The Untold Truth Of The Women Who Ruled Ancient Egypt

When considering the pharaohs of ancient Egypt, who do you imagine? Probably a man, right? He's wearing a crown of some sort, sporting some nice eyeliner, and generally lording it over everyone as a god on Earth. But, what about the goddesses?

Turns out, there were a fair number of women who ruled over ancient Egypt, from its very beginnings to the final dynastic pharaoh on the throne at the time of the Roman takeover. That may be in part because, compared to other societies at the time, ancient Egyptian women were pretty liberated. According to the University of Chicago Libraries, they could enter into contracts, own property, initiate divorces, and generally operate like a responsible, independent adult. Far better than, say, ancient Greek society, which often treated women as baby-rearing machines and little else (via Ancient History Encyclopedia).

Though women in ancient Egypt had many more rights than their counterparts in other ancient cultures, the truth is that Egypt was still firmly ensconced in patriarchy, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia. People expected the pharaoh to be male, while other high-powered positions like those of general, engineer, scribe, and more were dominated by men. Women, meanwhile, were generally expected to take care of the home and children

However, exceptions were sometimes made, especially for upper-class and royal women. In fact, some high-ranking ladies made it all the way to the very top of Egyptian society. Here's the untold truth of the women who ruled ancient Egypt.

Neithhotep ruled ancient Egypt after her husband's death

Since Neithhotep lived in the Early Dynastic Period, which ran from 3150 to 2613 B.C.E., information about her is scanty, much like it is for anyone in that far-away time. However, there are tantalizing clues that she may have ruled on her own after the death of the pharaoh.

Who, exactly, that pharaoh was is still in question. According to When Women Ruled the World, Neithhotep's presumed husband was either the legendary first pharaoh of a united Egypt, Narmer, or one of his close successors, Aha. Whoever he was, this early pharaoh died while his heir was still a young boy, leaving Neithhotep to reign as regent until the new king came of age.

As the Ancient History Encyclopedia reports, there's no direct record that says Neithhotep ruled on her own, but the circumstantial evidence of her power is pretty compelling. The people who uncovered her tomb many centuries later were awed by its richness and size, assuming that it must have been meant for Narmer's kingly successor. Her name has also been included in inscriptions typically meant only for kings. Though Neithhotep remains a mysterious figure from Egypt's deep past, it's pretty clear, given how her name has survived over the centuries since her own time, that Neithhotep was a force to be reckoned with.

Merneith was the true power behind the Egyptian throne

Like many other queens who achieved considerable power in ancient Egypt, Merneith found herself wielding influence because she was both the wife and mother of pharaohs. Though her rule was predicated on her connections to the men in her life, few would have been foolish enough to cross her.

Some of that fear may have come from an early Egyptian practice known as "retainer sacrifice." As When Women Ruled the World reports, some of the first pharaohs were apparently buried with their servants, quite a few of whom appear to have been in good health at the time of their simultaneous deaths, hinting at sacrifice. Merneith would very likely have been the one making the call as to who would accompany the deceased pharaoh.

As per National Geographic, Merneith was recorded as having stepped into power after her husband, King Djet, died. The alternative would have been to allow an uncle to act as regent, but apparently Merneith wasn't fond of letting this male relative manipulate her boy. Perhaps, as When Women Ruled the World argues, Merneith was also looking out for her own skin. It's possible that, if she hadn't taken the reins of power fast, she would have been sacrificed right along with the servants.

Sobekneferu didn't bother to present as a male pharaoh

Ancient Egypt is generally split up into three major periods that cover the era of pharaonic rule by native Egyptians. According to History, these are the Old Kingdom (2686 – 2181 B.C.E.), the Middle Kingdom (2055 – 1786 B.C.E.), and the New Kingdom (1567 – 1085 B.C.E). Those kingdoms are generally separated by intermediate periods that could bring serious upheaval for Egyptians, including the rule of foreign pharaohs. Those power vacuums, however, allowed at least one woman to take power.

As per Britannica, Sobekneferu was the last ruler of the 12th Dynasty, which capped the Middle Kingdom. She came to the throne after the deaths of her father and brother. With no male heirs to take over, Sobekneferu stepped in around 1760 B.C.E., ruling for about four years.

While other female pharaohs, like Hatshepsut, often depicted themselves as male to shore up their claims to power, Sobekneferu consistently presented herself as a woman. Yet, there were still some procedural speed bumps. Silent Images explains that, when a king was crowned, he was referred to by titles that linked him to male gods. Sobekneferu couldn't find equivalent goddesses, meaning that she had to make up a "female Horus" for her coronation.

Ahhotep I commanded ancient Egyptian troops

Though she was the mother of a pharaoh, Ahhotep I didn't concern herself only with domestic duties. She served as a powerful high priestess and is recorded as having put down a dangerous rebellion while her son was out of the country. Seemingly all in the job description for a powerful royal woman of Egypt's New Kingdom.

Ahhotep I, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, lived around 1570 – 1530 B.C.E. She was the mother of Ahmose I, who was an adult with power of his own. Yet, the king couldn't be everywhere at once. While Ahmose was off on a military campaign, a group of foreign people known as the Hyksos began to cause trouble. People who sympathized with this group attempted a rebellion while Ahmose was out of town, but Ahhotep stepped in. Without bothering to consult her faraway son, she commanded the military and seems to have put down the rebellion with little trouble.

When she wasn't running the kingdom in the absence of Ahmose I, Ahhotep I was also fulfilling an important religious role for Egypt. She was the God's Wife of Amun, an admittedly ceremonial priestess title at the time she held it. Eventually, she passed it on to her daughter-in-law, Ahmose-Nefertari, who turned the job into a very powerful office. The University of Chicago reports that, after Ahhotep's tenure, God's Wives of Amun soon wielded considerable political power.

Twosret had a short time on ancient Egypt's throne

Twosret reigned for up to three years, though Google Arts and Culture notes that, since she took on the reign of her predecessor and added his years to her own count, things can get confusing. In fact, everything might have been confusing at the moment Twosret took over.

She gained the throne in a chaotic time following the sudden death of the previous pharaoh, Siptah. Daughters of Isis says that she was likely a co-ruler to Siptah, perhaps explaining the confusion over her regnal years. Frustratingly enough, there isn't a whole lot of evidence that tells us what it was like to live under her rule, though her name pops up in some pretty far-flung inscriptions in places like the Sinai and Palestine.

Though it's not entirely clear if Twosret's reign ended with her natural death or something more sinister — it was a time of great upheaval, after all, and she wouldn't have been the first pharaoh to meet an untimely end — her tomb does offer some interesting information. As Tausret reports, her final resting place is one of the biggest tombs in the Valley of the Kings, a royal funerary complex near Thebes. Since she was one of only a very few women to make it to the valley, it's easy to think that she was taken seriously even in death. According to Britannica, Pharaoh's wives, meanwhile, were usually consigned to the Valley of the Queens.

Nefertari lived at the pinnacle of ancient Egypt

Ramesses II, also known as "Ramesses the Great," is perhaps one of the first known ancient rulers to really, really enjoy looking at himself. As the BBC reports, he is one of the most prolific monument builders of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs. Those monuments, naturally, included many statues, paintings, and carvings of Ramesses, not to mention inscriptions that, frankly, make him seem too good to be true.

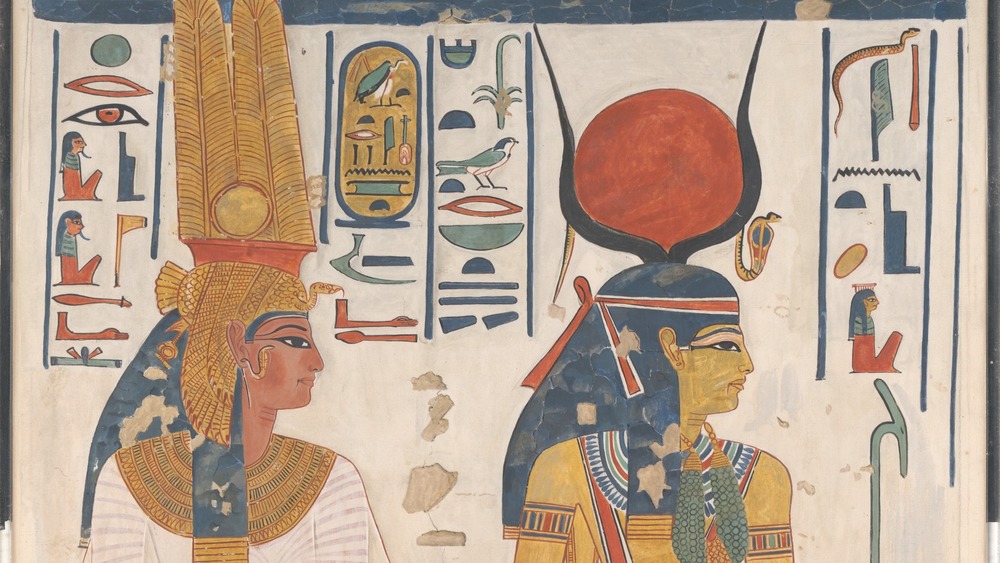

The fact that his favorite queen, Nefertari, also appears on quite a few of these monuments speaks to her power and influence, especially in the face of her husband's rampant ego. Still, according to PBS, there isn't much direct information about Nefertari, so historians are stuck trying to glean information from things like statues and her lavish tomb. Her burial spot, in the Valley of the Queens, was looted after her death, though robbers weren't able to take the gorgeous paintings and carvings off the walls.

After her death, Ramesses also built two temples at Abu Simbel, with the smallest, naturally enough, dedicated to her. Though the statues of Nefertari there aren't quite as big as those of her husband, the fact that someone as apparently self-interested as Ramesses was compelled to respect her in these ways hints that she was an especially powerful royal woman with a lot of sway with the king.

Nitocris may have been the first woman to rule Egypt alone

For a long time, Nitocris was dismissed as nothing more than an ancient tale. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, she was long thought to be the creation of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century B.C.E. and didn't appear to always be concerned about piddling matters like historical accuracy or fact checking.

Nitocris is mentioned by a couple of other Greek sources, though she doesn't appear in any native Egyptian texts. Some sources state that she must be real, since she appears on a list of kings known as the "Royal Canon of Turin." Yet, as A Companion to Ancient Egypt notes, that name appears at the end of a fragment. It could very well be that her mention is a jumbled-up tag of parchment that actually refers to a male king. Sounds like, if nothing else, mentioning Nitocris at an Egyptology conference is a surefire way to start a heated argument.

If she did exist, however, she had a fearsome reputation. Herodotus wrote that she took the throne after the assassination of her own brother. Nitocris built a grand underground chamber and invited the murderers to a grand feast. She then released the waters of the Nile into the chamber, drowning the men and securing her revenge.

Tiye wasn't just the pharaoh's mom

There's no mistaking the fact that Queen Tiye was a major part of her husband's prosperous reign. Later, when her son, the pharaoh Akhenaten, upended much of Egyptian belief and culture to install his revolutionary monotheistic beliefs in the kingdom, Tiye remained a vital political figure from the old regime.

Unlike many of the other women who ruled Egypt, Tiye's influence is well-documented thanks to the Amarna Letters. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art reports, these were clay tablets inscribed with Akkadian cuneiform, found at Akhenaten's capital. Most of the tablets are from foreign rulers north of Egypt. As per the Ancient History Encyclopedia, the content of these letters also show that Tiye was a well-regarded political mover and shaker alongside her male relatives.

Tiye also shows up in plenty of monuments via paintings and statues. Notably, her statues are often as large as those of her husband, Amenhotep III. Typically, a king's image showed him as larger than others around him as a way of visually showing his high status. This means that Tiye's same-size depictions point towards her influence. Her name also shows up in inscriptions enclosed in a special sign called a cartouche, generally only reserved for kings. More obviously, as the Ancient History Encyclopedia notes, is the evidence that she corresponded directly with foreign rulers like a kind of ancient secretary of state during the reign of her son.

Hatshepsut left a serious mark on ancient Egyptian history

Not only does Hatshepsut's 21-year reign appear to be long even for male pharaohs, but she also undertook a campaign of expeditions and monument building that secured her legacy, even when it came up against her rather sour-grapes successor.

Like other women rulers before and after her, Hatshepsut's ascension hinged on her male relatives. According to History, the 12-year-old Hatshepsut married her half-brother, Thutmose II, setting her up to become queen one day. When Thutmose II died, his son by another wife became king. Yet, the young Thutmose III was only a boy. Someone would have to act as regent until he came of age. Hatshepsut was conveniently available.

That's not so strange, since other women had acted as regents. Yet, Hatshepsut's next move was shocking. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, she decided that things would work better if she were co-ruler. Hatshepsut eventually began presenting herself as a legitimate ruler, to the point where some statues and inscriptions show her as a male king, complete with flat chest and a ceremonial false beard. Besides her extensive monument building, Hatshepsut also pushed for a now-legendary expedition south to the land of Punt, likely on the coast of what's now Eritrea. Egyptian delegates returned with rich, exotic goods. One inscription claims that "never were such things brought to any king since the world was."

Nefertiti may have reigned on her own

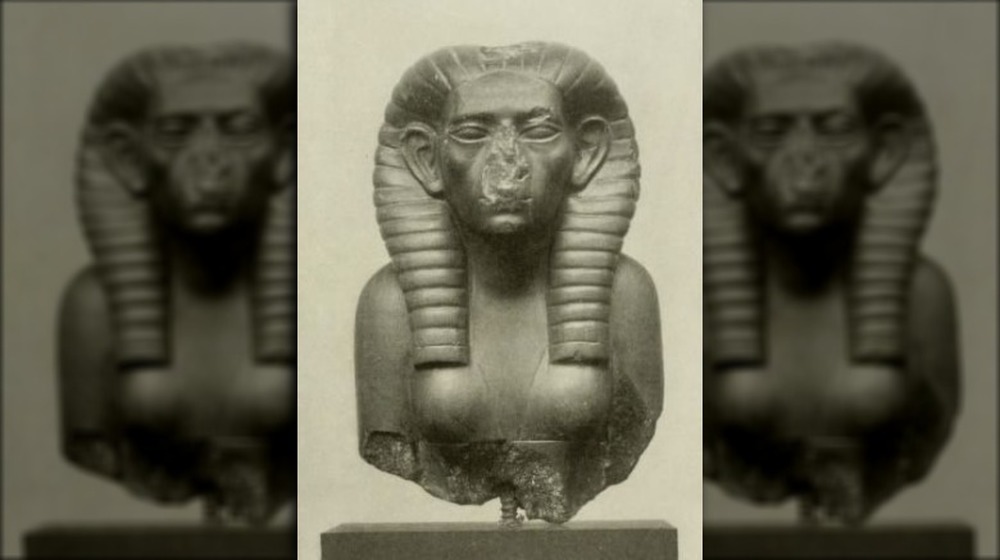

Perhaps one of the most famous images of ancient Egypt is that of the bust of Nefertiti, queen of Egypt. Now housed in Berlin's Neues Museum, the sculpture first saw the modern era when it was uncovered in 1913 in the ruins of Amarna, the abandoned capital of pharaoh Akhenaten (via History). Since it's gone on display, the bust has struck people with its stunning beauty.

Yet, the queen who was the subject of this famous sculpture was more than a pretty face. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, she was the wife of Akhenaten, the notorious heretic pharaoh of Egypt's New Kingdom. Shortly after he took the throne around 1353 B.C.E., Akhenaten demanded that the kingdom switch to the monotheistic worship of the sun god, Aten. He uprooted the court and moved it to a newly constructed city, Amarna, where he was accompanied by Nefertiti.

Nefertiti is shown alongside her pharaoh husband more than any other queen before her, History says. She's also shown in active roles, from leading worship of the Aten to smiting enemies of the state. Some scholars suspect that she may have even reigned on her own, perhaps first surfacing as Akhenaten's co-regent, Neferneferuaten. Whatever really happened, there's no doubt that she was a uniquely powerful Egyptian queen.

Arsinoe IV proved just as dangerous as male pharaohs

According to the Dangerous Women Project, Arsinoe IV was one of five children of Ptolemy XII, a rather unpopular pharaoh of the Ptolemaic dynasty. He was so unpopular that one of his children, Berenice, attempted to oust him and even ruled on her own for a short time. According to Doomed Queens, Berenice met her untimely end via execution in 55 B.C.E., after her father's three-year absence.

The Ptolemys were, clearly, a pretty ruthless family. In 48 B.C.E., as per the Dangerous Women Project, Ptolemy XIII was co-ruler of Egypt with his sister, Cleopatra VII. Young Ptolemy didn't want the competition, however, and kicked Cleopatra out. The two siblings began to war against one another, leaving an opportunity open for Arsinoe to set herself up as a pharaoh. She eventually teamed up with Ptolemy XIII against Cleopatra, but their elder sister had an even bigger ally — Julius Caesar. Eventually, Ptolemy XIII was killed, while Arsinoe made it through Roman captivity to see her own sister take up with Mark Antony. Yet, Cleopatra still saw Arsinoe, who was being addressed as "queen" again by some Egyptians, as a threat. She had Arsinoe assassinated, as the younger ruler and her supporters still posed a serious threat to Cleopatra.

Cleopatra VII was the last of the pharaohs

Though she's often been depicted as a femme fatale, the truth was that Cleopatra VII was far more intelligent and canny than some ancient scheming vixen.

As Smithsonian Magazine reports, Cleopatra was driven from Egypt by her brother-husband, Ptolemy XIII, in 49 B.C.E. Roman general and eventual emperor Julius Caesar eventually got involved, though the younger Ptolemy forbade his sister from entering the capital of Alexandria for a peace conference. Cleopatra reportedly snuck in anyway and so impressed Caesar that he backed her claim to the throne and fathered a son, Caesarion, with the queen. To ensure her survival and the claim of her son to the throne after the death of Ptolemy XIII, Cleopatra had yet another brother, Ptolemy XIV, killed.

The Roman government got pretty nervous about Cleopatra's insinuation into the political and private life of the empire. She consistently proved herself to be a shrewd manipulator of political relationships and her own self-image, often presenting a glamorous, powerful persona in order to draw even more support in the midst of dramatic upheaval. After the assassination of Caesar, ThoughtCo reports, Cleopatra used those tactics to establish Caesarion as the next ruler and to set up her own relationship with Roman politician Marc Antony. Though Roman forces eventually turned against the pair, and Cleopatra and Antony both are said to have committed suicide, her legacy as the last dynastic pharoah of Egypt remains strong.