The Messed Up Truth About 19th Century Murderess Mary Ann Cotton

People just can't seem to tear themselves away from the bloody drama of a serial killer, no matter how much many of us try to pretend otherwise. However, the BBC points out that you're not alone. Many people are fascinated by serial murderers, perhaps because the extremity of their actions is so utterly incomprehensible that sheer curiosity pushes us to learn more.

Though many killers are male, it turns out that women have turned to serial murder as well. According to Psychology Today, female serial murderers often have a drive that's pretty distinct from their male counterparts. Many seem to act out their crimes in stealthier ways, often using poison and frequently for attention, sympathy, financial security, or some combination of the above.

That description fits Mary Ann Cotton very well indeed. This 19th century English woman is one of the earliest confirmed female serial killers in recorded memory. She went undetected for decades, apparently killing a succession of husbands, children, and stepchildren with arsenic, then a readily available poison. After she was finally apprehended in 1872, some estimated that she may have killed as many as 21 people, according to Britannica. She was only ever convicted for the murder of one, though it led to her execution by hanging in 1873.

Though she's been gone for nearly a century and a half, Cotton remains one of the most shocking female killers in modern history. Here's the messed-up truth about this notorious 19th century murderess.

Mary Ann Cotton started life as a regular girl in tough circumstances

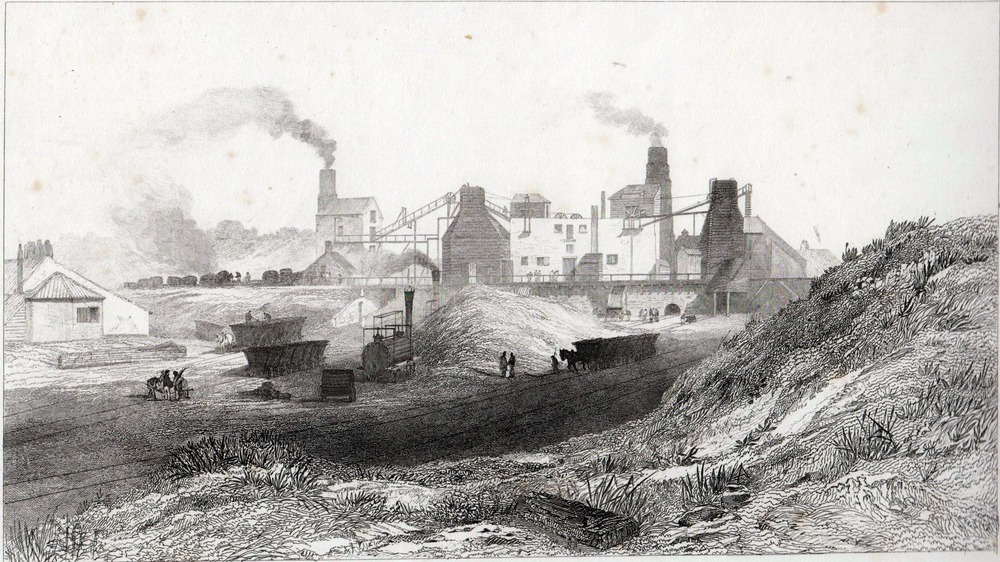

At the beginning of it all, the girl who would become Mary Ann Cotton seemed, frankly, pretty unremarkable. Born in October 1832 in County Durham, England, Cotton was the daughter of Michael and Margaret Robson. According to Mary Ann Cotton, her father was a coal miner. Though he appears to have worked as a skilled laborer who opened new mining shafts, the Robsons were working class.

For many people in Victorian Britain, being born into a working-class family meant that one's life was often touched by tragedy. Cotton was no exception. As per History Collection, her younger sister Margaret died in 1834, when Cotton would have been only 8 years old. Her father died eight years later in a mining accident.

This left their widowed mother in a difficult situation. Though, as the Journal of Victorian Culture reports, there was some financial relief available to widows, it was often highly restricted. For women of the working class, the sudden death of a husband could easily throw them into devastating poverty with little way out. That's likely why Cotton's mother quickly remarried, in order to keep her family away from the horrifying poverty and harsh conditions of Victorian workhouses.

Cotton's first husband and children died of suspicious gastric fever

Mary Ann first Cotton left home at only 16 years old to work as a nurse, according to Britannica. She came back home three years later, taking up work as a dressmaker. A short time later, she married William Mowbray in an 1852 ceremony. The couple would go on to have at least eight children, though, by the time they had settled into a home in Hendon, England, in 1856, some had already died of what was termed "gastric fever." The so-called fever mimicked the symptoms of arsenic poisoning, a fact which would later prove interesting to investigators.

Things seemed to grow worse for the family after Mowbray took out life insurance policies on himself and their three remaining children. Soon enough, he and two of the children also died of "gastric fever." That left Cotton and her daughter with an insurance payout of some £35, according to Mary Ann Cotton, Dark Angel. Rather quickly, she sent the daughter to live with her own mother, Margaret, and set out on her own once again.

Her second husband died a year after the wedding

After the death of her first husband and the utter decimation of her young family, Mary Ann Cotton took the life insurance money and found work as a nurse. She also began a relationship with Joseph Nattrass, History Collection reports, though the affair never resolved into marriage. Cotton had rather more luck at work, where she came across a patient named George Ward.

It's not entirely clear how the two connected while Cotton was caring for Ward, but there must have been at least some semblance of a spark there. As per Female Serial Killers, the two were married in 1865, shortly after he was discharged from the hospital. As Ward was still recovering from his illness, he collected relief payments instead of working, while Cotton moved into the role of primary earner for their household.

Perhaps that's why Ward fell sick again not too long after the wedding and before they could conceive a child together. He died in October 1866, baffling doctors on his way out. Like many of the other dead people in Cotton's wake, Ward presented symptoms that were alarmingly similar to arsenic poisoning. Yet, according to Female Serial Killers, his cause of death was listed as cholera and typhoid. Cotton collected another insurance payout and moved on.

Mary Ann Cotton's poison of choice was arsenic

Though many of the people around her hadn't caught on to Mary Ann Cotton's murderous ways by the time her second husband had died, it's now rather obvious to people who have her whole story that she was using arsenic. Yet, she wasn't alone. During the Victorian era, arsenic was seemingly everywhere, to the point where it became the murderer's poison du jour.

Why arsenic, though? According to the British Library, that's because it was alarmingly easy to access. Some substances, like cyanide and strychnine, were also readily available but produced obvious results. Arsenic, however, was more subtle. It had no taste, no odor, no color, nothing that would alert the potential poison victim to its presence in their food or drink until the substance had already begun to take effect. Plus, it really was everywhere, from the green dye in clothes, to wallpaper, to rat poison. One could simply walk down to the corner shop and buy enough arsenic to kill a man a few times over. Though Britain passed the Arsenic Act of 1851 in an attempt to control the distribution of this deadly substance, it's clear that it wasn't all that difficult for Cotton to keep acquiring arsenic in her drive to kill the people around her.

Mary Ann Cotton's third husband got suspicious of her

After George Ward's death and the subsequent insurance payment, Britannica reports, Mary Ann Cotton became a housekeeper for widower James Robinson in 1866. Soon after she entered the home, Robinson's infant son died of — yes, you guessed it — "gastric fever."

According to Mary Ann Cotton, Cotton wed Robinson in 1867. Her mother, Margaret, died after Cotton visited the woman in March 1867. She officially died of hepatitis, though she died just over a week after her daughter came to tend to her. Cotton took her daughter, Isabella Jane, who had been living with Margaret, with her. Isabella lasted a few weeks until she died of "gastric fever," and she was soon followed by two more of Robinson's children, who succumbed to "continued fever" and yet another case of "gastric fever," according to death records. All three children had been subjects of small life insurance policies. When Cotton gave birth to her and Robinson's child, her infant daughter quickly died of "convulsions." Their next child, George, was one of the rare few of Cotton's children who would survive her.

In 1869, Robinson discovered that she was stealing from him and reportedly kicked her out. Before their final break, Cotton had attempted to get Robinson to insure both himself and the remaining children. Whether or not he suspected his wife of something worse than fraud isn't clear, but we do know that Robinson refused, saving their lives.

Mary Ann Cotton likely killed for money

As Discover Magazine reports, the great majority of female serial killer appear to murder for money. Perhaps, to Mary Ann Cotton's mind, if she tried to settle down without killing for insurance money, she would be putting herself in a situation where she lacked control and could easily find herself out on the street, as she likely did after James Robinson forced her out of their home.

That's likely why she killed her fourth husband. After her marriage to Robinson crumbled, Cotton was introduced to Frederick Cotton by his sister, Margaret. Soon enough, Margaret died of a mysterious gastrointestinal ailment, allowing Mary Ann to get closer to Frederick. They married in September 1870, and Frederick died in December 1871 from the ever-present "gastric fever." As History Collection reports, his wife was paid via yet another life insurance policy and was left with two stepsons.

Meanwhile, Mary Ann had rekindled her old romance with Joseph Nattrass, who had moved nearby. She took him in as a lodger while also starting a relationship with a man she knew as John Quick-Manning. Her stepson, Frederick Jr., and Robert, her infant son with Frederick, died early 1872. Nattrass soon followed, though not before he put Mary Ann down as a beneficiary in his will. As one witness quoted in Mary Ann Cotton put it, Nattrass "died in a fit" and was "in great agony." That left behind Mary, her stepson Charles Cotton, and Mary Ann's 13 child still growing in her womb.

Mary Ann Cotton's children were likely to die by her hand

Few people who lived with Mary Ann Cotton were shown mercy, not least the children who were so unfortunate as to enter her orbit. Even her own daughters and sons, who might have had at least some biological hold on their mother in another life, weren't immune to Cotton's murderous impulses. At the end of her life, as she spoke with officials, Cotton did not offer an explanation for any of her murders. The life insurance policies were clearly a motive.

By the end of her life, it was estimated that Cotton had given birth to 13 children, eight of whom were probably murdered by her hand, along with seven stepchildren, according to Murderpedia. The sheer number of children who met their deaths after coming into contact with the murderess exceeded even the juvenile mortality rate of a dangerous time before pediatricians and obstetricians were available to most people in Britain. According to the Journal of Social History, working class mothers were especially likely to see their own children sicken and die, even if they weren't intentionally causing the illnesses. However, the infant mortality was falling as the century progressed, making Cotton's mishaps all the more striking.

Cotton was caught after the death of her stepson

By May 1872, Mary Ann Cotton had moved to West Auckland with her last remaining child, stepson Charles Cotton. According to The Northern Echo, Mary Ann soon took up with a manager of the West Auckland Brewery, a man by the name of John Quick-Manning. She apparently wanted to give Quick-Manning the dubious honor of becoming husband number five. Mary Ann would also eventually give birth to his child. Yet, the 7-year-old Charles was, to her mind, a serious impediment to her plans.

Female Serial Killers in Social Context reports that Mary Ann's first move was to approach Thomas Riley, a grocer who also happened to be the local assistant manager for the poor relief. She asked him to take the young boy to a workhouse, but Riley refused unless Mary Ann agreed to enter the workhouse too. Mary Ann backed off but not before ominously predicting that Charles would "go like all the rest of the Cotton family." Riley countered that the boy was a "little healthy fellow," but Charles died on July 12, 1872.

Riley grew suspicious and alerted the police. According to the RadioTimes, a local Doctor Kilburn conducted a rushed inquest and determined that the boy had died of gastroenteritis. Yet, he preserved a section of the boy's stomach in a jar. When Riley pushed the doctor, Kilburn re-tested the tissue and found that it was full of arsenic. Mary Ann was quickly arrested.

Mary Ann Cotton gave birth in prison

Mary Ann Cotton's now-inevitable trial was delayed, as it soon became clear to officials that she was pregnant. As The Northern Echo reports, most believe that this child was probably the eighth of her biological children and one of only a few who would survive an encounter with their mother. She named her Margaret Edith Quick-Manning Cotton, partially to target her latest lover as the father of the child. That man was recorded as "John Quick-Manning," though it's possible that he gave Mary Ann a partially false name. It appears that, sometime around the birth, he fled town, with some reports indicating that he went so far as to leave the country, while others claim that he reconciled with his wife and lived a relatively quiet existence thereafter.

Baby Margaret spent some time with her biological mother in the jail cell, before she was eventually given to her adoptive parents, William and Sarah Edwards, aged about 10 weeks old. As per Find A Grave, she thereafter appeared as "Margaret Edwards" on the 1881 census and later married John Joseph Fletcher in 1890. Margaret, her husband, and their baby daughter Clara moved to the United States in 1893, but she then returned to Durham in 1894 as a young widow. She was, as The Northern Echo reports, remembered after her 1954 death as "intelligent, warm and kind-hearted." Perhaps most tellingly, her children lived to tell the tale.

Mary Ann Cotton was only convicted of one murder

After it became clear that young Charles Cotton had died of arsenic poisoning, authorities gave permission for the exhumation of three more of Mary Ann Cotton's alleged victims, the RadioTimes reports. They included Joseph Nattrass, the lover who had added Mary Ann to his will, along with her son Robert and stepson Frederick Cotton, Jr. Nattrass' remains showed that he, too, had been poisoned.

Mary Ann was subject to two court hearings, separated by a period of time set aside for her to give birth to her final child. The first focused on Charles' death and took place in August of 1872. The second, which took place in February 1873, was to center on the deaths of Nattrass, along with those of Robert and Frederick. However, the first hearing led to Mary Ann's conviction for the death of Charles in March of that year. As she was sentenced to hang, the second hearing fizzled out.

As Mary Ann Cotton, Dark Angel reported, Mary Ann blamed lax pharmacists for her young stepson's death. She had meant only to buy harmless arrowroot powder for the ill boy, but a terrible mix-up had occurred, and she was given arsenic instead. A court-appointed lawyer put forth the idea that Charles had ingested arsenic through wallpaper, says the RadioTimes. However, the levels of arsenic discovered in Charles' remains were too high to pin it on the wallpaper. Regardless of her counterarguments, Mary Ann was still to die.

Mary Ann Cotton's execution was a painful mess

After her sentencing, Mary Ann Cotton attempted to save herself through various means, from hoping for a pardon to appear to arguing that everyone else in her life had failed her. She had even, according to Murderpedia, written to her third husband, James Robinson, saying, "if you have one spark of kindness in you — get my life spared ... I must tell you: you are the cause of all my trouble." Robinson refused to meet with his estranged wife in person, though he sent his brother-in-law. Cotton asked the man to circulate a petition in yet another attempt to save her, which did happen, yet it had no real effect on her ultimate fate.

As per History Collection, Cotton was hanged at Durham County Gaol on March 24, 1873. What should have been a relatively quick end turned into a bungle. Someone had either inadvertently or, as some suspect, intentionally miscalculated the drop needed to break her neck and bring death instantaneously. Instead, Cotton dropped only two feet and proceeded to choke, still alive. The executioner reportedly had to push down on her shoulders to speed up the process, which took three minutes to finally kill her.

Mary Ann Cotton lives on as a notorious legend

Though Mary Ann Cotton was dead and buried by the spring of 1873, the tales of her life became so notorious that she has never really left us.

Shortly after her demise, according to The Invention of Murder, Cotton's exploits were used by the Victorians in all manner or moralistic and lurid attractions. A nearby exhibition purported to have a model of Cotton at a coal mine in county Durham, and it's very possible that other cheap "penny shows" would have drawn upon her tale to lure in visitors and their money.

There was also a stage show, The Life and Death of Mary Ann Cotton, that premiered in West Hartlepool not too soon after the real Cotton's execution. The "great moral drama," as it was described, likely used the bloody true crime tropes so beloved by Victorians to impart a decidedly un-subtle lesson about how to live one's life the right way. One of the more chilling legacies of Cotton's time on Earth is a children's nursery rhyme. It includes lines like "Mary Ann Cotton is tied up with string./Where, where?/Up in the air."

Lest you think that works about Cotton fizzled out after the 19th century, look to the myriad of true crime books and drama that still focus on her. According to PBS, there's even been a modern two-part television drama, Dark Angel, which premiered on PBS' Masterpiece Theater in 2017.