St Anthony's Fire: The Tragic Illness That Plagued History

Humans, it turns out, are pretty gross. Wherever mankind goes, they bring along a lot of disease. And when it comes to spreading it? They're pretty good at that, too. History is filled with plagues and pandemics, and here's the thing — usually they come with a general sort of laundry list of symptoms. Typical ones include things like some sort of gastrointestinal distress, some version of rashes or other skin conditions, and the hurried evacuation of all bodily fluids. It's horrible, but sadly pretty typical of these sorts of plagues.

But scattered throughout history are instances of an illness that brought something else as one of the major symptoms: Mass hallucinations. The hallucinations were so powerful that some people needed to be chained down to keep them from killing themselves in an attempt to get away, and it's really no wonder that for a long time, it was thought to be a sign that a person was being visited by divine retribution — that's some serious Old Testament, fire-and-brimstone sort of wrath right there.

It was widely known as St. Anthony's Fire, and (spoiler alert) it had a very earthly origin. That doesn't really make it any less terrifying, though, so let's talk about the little-known illness that took countless lives in a pretty horrible way.

The first documented instances of St. Anthony's Fire

When the illness was first recorded in detail, it was called ignis sacer (or, "holy fire,") and according to Lapham's Quarterly, that first in-depth mention came way back in 994. (For some context, this was the time in history when the Vikings were still a major European powerhouse on the "raiding and trading" scene.) French historian François Eudes de Mézeray wrote on the "plague of invisible fire" that burned across the southern part of his country, leaving as many as 40,000 dead and dying in its wake. As if that's not eerie enough, there are historical records that suggest this outbreak was the second time the area had been devastated: in 944, around 20,000 people in Aquitaine — nearly half the area's entire population — had died from it.

It's difficult to say how many times this holy fire rained down on communities across Europe, but Hyperallergic says that there are around 40 accounts of major outbreaks. And they're huge: Just one 1418 incident in Paris killed an estimated 50,000 people.

It's been happening for a long time. University of Pittsburgh's Paul L. Schiff, Jr., PhD., says (via the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education) that the earliest mention of the effects of the substance later found to cause this holy fire — a fungus called ergot — have been found in texts dating back to China in 1100 BC. It was also mentioned on ancient Assyrian tablets, in the papyruses of ancient Egypt, and in a few books of the Bible.

What were the symptoms of St. Anthony's Fire?

When the so-called "holy fire" swept across an area, it brought with it some deadly symptoms that are nothing short of terrifying. The University of Pittsburgh's Paul L. Schiff, Jr., PhD., says (via the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education) that there were two different forms the disease would take, and one is known as "the convulsive form." That version — which was often seen in Germany — included things like muscle spasms, convulsions, and rigidity in the arms and legs, along with hallucinations, delirium, and life-threatening diarrhea.

That's terrible, but one might argue that the other version — the "gangrenous form" — was even worse. That's the kind that happened more in France, and it started with a swelling in the hands and feet — sometimes, along the entirety of a person's arms and legs. That came along with a burning sensation that gave rise to the condition's fiery names, and it would only get worse. Blood flow to the extremities would stop, and Schiff says it "ultimately culminated in the separation of a dry, gangrenous limb at a joint, without pain or loss of blood."

Take a minute to imagine this: tens of thousands of people woke up one morning to swelling and a burning sensation, only to have their hands and feet gradually turn black and just sort of... fall off. That's the sort of thing that shows up in nightmares.

Let's talk about those hallucinations that went along with St. Anthony's Fire

The idea of blackened hands and feet that just kind of fall off probably overshadowed another symptom: hallucinations. These, too, were no laughing matter. According to Hyperallergic, sufferers weren't besieged by just any random kind of hallucination, but by a very particular kind linked to what they were physically experiencing. The burning sensation in the extremities helped make visions of being burned alive, or being engulfed in flames, seem very, very real — and it's also why many believed it was the manifestation of some divine punishment.

It was rumored that the illness was an early warning sign that someone was beginning their descent into hell, and for the devout and the faithful, that had to have only added to the agony. Lapham's Quarterly says many accounts describe images of being covered with bugs, harassed by demons, or tormented by twisted, evil animals.

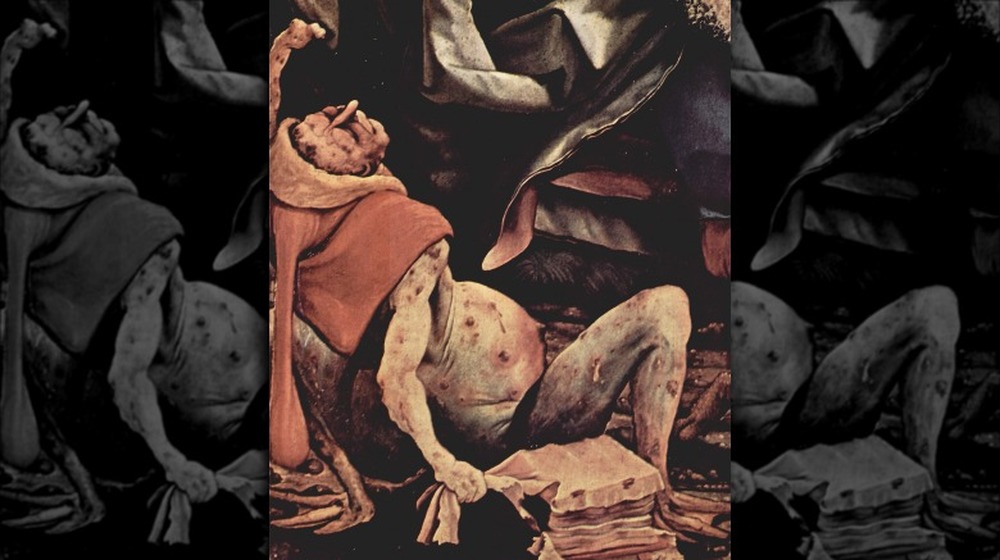

It's been suggested that St. Anthony's Fire and the fire-and-brimstone hallucinations that went along with it were the inspiration for countless Renaissance painters who used canvas to recreate the torment sufferers felt, similar to St. Anthony's torment in the piece pictured.

How did St. Anthony get involved with this holy fire?

The illness was popularly called St. Anthony's fire, but why? Hyperallergic says the answer is written loud and clear in countless Renaissance paintings that depict the suffering of St. Anthony. (Like the one pictured, by Michelangelo.) The saint we're talking about (and there's a few named St. Anthony) is St. Anthony of Egypt. According to Britannica, he's known as being a hermit, and for having some serious hallucinations.

His earliest followers — Christianity's first monks — were witnesses to what they called his visions. They took a variety of forms: Sometimes, it was a person bringing food to the community who was really the devil in disguise, and sometimes, it was said that demons, devils, or wild animals would descend on Anthony's little flock. Sometimes it was soldiers who beat him, sometimes it was women who tried to tempt him, and every time, he triumphed. The visions that he recounted — and fought — were so much like those suffered by those conflicted with the holy fire that he became firmly associated with it, and countless Renaissance painters even layered his story over that of ordinary people suffering from affliction with the "holy fire" — all tied together by visions.

How do we know it's not just a coincidence? Not only do many depict the winged beasts and demons that many claimed to see, but they also seem to include what we now know is the cause: a stalk of rye contaminated with a fungus.

Order of Hospitallers of St. Anthony

St. Anthony's Fire is also called ergotism, and it was such a widespread problem that in around 1100, followers of St. Anthony organized in Grenoble, France, and dedicated their lives to helping those afflicted with it (via Britannica). They formed the Order of Hospitallers of St. Anthony, and Dr. John Horgan of Concordia University Wisconsin says (via Brewminate) that over the next 300 years, they founded somewhere around 400 separate hospitals solely to care for those with ergotism.

Treatments were heavily steeped in the legend of St. Anthony: There was St. Anthony's water (a topical cream) and St. Anthony's wine, which was made with grapes believed to be bestowed with healing abilities due to their proximity to cathedrals where the saint's relics were kept. Antonites-balsam was, says research from the International Congress Series, a major first: It was the "first transdermal therapeutic system in the history of medicine."

It's also likely that they did have a positive effect for a lot of people, because when they went into the care of the hospitals of the order, they didn't just get food and ointments supposedly blessed by the curative powers of a saint. Wines made by the monks have been found to have pain-relieving properties, and even more importantly, people were transitioned to a diet free of the fungus that had caused their illness in the first place.

So, what was causing these outbreaks in the first place?

It's the elephant in the room: What was causing all of these outbreaks, mass hallucinations, and deaths in the first place? Rye, infested with a fungus called ergot. And here's where things get complicated. According to research done by Paul L. Schiff, PhD., people knew for a long time that there was something different about rye infected with what the ancient Assyrians described as a "noxious pustule" way back in 600 BC. For a long time, it wasn't necessarily thought of as an infection, but "a 'super' rye." That was the case until 1764, when scientists finally classified the strange growths — correctly — as a fungus.

Lapham's Quarterly says that it was common to find the fungus growing on rye in certain areas of Europe, particularly in France and Germany. Grains were harvested, sent to the mill, and ground into seemingly normal flour. That was turned into bread, and anyone unfortunate enough to eat the bread was going to find their lives going downhill very, very quickly.

Even before ergot was recognized as a fungus, it was well-known that eating it caused the so-called St. Anthony's fire. That connection was discovered in 1597 at Marburg University, and about 30 years later, researchers also found that it had the same effect on animals. Still, it kept happening even in spite of legislation put in place to try to stop the use of infected rye.

Ergot is related to a highly controversial substance

The hallucinogenic properties of the rye fungus called ergot were elevated to new heights in 1917. That, says The Atlantic, is when a professor named Arthur Stoll took some ergot and separated out something called aotamine — which might not mean anything now, but it will in a minute.

National Geographic says that ergot "works" by interfering with the circulatory system, and researchers knew that in small, carefully controlled doses, ergot didn't cause hallucinations or the death and droppage-off of hands and feet. Instead, it could be used to do things like stop excessive bleeding after childbirth, which is interestingly one of the precise things that ancient midwives used to use it for.

The isolation of aotamine led to interest in the isolation of other compounds that could have legit medical properties, and along the way, they found the central nucleus of what made up ergot. That was something they called lysergic acid. Chemist Albert Hoffman started sort of sticking other compounds onto this base of lysergic acid, and on his 25th attempt, he used diethylamine, and created LSD. It didn't really seem to do anything interesting at first — and it definitely wasn't medicinal in the way he'd intended — but after he went on his first acid trip in 1943, well, the rest is history.

Ergot and the plagues of dancing

The so-called dancing plagues of Europe are perhaps one of history's strangest footnotes. According to The Lancet, the first incident of mass hysteria characterized by uncontrollable dancing seized 18 people in 1021. It was said they danced for a whole year before regaining control of their bodies, and while that seems unlikely, that's not the only story.

One 1374 outbreak of dancing mania was recorded by numerous writers, who wrote that not only were thousands of people seemingly forced to dance and dance and dance some more by some invisible force, but that countless screamed as they danced: They begged local clerics to save them from the demons that were tormenting them, and from the seas of blood they were drowning in. Other chroniclers wrote of people who danced until their bones broke, or until they simply collapsed and died.

The whole "hallucinating demons" thing should sound very familiar, and that's given rise to the theory that these infamous dancing plagues were ergot-related. It makes sense... but not everyone is convinced. Others suggest it was simply some sort of mass delusion brought on by a combination of acute stress and fear of eternal damnation, while others (via Smithsonian) link it to a disease that causes uncontrollable tremors. Bottom line? No one really knows.

Ergot and the French Revolution

Most people know at least a little about the French Revolution, even if it's just the bit that involved Marie Antionette, a misquote about eating cake, and a lot of guillotining. But it's entirely possible that it wasn't just about things like inequality and starvation: Some have suggested that ergot had a little to do with kick-starting the whole thing.

Mary K. Matossian is a historian at the University of Maryland, and she suggests an outbreak of ergot poisoning was in part responsible for a wave of panic, terror, and violence that rolled through France in the late summer of 1789. The incident was well-known: it's called the Great Fear, and according to History, it was an uprising sparked by the storming of the Bastille. Peasants threw aside their plows, picked up their pitchforks, and started burning. Matossian looked at contemporary accounts and found that in many cases, what people said was happening simply wasn't. She cross-referenced that with the likelihood that the climate and time of year would be right for ergot, and came to the conclusion that there were signs of an outbreak of St. Anthony's Fire.

While not everyone was convinced, she explained it this way to The Washington Post: "I'm not saying ergot is the only reason for the French Revolution. That would be too simplified... But this was a precipitant. It was one of those things that pushed the course of events onto a radical track."

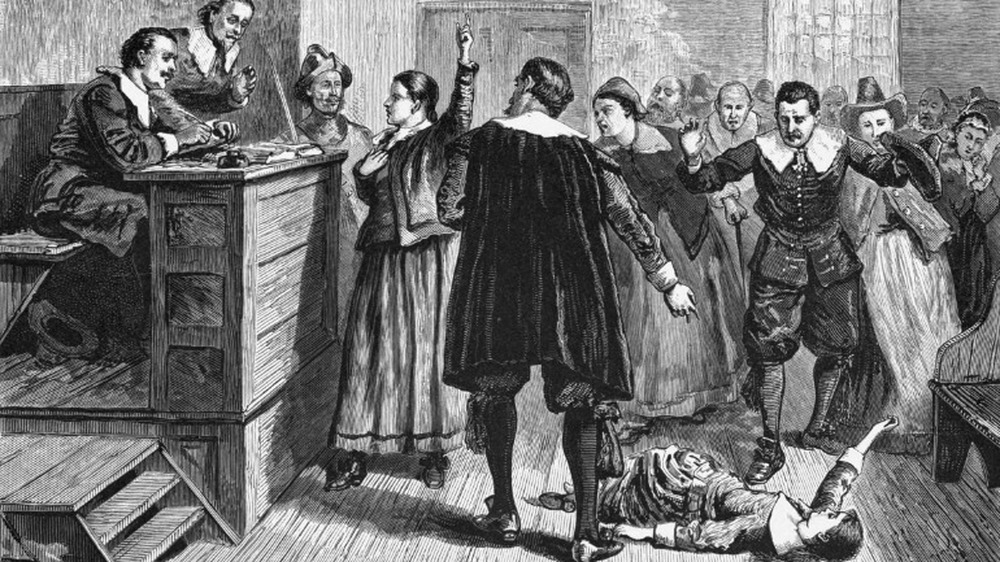

Was holy fire behind the Salem Witch Trials?

The Salem Witch Trials are one of the most notorious events in American history, and in 1976, a behavioral scientist named Linnda Caporael suggested that the girls who accused others in their community of being witches in league with the devil were actually high on ergot. The climate had been right, she argued (via Country Living), and pointed out that it made sense. They had, after all, reported hellish visions, were seized by convulsions, and even suffered skin lesions that could be explained by ergot poisoning.

It kind of makes sense, but Vox says that it's not as widely accepted as it might seem like it should be. Other historians and scholars haven't just disagreed with it, but dismissed it as complete poppycock. Not all of the symptoms fit, the naysayers point out, and those same naysayers condemn it as a highly simplified version of historical events that would have been happening at the time — and provided other motives for the witchcraft accusations.

Harvard Medical School's Alan Woolf came to the conclusion that given the lack of data on weather, crop failures, a lack of residual effects of illness, and other occurrences of witch trials in the mid to late 17th century, "it seems very unlikely that the convenient theory of ergot poisoning is an adequate explanation."

Ergot... or biological warfare?

In 1951, 230 people living in the French village of Pont Saint-Esprit fell victim to a widespread illness right out of the Middle Ages — and it was so awful that one survivor, Leon Armunier, told the BBC that he would choose death before going through it again.

One man tried to drown himself in the nearby river, while onlookers reported he shouted (via Smithsonian), "I am dead and my head is made of copper and I have snakes in my stomach and they are burning me!" Others later said they had been convinced they were being eaten alive by wild animals, while others hallucinated strangers with naked, grinning skulls for heads. One woman hurled herself from a third story window to escape what she thought was a burning building (via Lapham's Quarterly), and Hyperallergic says that another man jumped from his second-story window. He'd believed he was actually an airplane: instead of flying as he'd intended, he broke all the bones in both his legs... then continued to run, until eight other men were able to catch and subdue him.

Ergot was confirmed to be the culprit in autopsies done on those who died, and both the miller and the baker were brought up on charges of involuntary homicide. Still, that didn't stop rumors from circulating that the whole thing had been a CIA experiment involving LSD, and it's a story that still pops up on occasion.

You might be prescribed some

Ergot might sound like the last thing anyone would want to put into their body, but it actually does have medicinal uses — and in some countries, it might be prescribed for a few different things.

The Mayo Clinic says that the brand name drug Cafergot is one of the ergot alkaloids in this notorious family, and also says that it's prescribed to people who suffer from severe migraines. Given that it comes with a whole list of drugs it interacts with — and side effects like panic attacks, high blood pressure, and agoraphobia — it's not entirely surprising that the European Medicines Agency says that the EU suspended the use and sale of ergot-based medications that were prescribed strictly for migraines, as well as those that had been used to treat things like circulatory disorders.

That's not all it's been used for, though. According to Paul L. Schiff, PhD., both synthetic and naturally-occurring versions of the compound have been used in medications prescribed for age-related dementia, Parkinson's disease, and to prevent hemorrhaging after childbirth.