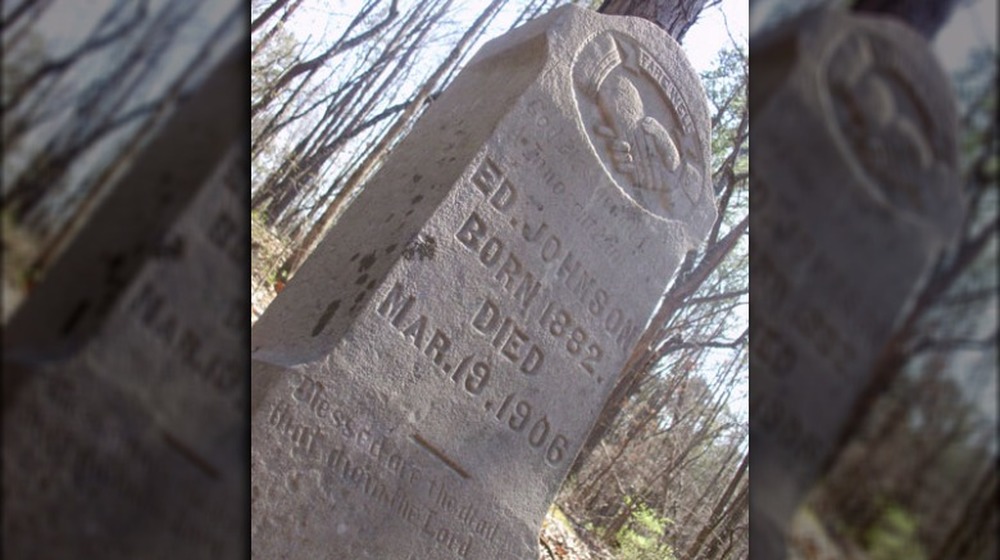

Injustice never waits

In 1906, Nevada Taylor, a white woman, was attacked and raped on her way home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She identified Ed Johnson, a Black man, as the rapist in a darkened interrogation room, but in both of her testimonies during the trial, she refused to swear that Johnson was actually the man who'd assaulted her. According to "Lynching in America" by Maria I. Arbelaez-Lopez, Johnson also testified that multiple people could place him working at the Last Chance Saloon at the time of the assault.

Despite this, on February 9, Johnson was found guilty by an all-white jury and sentenced to death by hanging. But, according to Famous Trials, Noah Parden and Styles Hutchins, two local Black attorneys, got involved and appealed Johnson's case repeatedly until the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear it. In light of the pending appeal, Johnson was awarded a stay of execution, becoming the first Black person in the United States to be issued one by the Supreme Court. And as his lawyer, Parden became the first Black man to appear before the U.S. Supreme Court as lead counsel.

On March 19, Sheriff John F. Shipp received word of the stay of execution and was informed that he was responsible for protecting Johnson until his trial. Instead, according to The Supreme Court, edited by Paul Finkelman, "Shipp and his deputies aided and abetted the lynch mob" that murdered Johnson that day.

Murdered in self-defense

Lena Baker was born in 1900 in Randolph County, Georgia. By 1944, she was doing laundry, cleaning houses, and picking cotton in order to make ends meet for her three children and her mother. One of the people she worked for was Ernest B. Knight, a white man 23 years older than Baker. At some point, Knight began to sexually assault Baker. According to The Black Commentator, when Baker tried to escape the abuse, "Knight locked her in his gristmill for several days at a time."

On April 30, 1944, Knight locked up Baker "for the better part of that day," according to NPR. When he came back and demanded sex from Baker, she refused. He attacked her, and in the subsequent struggle, Knight was shot and killed. Face2Face Africa writes that Baker went to the town coroner immediately after to let him know of the murder. He told her to go to the sheriff, but she just went home "to be picked up by the sheriff later that night."

An all-white, all-male jury convicted her after just a four-hour trial and less than half an hour of deliberations. She was executed by electrocution on March 5, 1945, becoming the only woman ever to be executed in this manner in Georgia. Her last words were, "What I done, I did in self-defense or I would have been killed myself. Where I was, I could not overcome it."

Sometimes it all comes out

On October 25, 1967, James Joseph Richardson's seven children and step-children became incredibly ill after eating lunch in Arcadia, Florida. They all died the next day. According to Justice: Denied magazine, despite the fact that their next-door neighbor Betsy Reese was babysitting the kids and had fed them their lunch, police didn't investigate her as a suspect, focusing instead on Richardson, the children's father.

Richardson, a Black man, repeatedly denied that he'd killed his children, but he was found guilty of first-degree murder by an all-white jury and sentenced to death. After the death penalty was deemed unconstitutional in Florida in 1972, Richardson's sentence was changed to life imprisonment.

Then, in 1988, Belinda Romeo, a nursing assistant who'd cared for Reese over the previous three years, came forward and said that Reese "had confessed to the murders of the children 'hundreds of times,'" likely as a result of her Alzheimer's. It was also found that Reese was on parole for shooting her second husband, and her first husband had also "died after eating a meal she prepared for him, but she was not charged," according to The National Registry of Exonerations.

Evidence was also revealed that the testimonies from jailhouse informants had been coerced, and in light of everything, Richardson's conviction was overturned. He was released in 1989 after spending 21 years in prison. Meanwhile, Reese passed away three years later in the nursing home and was never charged.

Losing 44 years

In October 1971, a woman who worked at the Baton Rouge General Hospital in Louisiana was raped. According to The National Registry of Exonerations, police arrested Wilbert Jones, a 19-year-old Black man, in January 1972, and although the woman chose Jones out of a lineup, "she expressed concern" that Jones was significantly shorter than her attacker and that his voice sounded different.

Despite this, according to Innocence Project New Orleans, Jones was convicted on her identification alone "at a brief trial" and sentenced to life in prison. After the Louisiana Supreme Court ordered a new trial, his conviction was upheld, once more based on the woman's testimony alone.

After Innocence Project New Orleans started reinvestigating the case, they discovered in 2011 that all the physical evidence had been destroyed after the second trial. Nevertheless, they continued investigating and found that another man had committed similar rapes around the same time, one of which was "virtually identical." They also found that the man had been convicted before Jones' second trial, but the police had failed to disclose any of this information to the defense.

In light of the new evidence, Jones' conviction was vacated on October 31, 2017. Although the state appealed to reinstate his conviction, the Louisiana Supreme Court declined, and eventually, the charges were dropped. After spending almost 45 years imprisoned, Jones' incarceration is the second-longest "after a known wrongful conviction in U.S. history."

Exoneration at death's door

After Cheryl Fergeson, a 16-year-old white student, was raped and murdered in Conroe, Texas, in 1980, police arrested janitor Clarence Brandley. Brandley, "the only black man on the [high school's] staff," was interviewed with one of his white co-workers, and during the interrogation, one of the police claimed that someone had to hang for this. Since Bandley was Black, he was "elected," according to Witness to Innocence.

Although no physical evidence linked Brandley to the assault, all the other janitors alibied one another and "reconstructed a version of events that positioned Brandley with the murdered girl at the time of her death." Brandley's first trial was a mistrial, but he was convicted and sentenced to death after his second trial in 1981. Both trials were held before all-white juries.

The execution was set for March 26, 1987, but that year, Jim McCloskey, who founded Centurion Ministries, started working to exonerate Brandley. The execution was stayed five days before it was supposed to happen, and a new trial was ordered. The judge who ordered the new trial stated that "no case has presented a more shocking scenario of the effects of racial prejudice, perjured testimony, witness intimidation [and] an investigation the outcome of which was predetermined."

Brandley was finally released in 1990, and even though the D.A.'s office dropped the charges, since he was never granted a pardon, Brandley was never compensated for the decade he spent on death row.

Antics of the Satanic panic

During the 1980s, the Satanic Panic swept the United States, and several dozens of people, especially those who worked at day care centers across the country, were accused of abusing children. These allegations also came with accusations of horrific Satanic rituals and occult sex acts. But according to Wrongful Conviction in Sexual Assault by Matthew Barry Johnson, unlike the other child sex abuse scandals of the time that originated in day cares, the Kern County accusations were towards local adults in the neighborhood.

The Kern County cases ended up being some of the largest prosecutions during the Satanic Panic. Over 30 defendants were convicted of molesting children, while an additional eight took plea deals. According to the Associated Press, there were claims that over 80 adults had "participated in molestations, devil worship and sacrifices of 29 babies." However, no physical evidence was found, despite authorities dragging two lakes and digging up a backyard searching for bodies.

The most famous convictions were those of Alvin and Deborah McCuan and Scott and Brenda Kniffen, who were sentenced "to a combined 1,000 years behind bars." However, many of the children later admitted that they'd been coerced by prosecutors and social workers into lying about the abuse. As a result, many of the convictions ended up being overturned, although according to Bakersfield.com, some people had been imprisoned for upwards of 25 years. At least one person ended up dying while imprisoned.

Escaping death twice

In 1982, Rebecca Lynn Williams, a 19-year-old white mother of three, was sexually assaulted and murdered in Culpeper, Virginia. According to the Innocence Project, before she died, her only description of her attacker was that he was Black. One year later, Earl Washington Jr. was arrested for an alleged burglary, and after two days of questioning in police custody, the police claimed that Washington had confessed to a number of different crimes, including the murder of Williams.

All five of Washington's "confessions" were riddled with inconsistencies, and he didn't even correctly identify Williams' race to the police. Police also completely disregarded the fact that Washington, a 22-year-old Black man, had a mental disability, and it took four attempts to get a "rehearsed confession," according to The National Registry of Exonerations. Washington was sentenced to be executed in September 1985. But nine days before the execution, Washington's case was granted a stay of execution thanks to lawyers who worked on it pro bono.

Per Death Penalty Information Center, despite the fact that there was seminal and DNA evidence that proved that Washington wasn't the culprit, since Virginia has a "21-day-deadline for reopening a case based on newly discovered evidence," the attorneys had missed their chance for another appeal. As a Hail Mary, Governor Wilder was asked for a pardon, and in 1994, he commuted Washington's sentence to life in prison. In 2000, Washington was finally granted an absolute pardon for the murder.

Mass hysteria's typical targets

Bernard Baran was one of many people who was convicted as part of the Satanic Panic, but his case was notable for the blatant homophobia that was wrapped up in his trial. According to The Bernard Baran Justice Committee, Baran was openly gay and started working at the Early Childhood Development Center in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, when he was 16 years old.

Three years later, in 1984, Baran was arrested for allegations that he had sexually abused five children at the day care. According to The Nation, although the children initially denied having been abused, psychologists used leading questions to get false accusations, while "improbabilities in the children's stories were brushed aside." During the trial, District Attorney Dan Ford, who went on to become a state Superior Court justice, compared being gay to being an child abuser and said that Baran working in the day care was like "a chocoholic in a candy store." Baran maintained his innocence and was thus ineligible for parole.

In 2004, he got a new team of lawyers who were able to prove that the interviews conducted by the D.A.'s office had been incredibly suggestive and leading. They were also able to prove that Baran had received ineffective counsel, who'd also never been informed that sexual charges had been brought against the boyfriend of one of the children's mother's the very day that Baran went to trial. In 2009, Baran's charge was dismissed, and he was freed after 21 years of imprisonment.

Taking advantage of mental illness

In 1976, Michelle Mitchell was murdered in Reno, Nevada, and police had little evidence other than a cigarette butt near the body. But then three years later, according to The National Registry of Exonerations, a staff member at a mental hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana, called the police to say that one of their patients, Cathy Woods, had claimed to be responsible for Mitchell's murder.

Woods, also known as Anita Carter, had a long history of mental illness and had already been diagnosed as schizophrenic when the police went to see her. The information she gave detectives wasn't anything that wasn't already known by the public, and some of her assertions were also "obviously false," like the claim that she worked for the FBI.

During the trial, detectives testified that Woods had said that she was a lesbian and that the murder had occurred when Mitchell had rejected Woods' sexual advances. There was no mention of her mental health. On December 11, 1980, Woods was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

MyNorthwest reports that it wasn't until 2014, when DNA evidence connected Rodney Halbower to the murder, that Woods was finally exonerated and released after 35 years of imprisonment, making her one of the longest wrongfully incarcerated women in the United States. However, the DNA connection only happened because Woods connected with the Rocky Mountain Innocence Project to petition a DNA test in 2013, and the resulting DNA profile was sent to the FBI.