What It Was Really Like Being A Grave Robber

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Life was rough in Victorian times, and a good job was hard to come by as industrialization marched on. The demand for cadavers, on the other hand, was a nefariously booming business. Robbing graves became a popular hustle from the 17th to 19th centuries. Doctors were on the hunt for cadavers to experiment with surgical procedures and to become more acquainted with human anatomy. On top of that, the wealthy were often buried with family heirlooms, and robbers also targeted archaeological sites in Egypt.

It wasn't easy work, as many targeted grave sites were on private, historical, and even ancient land. Eventually, grave robbers, or "resurrectionists," had to jump through more complicated hurdles as society caught on to their game, sometimes even leading them to graduate to murder as a means of body procurement. The appeal of robbing graves for medical professionals was the hefty paycheck, while others were in it for valuable vintage jewels or ancient artifacts to sell to antique dealers. Did we mention that grave robbing wasn't even illegal until the 1830s?

In the golden age of grave robbery, one man's body was another man's bread and butter.

Body snatching for an easy buck ... and science

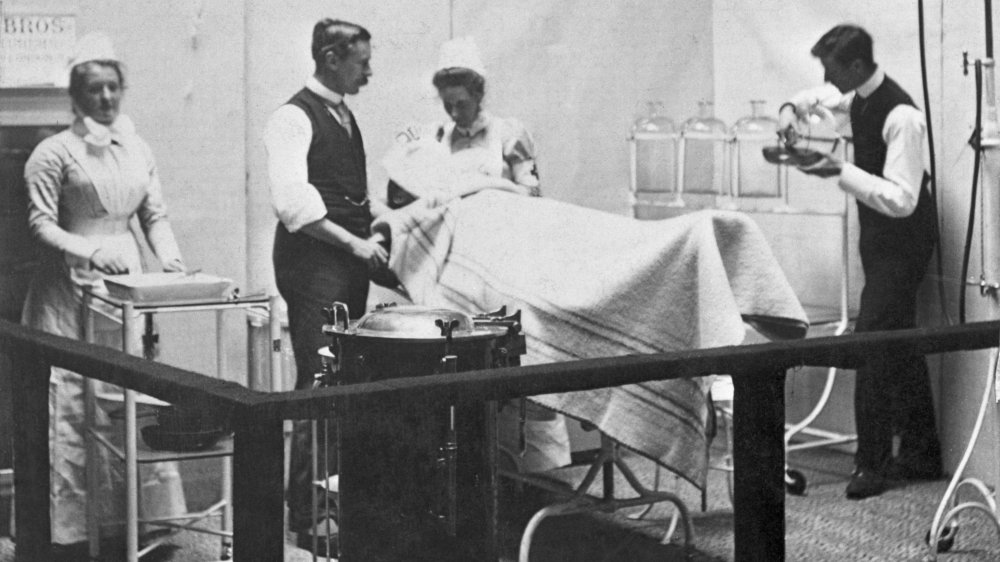

Body snatching grew popular once science and medicine became a more pronounced fixture in society. Medical schools would pay contractors to dig up cadavers for educational purposes. The recipients wouldn't ask questions about where the body came from, and they would sometimes remove identifying features of the body, such as the scalp, ears, or eyes, immediately after delivery just in case the authorities came knocking.

Due to a reduction in executions by the late 17th century, which was the traditional source of cadavers, the grave robbing business began to boom. According to PBS, medical facilities were in great need of fresh bodies due to poor refrigeration methods. The practice, while deemed unethical today for obvious reasons, was seen as a necessary evil to the medical community in order for the general public to benefit from anatomical expertise and eventual surgical procedures that would save countless lives.

There were no laws to prevent such acts until the 1830s. And even after such time, the act of grave robbing was considered a misdemeanor and rarely prosecuted. Lawyers argued that since there was technically no victim, there was no crime. And many cemeteries were in cahoots with the resurrectionists.

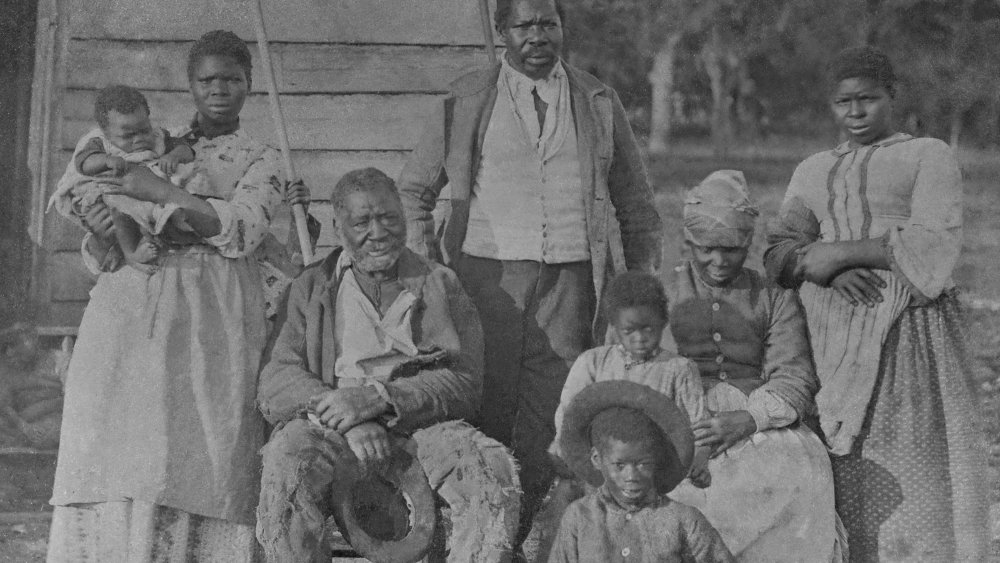

Grave robbers disproportionately dug up the bodies of African Americans

Grave robbers were often pointed toward where to find cadavers. In the United States, medical schools often turned to burial grounds in poor and marginalized parts of town. A majority of the snatched bodies were, unfortunately, of enslaved and freed African Americans.

The families of the unfortunate deceased victims were not fans of people snatching corpses without consequence, but despite several "resurrection" riots from the late 18th century to the mid-19th century, the practice widely continued, and authorities turned a blind eye to the most powerless and disenfranchised factions of society. When slaves passed away, usually due to disease or overwork, they were often buried unmarked within a mass patch of land. While the wealthy could protect their loved ones' gravesites, the Black population could not afford the luxury. New York City's Columbia College and New York Hospital were especially known for procuring cadavers from Manhattan's "Negroes Burying Ground," despite petitions from the African American community.

It is worth acknowledging, therefore, that the medical knowledge and advancement within the last four centuries was widely obtained by robbing the graves of African Americans. "For far too long, their loss was unremembered and unmourned," writes archaeologist James M. Davidson in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology. "Through all of this a complete destruction of identity and dignity was achieved, rendered possible through casual racism, and all in the name of science."

Mortsafes and preventing grave robbery

Sometimes grave robbers weren't after bodies but the treasure or artifacts buried alongside them. Word got around town when someone from a rich or famous family was buried. Eventually, people would attempt to prevent postmortem thievery by installing mortsafes over the graves.

The first mortsafe dates back to around 1816. There were a variety of models, but all were considerably heavy in order to protect the grave. A complex of iron rods and plates dug into the earth and topped aboveground with stone or iron, mortsafes were only affordable to the upper echelons of society. The gravesites were effectively caged and double-sealed to ensure that thieves could find no way to extract the deceased. As noted by the Wellcome Collection, some fixtures were temporarily rented for a few weeks, just long enough to keep the robbers at bay until the body grew putrid (and useless for anatomical purposes). Others were constructed for permanent use.

Over the years, most mortsafes have been discarded or recycled. Some relics can still be spotted, however, in gravesites throughout the Western world, particularly in Scotland.

Tomb raiders and the search for buried treasure

Ancient Egyptian tombs have been raided for centuries and still get robbed today, with the illegal antiquities trade continuing to boom. Egyptians could bury their dead with an entire household's worth of possessions, and the tombs were sometimes robbed before they were even sealed.

According to Ancient Egypt Online, tomb robbers were often tradesmen who would hide treasures in their equipment and carry them away, sometimes working in groups to plunder a site. The ancient Egyptians were wise to the idea of tomb raiding, and, for example, created a simple yet elaborate system of blocks and grooves within the Great Pyramid of Giza to protect the King's Chamber. Unfortunately, the site has since been breached by numerous thieves.

While tomb robbers tend to sell their finds to antiquities dealers, often inadvertently preserving important relics of history in the process, a very gray area remains. Dealers aren't exactly fooling themselves. They realize their trade encourages looting and other unlawful behavior. A steady increase in U.S. and foreign legislation threatens the future of the antiquities business, but there are also some safeguards in the works. Collecting and scholarly communities are banding together to create a global registry of legitimate archaeological antiquities, which would serve as a powerful tool against looting.

Grave robbers held dead bodies for ransom

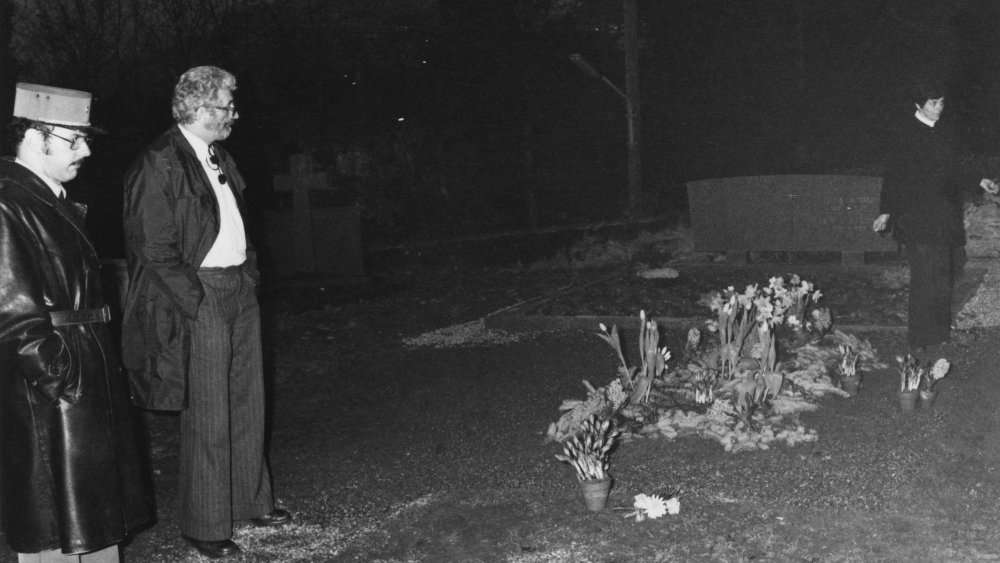

Charlie Chaplin and Abraham Lincoln have more in common than being famous historical figures. Both of their bodies were dug up and held for ransom by grave robbers, who held their remains for ransom hoping to make a mint.

Silent film star Chaplin died on Christmas 1977. According to Mental Floss, in March 1978, a pair of thieves unearthed his 300-pound oak coffin in Switzerland. They followed that up by calling Chaplin's widow, Oona, and requesting the equivalent of $600,000 in cash for the body. Oona refused the offer, however, stating, "Charlie would have thought it rather ridiculous." The men were eventually apprehended by police and charged.

More than a decade after President Lincoln was assassinated, everyone from thieves to politicians wanted a literal piece of him. Per Gizmodo, on November 7, 1876, a band of counterfeiters tried to exhume his cadaver and hold it for ransom from the U.S. government for a whopping $200,000 (equal to over $4 million today), as well as the release of a fellow counterfeiter from prison. The robbers managed to saw through the tomb's padlock, but the marble lid was too heavy to lift. Secret Service members showed up before long, and Lincoln and his family now reside in a practically impenetrable tomb.

Nighthawking: modern-day grave robbing

Nighthawking, which is the illegal metal detection of objects from beneath the ground in darkness, is usually attempted at official archaeological sites or on private historical land. Many historical artifacts have been stolen from excavation sites, and nighthawking happens to this day. All thieves need is a shovel, a metal detector, and a spade. And as metal-detecting equipment becomes more affordable and available, more people are doing it.

One famous case of nighthawking happened in the UK in 2015, when two men found 300 Viking coins, a ninth-century gold ring, a dragon's head bracelet, and a crystal rock pendant on private land belonging to Lord Cawley of Leominster, as detailed by The Guardian. The thieves sold their treasure on the black market but were jailed four years later. In the UK alone, a total of 240 sites have been reportedly "nighthawked" between 1995 and 2008, 88 of which were Scheduled Monuments.

Grave robbers were emboldened by a pair of Hare-raising resurrectionists

William Burke and William Hare became known for their grave robbing exploits in the late 1820s, when they began delivering bodies to a doctor who became so desperate for more that the pair of men went on a killing spree in Edinburgh, Scotland. Prior to their headline-worthy escapades, grave robbers tended to wait until a person was dead before profiting off their body. Burke and Hare would soon become the most infamous body snatchers in history and have been the subject of various films.

Their first exploit was selling the body of a dead lodger to a desperate doctor working at Edinburgh Medical College. But the doctor wasn't happy with just one. Per The Lineup, Burke and Hare would ultimately murder 17 lodgers, sex workers, and other unfortunate souls. Due to their success, Burke started to become overconfident. On Halloween night in 1828, he killed a woman but was too drunk to deliver her body and was caught the next day.

At the trial, Hare testified against Burke before fleeing to England. Burke was hanged and publicly dissected at the very medical college he used to supply bodies to. Lore states that the anatomist who performed the dissection dipped his quill pen into Burke's blood.

Burke and Hare inspired a gang of grave robbers

A notorious gang of resurrectionists, who were said to have been inspired by Burke and Hare, would become known throughout London for their morbid black market dealings.

The group was composed of John Bishop, Thomas Williams, Michael Shields, and James May. The London Burkers had a modus operandi: They would sneak into burial grounds at night, strip dead bodies, and package them to a storage spot by horse and cart or even on their backs in sacks and baskets. The gang would utilize different parts of the corpse, like the teeth, which they would sell to dentists.

But when snatching fresh corpses became too risky, they started to follow in Burke and Hare's footsteps by creating their own bodies. According to East London History, one of the anatomists who was receiving corpses from the men eventually caught on to their murderous activities, and two of the four London Burkers were found guilty of murder and executed in 1831.

Bishop and Williams confessed to the murders of a ten-year-old boy, a 14-year-old agricultural worker, and a 35-year-old woman. They also admitted to modeling their crimes after Burke and Hare. Bishop proudly fessed up to selling up to 1,000 bodies to medical professionals. His crimes even inspired novelist Charles Dickens to focus on the hard-knock lives of young beggar boys in London, particularly in The Pickwick Papers.

A grave robber's technique

When it came to professional body snatching, there was a method to the madness. Robbers would work in teams and usually dig up the body within a day after burial.

By eliminating the need to dig up the entire coffin, the crime could go undetected for a longer period of time. Instead, according to CemeteryIndex.com, body thieves would uncover the head end of the grave and then hoist the body to the surface with rope or a metal hook. Then they'd cover their tracks by moving the soil back on top of the scene of the crime.

The grave robbers would leave clothing and jewelry behind, however, as stealing these items could be considered a felony. Believe it or not, body snatching was merely a misdemeanor. It was also common for grave robbers to hire women to help them claim bodies by identifying them at poorhouses. The women would also hang around funerals to gain intel on soon-to-be corpse victims.

How much did grave robbers get paid?

Grave robbing was quite lucrative after the American Revolution and continued to be during the Victorian era, as many doctors and medical centers had funds they would use to pay freelancers when they became desperate for cadavers so they could develop and perfect their surgical methods.

In order to be employed as a grave robber, there were two main criteria: You had to be strong enough to dig six or more feet down into the grave and haul out a dead body — or sometimes the whole coffin. You also had to have a stomach of steel, as the smell of decay and the very sight of the corpses were truly morbid and unpleasant things. Per All That's Interesting, one body could earn between $5 and $25 (in a time when well-paid workers pulled in $20 to $25 per week). The amount depended greatly on how newly dead the body was. The fresher the body, the better it paid.

If you think grave robbing sounds like a hard way to make a living, it wasn't even the worst trade in its day. Other Victorian gigs included collecting dog poop, tanning hides, hunting for treasure in sewers, and leech collecting. So delivering bodies to hospitals definitely beat an hourly wage for shoveling canine excrement.

Future grave robbers started a club at Harvard

A group of Harvard students formed a secret society around 1770 called the Spunker Club, but it was never officially recognized by the university. Maybe that's due to the fact that its members snatched corpses from coffins. It was so secret, in fact, that members were forbidden to write the club's name, according to History.

Harvard University student John Collins Warren and a few men crept into Boston's North Burying Ground one late night in 1796. Their motive was to snag the freshest corpse who also conveniently happened to have no kin. Stuffing the unfortunate corpse into a bag, they took it back to Harvard's campus. John's father, Dr. John Warren, was a Harvard anatomy professor and soon learned about his son's misdeed. Instead of punishing him, however, he praised his work. Apparently, dear old dad was also a body snatcher in his day.

The Spunker Club consisted mainly of medical students but also some morbidly curious bystanders. The club even included the only surviving son of the famous patriot Samuel Adams, as well as a future secretary of war, William Eustis.

Grave robbing became illegal in 1832

Grave robbing would eventually become officially illegal thanks to various governments. According to The Public Domain Review, the trials of Burke and Hare and the London Burkers ultimately led to the passing of the 1832 Anatomy Act, followed by New York outlawing grave robbing in 1854. Massachusetts was technically ahead of the curve, passing their own version of an Anatomy Act in 1831.

The Anatomy Act, which originated in Britain, did not deem the taking of corpses from graves illegal in itself, as the corpse had no legal standing and was not owned by anyone. Instead, the illegal act was the dissection of the corpses and the theft of items other than the corpse itself. During the parliamentary debate of whether to pass the Anatomy Act, one of the biggest arguments for legislating body snatching was based on the fact that neither the body's relatives, nor the body, were consenting for it to be used for medical purposes.

Unfortunately, the law did little to stop ambitious and aspiring grave robbers and tomb raiders.