What It Was Really Like As A Medic In The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War has become infamous for the brutal battles fought and lost in the impenetrable heat and claustrophobic thickness of the jungle. Following American soldiers into the line of fire, hoping to prevent them from becoming yet more casualties, were their medics.

Medics trained alongside other troops, but their job in the field was to patch up their comrades when the bullet, grenade, or shell with their name on it found its target. Without body armor or even bulletproof helmets, medics were in as much danger as their comrades — and sometimes more. While soldiers could hunker down during bombardments, the medic ran towards the enemy to find the wounded, often with little more than a few bandages, some morphine, and a pair of blunt scissors, and little to no medical training.

Even when the guns were silent, medics were in charge of soldiers' general health, treating them for diseases from malaria to foot rot and unwelcome souvenirs picked up at brothels. This is what it was really like as a medic in the Vietnam War.

Some medics signed up but others were drafted

According to official United States government statistics, 1,857,304 men were drafted through the Selective Service during the Vietnam War (specifically between August 1964 and February 1973.) After completing basic training in bases around the U.S., some were assigned as combat medics and transferred for ten weeks of medical training, often to Fort Sam Houston in Texas. Most had no previous medical experience. The assignment was simply the luck — or bad luck — of the draw.

Other people who became medics volunteered. Beating the army to the punch and signing up instead of waiting to be drafted gave you more control over which area you worked in. Some volunteer medics saw the job as a way to serve their country, while others believed it would be an opportunity to get medical training they otherwise couldn't afford, as Vietnam combat medic Rafael Matos wrote in The New York Times.

Becoming a medic was also an option for conscientious objectors who had been drafted. You had to apply for conscientious objector status when signing up for the draft. If your application was denied, and you still refused to fight, you could be sent to military prison, as Vietnam combat medic Ben Sherman found out. Fortunately, his captain felt that having a soldier who refused to fight would not be ideal in a battle situation and persuaded the Pentagon to issue Sherman conscientious objector status and assign him as a medic.

Medics were both different and similar to other soldiers

Like other soldiers, combat medics were trained in fitness drills, firearms (unless they were conscientious objectors), and how not to get shot. Medical training lasted ten weeks and revolved around triaging battle wounds.

Vietnam combat medic Stephen Dunn recalled learning "how to give shots, bandage and carry the injured, apply tourniquets and morphine." Fellow Vietnam combat medic Roger Buchta said medics also learned how to treat shock and administer an IV, as well as basic anatomy. After that, the medics worked at base clinics until receiving their orders to deploy to Vietnam.

Unlike in other wars, Vietnam medics carried weapons. According to We Are the Mighty, most had an M16A1 rifle, a .45 caliber pistol, and grenades. Like the infantrymen, they didn't have body armor or bulletproof helmets.

Medics were also distinct from infantrymen in some ways. Vietnam combat medic Rafael Matos wrote in The New York Times that they didn't have to worry about their appearance, and they didn't have to take orders that conflicted with lifesaving care. Medics weren't supposed to fight, although Matos says he was ordered to perform at least one infantry-related task. Vietnam combat medic Wayne Smith admitted that the heat of battle got to him. "I wanted to be a medic to save lives... But when I was in combat I was tainted by this blood lust and I, too, became a combat soldier."

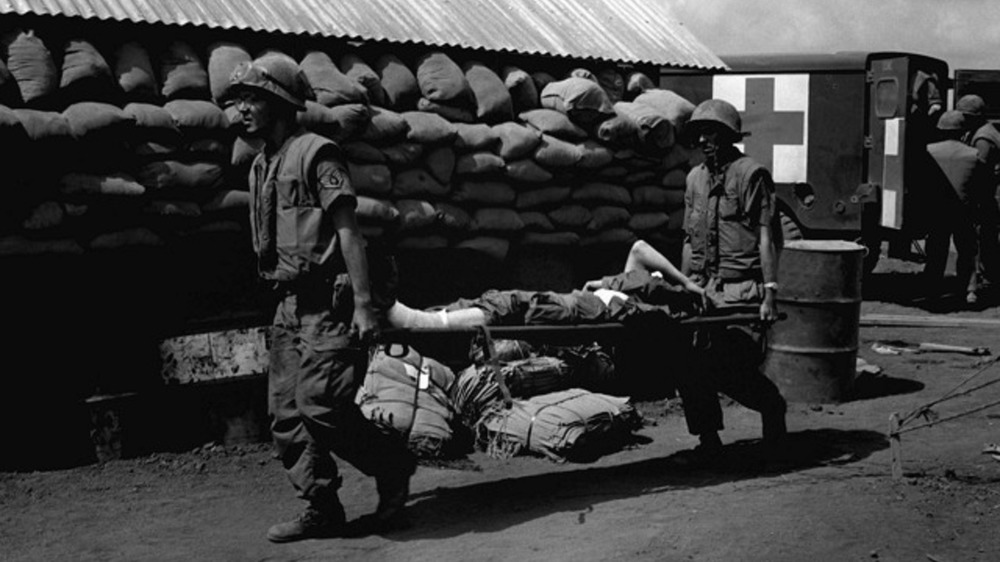

Medics followed soldiers into battle

Mandatory deployment to Vietnam lasted one year, with the option to extend. In theory, medics were supposed to spend some of their deployment working in hospitals on the edge of the battlegrounds or slightly further out and some of it following soldiers into combat. However, they were usually sent wherever they were most needed, which typically meant being attached to a regiment completing missions in the line of fire.

This was especially true during the brutal and deadly Tet Offensive. In fall 1967, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) — the army of North Vietnam — began artillery bombardments against U.S. troops stationed in the highlands, near Laos. This was followed in January by multiple surprise assaults on south Vietnamese cities and government buildings and bases belonging to South Vietnam's Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and the American armed forces.

Writing in The New York Times, Vietnam combat medic Rafael Matos of the First Armored Division explained that during the Tet Offensive, he and his fellow three medics were constantly on duty. They followed the soldiers into battle, fixed up the injured as much as possible, and tried to get them to safety. "Our job now was to tend multiple gunshot wounds, apply tourniquets to the stumps of legs amputated by mines, and bandage shrapnel-mutilated bodies... Bullets zinged around us... Death became a daily reality, as we zipped our fallen comrades into body bags," Matos wrote.

Medics carried out day-to-day medical duties

Fortunately not every day as a medic in Vietnam meant running into battles and treating grievously injured soldiers. When they were relatively remote from the action or in times of relative peace, the medics focused on caring for the soldiers' general health. In the jungle, that meant reminding soldiers to take their malaria tablets and stay hydrated. In The New York Times, Vietnam combat medic Rafael Matos recalls mundane tasks like administering tetanus shots and treatments for head lice.

Many soldiers encountered one particular health issue while stationed on bases further out. In 1968, Dr. David Cromwell was a licensed doctor in Maryland, a qualification that allowed him to direct commission as an officer and physician. Later in the war he was sent to the Ashah Valley, but for his first few months he ran a clinic at a base in Saigon, where the most common complaint was sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), often picked up from brothels.

However, Cromwell says, for soldiers trekking through the jungle, the most common ailment — aside from artillery and bullets — was foot or jungle rot. Caused by having wet feet for a long period of time, this could be prevented by changing into dry socks as often as possible and was easily treatable if caught early. However, Cromwell noted, some soldiers felt that staying quiet and losing a toe was a small price to pay for escaping back to the U.S.

American medics serving in Vietnam didn't only treat Americans

As well as caring for American soldiers, the medics treated South Vietnamese villagers and even prisoners of war. A study in the American Medical Association's (AMA) Journal of Ethics explains that with South Vietnamese doctors dispatched to military hospitals, civilian populations were left without healthcare. As a way of getting into their good graces, the AMA and U.S. Agency for International Development collaborated on the Volunteer Physicians for Vietnam (VPVN) Program, recruiting American physicians to work in Vietnam's civilian hospitals. In addition to treating conditions like parasites, tuberculosis, typhoid, dysentery, and war-related wounds, the physicians passed on their medical knowledge to Vietnamese doctors and nurses.

The goodwill didn't always work. Vietnam combat physician Dr. David Cromwell recalled that on one occasion, the building the villagers had given permission for his team to work from had been booby trapped with a tripwire.

Medics not associated with the program were also assigned to treat locals. Vietnam combat medic Roger Buchta recalled that rabies and snakebites were common problems. His fellow combat medic veteran James Cruz was sent to a refugee camp in the mountains. In an oral history of his experience, he said, "We could dispense [medicine], we could do anything we needed because these people had nothing else... The guys before me had delivered twins... The other medic and I had free range to do what we needed to." They even did much-needed but grizzly dental work.

The medics' job was to patch soldiers up in the field

Medics went into battle with very limited supplies – as many bandages, gauze rolls, and morphine syringes as they could carry or persuade others to carry, and possibly an IV bag and a pair of scissors. According to Dr. David Cromwell, physicians didn't get more than a stethoscope.

The phrase "BandAid over a bulletwound" is grimly close to what they were able to accomplish. But the combat medics' purpose was to patch up their comrades well enough that they could be moved to an area accessible by helicopter.

Gary Michael Rose was a Special Forces combat medic who received the Medal of Honor in 2017 for saving the lives of 60-plus men over a four-day mission in Laos in 1970. He told the Army's website, "Your job, as a medic, is to maintain the person's life. That is, to keep them out of shock, to stop the bleeding, and also as much as possible prevent infection if you could."

From the battlefield, the wounded would be medevaced to an aid station, which had more resources to deal with severe injuries. From there, the worst cases would be flown on to a more remote and better equipped hospital, for example in Saigon, or even to a ship hospital like the U.S.S. Sanctuary, anchored mainly in Da Nang. Those who recovered were often sent back out to fight again.

Vietnam combat medics had an alternative to pain medicine

Combat medics in Vietnam often weren't able to carry enough morphine to relieve every injured soldier's pain. Vietnam Special Forces combat medic Gary Michael Rose told the Army website that under heavy fire, he could only give the wounded enough morphine to help them walk without assistance. Otherwise he'd have to find people to carry them, who then wouldn't be able to shoot back at the enemy, which could ultimately result in more casualties.

"It's not like a hospital where the doctor and the nurse are trying to make you comfortable... I'm trying to take the pain away just enough where you are not going to be screaming or moving around or jerking," he said.

According to NPR, this scarcity of supplies led Vietnam medics to resort to using M&Ms as a placebo. The candy had been popular with soldiers since World War II. This claim is repeated in Vietnam veteran Tim O'Brien's semi-autobiographical short story collection, The Things They Carried. In particular, medics may have used M&Ms when they had determined that someone probably wasn't going to survive, instead of wasting precious morphine.

The medevac helicopter missions were nicknamed Dustoffs

Medical evacuation missions carried out by UH-1 Iroquois helicopters ("Hueys") became known as Dustoffs, after a call sign used by the first iteration of this type of helicopter in the 57th Medical Detachment. They were crewed by four people — a pilot, an aircraft commander, a medic, and a crew chief. When they landed, the medic and crew chief were responsible for loading the wounded into the back on litters, where they could administer further first aid, including blood transfusions and fluids via IVs.

Addressing the Congressional Committee on Veteran Affairs in 2003, Retired Chief Warrant Officer Michael J. Novosel, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for a mission in Vietnam, said of the Dustoff crews he'd worked alongside, "To appreciate the sacrifices they made, one has to understand the magnitude and intensity of the task... They kept men with traumatic amputations, sucking chest wounds, bullet riddled bodies alive... They were under intense physical and mental pressure."

Flying into the middle of battles in the chaos of the jungle, the Dustoff crews were at a high risk of getting hit, either with a bullet or artillery. The casualty rate is estimated to have been as high as a third. Unsurprisingly, these crews — like all combat medics — were highly respected by soldiers. However, as Novosel explained at the 2003 hearing, because Dustoff crews are technically assigned to aviation units, they still are not eligible for the Combat Medic's Badge.

Medical advances made in the Vietnam War are still used today

The use of medevac helicopters to provide in-transport medical care in the Vietnam War saved countless lives. Dustoff missions alone picked up an estimated 900,000 wounded soldiers and Vietnamese civilians during the course of the war. The success of this approach has inspired emergency medical respondents around the world — military and civilian — to rely on helicopters as a fast mobile operating theater where the next stage of medical treatment can start even before reaching a hospital.

The Vietnam War also led to advances in the storage, transport, and use of blood. Predictably, the need escalated in line with the casualties — from 100 units per month in 1965 to more than 30,000 units per month by 1968 (during the Tet Offensive), according to a report from the Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program.

This was the first time blood type O negative had been used for universal donations — which it still is today. In addition, a new type of container had been developed that could keep blood viable for 48 to 72 hours in the field — long enough to move it to hospitals near the frontlines. Medical researchers in Vietnam also experimented with adding small amounts of adenine, an amino acid, which extended blood's viability to 40 days. To maintain the supply, the U.S. Army Pacific and U.S. Army Republic of Vietnam (USARV) built a donor and distribution system traversing the U.S., Japan, and South Vietnam.

There were thousands of female medics

According to The Washington Post, as many as 15,000 women served in Vietnam with the U.S. military. Most were nurses working in combat hospitals. Even away from the battlefield, combat medicine wasn't an easy job. Nurses worked 12 hours a day, six days a week, caring for soldiers with horrifying injuries. Adding to the challenges, some of the makeshift hospitals had no running water or air conditioning.

Many of the nurses came straight from nursing college, with no practical experience of emergency nursing, let alone combat nursing. Former U.S. Army nurses Diane Carlson Evans and Marsha Four, who both served in Vietnam, explained that part of their anxiety about being in the war zone was that their under-preparedness would result in soldiers' deaths. "To say 'challenging' doesn't come close to the feelings that I had about being incompetent. Their lives were in my hands. I was responsible for them," Four later told Whyy.

After their tours, many nurses — like many medics and soldiers — struggled to readjust to life in the U.S. In addition to dealing with repressed emotional trauma, they found civilian nursing frustratingly unchallenging, hampered by regulations that prevented them from performing basic tasks they'd done every day in the field.

In 1984, Carlson Evans launched a campaign for a memorial to the women who'd served in Vietnam, which was finally approved and unveiled near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in 1993.

19 Vietnam combat medics were awarded the Medal of Honor

Many combat medics who served in Vietnam acted with immense courage under terrifying circumstances. They put their own lives in danger to save their comrades, even after they'd sustained injuries themselves. Some were nationally recognized for their heroism. According to the U.S. Army Medical Department, 19 medics who served in Vietnam have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military honor. Eight of these medals were awarded posthumously.

Among the recipients was Thomas Bennett, who was killed in February 1969 while trying to save a wounded soldier during heavy fire. Bennett has the distinction of being the second conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor. The first was Desmond Doss, who was honored for his actions at the battle of Hacksaw Ridge in World War II.

In some cases, it took decades for these medics to receive recognition. (Some Vietnam combat medics arguably still haven't.) For example, according to Forbes, Vietnam combat medic and retired Lt. Col. Alfred Rascon finally received the Medal of Honor he'd been nominated for in 1966 in 2000. Two combat medics received their Medals of Honor in 2017 — army medic James C. McCloughan and Special Forces medic and retired Army captain Gary Rose.

Many medics were traumatized

Medical staff who served in Vietnam felt the immense responsibility of treating soldiers with terrible injuries, often while under fire themselves, and with very little equipment or training. Some also witnessed atrocities carried out by their own side, as Rafael Matos wrote in The New York Times.

Many experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychological issues — not to mention long-term effects of chemical weapons like Agent Orange. As nurse Diane Carlson Evans explained to The Washington Post, medical staff learned to repress their emotions at the time so they could do their jobs. Her friend and fellow veteran nurse Edie Meeks said, "You had to shut your emotions down... There were so many traumatic things that happened."

As sentiment in the U.S. turned against the war, the hostile attitudes of American civilians towards veterans prevented many from finding an outlet once they were home. Many were haunted by nightmares, memories of specific incidents or soldiers they'd lost, and suicidal thoughts. In 2018, Matos wrote, "Unexpected flashbacks still haunt me... I can go into stress if I smell a rare steak... I can suddenly imagine the stench of gunpowder and cordite in the air."

Through therapy, new jobs, veteran centers, and more surprising sources, former medical staff of the Vietnam War found their way back to civilian life. But as Vietnam nurse Joanie Moscatelli told Whyy, "I don't think the war ever ends."